Flow Cytometry vs. Fluorescence Microscopy for Cell Viability: A Definitive Guide for Biomaterial and Drug Development Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of flow cytometry (FCM) and fluorescence microscopy (FM) for cell viability assessment, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Flow Cytometry vs. Fluorescence Microscopy for Cell Viability: A Definitive Guide for Biomaterial and Drug Development Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of flow cytometry (FCM) and fluorescence microscopy (FM) for cell viability assessment, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of each technique, detailing their specific methodologies and staining protocols through recent application case studies. The content offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies and presents a rigorous, validation-focused comparison based on a seminal 2025 study. By synthesizing performance data on sensitivity, resolution, and throughput, this guide empowers scientists to select the most appropriate, robust, and quantitative method for their specific research context, particularly in challenging systems like particulate biomaterials.

Core Principles: How Flow Cytometry and Fluorescence Microscopy Work

The Fundamental Operating Principle of Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry represents a cornerstone technology in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, enabling rapid, multiparameter analysis of individual cells in suspension. Within the context of cell viability assessment, this technique provides unparalleled quantitative precision for distinguishing between live, apoptotic, and dead cell populations within heterogeneous samples. As researchers and drug development professionals increasingly require sophisticated viability metrics beyond simple live/dead dichotomies, understanding the fundamental operating principles of flow cytometry becomes essential for selecting appropriate methodologies and interpreting experimental data accurately.

This guide examines the core technological principles of flow cytometry and objectively compares its performance with fluorescence microscopy for cell viability assessment, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Core Operating Principles

System Components and Their Functions

Flow cytometers operate based on integrated systems working in synchrony:

Fluidics System: Hydrodynamically focuses cells into a single-file stream, ensuring that only one cell at a time passes through the laser interrogation point. This precise cellular alignment is critical for accurate single-cell measurements [1] [2].

Optics System: Comprises lasers as light sources and optical filters that separate specific wavelength ranges. As cells pass through the laser beam, they scatter light and fluorescent probes emit light at characteristic wavelengths [3] [2].

Electronics System: Detects light signals using photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or other detectors, converts them into digital data, and processes this information for analysis. Modern systems can process thousands of cells per second, generating statistically robust datasets [3] [2].

Signal Detection and Data Generation

As each cell passes through the laser beam, two types of optical signals are generated:

- Light Scatter: Forward-scattered light (FSC) correlates with cell size, while side-scattered light (SSC) indicates cellular complexity/granularity [2].

- Fluorescence Emission: Fluorescently-labeled antibodies or dyes bound to cellular components emit light at specific wavelengths when excited by lasers, enabling quantification of specific markers [2].

The detection system in conventional flow cytometers utilizes optical filters (dichroic mirrors and bandpass filters) to separate and direct light emitted by fluorophores to appropriate detectors. Each detector is tuned to a narrow wavelength band approximating the emission peak of specific fluorophores, implementing a "one detector–one fluorophore" approach [3].

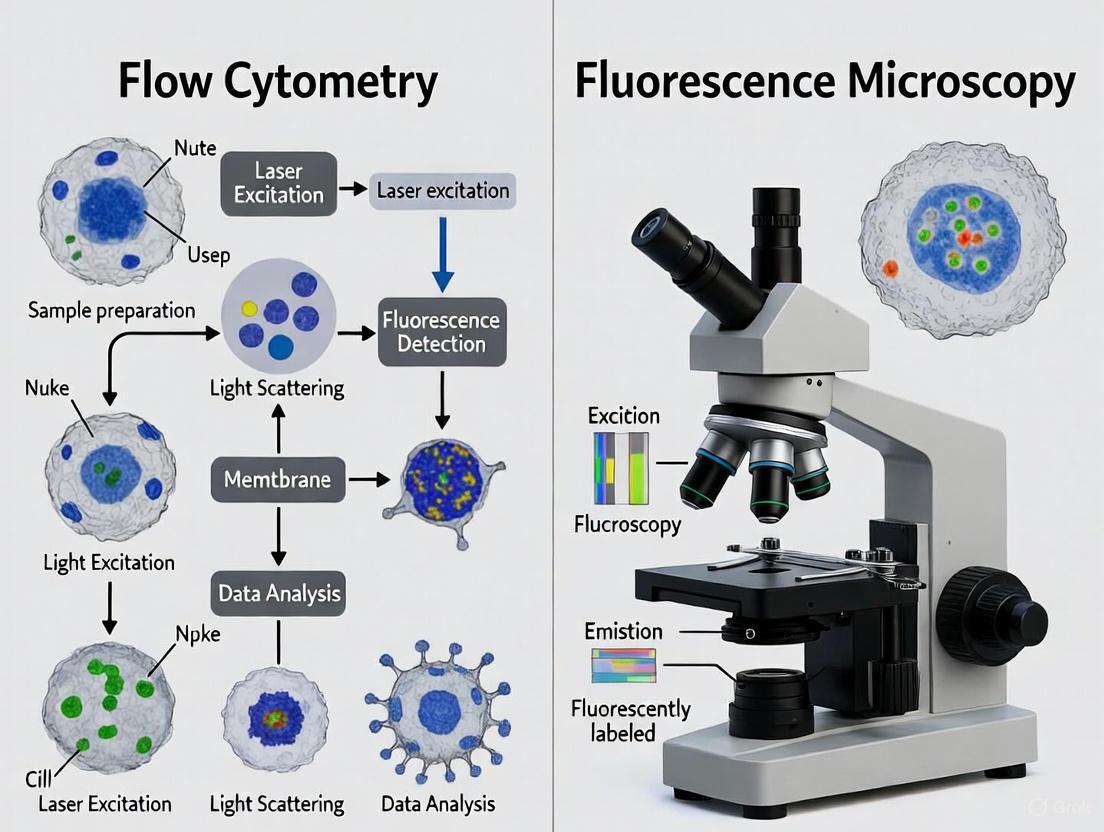

Figure 1: Flow Cytometry Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from sample introduction to data analysis in flow cytometry.

