Challenge-Based vs. Traditional Biomedical Education: Analyzing Student Learning Outcomes for Enhanced Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of challenge-based learning (CBL) versus traditional instruction in biomedical education, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Challenge-Based vs. Traditional Biomedical Education: Analyzing Student Learning Outcomes for Enhanced Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of challenge-based learning (CBL) versus traditional instruction in biomedical education, targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores foundational theories, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and comparative validations to assess impacts on critical thinking, problem-solving, and real-world readiness, drawing on current research and empirical evidence.

Foundations of Challenge-Based and Traditional Biomedical Learning: Theory and Evolution

Defining Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) and Traditional Pedagogical Approaches

In the evolving landscape of biomedical education, Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) has emerged as a significant pedagogical innovation, contrasting sharply with Traditional Teaching Methods. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of their performance, focusing on experimental outcomes relevant to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Conceptual Frameworks and Key Distinctions

What is Challenge-Based Learning (CBL)?

CBL is an experiential, student-centered approach where learners collaborate to address complex, real-world problems. It emphasizes the development of competencies through a structured process of engaging with, investigating, and acting upon a relevant challenge [1] [2]. In biomedical contexts, this often mirrors real-life clinical or research scenarios.

What are Traditional Pedagogical Approaches?

Traditional methods, often termed Teacher-Centered Instruction, primarily rely on didactic lectures where students passively receive knowledge. Learning is typically structured around content delivery, with assessment focused on examinations that test recall and understanding of discrete facts [3] [4].

The core difference lies in the learning model: CBL prioritizes competency development and application through real-world problem-solving, while traditional methods focus on content acquisition and knowledge transfer [5] [2].

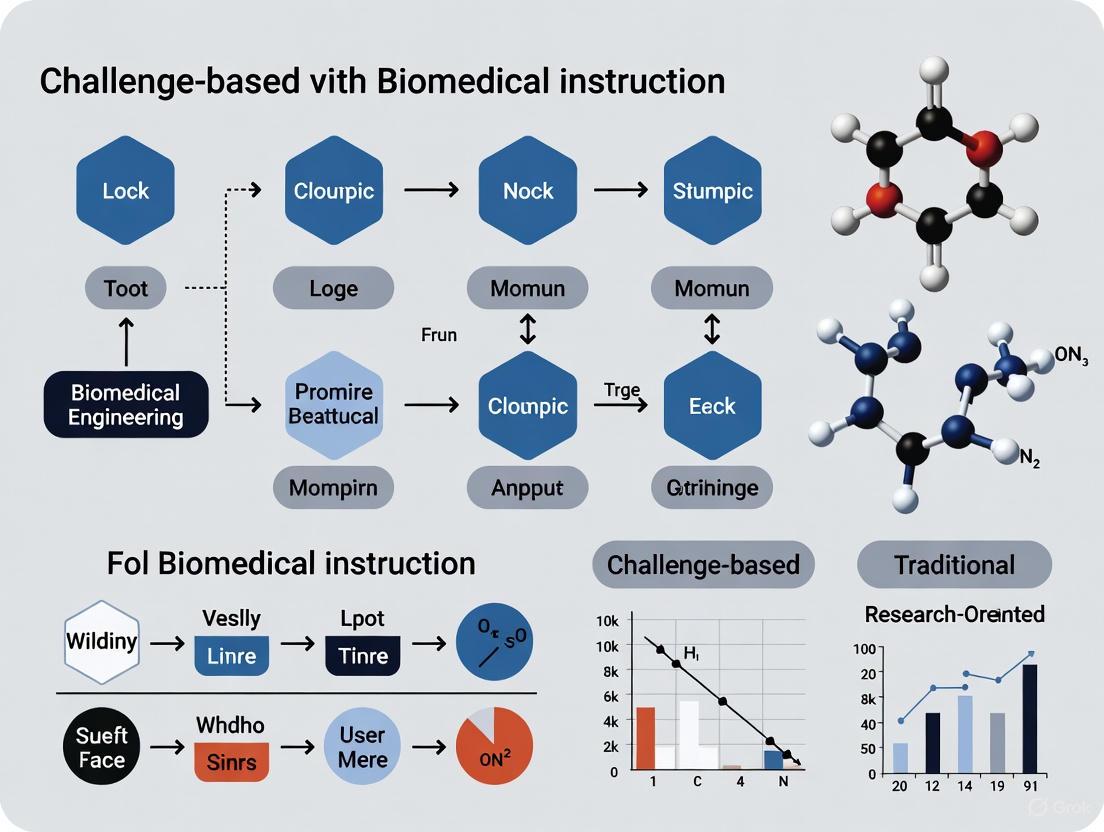

Figure 1: Comparative Workflow of Traditional versus CBL Pedagogical Approaches

Comparative Experimental Data on Educational Outcomes

Quantitative Academic Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key experimental findings comparing CBL and traditional methods across multiple disciplines in higher education.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Academic Outcomes in CBL vs. Traditional Pedagogy

| Study Focus & Population | Experimental Design | Key Outcome Measures | CBL Performance | Traditional Method Performance | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineering Physics (1,705 students) [5] | Quasi-experimental, 7 semesters | Final course grades | Improved by 9.4% | Baseline | Significant |

| ECG Interpretation (Medical Students) [6] | Prospective interventional | Post-test scores (MCQ) | Higher scores | Lower scores | p < 0.05 |

| Retention test scores | Higher retention | Lower retention | Significant | ||

| Critical Thinking (Nursing Students) [3] | Descriptive design (n=28) | CCTST Total Mean Score | 27.39/34 | Not reported | N/A |

| Analysis sub-scale | Significant improvement | p = 0.016 | |||

| Evaluation sub-scale | Significant improvement | p = 0.007 | |||

| Oncology Postgraduates (n=80) [4] | Randomized controlled trial | Examination performance | Significantly better | Lower performance | Significant |

| Problem-solving ability | High satisfaction | Lower satisfaction | Significant |

Competency and Skill Development

Beyond academic grades, CBL demonstrates significant advantages in developing essential competencies for biomedical professionals:

Critical Thinking Skills: Nursing students exposed to CBL showed significantly improved scores in analysis (p=0.016), evaluation (p=0.007), and deductive reasoning (p=0.025) on the California Critical Thinking Skills Test [3].

Problem-Solving Ability: In medical oncology education, postgraduate students in CBL groups demonstrated significantly enhanced problem-solving capabilities compared to traditional lecture-based groups [4].

Motivational Factors: In sports science education, students in CBL conditions exhibited higher competence satisfaction and lower competence frustration compared to traditional teaching groups [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To examine the impact of CBL on critical thinking in clinical decision-making among student nurses.

Population: 28 fourth-year nursing students at Kampala International University.

Intervention:

- CBL pedagogy implemented using Framework for Teaching (FFT)

- Focused on "Anemia in Pregnancy" as core clinical case

- Single 3-hour CBL session featuring:

- Progressive case disclosure mimicking real-life scenarios

- Small group work with facilitated discussion

- Teacher as facilitator with probing questions

Assessment:

- California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) questionnaire

- 34-point scale measuring analysis, evaluation, inference, deductive and inductive reasoning

- Data analyzed using percentages, descriptive statistics, and ANOVA

Key Finding: CBL produced statistically significant improvements in analysis, evaluation, and deductive reasoning sub-scales.

Objective: To measure effectiveness of CBL versus previous learning (PL) model in engineering education.

Design: Quasi-experimental study spanning seven semesters (Spring 2018 to Spring 2021).

Population: 1,705 freshman engineering students (57% in CBL, 43% in PL model).

