Cross-Linking in Polylactic Acid: Strategic Modulation of Crystallization Behavior and Degradation Kinetics for Advanced Applications

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of how cross-linking strategies fundamentally alter the crystallization dynamics and degradation profiles of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and its copolymers.

Cross-Linking in Polylactic Acid: Strategic Modulation of Crystallization Behavior and Degradation Kinetics for Advanced Applications

Abstract

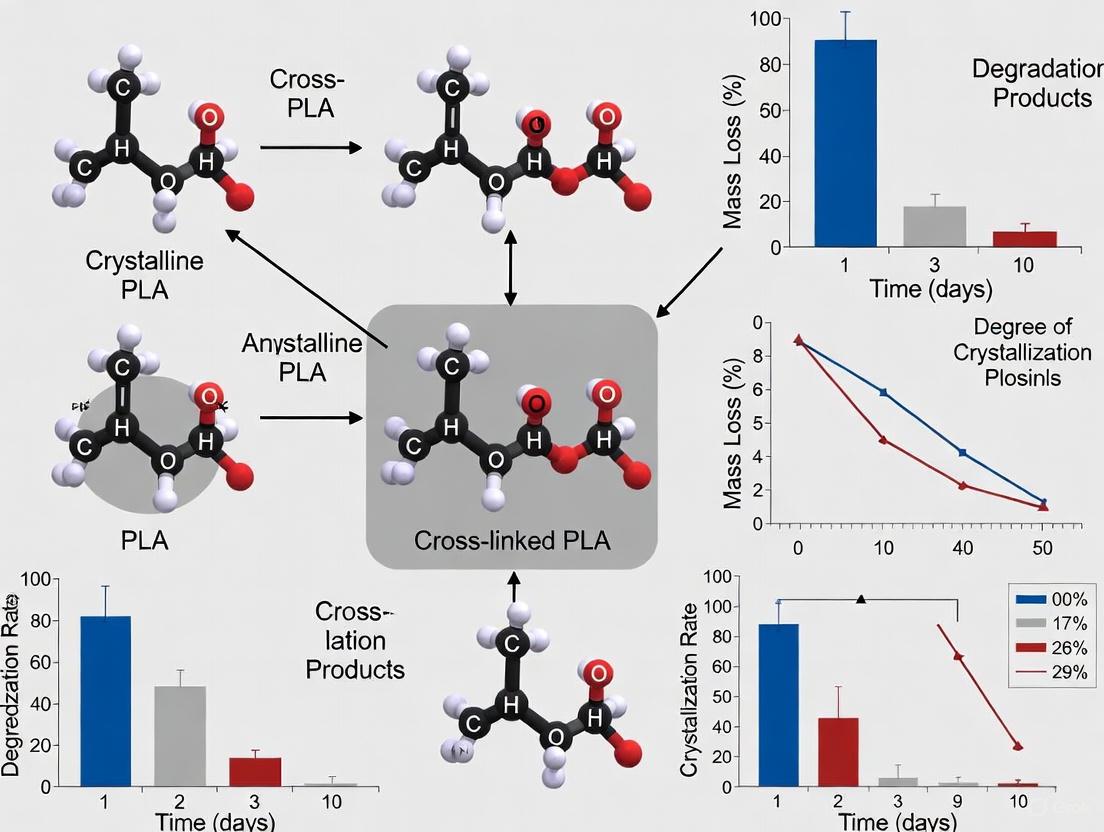

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of how cross-linking strategies fundamentally alter the crystallization dynamics and degradation profiles of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) and its copolymers. We systematically examine the foundational principles governing cross-link formation in PLA systems, explore advanced methodological approaches for their implementation, address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present rigorous validation through comparative performance analysis. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, this article establishes clear structure-property relationships crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to engineer PLA-based materials with precisely tailored degradation rates and crystalline morphologies for biomedical devices, controlled drug delivery systems, and sustainable packaging applications.

Fundamental Mechanisms: How Cross-Linking Chemically Alters PLA Crystallization and Degradation Pathways

Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is a leading biodegradable and bio-based aliphatic polyester, derived from renewable resources like corn and sugarcane, positioning it as a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics [1]. Its excellent biocompatibility and comparable mechanical properties to many engineering plastics have fueled its adoption in fields ranging from biomedical implants to food packaging [2] [1]. However, the widespread application of PLA is often constrained by inherent limitations, such as insufficient melt strength for foaming, slow crystallization rate, and relatively low heat resistance [3] [4] [5].

To overcome these challenges, strategic modifications of PLA’s polymer architecture are essential. Among these, the formation of cross-linked networks has emerged as a powerful technique. Cross-linking can significantly enhance PLA's thermal stability, mechanical properties, and melt strength, which is particularly crucial for producing high-performance foams and durable goods [3] [1]. This review provides a comparative analysis of two primary strategies for forming cross-links in PLA systems: in-situ cross-linking during processing and reactive compatibilization in polymer blends. The discussion is framed within the context of a broader thesis, investigating how these cross-link formation methods distinctly influence two critical aspects of PLA performance: its crystallization behavior and its hydrolytic degradation profile. Understanding these structure-property relationships is vital for researchers and scientists to tailor PLA materials for specific applications, whether the goal is to delay degradation for long-term implants or accelerate it for disposable packaging.

In-situ Cross-Linking Strategies

In-situ cross-linking refers to the process of forming covalent bonds between polymer chains during the material's processing, such as extrusion or hot-pressing. This method is highly valued for its ability to enhance the melt strength and thermo-mechanical properties of PLA without requiring pre-modification of the base resin.

Chemical Cross-Linking via Peroxide Initiators

A prominent in-situ approach involves the use of peroxide initiators and co-agents. In one study, a cross-linked network was successfully created in a PLA/poly(4-hydroxybutyrate) (P4HB) blend using bis(tert-butylperoxy isopropyl) benzene (BIBP) as the peroxide initiator and triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) as the co-agent [3]. The mechanism involves BIBP decomposing under heat to generate free radicals, which then abstract hydrogen from the polymer backbone. The TAIC, with its multiple allyl groups, readily reacts with these polymer radicals, forming a cross-linked network that bridges PLA and P4HB chains. This process not only increases the melt strength of the blend but also compatibilizes the phases, reducing interfacial stress concentrations [3]. The resulting cross-linked foams exhibited a closed-cell structure with a high volume expansion ratio (VER), contributing to excellent impact resistance and thermal insulation properties [3].

Table 1: Key Reagents for Chemical Cross-Linking of PLA

| Reagent Name | Function | Mechanism & Role |

|---|---|---|

| Bis(tert-butylperoxy isopropyl) benzene (BIBP) | Peroxide Initiator | Decomposes thermally to generate free radicals that initiate cross-linking by abstracting hydrogen from polymer chains. |

| Triallyl Isocyanurate (TAIC) | Cross-linking Co-agent | Multi-functional monomer whose allyl groups form bridges between polymer radicals, creating a 3D network. |

| Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) | Cross-linking Co-agent | Acrylate-functionalized molecule that reacts with radicals to link multiple polymer chains. |

Cross-Linking via High-Energy Irradiation

An alternative physical method for in-situ cross-linking employs high-energy irradiation, such as electron beam (E-beam) or gamma rays. When PLA is exposed to ionizing radiation, radicals are generated directly on its polymer chains, which can subsequently recombine to form cross-links [1]. However, PLA has a tendency to undergo chain scission under irradiation. To promote cross-linking over degradation, polyfunctional monomers like TAIC, trimethallyl isocyanurate (TMAIC), or trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) are often added [1]. These monomers possess multiple reactive sites that enhance the efficiency of network formation. The cross-linked PLA materials produced via irradiation display improved heat stability and can become rubbery and stable at temperatures even above their melting point (( T_m )) [1].

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting and implementing an in-situ cross-linking strategy for PLA, incorporating both chemical and irradiation methods.

Reactive Compatibilization in Blends

Reactive compatibilization is a powerful strategy for creating cross-like structures at the interface of polymer blends, particularly for immiscible pairs like PLA and polyolefins. This method improves adhesion between phases and stabilizes the blend morphology, leading to enhanced mechanical properties.