CBL Implementation:

- Emphasis on developing disciplinary and transversal competencies

- Explicit integration of physics, math, and computing concepts

- Solution of real-life challenges through collaborative work

Assessment Metrics:

- Final exam grades

- Challenge/project report grades

- Final course grades

- Student perception surveys (n=570)

Key Finding: Overall student performance improved by 9.4% in CBL model compared to PL model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Assessment Tools and Technologies for Educational Research

| Tool/Technology | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) | Standardized assessment of critical thinking skills | Measuring analytical and evaluative reasoning in nursing students [3] |

| BioDigital Human/Complete Anatomy | 3D anatomy visualization software | Enhancing anatomy education in technology-enhanced CBL [8] |

| Generative AI Virtual Patient Platform | Simulated patient interactions for clinical practice | History-taking and communication skills development [8] |

| Immersive Learning Suite | Projection-based environment for simulated scenarios | Emergency medical simulation training [8] |

| Five-Point Likert Scale Feedback | Quantitative measurement of student perceptions | Comparing student satisfaction between CBL and traditional methods [6] |

| 20-O-Demethyl-AP3 | 20-O-Demethyl-AP3, CAS:23052-80-4, MF:C3H8NO5P, MW:169.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sc-43 | Sc-43, CAS:1400989-25-4, MF:C21H13ClF3N3O2, MW:431.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Figure 2: CBL Implementation Framework Showing Key Technological and Assessment Components

Discussion and Implications for Biomedical Education

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that CBL enhances critical thinking, problem-solving abilities, and knowledge retention compared to traditional methods. For biomedical researchers and drug development professionals, these findings suggest that CBL approaches may better prepare students for the complex, interdisciplinary challenges they will face in research and clinical practice.

The 9.4% improvement in academic performance observed in engineering education [5], coupled with significant gains in critical thinking skills in nursing education [3], provides compelling evidence for the efficacy of CBL in STEM and biomedical domains. Furthermore, the higher retention of complex concepts like ECG interpretation [6] indicates that CBL fosters deeper learning that persists beyond immediate assessment.

The successful integration of CBL in diverse educational contexts—from Mexican engineering programs [5] [2] to Ugandan nursing education [3] and Indian medical training [6]—suggests its applicability across institutional and cultural boundaries. This is particularly relevant for global drug development teams requiring standardized competencies across international research sites.

For implementation, the three-phase CBL framework (Engage, Investigate, Act) [1] provides a structured yet flexible approach that can be adapted to various biomedical contexts, from clinical case discussions to research methodology training. The role of the educator shifts from knowledge transmitter to facilitator, guiding students through complex problem-solving processes that mirror real-world scientific challenges.

The evolution of biomedical education demands sophisticated pedagogical approaches grounded in established learning theories. Among these, constructivism and behaviorism represent two fundamentally different perspectives on how students acquire knowledge and develop professional competencies. Behaviorism, with its focus on observable behaviors and environmental stimuli, provides a framework for mastering procedural tasks through reinforcement [9] [10]. In contrast, constructivism emphasizes active knowledge construction through experience and social interaction, positioning learners as active creators of their understanding [11] [12]. The highly interdisciplinary nature of biomedical engineering—which blends engineering principles with biological sciences and clinical practice—creates a complex educational landscape where both theoretical approaches find relevant applications [13]. This article examines the roles of these frameworks within biomedical education, with particular attention to their manifestation in challenge-based and traditional instructional models, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for curricular design.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Principles and Characteristics

Behaviorism: Focusing on Observable Outcomes

Behaviorism operates on the principle that learning results in a measurable change in behavior driven by environmental stimuli rather than internal mental processes [9] [10]. This theoretical approach utilizes techniques such as reward systems, repetition, feedback, and reinforcement to shape desired behaviors through conditioning [9]. In biomedical education, behaviorism proves particularly valuable when mastering specific clinical skills or procedures where correct performance can be clearly defined and measured [9]. The teacher's role in behaviorism is central—they structure the learning environment, demonstrate desired behaviors, and provide systematic reinforcement to strengthen correct responses [9]. This approach emphasizes mastery of prerequisite steps before progressing to subsequent skills, building competency in incremental stages [9].

Constructivism: Emphasizing Active Knowledge Construction

Constructivism posits that learners actively construct knowledge and meaning through their experiences and reflections, building upon existing cognitive structures [11] [14] [12]. This theory encompasses several variants, including cognitive constructivism (focusing on individual knowledge construction) and social constructivism (emphasizing knowledge building through social interaction and collaboration) [12] [15]. The core principles of constructivism include the understanding that knowledge is personally and socially constructed rather than passively absorbed, learning is an active process requiring engagement, and motivation drives learning by connecting new information to existing understanding [12]. In constructivist classrooms, teachers act as facilitators who guide discovery and create environments where students can develop their understanding through experimentation, collaboration, and problem-solving [9] [12].

Comparative Theoretical Framework

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Behaviorism and Constructivism

| Aspect | Behaviorism | Constructivism |

|---|---|---|

| View of Knowledge | External truth to be acquired | Internally constructed through experience |

| Learning Process | Passive response to environmental stimuli | Active construction and discovery |

| Teacher's Role | Director who transmits knowledge | Facilitator who guides discovery |

| Student's Role | Passive recipient of information | Active creator of knowledge |

| Assessment Focus | Observable behaviors and correct responses | Understanding processes and conceptual development |

| Typical Strategies | Drill and practice, demonstration, structured feedback | Problem-based learning, collaborative projects, inquiry |

| Primary Contributors | Watson, Skinner [14] | Piaget, Vygotsky [14] [12] |

Experimental Evidence: Comparing Learning Outcomes

Research in biomedical education contexts provides empirical evidence for the applications and outcomes associated with behaviorist and constructivist approaches. These frameworks manifest differently across various instructional models, particularly when comparing traditional and challenge-based learning environments.

Behaviorism in Traditional Biomedical Instruction

Traditional biomedical education often incorporates behaviorist principles through structured skill development and direct instruction. In clinical skills courses, behaviorism proves appropriate as "correct responses in performing skills can be learnt slowly over time as students are being provided feedback, rewards and encouragement by teachers" [9]. These environments utilize checklists, rating forms, and direct observation to assess performance and provide reinforcement [9]. A qualitative study on medical classroom behavior found that the learning environment—including teacher approaches and educational content—significantly influences student behaviors and academic progress, highlighting the behaviorist concern with environmental impact on observable outcomes [10].

Constructivism in Challenge-Based Learning Environments

Challenge-based learning (CBL) represents a robust application of constructivist principles in biomedical education. CBL engages students in collaborative problem-solving of real-world challenges, requiring them to design, prototype, and test solutions [16]. This approach emphasizes purposeful learning-by-doing in contrast to passive absorption of information [16]. Implementation of CBL in a bioinstrumentation course at Tecnologico de Monterrey demonstrated that students "strongly agreed that this course challenged them to learn new concepts and develop new skills" despite the substantial time investment required from educators [16]. Another study noted that CBL provides a platform for "situated learning experience doing real things," which increases student engagement and learning effectiveness [16].

The NICE (New frontier, Integrity, Critical and creative thinking, Engagement) strategy in biomedical engineering education exemplifies constructivist principles through its case-based approach and industry engagement [13]. This strategy employs active learning methods including research article analysis using AI tools, case studies of scientific integrity, and industry-sponsored projects [13]. These constructivist approaches resulted in improved student understanding of emerging technologies, enhanced critical thinking skills, and better preparation for practical product development processes [13].

Comparative Learning Outcomes

Table 2: Learning Outcomes in Behaviorist vs. Constructivist Approaches

| Outcome Category | Behaviorist Approaches | Constructivist Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Skill Acquisition | Mastery of prerequisite steps before moving to subsequent skills [9] | Development of integrated skill sets through project work [16] |

| Knowledge Retention | Remembering and reproducing information [11] | Deep understanding through application and connection to real-world contexts [12] |

| Critical Thinking | Following prescribed procedures and protocols [9] | Analyzing complex problems and generating novel solutions [13] |

| Professional Identity | Adopting standardized professional behaviors [10] | Developing personal understanding of professional roles through experience [15] |

| Student Engagement | Compliance with instructional requirements [9] | High intrinsic motivation through relevance and autonomy [16] [12] |

| Assessment Metrics | Observable performance against standardized criteria [9] | Diverse products and processes demonstrating understanding [16] |

Methodological Approaches: Experimental Protocols in Educational Research

Protocol for Challenge-Based Learning Implementation

The implementation of challenge-based learning in biomedical education follows a structured protocol that reflects constructivist principles. In a study conducted at Tecnologico de Monterrey, researchers implemented CBL in a third-year bioinstrumentation course with thirty-nine students divided into fourteen teams [16]. The experimental protocol included:

- Challenge Design: Students were challenged to "design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy" in collaboration with an industry partner [16].