Mechanism and Reagents

The core principle involves introducing a reactive component that can chemically interact with both phases of the blend during melt processing. For instance, in PLA/PE blends, telechelic hydroxyl-functional PE can be synthesized to react with the end groups of PLA chains [6]. The efficiency of this reaction can be dramatically accelerated by employing catalysts that localize at the interface, such as stannous octoate, leading to a finer dispersion of the dispersed phase and improved interfacial adhesion [6]. Similarly, in PLA/PP blends, a multifunctional agent like trimethylolpropane tri-acrylate (TMPTA) under in-situ UV irradiation can form PLA-TMPTA-PP copolymers, which act as compatibilizers, reducing the size of the dispersed PP domains and improving the overall blend compatibility [4].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Reactive Compatibilization of PLA Blends

| Reagent Name | Function | Application & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Telechelic hydroxyl-functional PE | Reactive Polymer | End-functionalized polymer that reacts with PLA chain ends, forming a block copolymer at the interface of PLA/PE blends. |

| Trimethylolpropane tri-acrylate (TMPTA) | Multifunctional Agent | Forms copolymers with PLA and PP under UV irradiation, compatibilizing the blend interface. |

| Stannous Octoate | Catalyst | Localizes at the polymer-polymer interface and accelerates transesterification or coupling reactions. |

Comparative Effects on Crystallization

The introduction of cross-links and compatibilized structures has a profound and complex impact on the crystallization behavior of PLA, which is a critical factor determining its final mechanical and thermal properties.

Nucleation and Crystal Growth

Cross-linked networks can influence crystallization in two opposing ways. On one hand, they can restrict the mobility of polymer chains, thereby impeding the growth of large crystals and potentially reducing the overall degree of crystallinity [7]. On the other hand, the interfaces in compatibilized blends or the cross-linked network itself can act as nucleation sites. Research on reactively compatibilized PLA/PP blends showed that the compatibilized interface assisted in the nucleation of PLA, leading to an increased spherulite density compared to neat PLA [4]. The cross-linking strategy in PLA/P4HB blends was also designed to increase the number of cell nucleation sites during foaming, which is indirectly linked to the crystallization behavior of the polymer matrix [3].

Crystal Form and Stability

PLA can crystallize in different forms, with the α-form being the most thermodynamically stable and the α′-form being a metastable disordered form that develops at lower crystallization temperatures [2]. The crystal form has a significant effect on material properties; α-form crystals generally provide a higher modulus and better barrier properties but can lead to brittleness, whereas α′-form structures are associated with higher tensile ductility [2]. The presence of a cross-linked network can alter the crystallization kinetics and the conditions under which these different forms develop, thereby providing a means to control the final material properties. For example, a higher cross-link density would be expected to favor the formation of the less ordered α′-form due to restricted chain mobility.

Table 3: Comparative Data: Cross-Link Effects on Crystallization and Properties

| System & Strategy | Effect on Crystallization | Resultant Key Property Changes |

|---|---|---|

| PLA/P4HB + In-situ Cross-link [3] | Increased melt strength; increased number of nucleation sites. | Formation of closed-cell foams with high volume expansion ratio (VER); excellent impact resistance and thermal insulation. |

| PLA/PP + Reactive Compatibilization [4] | Interface-assisted nucleation; increased PLA spherulite density. | Improved dispersion (smaller PP domains); enhanced compatibility and mechanical properties of the blend. |

| Cross-linked PLLA Networks [7] | Restricted chain mobility; reduced crystallinity (can be made amorphous with low ( M_c )). | Enhanced tensile strength; retained form stability during degradation. |

| General α-form vs. α′-form PLA [5] [2] | α-form: higher crystallinity, more ordered. α′-form: lower crystallinity, disordered. | α-form: Higher modulus, better heat resistance, better barrier properties. α′-form: Higher ductility. |

Comparative Effects on Hydrolytic Degradation

The degradation profile of PLA is a paramount consideration, especially for biomedical and environmental applications. Cross-linking fundamentally alters the hydrolysis mechanism and kinetics.

Mechanism: Surface Erosion vs. Bulk Erosion

Linear, semi-crystalline PLA typically degrades via bulk erosion, where water penetrates the entire specimen, causing random chain scission throughout the material. This leads to a gradual loss of mechanical properties while the mass remains largely unchanged until the material finally fragments [7]. In contrast, cross-linked PLA networks tend to degrade via surface erosion. In this mechanism, hydrolysis occurs primarily at the surface of the material, leading to a linear mass loss over time while the bulk of the material maintains its mechanical integrity and form stability for a longer period [7]. This phenomenon is because the dense network structure hinders the penetration of water into the bulk.

The Role of Cross-link Density

The density of the cross-linked network, often characterized by the average molecular weight between cross-links (( Mc )), is a critical factor controlling the degradation rate. Studies on PLLA-based networks have shown that a lower ( Mc ) (higher cross-link density) results in a slower degradation rate and confines the degradation to a thinner layer at the surface [7]. For example, a network with an ( Mc ) of 1400 g/mol showed degradation confined to the outer surface, whereas a network with an ( Mc ) of 3500 g/mol exhibited degradation up to a 400 μm layer from the surface [7]. Furthermore, the crystalline regions that form during the degradation process, as the chains become more mobile, can further slow down the degradation, as they are more resistant to hydrolysis than amorphous regions [2] [8].

The diagram below summarizes the divergent degradation pathways for linear versus cross-linked PLA and the key factors influencing the process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Methodologies

This section provides a consolidated reference for the key reagents and experimental protocols central to researching cross-link formation in PLA.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for PLA Cross-Linking Research

| Category | Reagent | Primary Function in PLA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Peroxide Initiators | Bis(tert-butylperoxy isopropyl) benzene (BIBP) | Generates free radicals to initiate cross-linking reactions during thermal processing. |

| Cross-linking Co-agents | Triallyl Isocyanurate (TAIC), Trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA) | Multi-functional monomers that bridge polymer radicals to form a three-dimensional network. |

| Catalysts | Stannous Octoate (Sn(Oct)â‚‚) | Catalyzes transesterification and coupling reactions, especially effective at polymer interfaces. |

| Reactive Polymers | Telechelic hydroxyl-functional PE | Acts as a macromolecular compatibilizer by reacting with PLA end-groups in blends. |

| TK216 | TK216 is a small molecule inhibitor for research, targeting ETS transcription factors and microtubules. It is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | |

| INDY | INDY, MF:C12H13NO2S, MW:235.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: In-situ Cross-Linking and Foaming

The following methodology, adapted from a cited study, outlines a standard procedure for creating and evaluating in-situ cross-linked PLA foams [3].

1. Materials Preparation:

- Polymer Resins: Dry PLA (e.g., LX175) and P4HB pellets in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 24 hours to prevent hydrolysis during processing.

- Cross-linking Additives: Weigh bis(tert-butylperoxy isopropyl) benzene (BIBP) and triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) accurately. Typical concentrations are in the range of 0.5-1.5 parts per hundred resin (phr) for BIBP and 1-3 phr for TAIC.

2. Melt Blending and Cross-Linking:

- Utilize an internal mixer (e.g., Haake Rheomix) or a twin-screw extruder.

- Set the processing temperature to a range that melts the polymers but is below the rapid decomposition temperature of the peroxide (e.g., 170-190°C).

- Introduce the dried PLA and P4HB pellets and allow them to melt and mix.

- Add the TAIC co-agent and BIBP peroxide initiator to the melt.

- Mix for a specific time (e.g., 5-10 minutes) to ensure homogeneous dispersion and allow the cross-linking reaction to proceed.

3. Foaming Process with Supercritical COâ‚‚:

- The blended and cross-linked material is compression-molded into sheets.

- The sheets are placed in a high-pressure vessel, which is then heated to the foaming temperature (e.g., 120-160°C).

- Introduce supercritical COâ‚‚ (sc-COâ‚‚) as the physical blowing agent at a specified pressure (e.g., 10-20 MPa) and allow sufficient time for saturation.

- Release the pressure rapidly to induce thermodynamic instability and cell nucleation, resulting in a foam structure.

4. Characterization and Analysis:

- Cell Structure: Analyze the foam morphology (cell size, density, open/closed cell content) using scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

- Gel Content: Determine the extent of cross-linking by Soxhlet extraction with an appropriate solvent (e.g., CHCl₃) to measure the insoluble gel fraction.

- Thermal Properties: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to analyze thermal transitions (Tg, Tc, Tm) and degree of crystallinity.

- Mechanical Performance: Perform impact resistance tests (e.g., Izod or Charpy) and compression tests to evaluate mechanical improvements.

- Melt Strength: Use a rheometer to measure the melt strength and viscoelastic properties of the cross-linked blend.

The strategic formation of cross-links in PLA, whether through in-situ techniques or reactive compatibilization, offers a powerful toolbox for enhancing its material properties. In-situ cross-linking with peroxides and co-agents is highly effective for improving melt strength and creating high-performance, closed-cell foams with excellent thermal insulation and impact resistance. Reactive compatibilization, on the other hand, is indispensable for creating high-performance PLA blends with otherwise immiscible polymers, leading to stabilized morphologies and enhanced mechanical properties.

The choice of strategy has profound and predictable consequences for both the crystallization behavior and the hydrolytic degradation of PLA. Cross-linking can tailor crystallization by providing nucleation sites while potentially limiting crystal growth, influencing toughness and heat resistance. More distinctly, it shifts the degradation mechanism from bulk to surface erosion, providing a means to control the lifetime and maintain the structural integrity of PLA products in use. For researchers and product developers, the decision between these strategies must be guided by the application's specific requirements: seeking enhanced thermo-mechanical performance and processability, or precisely managing the degradation profile for biomedical or specific environmental end-of-life scenarios.

Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) is a leading biobased and biodegradable polymer with significant potential to replace petroleum-based plastics in applications ranging from medical devices to packaging [9]. However, its widespread adoption is limited by inherent shortcomings, including slow crystallization kinetics, brittleness, and low heat deflection temperature [9] [10]. Crosslinking has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance PLA's mechanical and thermal properties, creating a network structure that significantly influences crystallization behavior [1]. Understanding how crosslinking affects nucleation, crystal growth rates, and ultimate crystallinity is essential for tailoring material properties to specific applications.

The crystallization behavior of semi-crystalline polymers like PLA directly governs critical performance characteristics, including tensile strength, modulus, impact resistance, and thermal stability [5] [9]. For cross-linked PLA, the network structure imposes topological constraints on polymer chains, fundamentally altering their ability to rearrange into ordered crystalline structures. This creates a complex interplay between crosslink density, crystallization kinetics, and final material properties that researchers must navigate to optimize PLA for demanding applications where current performance is insufficient.

Crosslinking Methodologies for PLA

High-Energy Radiation Crosslinking

Crosslinking of PLA using high-energy radiation, particularly electron beam and gamma irradiation, represents a prominent physical modification method [1]. Unlike chemical crosslinking, this approach can be performed on pristine PLA without prerequisite functionalization, as radicals are generated directly on polymer chains upon irradiation. However, PLA predominantly undergoes chain scission rather than crosslinking when irradiated alone, leading to molecular weight reduction and property deterioration [1]. To overcome this limitation, polyfunctional monomers are incorporated as crosslinking co-agents.

Table 1: Crosslinking Co-Agents for Radiation-Induced PLA Crosslinking

| Co-Agent | Chemical Type | Optimal Concentration | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) | Cyanurate derivative | ~3% | Most optimal conditions at 30-50 kGy dose; improved heat stability and mechanical properties | [1] |

| Trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TMPTMA) | Acrylate ester | 1-3% | Enhanced crosslinking density; increased gel content | [1] |

| 1,6-Hexanediol diacrylate (HDDA) | Di-functional acrylate | 1-3% | Improved network formation; retarded degradation | [1] |

The crosslinking process with these co-agents typically employs radiation doses between 30-50 kGy, with higher doses promoting increased crosslink density but risking predominant chain scission [1]. The resulting crosslinked PLA exhibits substantially improved heat stability and mechanical properties, particularly at elevated temperatures, where the material transitions to a rubbery state rather than melting [1].

Stereocomplex Crosslinking

An alternative physical crosslinking approach utilizes PLA stereocomplexation between poly(L-lactide) (PLLA) and poly(D-lactide) (PDLA) enantiomers [11]. This method creates a physical network through stereocomplex crystallites that act as crosslinking points, offering superior thermal stability compared to homocrystallized PLA. The stereocomplex formation requires remarkably short sequence lengths of only approximately 7 repeating units, making it particularly suitable for multiblock copolymers where longer sequences for homocrystallization may be sterically hindered [11].

In sophisticated material designs, researchers have developed multiblock copolymers such as PCL-PLLA and PGACL-PDLA, where one segment provides structural support while the other enables stereocomplex crosslinking [11]. This approach allows precise control over degradation profiles and mechanical property evolution during use, making it particularly valuable for biomedical applications like tissue fixation devices that require increased flexibility during the healing process [11].

Comparative Crystallization Kinetics: Cross-Linked vs. Modified PLA

Experimental Methodology for Crystallization Analysis

The investigation of crystallization kinetics in PLA systems relies on standardized experimental protocols that enable direct comparison between different modifications. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) serves as the primary analytical technique, with both isothermal and non-isothermal methods providing critical kinetic parameters [12] [13] [14].

Isothermal Crystallization Protocol: Samples are first heated from room temperature to 195°C at 30°C/min and held for 1 minute to erase thermal history [14] [15]. They are then rapidly cooled (80°C/min) to predetermined isothermal crystallization temperatures (typically between 80-140°C) and held until crystallization is complete, as indicated by the return of the exotherm to baseline [13] [14]. This protocol enables determination of crystallization half-time (tâ‚/â‚‚) and Avrami kinetic parameters.

Non-Isothermal Crystallization Protocol: Samples undergo heating from room temperature to 200°C at 10°C/min to determine glass transition temperature (Tg), cold crystallization temperature (Tcc), and melting temperature (Tm) [14]. Cooling rate variations provide insights into crystallization rate dependence on thermal history, particularly relevant for processing techniques like injection molding.

Complementary techniques include polarized optical microscopy (POM) for spherulitic morphology observation [5] [14], X-ray diffraction (XRD) for crystalline structure identification [12] [13], and wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) for crystal form determination [5] [11].

Quantitative Crystallization Kinetics Data

Table 2: Comparative Crystallization Kinetics of PLA Systems

| PLA System | Modification Type | Half-Crystallization Time (tâ‚/â‚‚) | Crystallization Temperature (Tᶜ) | Maximum Crystallinity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLA (3100HP) | Unmodified | >5 min (non-isothermal) | ~100°C (cooling) | 25-30% | [10] |

| PLA + 1% EBS | Nucleating Agent | Lowest at 110°C (isothermal) | Increased | ~40% | [13] |

| PLA + 1% Orotic Acid | Nucleating Agent | <5 min (from 80 min for neat PLA) | Reduced from 90°C to 70°C | Significantly increased | [13] |

| PLA + 15% Tributyrin | Plasticized | Decreased | Reduced | Enhanced | [12] [14] |

| PLA + 15% USOP | Bio-based Plasticizer | Decreased | Reduced | Enhanced | [12] [14] |

| Cross-linked PLA (with TAIC) | Cross-linked | Increased (constrained chains) | Unreported | Limited (~20% gel content) | [1] |

The data reveal that cross-linked PLA systems typically exhibit constrained crystallization kinetics due to restricted chain mobility, resulting in longer half-times and potentially lower ultimate crystallinity compared to nucleated or plasticized systems [1]. In contrast, nucleating agents like EBS and orotic acid dramatically accelerate crystallization, reducing half-times from minutes to seconds under optimal conditions [13]. Bio-based plasticizers such as used sunflower oil (USOP) also enhance crystallization rates by improving chain mobility, though less profoundly than specialized nucleating agents [12] [14].

Research Reagents and Materials Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PLA Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) | Crosslinking co-agent | Radiation crosslinking | Polyfunctional; enhances crosslinking efficiency under e-beam/Gamma |

| PLLA/PDLA enantiomers | Stereocomplex formation | Physical crosslinking | Forms stereocomplex crystallites with higher Tm (~230°C) |

| Zinc PhenylPhosphonate | Nucleating agent | Crystallization enhancement | Most effective nucleating agent; significantly reduces tâ‚/â‚‚ |

| Orotic Acid (OA) | Organic nucleator | Crystallization acceleration | Reduces crystallization time from 80 min to <5 min at 1% loading |

| Ethylene Bis-Stearamide (EBS) | Nucleating agent | Crystallization promotion | At 1%, produces fastest crystallization at 110°C |

| Used Sunflower Oil (USOP) | Bio-based plasticizer | Flexibility & crystallization modifier | Increases spherulite size; reduces crystallization activation energy |

| Tributyrin (TB) | Conventional plasticizer | Flexibility & crystallization modifier | Reduces Tg; enhances crystallization rate more than USOP |

| AP521 | AP521, CAS:151227-08-6, MF:C20H19ClN2O3S, MW:402.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Xl-999 | XL999 | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit provides researchers with essential materials for designing experiments to investigate and manipulate crystallization behavior in PLA systems. The selection of specific reagents depends on the target properties and modification strategy, whether aiming for enhanced crystallization rates (nucleating agents), improved flexibility (plasticizers), or network formation (crosslinking agents).