- Blended Learning Activities: The course combined online communication, lab experiments, and in-person CBL activities [16].

- Team-Based Approach: Student teams worked collaboratively through the entire problem-solving process, from initial research to prototype development [16].

- Assessment Method: Researchers used an institutional student opinion survey to assess the implementation success, measuring perceptions of new learning, skill development, and student-lecturer interaction [16].

This protocol resulted in positive student feedback despite increased planning and tutoring requirements, demonstrating the resource-intensive nature of constructivist approaches [16].

Protocol for Behaviorist Skill Development

Research on behaviorist approaches in medical education often follows experimental protocols focused on measurable skill acquisition:

- Structured Skill Sequencing: Complex procedures are broken down into discrete, sequential steps mastered through repetition [9].

- Immediate Feedback: Correct performance is reinforced through immediate feedback from instructors or through structured assessment tools like checklists [9].

- Environmental Manipulation: Learning environments are carefully controlled to eliminate distractions and provide optimal conditions for skill practice [10].

- Standardized Assessment: Observable behaviors are evaluated against predetermined criteria to ensure competency before progression [9].

These protocols emphasize external shaping of behavior through environmental design and systematic reinforcement, contrasting with the internal construction of knowledge emphasized in constructivist approaches.

Qualitative Research on Clinical Clerkships

A study on clinical clerkships employed qualitative methods based on social constructivism to understand the "black box" of clinical learning [15]. The research protocol included:

- Participant Selection: Eight sixth-year medical students who had completed a two-year rotation-based clerkship were selected through purposive sampling [15].

- Data Collection: Researchers conducted semi-structured, in-depth individual interviews averaging 90 minutes, supplemented by reflective journals and institutional documents [15].

- Theoretical Framework: Data analysis was guided by Lave and Wenger's situated learning theory and Wenger's social theory of learning, focusing on professional identity formation through participation and reification [15].

- Data Analysis: Interview transcripts were analyzed to identify emerging themes related to identity development and learning processes in clinical settings [15].

This approach revealed that students developed different aspects of their professional identities through negotiation of meaning in clinical environments, highlighting the complex social learning processes that constructivism helps illuminate [15].

Visualizing the Conceptual Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the key processes and relationships in constructivist and behaviorist learning approaches within biomedical education:

Constructivism and Behaviorism Learning Processes

This diagram illustrates the sequential processes in both theoretical frameworks and their integration in biomedical education. The behaviorism cycle (blue) shows the stimulus-response-reinforcement pattern leading to changed behavior, while the constructivism cycle (green) demonstrates the experiential learning process leading to constructed knowledge. Both ultimately contribute to comprehensive biomedical education (yellow).

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Educational Experiments

| Resource/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AI Literature Search Tools (e.g., ChatGPT, DeepSeek) | Assist students in literature search and concept clarification in CBL | Used in NICE strategy to help students understand cutting-edge research [13] |

| Structured Assessment Rubrics | Provide objective criteria for evaluating skill performance | Behaviorist assessment of clinical skills using checklists and rating forms [9] |

| Case Studies (positive and negative examples) | Illustrate ethical principles and professional standards | Analysis of Theranos fraud case to teach research integrity [13] |

| Industry Partnership Frameworks | Connect academic learning with real-world applications | Company-provided objectives for student design projects [13] |

| Semi-Structured Interview Protocols | Collect qualitative data on student learning experiences | Understanding clinical clerkship experiences from student perspective [15] |

| Reflective Journals/Portfolios | Document learning processes and identity formation | Tracking professional development in clinical settings [15] |

| Project-Based Learning Kits | Provide materials for prototype development and testing | Bioinstrumentation projects creating cardiac gating devices [16] |

Discussion: Implications for Biomedical Education Research

The comparative analysis of constructivism and behaviorism reveals distinct yet potentially complementary roles in biomedical education. Behaviorist approaches provide structured methodologies for mastering foundational skills and procedures essential to biomedical practice, particularly in technical and clinical domains where precision and standardization are critical [9] [10]. Constructivist approaches, particularly through challenge-based learning models, foster adaptive expertise, critical thinking, and innovation capabilities necessary for addressing novel problems in rapidly evolving biomedical fields [16] [13].

The integration of both theoretical frameworks may offer the most comprehensive approach to biomedical education. Foundational knowledge and skills can be efficiently developed through behaviorist-influenced methods, while higher-order competencies and professional identity formation benefit from constructivist approaches [11] [17]. This balanced perspective acknowledges that different learning outcomes require different instructional strategies, with behaviorism excelling in developing technical proficiency and constructivism fostering innovation and adaptive problem-solving.

Future research should explore optimal integration of these frameworks across the biomedical education continuum, from undergraduate training through professional development. Particular attention should be given to longitudinal studies comparing long-term outcomes of graduates from different instructional approaches, especially their performance in research and drug development contexts where both technical precision and creative problem-solving are essential.

Historical Context and Evolution of Instructional Methods in Biomedicine

The landscape of biomedical education has undergone significant transformation, evolving from traditional, lecture-based formats towards innovative, student-centered pedagogical models. This shift is driven by the need to prepare healthcare professionals and biomedical engineers who can navigate complex, real-world challenges and innovate in dynamic work environments [18] [19]. Among these innovative approaches, Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) has emerged as a prominent method, emphasizing the practical application of knowledge to solve authentic problems. This guide provides a objective comparison of student learning outcomes in challenge-based versus traditional instructional methods within biomedical education, supported by experimental data and detailed methodological protocols.

Historical Context of Biomedical Education

The evolution of biomedical education is marked by a continual adaptation to scientific advancement and societal needs.

- Early Foundations: Modern biomedical education traces its roots to the post-World War II era, which saw the convergence of biological experimentation and medical practice, creating the foundational "biomedical complexes" characterized by intensified life sciences research and a hunt for novel therapeutic molecules [18].

- Traditional Paradigm: For much of the twentieth century, medical education followed a two-pillar model established by the Flexner Report (1910), separating foundational basic sciences in pre-clinical years from clinical sciences training in later years [20]. This teacher-centered, lecture-based approach prioritized the transmission of established scientific knowledge.

- Shift to Integration and Competency: Recent decades have witnessed a paradigm shift towards integrated, competency-based curricula [20]. This movement aims to produce physicians and engineers "fit for the twenty-first century" by blending basic science with clinical application and emphasizing the demonstration of competencies over mere knowledge acquisition [20].

- Rise of Active Learning: This shift has facilitated the adoption of active learning strategies like CBL, which positions students as active participants in their learning journey, collaboratively developing solutions to real-world problems [21].

Comparative Analysis: Challenge-Based vs. Traditional Learning

Experimental studies directly comparing these pedagogical approaches reveal distinct patterns in learning outcomes and skill development.

Key Comparative Studies and Outcomes

The table below summarizes quantitative findings from pivotal studies comparing student performance in CBL and traditional instructional settings.