Interrelationship Between Modification Approaches

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between different PLA modification strategies and their subsequent effects on crystallization behavior and final material properties:

This conceptual framework reveals that crosslinking, nucleation, and plasticization exert distinct influences on the crystallization process. While nucleating agents and plasticizers generally promote crystallization kinetics through increased nucleation sites and enhanced chain mobility respectively, crosslinking typically restricts chain mobility and thus slows crystallization [13] [1] [14]. The optimal modification strategy depends critically on the target application and required balance between properties such as heat resistance, mechanical strength, and degradation behavior.

Implications for Material Performance and Applications

The crystallization behavior of cross-linked PLA directly governs its thermomechanical properties and practical applicability. For medical devices such as tissue fixation systems, the evolution of mechanical properties during degradation is particularly critical. Research demonstrates that properly designed cross-linked PLA systems can exhibit increasing flexibility during degradation—a desirable trait for supporting healing tissues [11]. This behavior contrasts with conventional PLA, which typically becomes more brittle as degradation proceeds.

In applications requiring enhanced heat resistance, such as food containers or electronic housings, achieving high crystallinity is essential for raising the heat deflection temperature (HDT). Studies show that highly crystallized PLA components can achieve HDT values approaching 90°C, making them suitable for higher-temperature applications [10]. However, crosslinked systems face inherent challenges in achieving high crystallinity degrees due to restricted chain mobility, potentially limiting their HDT enhancement compared to optimally nucleated systems.

The selection of modification approach ultimately depends on application requirements. Crosslinking excels where dimensional stability at elevated temperatures, controlled degradation profiles, or shape memory properties are prioritized. Nucleation strategies prove superior when maximum crystallinity and crystallization rate are essential for manufacturing efficiency and ultimate properties. Emerging hybrid approaches that combine multiple modification strategies offer promising avenues for overcoming individual limitations and achieving optimized property profiles for demanding applications.

Hydrolytic degradation is a fundamental process that governs the lifetime and performance of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) in applications ranging from packaging to biomedicine. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the precise mechanisms of ester bond hydrolysis and the autocatalytic effects that accelerate degradation is crucial for designing materials with tailored service lives. This review provides a comparative analysis of how different chemical modifications, particularly cross-linking and chain extension, influence the hydrolysis kinetics and degradation pathways of PLA-based materials. The investigation of these mechanisms is set within the broader context of a thesis examining cross-link effects on crystallization and degradation in PLA research, addressing the critical need for predictive models that can guide material selection and development. By synthesizing experimental data from recent studies and presenting clear methodologies, this work serves as a practical resource for scientists seeking to control PLA degradation through strategic molecular design.

Fundamental Mechanisms of PLA Hydrolysis

Ester Bond Cleavage and Polymer Chain Scission

The hydrolytic degradation of PLA initiates with the penetration of water molecules into the polymer matrix, predominantly attacking the amorphous regions due to their lower packing density compared to crystalline domains [16] [17]. This intrusion leads to the cleavage of ester bonds (-CO-O-) along the polymer backbone through a nucleophilic substitution reaction. Water molecules target the carbonyl carbon of the ester group, resulting in chain scission and the generation of shorter polymer fragments with terminal carboxyl (-COOH) and hydroxyl (-OH) end groups [16]. Research indicates this cleavage occurs through two primary mechanisms: random chain scission, where ester bonds are cleaved at any point along the polymer chain, and end-chain scission, where hydrolysis occurs preferentially at terminal ester bonds [16]. The dominance of each mechanism depends on environmental conditions, with end-chain scission reported to be approximately ten times more frequent than random scission in acidic media [16].

The Autocatalytic Effect

A defining characteristic of PLA hydrolysis is its autocatalytic nature. As ester bonds cleave, they generate new carboxyl end groups that increase the local acidity within the polymer matrix [18] [19] [16]. These acidic groups catalyze further ester bond hydrolysis, creating a self-accelerating degradation cycle. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in larger, bulkier specimens where the acidic oligomers and monomers produced during degradation cannot readily diffuse out of the polymer matrix, leading to accelerated internal degradation known as "bulk erosion" [19]. In contrast, "surface erosion" occurs when the rate of degradation at the surface exceeds the rate of water diffusion into the bulk, which is more common in thinner specimens or under strongly alkaline conditions [19]. The autocatalytic effect creates a heterogeneous degradation profile, with the interior of a specimen often degrading faster than the surface, potentially leading to sudden mechanical failure as the internal structure compromises while the surface remains apparently intact [19].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PLA Hydrolytic Degradation Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Random Chain Scission | End-Chain Scission | Autocatalytic Bulk Erosion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of Attack | Ester bonds at any position along polymer chain | Ester bonds adjacent to chain ends | All accessible ester bonds, preferentially in polymer interior |

| Primary Products | Shorter polymer chains of variable length | Lactic acid monomers | Oligomers, lactic acid, and carboxyl-ended chains |

| Rate Influence | Determines rapid molecular weight decrease | Dominates in acidic environments | Accelerated by accumulation of acidic degradation products |

| Spatial Pattern | Homogeneous throughout water-accessible regions | Concentrated at chain termini | Heterogeneous - faster in specimen interior |

| Molecular Weight Change | Rapid decrease in average molecular weight | Slow decrease in molecular weight with monomer production | Bimodal molecular weight distribution during intermediate stages |

Figure 1: Autocatalytic Hydrolysis Mechanism in PLA. Water penetration initiates ester bond cleavage, generating acidic carboxyl end groups that catalyze further hydrolysis in a self-accelerating cycle.

Experimental Approaches to Studying PLA Hydrolysis

Standard Hydrolysis Protocols and Methodologies

Researchers employ standardized hydrolysis experiments to quantify PLA degradation rates under controlled conditions. A typical protocol involves immersing PLA specimens (films, compressed sheets, or molded items) in aqueous media at precisely controlled temperatures, with periodic sampling to monitor changes in key properties [20] [18] [16]. The selection of hydrolysis medium depends on the intended application—deionized water for fundamental studies, buffer solutions (e.g., phosphate buffer saline, PBS) for biomedical applications, or water-ethanol solutions for food packaging research [20] [19]. Temperature control is critical, with studies often conducted at elevated temperatures (40-95°C) to accelerate degradation for lifetime prediction, while physiological temperature (37°C) is used for biomedical applications [16]. Specimens are typically removed at predetermined intervals, thoroughly dried, and analyzed for molecular weight changes, mass loss, thermal properties, and mechanical performance.

Analytical Techniques for Monitoring Degradation

The progression of hydrolysis is tracked using multiple analytical techniques that provide complementary information. Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), also known as Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC), is the primary method for monitoring changes in molecular weight and molecular weight distribution, offering sensitive detection of chain scission events [18] [19] [16]. Thermal Analysis via Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) tracks changes in glass transition temperature (Tg), melting temperature (Tm), and crystallinity (Xc), which increase during hydrolysis due to enhanced chain mobility and reorganization [16]. Mass Loss measurements quantify the dissolution and release of water-soluble degradation products (monomers and oligomers) from the polymer matrix [18]. Additionally, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly ³¹P-NMR, can elucidate specific degradation mechanisms when specialized additives are involved [19].

Table 2: Core Analytical Methods for Monitoring PLA Hydrolysis

| Analytical Method | Parameters Measured | Information Obtained | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Mn, Mw, MWD | Average molecular weights and distribution breadth | Requires appropriate standards; sensitive to sample preparation |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Tg, Tm, ΔHm, Xc | Thermal transitions and degree of crystallinity | Heating rate and thermal history significantly affect results |

| Mass Loss Analysis | Residual mass percentage | Release of soluble degradation products | Must carefully dry samples; may plateau before complete degradation |

| Rheological Analysis | Melt viscosity, complex modulus | Changes in processability and mechanical integrity | Measurements sensitive to molecular architecture (branching) |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Chemical structure, end groups | Molecular structure changes, additive degradation | ¹H-NMR for general structure; ³¹P-NMR for phosphite additives |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Studying PLA Hydrolysis. The comprehensive characterization involves multiple analytical techniques after controlled hydrolysis to elucidate degradation mechanisms and kinetics.

Comparative Analysis of Modified PLA Systems

Cross-Linked and Chain-Extended PLA Systems

The incorporation of cross-links or chain extenders significantly alters the hydrolysis behavior of PLA by modifying its molecular architecture. Multifunctional epoxy-based chain extenders, such as Joncryl ADR-4300F, react with carboxyl and hydroxyl end groups of PLA chains, creating branched structures and increasing molecular weight [16]. Studies demonstrate that chain-extended PLA films exhibit significantly slower degradation rates compared to neat PLA across temperatures ranging from 40-95°C [16]. For instance, at 70°C, the time to reach the critical molecular weight for chain entanglement (approximately 8-10 kDa) increased from 10 hours for neat PLA to 25 hours for chain-extended PLA—a 150% improvement in stability [16]. This enhanced resistance to hydrolysis stems from the reduced concentration of accessible carboxyl end groups (which drive autocatalysis) and the increased molecular weight between cross-links, which impedes water penetration and chain mobility.

Elastomer-Modified PLA Blends

Blending PLA with polyolefin elastomers (POEs) represents another modification strategy aimed primarily at improving mechanical properties, but which also influences degradation behavior. Research shows that incorporating POEs (e.g., ethylene-1-octene copolymer) at 15 wt% alongside compatibilizers like POE-g-MA creates a more homogeneous system with improved interfacial compatibility [20]. This morphology reduces the volume and surface area of PLA exposed to aqueous solutions, thereby slowing the hydrolytic degradation rate compared to unmodified PLA [20]. However, the non-biodegradable nature of POEs means that while initial degradation is slower, the resulting composite is no longer fully biodegradable, presenting a trade-off between performance enhancement and environmental impact [20].

Additives for Accelerated Hydrolysis

In contrast to stabilization approaches, some applications benefit from accelerated hydrolysis. Phosphite-based additives, particularly distearyl pentaerythritol diphosphite (Weston 618F), have been shown to significantly enhance hydrolysis rates [19]. Studies demonstrate that PLA compounded with 0.8% phosphite exhibited a 57.7% reduction in molecular weight after 4 days at 58°C, compared to a 31.3% reduction for unmodified PLA [19]. The acceleration mechanism involves the hydrolysis of phosphites to generate acidic compounds (phosphorous acid) that catalyze ester bond cleavage [19]. This approach offers potential for controlling degradation in composting scenarios or for reducing the environmental persistence of PLA litter.

Table 3: Comparative Hydrolysis Performance of Modified PLA Systems

| PLA System | Modification Agent | Key Hydrolysis Findings | Molecular Weight Changes | Activation Energy (Ea) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neat PLA | None | Reference material; rapid autocatalytic degradation | Mn reduced by 31.3% after 4 days at 58°C [19] | 82.7 kJ/mol (40-95°C range) [16] |

| Chain-Extended PLA | Joncryl ADR-4300F (0.5 wt%) | Slower degradation; reduced autocatalysis | Time to reach Mn=10kDa at 70°C: 25h (vs. 10h for neat PLA) [16] | 92.3 kJ/mol (16% increase vs. neat PLA) [16] |

| Elastomer-Modified PLA | POE (15 wt%) + POE-g-MA | Reduced degradation due to lower PLA surface area | Not quantified; degradation rate lower than neat PLA [20] | Not reported |

| Accelerated-Hydrolysis PLA | Distearyl pentaerythritol diphosphite (0.8 wt%) | Significantly accelerated hydrolysis | Mn reduced by 57.7% after 4 days at 58°C [19] | Not reported |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying PLA Hydrolysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Hydrolysis Research | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA Resins | Base material for hydrolysis studies | NatureWorks 2003D (4% D-isomer), 4032D, Luminy L175 (>99% L-isomer) | D-isomer content controls crystallinity; affects degradation rate |

| Chain Extenders | Modify molecular architecture to resist hydrolysis | Joncryl ADR-4300F (epoxy-functional) | Reacts with carboxyl end groups; reduces autocatalytic sites |

| Hydrolysis Accelerators | Enhance degradation rate for controlled lifetimes | Distearyl pentaerythritol diphosphite (Weston 618F) | Hydrolyzes to acidic products that catalyze ester cleavage |

| Compatibilizers | Improve interface in PLA blends | POE-g-MA (polyolefin elastomer grafted with maleic anhydride) | Enhances homogeneity; reduces PLA phase exposure to moisture |

| Hydrolysis Media | Environment for degradation studies | Deionized water, phosphate buffer (PBS), water-ethanol solutions | Choice depends on intended application (medical, packaging) |

| Analytical Standards | Calibration and quantification | Polystyrene standards (SEC), reference materials for DSC | Essential for accurate molecular weight and thermal measurements |

| MT-4 | MT-4, MF:C21H23N5O, MW:361.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| X77 | X77|Proteinase Inhibitor|For Research Use | X77 is a non-covalent inhibitor for coronavirus main protease (3CLpro) research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

The hydrolytic degradation of PLA, driven by ester bond hydrolysis and autocatalytic effects, can be strategically modulated through various chemical modifications to achieve desired performance profiles. Cross-linked and chain-extended systems demonstrate enhanced resistance to hydrolysis by reducing autocatalytic sites and restricting chain mobility, making them suitable for applications requiring extended functional lifetimes. Conversely, additive-containing systems with controlled catalytic agents enable accelerated degradation, beneficial for reducing environmental persistence. The experimental methodologies and comparative data presented herein provide researchers and drug development professionals with practical tools for designing PLA-based materials with tailored degradation characteristics. As PLA continues to gain prominence across packaging, biomedical, and agricultural sectors, understanding and controlling these fundamental degradation mechanisms remains paramount for optimizing material performance while managing environmental impact.

The manipulation of cross-link density is a fundamental strategy in polymer science for tailoring the properties of materials to meet specific application requirements. Within the context of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) research, understanding the relationship between cross-link density and material performance is crucial for advancing its use in biomedical applications, drug delivery systems, and sustainable materials. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how different cross-linking methods and densities influence the thermal behavior, mechanical performance, and degradation characteristics of PLA-based materials, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform their material design decisions.

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Linking Methods and Properties

The cross-linking of PLA can be achieved through various methods, each resulting in different network structures and property enhancements. The following sections compare the primary approaches, their resulting material properties, and their implications for practical applications.

Cross-Linking Methodologies and Their Mechanisms

Chemical Cross-Linking involves creating covalent bonds between polymer chains using cross-linking agents or functionalized polymers. One approach utilizes carbodiimide chemistry to couple 4-arm star PLLA prepolymers, creating networks with well-defined molecular weight between crosslinks (Mc) [7]. Another chemical method involves synthesizing crosslinkable poly(lactic acid-co-glycidyl methacrylate) copolymers through ring-opening polymerization, where the incorporated glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) content significantly affects the physical and thermal properties of the resulting copolymers [21].

High-Energy Radiation Cross-Linking employs electron beam or gamma irradiation to generate radicals on polymer chains, which subsequently form cross-links. PLA predominantly undergoes chain scission under ionizing radiation; however, cross-linking can be promoted by adding polyfunctional monomers such as triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC), trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA), or trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TMPTMA) [1]. The cross-linking density can be precisely adjusted by varying the TAIC content and absorbed irradiation dose [22].

Photo-Cross-Linking represents a practical method for curing PLA-based copolymers under mild conditions. The crosslinking of P(LLA-co-GMA) copolymers via this method was shown to be almost complete within 2 minutes, achieving a gel content of 96% [21].

Correlation Between Cross-Link Density and Material Properties

The molecular weight between crosslinks (Mc) is a critical parameter determining the physical properties of cross-linked PLA. Research demonstrates that Mc values significantly influence degradation behavior, with low Mc (1400 g/mol) networks confining degradation to the outer surface, while higher Mc (3500 g/mol) networks exhibit degradation in a 400 μm layer at the surface [7].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cross-Linked PLA Systems

| Cross-Linking Method | Cross-Link Agent/Density | Mechanical Performance | Thermal Properties | Degradation Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical (Carbodiimide) | Mc = 1400 g/mol | Increased tensile strength vs. linear analogues [7] | Amorphous structure [7] | Surface erosion mechanism [7] |

| Chemical (GMA copolymer) | 19.2 mol% GMA | Compressive stress: 25.5 MPa [21] | Varies from semi-crystalline to amorphous [21] | Thermo-crosslinking at 120°C [21] |

| γ-Ray Irradiation | 10 wt% TAIC, 30 kGy | Shape recovery ratio: 99.5% [22] | Tunable Tg and Tm [22] | Retarded degradation [1] |

| Electron Beam | 3% TAIC, 30-50 kGy | Rubbery and stable above Tm [1] | Improved heat stability [1] | Considerably retarded [1] |

The mechanical properties of cross-linked PLA systems show significant improvements over linear PLA. Chemically cross-linked rigid polyester materials, such as PLLA networks, have been shown to possess comparable or even enhanced tensile strength to their high molecular weight semi-crystalline linear analogues [7]. In radiation cross-linking, the addition of TAIC and appropriate irradiation doses produces materials that become harder and more brittle at low temperatures but remain rubbery, soft, and stable at higher temperatures, even over the melting point (Tm) [1].