Table 1: Summary of Key Comparative Studies on CBL vs. Traditional Instruction

| Study Focus | Study Design & Participants | Knowledge Gains (Traditional vs. CBL) | Innovative Thinking & Problem-Solving | Overall Performance & Perception |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Engineering (Biotransport) [22] [23] | Comparative study; intervention group taught with HPL-based CBL, control with traditional lectures. | Equivalent gains between HPL (CBL) and traditional students [22] [23]. | HPL (CBL) students showed significantly greater improvement in innovative problem-solving abilities [22] [23]. | Not specified in available excerpts. |

| Engineering Education (Physics) [5] | Quasi-experimental study; 1,705 freshman engineering students over seven semesters. | Final exam grades were one measure among others. | Challenge grades in CBL were similar to project grades in the traditional model. | Final course grades improved by 9.4% in the CBL model. 71% of students had a favorable perception of CBL for competency development [5]. |

| Bioinstrumentation Course [16] | Implementation case study; 39 students in a blended CBL course. | Students reported being challenged to learn new concepts. | Students reported developing new skills through the CBL experience. | Students rated their learning experience and student-lecturer interaction positively, despite increased planning time for instructors [16]. |

Synthesis of Comparative Findings

The data indicates a consistent trend: while traditional instruction remains effective for the transfer of core disciplinary knowledge, CBL offers a significant advantage in fostering higher-order cognitive skills.

- Knowledge Acquisition: Students in CBL environments achieve equivalent knowledge gains to their peers in traditional courses, as demonstrated by pre/post-test results and final exam performance [22] [23] [5].

- Innovative Problem-Solving: CBL students consistently demonstrate superior abilities in innovative thinking and adapting knowledge to novel contexts [22] [23]. This aligns with the development of "adaptive expertise," a key goal of modern engineering and medical education [22].

- Student Engagement and Performance: Large-scale studies show that CBL can lead to improved overall academic performance, as reflected in higher final course grades, and is met with positive student perceptions regarding skill development [5].

Experimental Protocols in CBL Research

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of comparative studies, researchers adhere to structured experimental protocols.

Protocol 1: Comparative Study in a Core Biomedical Course

This protocol is modeled on the study comparing biotransport instruction [22] [23].

- Objective: To compare the efficacy of CBL (specifically, the "How People Learn" (HPL) framework) with traditional lecture-based instruction in developing subject knowledge and innovative problem-solving skills.

- Population: Undergraduate students enrolled in a core biomedical engineering course (e.g., biotransport).

- Group Allocation:

- Intervention Group: Receives instruction via the CBL/HPL method.

- Control Group: Receives instruction via traditional didactic lectures.

- Intervention (CBL/HPL Method): The learning environment is designed to be learner-centered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered, and community-centered. Instruction is built around real-world challenges that require students to engage in a full cycle of inquiry, collaboration, and solution development [22].

- Outcome Measures:

- Knowledge Test: A standardized pre-test and post-test covering core domain knowledge.

- Innovative Problem-Solving Assessment: A pre-test and post-test featuring novel, non-routine problems to assess adaptive expertise.

- Data Analysis: Comparison of normalized learning gains on both the knowledge and innovation assessments between the intervention and control groups using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests).

Protocol 2: Quasi-Experimental Implementation at Program Level

This protocol is based on the institutional study of the Tec21 model [5].

- Objective: To assess the impact of a large-scale, competency-based CBL model on student academic performance and perceptions.

- Population: A large cohort of freshman engineering students (e.g., n=1705) over multiple semesters.

- Group Allocation:

- CBL Cohort: Students enrolled after the implementation of the CBL model.

- Traditional (PL) Cohort: Students enrolled under the previous traditional learning model.

- Intervention (CBL Model): The curriculum is restructured around real-life challenges crafted in conjunction with industrial partners. Students work collaboratively to research and develop solutions, integrating academic content from multiple disciplines (e.g., physics, math, computing) [5].

- Outcome Measures:

- Academic Performance: Final exam grades, challenge/project report grades, and final course grades.

- Student Perception: Standardized opinion surveys measuring students' views on competency development and problem-solving skills.

- Data Analysis: Statistical comparison of average grades between cohorts and thematic analysis of survey responses.

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the structural differences and key stages of these two pedagogical approaches.

Diagram 1: Comparison of Instructional Workflows. This diagram contrasts the linear, content-focused path of Traditional Instruction with the iterative, inquiry-driven cycles of Challenge-Based Learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for CBL Experiments

Implementing and studying CBL requires specific "research reagents" – the conceptual tools and frameworks that ensure rigorous educational design and evaluation.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CBL Implementation and Research

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function in CBL Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| HPL Framework [22] | Theoretical Framework | Guides the design of learning environments to be learner-centered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered, and community-centered. |

| Real-World Challenge [16] [5] | Core Intervention | Serves as the central, authentic problem that drives student inquiry, collaboration, and solution development. |

| Industry/Clinical Training Partner [16] [5] | Contextual Resource | Provides real-world relevance, formalizes the challenge, and offers expert feedback on proposed solutions. |

| Adaptive Expertise Assessment [22] | Evaluation Tool | Measures the ability to apply knowledge innovatively in novel contexts, a key outcome of CBL. |

| Competency Rubrics [5] | Evaluation Tool | Provides structured criteria for assessing the development of both disciplinary and transversal competencies (e.g., collaboration, critical thinking). |

| Structured Reflection Prompts [19] | Metacognitive Tool | Facilitates student self-assessment and consolidation of learning throughout the challenge process. |

| BMVC | BMVC Reagent | BMVC is a research-use only (RUO) fluorescent probe for studying DNA G-quadruplex structures and developing photodynamic therapy (PDT) applications. |

| SQDG | SQDG Sulfoquinovosyl Diacylglycerol |

The comparative analysis between challenge-based and traditional instruction in biomedicine reveals a nuanced picture. Traditional methods demonstrate enduring effectiveness in facilitating the acquisition of core knowledge. However, the evidence strongly indicates that Challenge-Based Learning equips students with a critical complementary skill set. CBL significantly enhances innovative problem-solving abilities, adaptive expertise, and student engagement, producing equivalent content knowledge gains while better preparing researchers, scientists, and biomedical professionals for the complex, unpredictable challenges of the modern workplace. The choice of instructional method, therefore, should be guided by the specific learning objectives, with CBL representing a powerful evidence-based approach for fostering the innovators and agile problem-solvers required in contemporary biomedicine.

Key Differences in Learning Objectives and Student Engagement Strategies

Biomedical education has undergone significant transformation in recent decades, moving from traditional, instructor-centered approaches toward innovative, student-centered methodologies. This shift is particularly evident in the comparison between challenge-based learning (CBL) and traditional didactic instruction. As biomedical fields evolve at an unprecedented pace, educators face increasing pressure to develop instructional strategies that not only convey essential knowledge but also cultivate the adaptive problem-solving capabilities required for professional success. This comprehensive analysis examines key differences in learning objectives and engagement strategies between these two educational approaches, drawing on empirical evidence from biomedical engineering and medical education contexts. The framework for understanding these distinctions lies in their fundamental educational philosophies: traditional methods prioritize knowledge transmission and content mastery, while challenge-based approaches emphasize knowledge application and adaptive expertise development [22] [24] [23].

Research indicates that the choice between these instructional paradigms has significant implications for student outcomes. While traditional instruction has demonstrated effectiveness in building foundational knowledge, challenge-based approaches appear to offer distinct advantages in developing higher-order thinking skills and professional competencies. This article systematically compares these models across multiple dimensions, including learning objectives, engagement strategies, assessment outcomes, and implementation requirements, providing educators and curriculum designers with evidence-based insights to inform pedagogical decisions [25] [22] [16].