The thermal properties and shape memory performance of cross-linked PLA can be precisely tuned through cross-link density control. The incorporation of crosslinking points significantly suppresses cold crystallization and prevents irreversible chain slippage during deformation, resulting in exceptionally high shape recovery ratios (99.5%) and good cycle stability (maintaining 97.9% after three cycles) [22]. These cross-linked systems can be designed as triple-shape memory polymers, utilizing both the glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm) as switching transitions [22].

The degradation behavior of cross-linked PLA networks differs significantly from linear PLA, transitioning from bulk degradation to a surface erosion mechanism. This shift is particularly evident in networks with low Mc values, where the degradation is confined to the outer surface [7]. The crosslinking process generally leads to a decrease in degradability, which can be advantageous for applications requiring longer implant destruction times or extended drug delivery profiles [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of Cross-Linked PLA Networks

Chemical Cross-Linking via Carbodiimide Chemistry:

- Synthesize 4-arm hydroxy-terminated star PLLA prepolymers with controlled molecular weights.

- Employ carbodiimide-mediated coupling (using N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N'-ethyl carbodiimide hydrochloride, EDC) to connect the star polymers through succinic anhydride.

- Control the Mc value (1400-3500 g/mol) by adjusting the molecular weight of the prepolymers and the stoichiometry of the reaction.

- Purify the resulting networks to remove any sol fraction and characterize the gel content [7].

Radiation Cross-Linking with TAIC:

- Dry PLA pellets thoroughly in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 12 hours to prevent hydrolysis.

- Premix PLA with triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) in a Haake mixer at 190°C with a rotation speed of 50 rpm for 10 minutes to form a homogeneous blend.

- Prepare TAIC weight fractions typically ranging from 1% to 10%.

- Hot-press the blends at 190°C under a pressure of 10 MPa to obtain films with uniform thickness (e.g., 300 μm).

- Vacuum seal the specimens and irradiate using a γ-ray source (e.g., 60Co) with doses typically around 30 kGy at room temperature [22].

Characterization Techniques

Gel Content Measurement:

- Weigh the initial dry sample (mâ‚€).

- Immerse the sample in chloroform at room temperature for 48 hours to extract the sol fraction.

- Remove the sample and dry it to constant weight (m₄₈).

- Calculate the gel content using the formula: Gel content = [(m₄₈ - m₀)/m₀] × 100% [22].

Thermal Analysis:

- Perform Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) with a heating rate of 10°C/min from 0°C to 200°C under nitrogen atmosphere.

- Calculate the crystallinity (Xc) using the equation: Xc = (ΔHm - ΔHcc)/ΔHₘⰠ× 100%, where ΔHm is the melting enthalpy, ΔHcc is the cold crystallization enthalpy, and ΔHₘⰠis the standard melting enthalpy for perfectly crystalline PLLA (93 J/g) [22].

- Utilize Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) to determine the glass transition temperature (Tg) at an oscillation frequency of 5 Hz.

Mechanical Property Assessment:

- For shape memory performance, conduct uniaxial stretching experiments using rectangular specimens.

- Stretch specimens until strain reaches 100% in hot water (80°C), then rapidly cool in cool water (25°C) for 10 seconds to fix the temporary shape.

- Measure shape recovery by reheating the deformed specimens and quantifying the recovery ratio [22].

- Evaluate compressive strength using universal testing machines with constant head speed (e.g., 6 mm/min for hydrogels) [23].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for PLA Cross-Linking

| Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Triallyl Isocyanurate (TAIC) | Polyfunctional cross-linking monomer | Radiation-induced cross-linking [1] [22] |

| Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) | Reactive comonomer for copolymer synthesis | Chemical cross-linking via epoxy groups [21] |

| Carbodiimide (EDC) | Coupling agent for carboxyl and hydroxyl groups | Chemical cross-linking of star polymers [7] |

| Trimethylolpropane Triacrylate (TMPTA) | Polyfunctional cross-linking monomer | Electron-beam induced cross-linking [1] |

| Succinic Anhydride | Chain extender/coupling agent | Carbodiimide-mediated network formation [7] |

Cross-Linking Pathways and Property Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between cross-linking methods, structural parameters, and the resulting material properties in PLA systems:

Cross-Linking Pathways and Property Relationships in PLA: This diagram illustrates how different cross-linking methods influence structural parameters and ultimately determine the final properties of PLA-based materials. The pathways show the progression from method selection to parameter control and resulting performance characteristics.

The systematic correlation between cross-link density and material performance in PLA systems reveals fundamental structure-property relationships that enable precise tuning of thermal, mechanical, and degradation characteristics. Chemical cross-linking methods provide control over network architecture through molecular design, while radiation and photo-cross-linking offer efficient processing routes with spatial and temporal control. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that lower Mc values generally enhance thermal stability, modify degradation from bulk erosion to surface erosion, and improve shape memory performance. These relationships provide researchers with a framework for designing PLA-based materials tailored to specific application requirements in biomedical devices, drug delivery systems, and sustainable materials. Future research directions should focus on developing more precise methods for controlling cross-link density distribution and understanding long-term property evolution during degradation.

Poly(lactic acid) (PLA) has emerged as a leading biodegradable and biobased polymer for applications ranging from biomedical devices to sustainable packaging. However, its widespread adoption is limited by inherent drawbacks, including insufficient heat resistance and poor shape stability at elevated temperatures. Overcoming these limitations is crucial for meeting the performance requirements in demanding fields such as drug delivery and high-temperature packaging. Cross-linking strategies present a powerful approach to enhance PLA's mechanical and thermal properties. Among these, stereocomplexation—the formation of a crystalline structure between poly(L-lactide) (PLLA) and poly(D-lactide) (PDLA)—has garnered significant attention for its ability to substantially improve thermal stability without compromising biocompatibility. This guide provides a comparative analysis of stereocomplex-based cross-linking against other cross-linking methodologies, evaluating their respective impacts on crystallization behavior, heat resistance, and material degradation.

Comparative Analysis of Cross-Linking Strategies for PLA

PLA cross-linking is primarily achieved through three distinct mechanisms: stereocomplexation, chemical cross-linking, and high-energy irradiation. The following sections and comparative table detail the properties and performance of materials produced by each method.

Table 1: Comparison of Cross-Linking Methods for PLA-Based Systems

| Cross-Linking Method | Key Components / Conditions | Melting Temp (Tm) / Heat Resistance | Mechanical Properties | Degradation Resistance | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereocomplexation | PLLA + PDLA (Linear or Star-shaped) | ~220-230°C (for Sc crystal) [24]; Vicat Softening Temp: ~64.9°C (at optimal crystallization) [5] | Toughness increased by 40-47x; Elongation at break increased by 35-43x [24] | Strong resistance to hydrolysis [25]; Higher crystallinity decelerates enzymatic degradation [25] | Microwavable packaging [24]; Drug delivery systems [25] |

| Chemical Cross-Linking | EGDMA; PAPI cross-linker [26] [27] | Improved shape stability | Tensile strength increased by 85.5% in BF/SC-PLA composites [27] | N/A | Dual-sensitive hydrogels (temp/pH) [26]; Bamboo fiber composites [27] |

| High-Energy Irradiation | Electron beam/Gamma rays; Cross-linking co-agents (e.g., TAIC) [1] | Rubber-like stability above Tm [1] | Becomes harder and more brittle at low temps [1] | Degradation considerably retarded [1] | Medical implants; Daily-use items [1] |

The data reveals that stereocomplexation uniquely enhances heat resistance by elevating the melting temperature of the crystalline regions. Furthermore, the combination of stereocomplexation with chemical cross-linkers in dual-cross-linked systems leads to synergistic improvements in mechanical strength, as evidenced by the significant increase in tensile strength for bamboo fiber-reinforced composites [27].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Forming Stereocomplex Crystals (Sc-PLA)

Objective: To create a stereocomplex PLA structure with enhanced melting temperature and thermal stability.

- Materials: PLLA and PDLA (either linear or star-shaped architectures).

- Procedure:

- Dissolution: Dissolve PLLA and PDLA in a 1:1 mass ratio in a mutual solvent such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) with a typical concentration of 1.0 mg/mL [25].

- Self-Assembly: Allow the solution to stand for a period of 7 days to facilitate the self-assembly and formation of the stereocomplex crystalline structure [25].

- Processing: The solution can be cast into films, or the solid blend can be processed via melt extrusion followed by thermoforming into final products like packaging trays [24].

- Key Characterization Techniques:

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): To identify the melting peak of the stereocomplex crystal (~220-230°C), which is distinct from the homopolymer crystal melting peak (~180°C) [24].

- Wide-Angle X-Ray Diffraction (WAXD): To confirm the formation of the stereocomplex crystal structure, which exhibits a characteristic diffraction pattern different from that of homo-crystals [24].

Synthesizing Dual-Cross-Linked Hydrogels

Objective: To prepare a hydrogel with superior mechanical properties and stability by combining physical (stereocomplex) and chemical cross-links.

- Materials: HEMA-terminated PLLA and PDLA macromonomers (HEMA-PLLA/PDLA), temperature-sensitive monomers (MEOâ‚‚MA, OEGMA), pH-sensitive monomer (DEAEMA), chemical cross-linker (ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, EGDMA), and initiator (AIBN) [26].

- Procedure:

- Physical Cross-linking: Dissolve HEMA-PLLA and HEMA-PDLA in THF, subject to low-temperature ultrasonication for 30 minutes to form a stereocomplex physical network, and then evaporate the solvent [26].

- Chemical Cross-linking: Combine the stereocomplexed macromonomers with MEOâ‚‚MA, OEGMA, DEAEMA, EGDMA, and AIBN. Purge the mixture with nitrogen to create an inert atmosphere.

- Polymerization: Seal the reaction vessel and place it in an oil bath at 70°C for 1 hour to initiate free radical polymerization, forming the permanent chemical network [26].

- Key Characterization Techniques:

- Swelling Studies: To evaluate temperature and pH sensitivity by measuring equilibrium swelling ratios in different buffers and temperatures.

- Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA): To assess the mechanical robustness and viscoelastic properties of the dual-cross-linked gel compared to solely physically or chemically cross-linked gels [26].

Cross-Linking via High-Energy Irradiation

Objective: To induce cross-linking in pristine PLA or its blends, improving thermal stability and retarding degradation.

- Materials: PLA polymer and a polyfunctional monomer, such as triallyl isocyanurate (TAIC) or trimethylolpropane trimethacrylate (TMPTMA) [1].

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the PLA with 1-3% of the cross-linking co-agent (e.g., TAIC) to facilitate network formation over chain scission [1].

- Irradiation: Expose the sample to a controlled dose of high-energy radiation, typically an electron beam at doses of 30–50 kGy [1].

- Post-Processing: The cross-linked material can be processed into films or molded parts.

- Key Characterization Techniques:

- Gel Content Analysis: To determine the fraction of insoluble cross-linked material, indicating the efficiency of network formation [1].

- Thermal Analysis (DSC/TGA): To evaluate the enhancement in heat stability and thermal degradation resistance.

Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making pathway for selecting and implementing a cross-linking method to achieve target material properties, based on the experimental protocols discussed.

Diagram 1: Pathway for Designing Cross-Linked PLA Systems. This workflow guides the selection of primary and complementary cross-linking strategies based on target application requirements.

The experimental workflow for creating a dual-cross-linked system, which yields some of the most synergistic property enhancements, is detailed below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Dual-Cross-Linked Hydrogel Synthesis. This protocol combines physical stereocomplexation and chemical covalent bonding to create networks with superior properties [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research and development in cross-linked PLA systems require specific, high-purity reagents and materials. The following table lists key components and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for PLA Cross-Linking Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Typical Usage & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PLLA & PDLA (Linear and Star-shaped) | Enantiomeric polymers that form the stereocomplex crystal backbone. | Use high molecular weight grades for mechanical strength; star-shaped architectures enhance toughness and processability [24]. |

| Triallyl Isocyanurate (TAIC) | Polyfunctional monomer used as a cross-linking co-agent in irradiation. | Applied at 1-3% concentration to promote cross-linking over chain scission during electron beam irradiation [1]. |

| Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Chemical cross-linker for creating covalent networks in hydrogels. | Used in free radical polymerization to form permanent, stable chemical bonds within the polymer matrix [26]. |

| Polyaryl Polymethylene Isocyanate (PAPI) | Cross-linker for composites, forming bonds between fillers and polymer matrix. | Improves interfacial adhesion in biomass-filled composites (e.g., bamboo fiber/SC-PLA), significantly boosting tensile strength [27]. |

| Tin(II) Octoate | Catalyst for the ring-opening polymerization of lactide monomers. | Essential for synthesizing PLA macromonomers and star-shaped polymers with controlled architectures [24]. |

| Proteinase K | Enzyme used for in vitro enzymatic degradation studies. | Preferentially hydrolyzes PLLA; used to evaluate and compare degradation rates of different crystalline forms and cross-linked systems [25]. |

| AP39 | AP39|Mitochondria-Targeted H₂S Donor|RUO | |

| ErSO | ErSO|Anticancer Research Compound|RUO | ErSO is a small molecule for research use only (RUO), not for human consumption. It induces tumor regression via a-UPR hyperactivation. Explore its applications. |

This comparison guide demonstrates that stereocomplexation is a uniquely powerful strategy for enhancing the heat resistance and crystalline stability of PLA, primarily through the formation of high-melting-point stereocomplex crystals. When integrated with other methods—such as chemical cross-linking for superior mechanical strength in composites and hydrogels or irradiation for sterilization and stability—researchers can tailor the properties of PLA-based materials to meet specific and demanding application requirements. The choice of method is not mutually exclusive; the most advanced material systems often leverage the synergistic effects of multiple cross-linking mechanisms. The provided experimental protocols and toolkit offer a foundation for researchers in drug development and material science to design and implement these sophisticated cross-linked systems effectively.

Synthesis and Processing: Advanced Methodologies for Cross-Linked PLA in Biomedical and Industrial Applications

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a leading biodegradable and bio-based aliphatic polyester, derived from renewable resources like corn starch, and is recognized as a key material for sustainable plastic solutions. However, its widespread application is hindered by inherent drawbacks, including inadequate impact resistance, brittleness, and poor heat resistance, with a heat resistance temperature typically around 60°C [27]. These limitations restrict its use in demanding applications such as automotive components, durable goods, and thermal insulation. Among various modification strategies, in-situ cross-linking has emerged as a powerful technique to overcome these challenges. This process involves creating a network structure within the polymer blend during processing, significantly enhancing its melt strength, compatibility, and ultimate performance [28] [1].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of prominent in-situ cross-linking techniques for PLA/polymer blends, focusing on their efficacy in improving impact resistance and thermal insulation. We objectively compare the performance of different blend systems and cross-linking strategies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to serve researchers and scientists in selecting and developing optimal material solutions.

Performance Comparison of Cross-Linked PLA Blends

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for various PLA blends modified with in-situ cross-linking, providing a direct comparison of their effectiveness.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cross-Linked PLA Blends

| PLA Blend System & Cross-Linking Strategy | Key Performance Improvements | Impact Strength | Thermal Conductivity (mW/m·K) | Tensile/Flexural Strength | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/P4HB with In-situ Cross-Linking [28] | Transition from open-cell to closed-cell foam structure; Enhanced heat stability. | Specific impact strength: 26.17 kJ·mâ»Â²/(g·cmâ»Â³) | 31.5 | N/P | [28] |

| PLA/PBAT with Dynamically Cross-Linked ESO (VEC) [29] | Improved compatibility and toughness; Excellent processability. | Significantly improved (specific data in Table 2) | N/P | Maintained or improved | [29] |

| PLA/PBAT with MA Grafting (PBAT-MA) [30] | Enhanced interfacial compatibility and toughness. | 333.9 kJ/m² (+917.3% vs. unmodified) | N/P | Fracture elongation: 358.1% (+450.4%) | [30] |

| Bamboo Fiber/SC-PLA with PAPI Cross-Linking [27] | High heat resistance and improved mechanical properties. | N/P | N/P | Tensile strength: 34.7 MPa (+85.5%) | [27] |

| PLA Cross-Linked via High-Energy Irradiation & TAIC [1] | Improved heat stability and mechanical properties; Retarded degradation. | Becomes harder and more brittle at low temperatures, but soft and stable at higher temperatures. | N/P | Enhanced | [1] |

Abbreviations: N/P - Not Provided in the cited source; P4HB - Poly(4-hydroxybutyrate); PBAT - Poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate); ESO - Epoxidized Soybean Oil; VEC - Vulcanized ESO and Citric Acid; MA - Maleic Anhydride; SC-PLA - Stereo-complex PLA; PAPI - Polyaryl Polymethylene Isocyanate; TAIC - Triallyl Isocyanurate.

The data demonstrates that different cross-linking strategies yield distinct performance advantages. The PLA/P4HB foam system shows exceptional promise for thermal insulation applications due to its very low thermal conductivity [28]. Conversely, for impact resistance, the PLA/PBAT-MA system exhibits a dramatic, order-of-magnitude increase in impact strength, making it suitable for high-toughness applications [30].