Comparative Analysis of Learning Objectives

Foundational Philosophies and Goal Structures

The learning objectives in traditional versus challenge-based biomedical instruction reflect fundamentally different conceptions of what constitutes valuable learning. Traditional didactic instruction typically emphasizes the systematic acquisition of disciplinary knowledge through structured content delivery, with learning objectives often focusing on content coverage, factual recall, and procedural application within well-defined parameters. In contrast, challenge-based learning frames objectives around authentic problems drawn from professional practice, emphasizing the development of adaptive expertise that enables students to transfer knowledge to novel situations [22] [24].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Learning Objectives

| Objective Category | Traditional Instruction | Challenge-Based Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Focus | Content mastery within defined curriculum | Knowledge integration across disciplines |

| Skill Development | Procedural competence in standard methods | Innovative problem-solving in novel contexts |

| Thinking Processes | Analytical thinking within established frameworks | Adaptive and generative thinking abilities |

| Professional Preparation | Foundation for further specialized training | Readiness for complex professional environments |

Knowledge Types and Cognitive Processes

The taxonomy of learning objectives differs substantially between approaches. Traditional instruction often prioritizes declarative knowledge (knowing what) and procedural knowledge (knowing how) within established disciplinary boundaries. Assessments typically measure students' abilities to reproduce and apply this knowledge in structured formats. Conversely, challenge-based learning targets conditional knowledge (knowing when and why) and strategic knowledge (knowing how to learn), with objectives focused on students' capacities to navigate ambiguous problems, make strategic decisions about solution approaches, and monitor their own learning processes [22] [23].

Research by Martin et al. demonstrated that while both instructional approaches produced equivalent gains in foundational knowledge, challenge-based instruction led to significantly greater development of innovative thinking abilities. Students in the challenge-based condition demonstrated superior performance when transferring their knowledge to novel problem contexts, suggesting that this approach more effectively develops the adaptive expertise required for professional innovation [22] [23].

Student Engagement Strategies

Structural Frameworks for Engagement

Engagement strategies in traditional biomedical education typically center on structured participation mechanisms such as in-class questions, scheduled discussions, and assigned homework. These strategies operate within a predictable framework where instructors maintain primary control over the learning process. In contrast, challenge-based learning employs authentic problem contexts to create intrinsic motivation, positioning students as active agents in their learning process. The CBL framework typically includes: engaging with a big idea relevant to professional practice, formulating essential questions, addressing a concrete challenge, developing and implementing solution strategies, and sharing results with authentic audiences [24] [16].

Table 2: Engagement Strategy Comparison

| Engagement Dimension | Traditional Instruction | Challenge-Based Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Motivational Source | Extrinsic (grades, requirements) | Intrinsic (problem relevance, autonomy) |

| Student Role | Knowledge recipient | Active problem-solver and co-creator |

| Instructor Role | Primary knowledge source | Facilitator and guide |

| Social Structure | Individual achievement focus | Collaborative team-based work |

| Feedback Mechanisms | Structured and scheduled | Continuous through iteration |

Implementation and Impact of Engagement Strategies

Empirical studies demonstrate that the engagement strategies employed in challenge-based learning environments lead to measurable differences in student behaviors and attitudes. Research examining CBL implementations in bioinstrumentation courses reported significantly higher levels of cognitive engagement, collaborative integration, and persistence in problem-solving compared to traditional formats [16]. These engagement patterns correlate with the development of professional competencies including self-directed learning capabilities, collaborative skills, and creative confidence [24] [16].

Blended learning approaches that combine digital platforms with flipped classroom models have shown particular promise for enhancing engagement in biomedical education. Studies comparing blended and traditional formats found significantly higher learning satisfaction and more positive self-evaluations among students in blended environments that incorporated challenge-based elements. These findings suggest that strategic technology integration can amplify the engagement benefits of challenge-based approaches [25].

Experimental Evidence and Outcome Data

Comparative Studies in Biomedical Education

Rigorous comparative studies provide compelling evidence regarding the differential impacts of traditional and challenge-based instructional approaches. A 2007 study published in Annals of Biomedical Engineering directly compared student learning in challenge-based and traditional biotransport courses [22] [23]. This research employed a controlled design with pre- and post-testing to measure knowledge acquisition and innovative thinking abilities. The results demonstrated equivalent knowledge gains between groups but significantly greater improvement in innovative problem-solving among students in the challenge-based condition [22] [23].

More recent research examining blended learning in evidence-based medicine education found that students in the experimental (blended challenge-based) group showed significantly greater improvement from pre-test to post-test compared to the traditional group (score increases of 4.05 vs. 2.00 points) [25]. These students also reported substantially higher learning satisfaction and more positive self-evaluations of their learning outcomes [25].

Meta-Analytic Evidence

Broad-scale analyses of active learning approaches provide additional evidence for the effectiveness of challenge-based pedagogies. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis examined self-directed learning (a key component of challenge-based approaches) versus traditional didactic learning in undergraduate medical education [26]. The analysis included 14 studies with 1,792 students and found that self-directed learning approaches significantly outperformed traditional methods on exam scores (overall mean difference = 2.399, 95% CI [0.121-4.678]) [26].

Similarly, a 2025 meta-analysis of problem-based learning combined with seminar teaching (a close relative of challenge-based learning) demonstrated superior outcomes across multiple domains including theoretical knowledge, clinical skills, case analysis ability, and learning interest compared to traditional instruction [27]. These findings suggest that the benefits of challenge-based approaches extend beyond specific contexts to broader educational applications.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes from Comparative Studies

| Study | Knowledge Gains | Problem-Solving Improvements | Engagement Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Martin et al. (2007) [22] [23] | Equivalent to traditional | Significantly greater than traditional | Not reported |

| Blended EBM Study (2024) [25] | Greater improvement (4.05 vs. 2.00) | Not assessed | Significantly higher satisfaction |

| SDL Meta-Analysis (2024) [26] | Superior to traditional (MD = 2.399) | Not separately assessed | Not quantitatively synthesized |

| PBL+Seminar Meta-Analysis (2025) [27] | Significantly higher (MD = 4.99) | Case analysis significantly better | Learning interest significantly higher |

Methodological Approaches in Key Studies

Experimental Designs and Implementation Models

The evidence base comparing challenge-based and traditional instruction in biomedical education incorporates diverse methodological approaches. A representative example comes from a 2024 study implementing CBL in a bioinstrumentation course [16]. This implementation followed a structured framework: students worked in teams to tackle authentic challenges (designing respiratory or cardiac gating devices for radiotherapy), engaged in blended learning activities combining online and in-person work, and collaborated with industry partners to ensure real-world relevance [16].

Another rigorous comparison in evidence-based medicine education employed a cohort design with careful controls [25]. The traditional learning group received lecture-based instruction with in-class question sessions, while the blended challenge-based group engaged with pre-class materials, developed debriefing slides in subgroups, and participated in instructor-facilitated synthesis sessions [25]. This methodology allowed direct comparison of knowledge acquisition while also capturing differences in engagement and satisfaction.

Assessment Strategies and Outcome Measures

Research in this domain has employed diverse assessment strategies to capture the multidimensional impacts of different instructional approaches. The Martin et al. study utilized a novel assessment framework that separately measured knowledge acquisition (through standard content tests) and innovative thinking (through transfer problems requiring adaptation to novel contexts) [22] [23]. This approach revealed the distinctive advantage of challenge-based learning in developing adaptive capacities beyond content mastery.

Other studies have incorporated comprehensive evaluation matrices including quantitative metrics (test scores, skill assessments), self-report measures (satisfaction, self-efficacy, engagement surveys), and behavioral observations (participation patterns, collaboration quality) [25] [16]. This multidimensional assessment approach provides a more complete picture of how different instructional strategies influence the student learning experience.

Decision Framework for Biomedical Instructional Strategies

Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Implementing rigorous comparisons between instructional approaches requires specific "research reagents" – the conceptual and methodological tools needed to design, implement, and assess educational interventions.

Table 4: Essential Research Methodologies for Educational Comparisons

| Method Category | Specific Tools | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Designs | Controlled cohort studies | Comparing outcomes between instructional conditions [25] |

| Pre-post testing with transfer assessments | Measuring knowledge gains and adaptive expertise [22] [23] | |

| Assessment Instruments | Content knowledge tests | Quantifying foundational knowledge acquisition [25] [26] |

| Innovative problem-solving measures | Assessing application and adaptation capabilities [22] [23] | |

| Engagement and satisfaction surveys | Capturing student experiences and perceptions [25] [16] | |

| Implementation Frameworks | CBL structured protocols | Ensuring consistent challenge-based implementation [24] [16] |

| Blended learning models | Combining digital and in-person learning elements [25] | |

| Analysis Approaches | Meta-analytic synthesis | Aggregating findings across multiple studies [26] [27] |

| Multivariate statistical methods | Accounting for confounding variables and interactions |

These methodological tools enable rigorous investigation of the complex relationships between instructional strategies and learning outcomes. Their appropriate application requires specialized knowledge in both biomedical content and educational research methods.

The comparative analysis of challenge-based and traditional instructional approaches in biomedical education reveals distinct profiles of strengths and limitations. Traditional didactic methods demonstrate effectiveness in building foundational knowledge efficiently and predictably, making them appropriate for content-heavy foundational courses. Conversely, challenge-based approaches excel at developing adaptive expertise, innovative problem-solving capabilities, and professional competencies that transfer to novel situations [22] [24] [23].

The emerging evidence suggests that strategic integration of both approaches may offer the most powerful educational pathway. Blended models that combine the structured knowledge building of traditional methods with the authentic application focus of challenge-based learning demonstrate particular promise [25] [16]. Future research should explore optimal sequencing and integration of these approaches across biomedical curricula, with attention to longitudinal impacts on professional success and adaptive capacity in evolving biomedical fields.

For educational researchers and curriculum designers, these findings highlight the importance of aligning instructional strategies with specific learning objectives. When the goal is efficient knowledge transmission within established paradigms, traditional methods remain effective. When the objective extends to developing innovators capable of advancing biomedical practice, challenge-based approaches offer distinct advantages that merit their increased implementation costs and logistical complexities [16]. The evolving landscape of biomedical education will likely continue to leverage both paradigms, with strategic selection guided by explicit learning priorities and evidence-based practice.

Implementing Challenge-Based Learning in Biomedical Curricula: Methods and Real-World Applications

Designing Effective CBL Modules for Biomedical and Drug Development Courses

Table 1: Summary of Key Comparative Findings

| Educational Modality | Exam Performance (vs. LBL) | Skill Development | Knowledge Retention | Student Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-Based Learning (CBL) | Significantly higher (SMD = 0.58, P < 0.05) [28] | Enhanced communication, problem-solving, and clinical skills [28] | Improved retention in therapeutic drug monitoring (82.5% vs 78.1%) [29] | Higher satisfaction (RR = 1.63, P < 0.05) [28] |

| CBL with Virtual Patients | No significant difference in initial knowledge (85.5% vs 87.0%) [29] | N/A | Better calculation retention (90.3% vs 86.9%, p=0.032) [29] | N/A |

| CBL with Standardized Patients (SP) | Significantly higher (MD = 5.91, P < 0.001) [30] | Improved clinical performance (MD = 7.62, P < 0.001) [30] | N/A | Substantially higher (OR = 7.19, P < 0.001) [30] |

| Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) | Equivalent knowledge gains [31] | Significantly greater improvement in innovative thinking [31] | N/A | Increased engagement and contextual awareness [16] |

| Team-Based Learning (TBL) | Enhanced but not statistically significant (MD = 2.27) [32] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

The complex, interdisciplinary nature of modern biomedical engineering and drug development demands educational strategies that move beyond knowledge transmission to foster robust problem-solving, innovation, and clinical reasoning. Traditional, lecture-based learning (LBL) has been the cornerstone of science education for decades. However, its limitations in preparing students for real-world challenges have become increasingly apparent [30] [28]. In response, active learning modalities like Case-Based Learning (CBL) and Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) are gaining prominence. These methods immerse learners in realistic scenarios, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and professional application. This guide provides a data-driven comparison of these innovative approaches against traditional instruction, offering evidence-based protocols for designing effective educational modules for scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Perspective

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide the highest level of evidence for evaluating educational interventions. The data demonstrates a clear, positive trend for active learning strategies over traditional methods.

Case-Based Learning (CBL)

A 2025 meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in pharmacy education provided compelling evidence for CBL's effectiveness. The analysis, encompassing 1,339 students, found that CBL not only improved exam scores but also cultivated a range of essential competencies crucial for biomedical professionals [28].

Table 2: CBL Effectiveness on Skills and Satisfaction (from Meta-Analysis) [28]

| Outcome Measure | Risk Ratio (RR) or Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exam Scores | SMD = 0.58 | [0.39, 0.77] | < 0.05 |

| Communication & Collaboration Skills | RR = 2.49 | [1.17, 5.27] | < 0.05 |

| Problem-Solving Abilities | RR = 2.19 | [1.26, 3.80] | < 0.05 |

| Clinical Practice Skills | RR = 2.39 | [1.46, 3.92] | < 0.05 |

| Class Satisfaction | RR = 1.63 | [1.22, 2.18] | < 0.05 |

Integrated Methodologies: CBL with Standardized Patients

The combination of CBL with Standardized Patients (SP) creates a powerful, immersive learning environment. A 2025 meta-analysis of 31 RCTs (n=2,674) in Chinese medical education quantified the impact of this integrated approach, showing substantial improvements across all three domains of Kirkpatrick's evaluation model: reaction, learning, and behavior [30].

Table 3: Effectiveness of SP Combined with CBL (from Meta-Analysis) [30]

| Outcome Domain | Mean Difference (MD) or Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value | GRADE Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Satisfaction | OR = 7.19 | [3.80, 13.60] | < 0.001 | Moderate |

| Theoretical Knowledge | MD = 5.91 | [4.63, 7.18] | < 0.001 | Low (due to inconsistency) |

| Clinical Practice Performance | MD = 7.62 | [6.16, 9.08] | < 0.001 | Low (due to inconsistency) |

Subgroup analyses further revealed that improvements in theoretical knowledge were more pronounced among medical students, while enhancements in clinical performance were more significant among resident physicians, highlighting the value of tailoring interventions to the learner's stage of professional development [30].

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Translating educational theory into practice requires structured protocols. The following are detailed methodologies from cited studies that can be adapted for course design.

Protocol 1: Virtual Patient CBL for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

This protocol was successfully implemented in a pharmacy curriculum to teach antibiotic dosing and monitoring with reduced contact hours [29].

- Course Structure: The 2-credit course met twice weekly for one-hour sessions. The first weekly session covered conceptual material with practice cases, and the second was a dedicated case-day.

- Case Design & Platform: All practice and graded cases were built using a simulated Electronic Health Record (EHR) with virtual patients (e.g., EHR Go Platform) to mimic an inpatient Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE).

- Session Workflow:

- In-Class Practice: Students completed review and answered practice cases during course time with instructor facilitation.

- Graded Assignments: Following practice, students completed graded cases individually or in groups within 24 hours. Submissions required a pharmacokinetic consult note and calculations.

- Assessment Shift: The course grade was weighted toward application, with graded cases comprising 40% of the final grade, exams 50%, and quizzes/pre-class assignments 10%.

Virtual Patient CBL Workflow

Protocol 2: Case-Based VR Simulation for Severe Pelvic Trauma

This protocol from orthopedic surgery education integrates CBL with Virtual Reality (VR) to teach complex clinical reasoning and procedural skills for a high-stakes, low-frequency medical scenario [33].

- Case Development:

- Collaborative Design: Specialists in basic and clinical medicine design cases based on literature, real patient cases, and course syllabi.

- Scenario Progression: A representative case follows a patient from the emergency department to the intensive care unit and operating room as their condition worsens, allowing learners to acquire both declarative and procedural knowledge.

- Scripting: Detailed scripts are created for different clinical environments (emergency room, ICU, OR), specifying learner interactions with the Electronic Standardized Patient (ESP) for history taking, physical examination, and auxiliary tests.