Detailed Experimental Data and Methodology

Impact Resistance and Toughness

The following table provides quantitative data on the mechanical enhancements achieved through specific cross-linking protocols.

Table 2: Enhancement of Impact Resistance and Toughness

| Blend System | Compatibilizer/ Cross-Linking Agent | Key Processing Parameters | Resulting Mechanical Properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA/PBAT | Epoxidized Soybean Oil (ESO) & Anhydrous Citric Acid (CA) | Dynamic cross-linking; VEC R-value of 0.1 | Significantly improved toughness and impact resistance. | [29] |

| PLA/PBAT | Maleic Anhydride (MA) | Melt-grafting; MA: 2 wt%, BPO initiator: 1 wt%; Twin-screw extruder at 125-135°C | Impact strength: 333.9 kJ/m² (917.3% increase); Fracture elongation: 358.1% (450.4% increase). | [30] |

| Bamboo Fiber/ SC-PLA | Polyaryl Polymethylene Isocyanate (PAPI) | Cross-linking during extrusion (200-220°C) and injection molding (220°C) | Tensile strength: 34.7 MPa (85.5% increase vs. unmodified composite). | [27] |

Thermal Insulation and Stability

In-situ cross-linking significantly influences the thermal properties of PLA blends, particularly by enhancing thermal stability and enabling the formation of insulating foam structures.

Foam Structure and Thermal Insulation: An in-situ cross-linking strategy applied to PLA/P4HB blends drastically improved their foaming behavior. The technique enhanced melt strength and crystallization behavior, causing the foam to transition from an open-cell to a closed-cell structure. This resulted in a volume expansion ratio (VER) of 35.4 and a cell density of 2.0 × 10â· cells/cm³, which are 16.1-fold and 9.1-fold increases, respectively, compared to the unmodified foam. This fine closed-cell structure endowed the foam with excellent thermal insulation properties, achieving a thermal conductivity as low as 31.5 mW/m·K and a thermal diffusivity of 8.1 × 10â»â· m²/s [28].

Heat Resistance: For rigid composites, cross-linking improves heat resistance. Using a cross-linking agent like PAPI in Bamboo Fiber/Stereo-complex PLA (SC-PLA) composites creates a robust network that enhances the material's ability to withstand higher temperatures, which is crucial for applications like heat-resistant food packaging [27]. Furthermore, PLA cross-linked with high-energy irradiation in the presence of co-agents like TAIC exhibits much-improved heat stability, remaining soft and stable at temperatures even above its melting point [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: In-situ Cross-Linking for PLA/P4HB Foams

This protocol is designed to produce closed-cell foams with superior impact resistance and thermal insulation [28].

- Primary Materials: Polylactic acid (PLA), Poly(4-hydroxybutyrate) (P4HB).

- Cross-Linking Strategy: Employ an in-situ cross-linking agent to enhance compatibility between PLA and P4HB.

- Procedure:

- Melt Blending: Blend PLA and P4HB with the cross-linking agent in a melt mixer.

- Supercritical Foaming: Process the modified blend using a supercritical foaming technique.

- Analysis: Characterize the foam morphology (cell density, volume expansion ratio) using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Measure thermal conductivity using a thermal analyzer and impact strength via impact testing.

Workflow for PLA/P4HB Foam Cross-Linking

Protocol 2: Dynamic Cross-Linking of PLA/PBAT with ESO

This method uses dynamic covalent chemistry to toughen PLA/PBAT blends while maintaining processability [29].

- Primary Materials: PLA, PBAT, Epoxidized Soybean Oil (ESO), Anhydrous Citric Acid (CA), Zinc Acetate (Zn(OAc)â‚‚) catalyst.

- Cross-Linking Strategy: Form a dynamic covalent adaptable network (VEC) between ESO and CA via ring-opening and reversible ester exchange reactions.

- Procedure:

- Mixing: Melt-blend PLA, PBAT, ESO, and CA.

- Dynamic Vulcanization: In-situ formation of the VEC cross-linked network within the blend during processing.

- Compatibilization: The VEC network acts as an intermediate phase to improve PLA/PBAT compatibility.

- Testing: Evaluate mechanical properties (tensile, impact) and thermal stability (DSC, TGA).

Protocol 3: Reactive Melt-Grafting of MA onto PBAT

This protocol focuses on improving interfacial compatibility in PLA/PBAT blends by grafting maleic anhydride onto PBAT [30].

- Primary Materials: PBAT, Maleic Anhydride (MA), Benzoyl Peroxide (BPO) initiator.

- Grafting Strategy: Free radical-induced grafting of MA onto the PBAT chain.

- Procedure:

- Drying: Dry PBAT at 70°C for 12 hours.

- Reactive Extrusion: Use a twin-screw extruder to blend PBAT, MA (1-5 wt%), and BPO (1 wt%). Typical extrusion temperatures are 125-135°C, with a screw speed of 60 rpm.

- Blending with PLA: Melt-blend the resulting PBAT-MA graft copolymer with PLA.

- Analysis: Confirm grafting via FTIR. Test mechanical properties and analyze microstructure morphology (SEM).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for In-situ Cross-Linking of PLA Blends

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Cross-Linking Process | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Maleic Anhydride (MA) [30] | Monomer for grafting; enhances interfacial compatibility by reacting with terminal hydroxyl groups of polyesters. | Reactive compatibilizer in PLA/PBAT blends. |

| Benzoyl Peroxide (BPO) [30] | Free radical initiator to kick-start the grafting reaction of MA onto polymer chains. | Initiator for melt-grafting reactions. |

| Epoxidized Soybean Oil (ESO) [29] | Bio-based polyepoxide; undergoes ring-opening with acids to form cross-linked networks. | Dynamic cross-linking agent in PLA/PBAT blends. |

| Anhydrous Citric Acid (CA) [29] | Multi-functional acid; reacts with epoxy groups of ESO and catalyzes dynamic ester exchange reactions. | Co-agent and catalyst for dynamic networks. |

| Triallyl Isocyanurate (TAIC) [1] | Polyfunctional monomer; acts as a cross-linking promoter under high-energy irradiation. | Co-agent for radiation-induced cross-linking. |

| Polyaryl Polymethylene Isocyanate (PAPI) [27] | Multi-functional isocyanate; forms urethane linkages with hydroxyl groups, creating cross-links. | Cross-linker for biomass-filled PLA composites. |

| NH-3 | NH-3, CAS:447415-26-1, MF:C28H27NO6, MW:473.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PGPC | PGPC, MF:C29H56NO10P, MW:609.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Cross-Linking Effects on Crystallization and Degradation

In-situ cross-linking induces profound changes in PLA's crystallization behavior and degradation profile, which are critical within the broader thesis of understanding structure-property relationships.

Effects on Crystallization: Cross-linking can directly influence nucleation and crystal growth. In some systems, the cross-linked network can restrict chain mobility, potentially slowing down the overall crystallization rate [31]. However, specific strategies can counteract this. For instance, the formation of stereocomplex (SC) crystallites in blends of PLLA and PDLA can act as highly effective nucleating agents, accelerating the crystallization of PLLA homo-crystals and raising the melting temperature, thereby enhancing heat resistance [27] [31]. Furthermore, in PLA/P4HB blends, cross-linking was shown to improve crystallization behavior, providing additional nucleation sites for foaming [28].

Effects on Degradation: Cross-linking creates a three-dimensional network that slows down the permeation of water and the progression of hydrolysis through the polymer matrix. Consequently, the degradation rate of cross-linked PLA is considerably retarded compared to its linear counterpart [1]. This is a crucial consideration for both biomedical applications, where longer implantation times may be desired, and for durable goods where extended service life is needed. The degradation profile can be tuned by the cross-linking density, allowing researchers to design materials with tailored lifespans [1].

Cross-Link Effects on PLA Properties

In-situ cross-linking is a versatile and powerful strategy for advancing the performance of PLA blends, directly addressing their key weaknesses in impact resistance and thermal management. The comparative data presented in this guide reveals that the choice of blend partner and cross-linking chemistry dictates the final property profile. PLA/PBAT systems modified with MA or ESO are unparalleled for achieving extreme toughness, making them suitable for applications requiring high impact strength. Conversely, PLA/P4HB blends with in-situ cross-linking are ideal for creating high-performance, biodegradable thermal insulation foams. As research progresses, the refinement of these techniques, particularly using bio-derived reagents and dynamic covalent chemistry, will further expand the applications of sustainable PLA-based materials in demanding technological and industrial fields.