- Framework Construction:

- A 3D pelvic fracture model is developed using tools like Maya and ZBrush, based on real clinical data.

- The VR system architecture includes multiple ports and modules to support the learning journey.

- Implementation & Evaluation:

- A comprehensive training plan is rolled out for administrators, instructors, and students.

- Learning is evaluated using a one-group pretest-posttest design, assessing knowledge, procedural skills, and confidence.

Protocol 3: Challenge-Based Learning in Biomedical Instrumentation

This protocol was implemented in a third-year biomedical engineering blended course, challenging students to design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy [16].

- The CBL Framework: The process follows a structured progression:

- Big Idea: A broad concept like improving radiotherapy safety.

- Essential Question: What is required to accurately gate radiation delivery?

- The Challenge: A concrete, actionable goal—e.g., "Design a cardiac gating device."

- Solution Development: Teams research, design, and prototype their solutions.

- Assessment & Implementation: Solutions are evaluated for connection to the challenge, technical accuracy, and potential efficacy.

- Publishing: Results and experiences are documented and shared.

- Industry Partnership: Collaboration with an industry partner ensures the challenge is authentic and provides real-world context and feedback.

- Blended Format: The experience combines online communication, lab experiments, and in-person CBL activities.

CBL Framework Progression

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Implementation

Table 4: Essential Resources for Developing CBL and CBL Modules

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Educational Design |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated EHR Platforms | EHR Go Platform [29] | Provides an authentic, risk-free environment for students to access patient data, make clinical decisions, and document care, replicating a real clinical setting. |

| Virtual Reality (VR) Systems | Custom ESP for Severe Pelvic Trauma [33] | Creates immersive, interactive simulations of complex clinical scenarios, allowing for repetitive practice of both cognitive and procedural skills without consuming physical resources. |

| AI & Active Learning Libraries | DeepChem [34] | Offers machine learning tools, including active learning algorithms, which can be used to optimize in-silico drug discovery processes and teach these advanced concepts. |

| Domain-Specific Language Models | PharmBERT [35] | A large language model pre-trained on drug labels, useful for teaching and automating the extraction of critical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic information from complex regulatory documents. |

| Structured Pedagogical Frameworks | Kirkpatrick's Four-Level Model [30] | Provides a validated structure for evaluating educational interventions from student satisfaction (Level 1) to applied learning (Level 2) and broader impacts. |

| DTP3 | DTP3, CAS:1809784-29-9, MF:C26H35N7O5, MW:525.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Methoxy-4-[(5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)-hydrazonomethyl]-phenol | 2-Methoxy-4-[(5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobenzo[4,5]thieno[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)-hydrazonomethyl]-phenol, CAS:304684-77-3, MF:C18H18N4O2S, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The collective evidence demonstrates that active learning modalities—particularly CBL, CBL, and their technology-enhanced variants—consistently match or surpass traditional lecture-based instruction in foundational knowledge acquisition while significantly outperforming it in developing critical applied skills, enhancing knowledge retention, and boosting student satisfaction and engagement. The choice of modality depends on the specific learning objectives: CBL is exceptional for teaching clinical reasoning within defined parameters, CBL fosters innovative thinking and problem-solving for open-ended challenges, and TBL promotes collaborative learning.

For researchers and educators in biomedical engineering and drug development, the implication is clear: integrating these evidence-based, active learning strategies is crucial for preparing a workforce capable of tackling the complex, interdisciplinary problems that define the future of healthcare and therapeutic innovation.

The rapid evolution of the biomedical fields demands educational approaches that equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with robust theoretical knowledge and the problem-solving skills necessary for clinical and laboratory practice. For years, lecture-based learning (LBL), a quintessential traditional teaching approach, has been widely utilized in biomedical education [36] [28]. However, modern educational reforms are increasingly shifting toward active learning strategies. Case-Based Learning (CBL), a problem-oriented teaching model centered on clinical cases, requires students to apply relevant professional knowledge and clinical thinking to solve problems [36]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of CBL and traditional learning methods across three critical biomedical education contexts: pharmacology, clinical research, and laboratory training, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of challenge-based versus traditional instructional research.

Quantitative Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Comparison

A systematic review and meta-analysis of CBL in pharmacy education offers high-level evidence of its effectiveness. The analysis, which included 11 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1,339 pharmacy students, provides standardized quantitative outcomes across several critical competencies [36] [28].

Table 1: Meta-Analysis Results of CBL vs. LBL in Pharmacy Education

| Outcome Measure | Statistical Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Exam Scores | SMD = 0.58, 95% CI [0.39, 0.77] | P < 0.05 |

| Communication/Collaboration Skills | RR = 2.49, 95% CI [1.17, 5.27] | P < 0.05 |

| Problem-Solving Abilities | RR = 2.19, 95% CI [1.26, 3.80] | P < 0.05 |

| Clinical Practice Skills | RR = 2.39, 95% CI [1.46, 3.92] | P < 0.05 |

| Student Satisfaction | RR = 1.63, 95% CI [1.22, 2.18] | P < 0.05 |

SMD: Standardized Mean Difference; RR: Risk Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval

The data demonstrates that CBL consistently leads to better outcomes than LBL, with significantly higher exam scores and a greater than two-fold likelihood of students developing enhanced communication, problem-solving, and clinical skills [36].

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Case Study: Pharmacology Education

A comparative study in pharmacology for second-year MBBS students employed a crossover design to evaluate CBL against traditional teaching methods (TTM) [37] [38].

- Objective: To compare the effectiveness of CBL and TTM in teaching topics like myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, and anti-ulcer drugs in terms of knowledge gained [37] [38].

- Participants: 90 second-year MBBS students [38].

- Methodology:

- Students were divided into two groups: Didactic Lecture (DDL) and CBL.

- The CBL group was further subdivided into smaller subgroups of 15 students.

- The study was conducted over 8 sessions for 4 separate topics.

- A crossover was performed after the first topic, meaning groups switched learning methods for subsequent topics to mitigate bias.

- Knowledge gain was assessed via pre-test and post-test questionnaires for both groups [38].

- Outcome Analysis: Paired t-tests were used to analyze pre- and post-test scores within groups, and an unpaired t-test was used to compare post-test scores between the DDL and CBL groups [38].

Case Study: Laboratory Training in Clinical Biochemistry

A study on laboratory training designed a student-centred program based on CBL to improve quality management awareness according to ISO 15189 requirements [39].

- Objective: To improve students' awareness and ability in total testing process (TTP) quality management, with a focus on error-prone preanalytical and postanalytical stages [39].

- Participants: 357 undergraduate medical laboratory science students randomly assigned to a test group (CBL, n=185) and a control group (traditional training, n=172) [39].

- CBL Intervention (4-Stage Protocol):

- Establish Testing Process: Students received a patient case 2-4 days before class. They individually answered questions about the diagnosis, detection indicators, and the pre-analysis, analysis, and post-analysis procedures. Answers were then shared and discussed in small groups with teacher facilitation (≈30 minutes).

- Clarify Principles: Instruction on current methods and principles for the tests (≈30 minutes).

- Improve Operational Skills: Hands-on laboratory work, including evaluation of lab and equipment conditions, use of internal controls, and sample processing per standard operating procedures (SOPs) (≈45 minutes).

- Review and Continuous Improvement: Analysis of results combined with ISO 15189 requirements. Students learned to identify abnormal results and decide if they could be reported, repeating the check if necessary (≈30 minutes) [39].

- Control Group: Received teacher-centred experimental teaching where the instructor explained principles, operations, and medical significance before students performed the experiment [39].

- Outcome Evaluation: Assessment included laboratory operational skills and total examination scores, alongside a questionnaire survey [39].

Case Study: Clinical Research and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

A study investigated the impact of converting a Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) course from a traditional format to a CBL one utilizing virtual patients [29].

- Objective: To compare student knowledge and knowledge retention of antibiotic dosing and monitoring between a traditional 4-credit TDM course and a redesigned 2-credit CBL course [29].

- Participants: Third-year pharmacy (P3) students from the traditional course (Spring 2019) and the redesigned CBL course (Spring 2020) [29].

- CBL Intervention:

- The course was reduced from 4 to 2 credit hours but redesigned to be case-based.

- Classes involved conceptual lectures with practice cases, followed by a "case-day."

- Students completed virtual patient cases within a simulated Electronic Health Record (EHR) to mimic an inpatient Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experience (APPE).

- Students completed 3 practice and 3 graded cases on antimicrobial dosing and monitoring.

- The grade distribution shifted to emphasize application: graded cases (40%), exams (50%), and pre-class assignments/quizzes (10%) [29].

- Traditional Comparison: The traditional course spent over 85% of class time on concepts and practice problems, with grades based solely on exams (80%) and quizzes (20%) [29].

- Data Collection: Students completed a knowledge assessment immediately after the course and a knowledge retention assessment before their Internal Medicine APPE in their fourth year (P4) [29].

Visualizing the CBL Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the structured, iterative process common to CBL implementations in biomedical education, particularly evident in the laboratory training case study [39].

Figure 1: The CBL Cycle in Biomedicine. This workflow maps the student journey from initial case exposure to competency achievement, highlighting the integration of self-directed learning, collaboration, and practical application [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for CBL Experiments

Successful implementation of CBL in biomedical education relies on specific "research reagents" or essential components.

Table 2: Essential Components for Implementing CBL

| Component | Function in the CBL Experiment |

|---|---|

| Clinical Cases | Adapted from real clinical scenarios, these form the core problem statement that drives learning and application of knowledge [36] [38]. |

| Simulated Electronic Health Record (EHR) | Provides an authentic, risk-free environment for students to practice therapeutic drug monitoring, data analysis, and clinical decision-making [29]. |

| Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) | Guide students in practical laboratory work, ensuring adherence to quality standards like ISO 15189 and fostering professional habits [39]. |

| Structured Assessment Rubrics | Tools for objectively evaluating competencies beyond factual recall, including laboratory skills, problem-solving, and clinical reasoning [39] [29]. |

| Facilitator Guidelines | A guide for instructors to ensure consistency in facilitating group discussions, providing feedback, and guiding—rather than directing—student learning [29]. |

| PCTA | PCTA |

| Dexamethasone 17-acetate | Dexamethasone 17-acetate, CAS:25122-35-4, MF:C24H31FO6, MW:434.5 g/mol |

The evidence from pharmacology, clinical research, and laboratory training consistently demonstrates the efficacy of CBL over traditional methods. The quantitative meta-analysis shows clear, significant benefits across multiple learning domains [36] [28]. The individual case studies reveal that these benefits persist even when contact hours are substantially reduced, as seen in the TDM course, and that CBL effectively fosters crucial practical skills and knowledge retention [39] [29].

A key strength of CBL is its engagement of students through interaction with content, peers, and self, moving them from passive recipients to active participants in their education [40]. Furthermore, online CBL has shown promise in fostering clinical reasoning, though challenges like decreased engagement and unrealistic case presentations must be managed, often through blended learning approaches [41].

In conclusion, for educating the next generation of biomedical researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, CBL provides a superior pedagogical framework. It effectively bridges the gap between theoretical knowledge and the complex, practical competencies required in real-world clinical and laboratory settings.

Integrating Digital Tools and Simulations for Enhanced Learning Experiences

Higher education institutions are actively reviewing teaching methodologies to align graduate competencies with evolving socioeconomic and professional demands [21]. In biomedical science and drug development education, this has catalyzed a transition from traditional, content-delivery models towards innovative, experiential approaches [5] [42]. Among these, Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) has emerged as a prominent pedagogical strategy, emphasizing real-world problem-solving and competency development [21]. Concurrently, digital tools like clinical simulations and virtual laboratories are gaining traction for their ability to provide immersive, low-risk training environments [42] [43]. This guide objectively compares the performance of Challenge-Based Learning against traditional instructional models within biomedical education, presenting supporting experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Defining the Educational Frameworks

Challenge-Based Learning (CBL)

CBL is a student-centered approach that immerses learners in real-world, collaborative problems requiring the application of knowledge to develop actionable solutions [5] [21]. It shifts the educator's role from a knowledge transmitter to a facilitator who guides the learning process, provides resources, and offers timely feedback [21]. In CBL, the problems or "challenges" are often crafted in collaboration with industry partners, adding formality and rigor to the proposed solutions and enhancing professional relevance [5].

Traditional Learning Models

Traditional learning (TL) in this context refers to instructor-centered methodologies primarily based on lectures and structured course activities, where academic performance is often assessed through final exams [5]. While traditional methods may incorporate projects, they typically follow more predefined steps and are less open-ended than CBL challenges [5].

The Role of Digital Simulations

Although distinct from CBL, digital simulations often serve as powerful enabling tools within this framework. They create synthetic recreations of authentic processes or situations, allowing students to develop knowledge, competencies, and professional attitudes through direct engagement and hands-on practice without real-world risks [42] [43]. In biomedical sciences, simulations range from virtual laboratories for basic science principles to clinical scenarios for developing patient-facing skills [42] [43].

Comparative Experimental Data on Academic Outcomes

Robust, large-scale studies provide quantitative evidence comparing the efficacy of these educational approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Academic Performance in Engineering Education (Alvarez et al., 2025)

| Metric | Traditional Learning (PL) Model | Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) Model | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Student Performance (Average Final Course Grades) | Baseline | +9.4% Improvement [5] | |

| Project/Challenge Grades | Project Average Grades | Challenge Average Grades | Comparable [5] |

| Student Perception (Favorable View on Competency Development & Problem-Solving) | Not Reported | 71% of Students | Not Applicable [5] |

Table 2: Comparative Outcomes in Statistics Education for Health Disciplines (PMC, 2025)

| Metric | Traditional Learning (Online) | Competency-Based Learning (Online) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Score Improvement (Hypothesis Testing) | Improved | Improved | p = 0.02 [44] |

| Knowledge Score Improvement (Measures of Central Tendency) | Improved | Improved | p = 0.001 [44] |

| Knowledge Score Improvement (Research Design) | Improved | Improved | p = 0.001 [44] |

| Overall Knowledge Mean Scores | Improved | Improved | No significant difference (p = 0.10) [44] |

| Current Statistics Self-Efficacy (CSSE) | Improved (p < 0.001) | Improved (p < 0.001) | Significant in both groups [44] |

| Self-Efficacy to Learn Statistics (SELS) | Improved (p = 0.02) | Improved (p < 0.001) | Significant in both groups [44] |

Table 3: Student Perception of Clinical Simulations in Biomedical Science (Sciencedirect, 2025)

| Perception Metric | Percentage of Students in Agreement |

|---|---|

| Positive Learning Experience | 97% [43] |

| Enjoyed Taking Part | 100% [43] |

| Supported Development of Communication & Teamwork | 90% [43] |

| Improved Perceived Employability | 84% [43] |

| Desire for Simulations Embedded in Core Curriculum | 90% [43] |

| Belief Simulations are Better than Traditional Dyadic Styles | 91% [43] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols in Educational Research

Protocol 1: Quasi-Experimental Comparison of CBL vs. Traditional Models

A large-scale quasi-experimental study compared the CBL and traditional (PL) models over seven semesters [5].

- Population and Scope: The study involved 1705 freshman engineering students (43% in PL, 57% in CBL) in physics courses, spanning from Spring 2018 to Spring 2021 [5].

- Intervention (CBL Model): The CBL model presented students with crafted, ad-hoc challenges tailored to their semester and major. These challenges were designed to explicitly integrate concepts from physics, math, and computing, often with input from industrial training partners to ensure real-world relevance [5].

- Comparison (PL Model): The traditional model was based on the institution's previous educational framework, which emphasized lectures and final exams [5].