Comparative Analysis: Flow Cytometry vs. Fluorescence Microscopy

Technical Comparison

Table 1: Technical comparison between flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy for cell viability assessment

| Feature | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (10,000+ events/second) [1] | Low to medium (manual counting) to automated |

| Data Type | Quantitative fluorescence intensity [1] | Quantitative intensity with morphological context [1] |

| Information Gained | Population statistics, protein expression levels [1] | Morphology, subcellular localization, cell-cell interactions [1] |

| Spatial Context | Lost [1] | Preserved [1] |

| Multiparametric Capacity | High (up to 40+ parameters with spectral systems) [3] | Limited by filter cubes and fluorophore overlap |

| Statistical Power | Excellent for large populations [2] | Limited without automated systems |

Performance in Cell Viability Assessment

Table 2: Comparison of cell viability assessment capabilities between flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy

| Assessment Aspect | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Viability Staining | Multiparametric staining (e.g., Hoechst, DiIC1, Annexin V-FITC, PI) [4] | Typically FDA/PI or calcein AM/ethidium homodimer [4] |

| Cell Death Discrimination | Can distinguish early apoptosis, late apoptosis, and necrosis [4] | Generally dichotomizes into live/dead [4] |

| Sensitivity | High (detected 0.2% viability with BG particles <38μm) [4] | Lower (detected 9% viability in same conditions) [4] |

| Correlation Between Methods | Strong correlation (r=0.94) with microscopy data [4] | Strong correlation (r=0.94) with flow data [4] |

| Measurement Agreement | Average difference of 1.7-2.7% compared to microscopy [5] | Average difference of 1.7-2.7% compared to flow [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Viability Assessment

Multiparametric Viability Staining Protocol for Flow Cytometry

Application: Detailed assessment of cell health status, discriminating between viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations [4] [6].

Reagents:

- Hoechst 33342 (nuclear stain)

- DiIC1 (mitochondrial membrane potential indicator)

- Annexin V-FITC (phosphatidylserine exposure detection)

- Propidium Iodide (PI) or 7-AAD (membrane integrity assessment) [4] [6]

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells and wash with cold PBS. Adjust concentration to 1×10ⶠcells/mL in binding buffer.

- Staining:

- Add Hoechst 33342 (1 μg/mL) and incubate 15 minutes at 37°C

- Add DiIC1 (20 nM) and incubate 15 minutes at 37°C

- Add Annexin V-FITC (5 μL/test) and incubate 15 minutes at room temperature in darkness

- Add PI or 7-AAD (5 μL/test) 5 minutes before acquisition

- Data Acquisition: Analyze samples immediately using flow cytometer with appropriate laser configurations [6].

- Analysis:

- Viable cells: Hoechstâº, DiIC1âº, Annexin Vâ», PIâ»

- Early apoptotic: Hoechstâº, DiIC1âº/â», Annexin Vâº, PIâ»

- Late apoptotic: Hoechstâº, DiIC1â», Annexin Vâº, PIâº

- Necrotic: Hoechstâº, DiIC1â», Annexin Vâ», PI⺠[6]

Comparative Viability Assessment Protocol

Application: Direct comparison of flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy for viability assessment [4] [5].

Reagents:

- Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) or calcein AM (viable cell stain)

- Propidium iodide (PI) or ethidium homodimer-1 (dead cell stain) [4] [5]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare identical cell samples for both analysis methods.

- Staining: Incubate cells with FDA/calcein AM (1-5 μM) and PI/ethidium homodimer-1 (1-5 μg/mL) for 15-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Flow Cytometry Analysis:

- Analyze 10,000-50,000 events per sample

- Use 488nm laser for excitation

- Detect FDA/calcein AM fluorescence at 530/30nm

- Detect PI/ethidium homodimer-1 fluorescence at 610/20nm [4]

- Fluorescence Microscopy Analysis:

- Image multiple fields (minimum 5) with 10-20× objective

- Count at least 1,000 cells total for statistical significance

- Calculate viability as: (FDA⺠cells)/(total cells) × 100 [5]

- Data Correlation: Compare viability percentages between methods using linear regression analysis [4] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents for cell viability assessment in flow cytometry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital Dyes | FDA, calcein AM | Esterase activity in viable cells | Cell-permeable, converted to fluorescent product in live cells [4] |

| Membrane Integrity Indicators | Propidium iodide, 7-AAD, ethidium homodimer | DNA binding in membrane-compromised cells | Cell-impermeable, only enter dead cells [4] [7] |

| Apoptosis Detectors | Annexin V conjugates | Binds phosphatidylserine exposed on apoptotic cells | Requires calcium-containing buffer [6] |

| Mitochondrial Function Probes | DiIC1, DiOC₆(3) | Monitor mitochondrial membrane potential | Loss of signal indicates early apoptosis [6] |

| Nuclear Stains | Hoechst 33342, DAPI | Identify nucleated cells | Distinguish cells from debris [6] |

Advanced Technological Developments

Spectral Flow Cytometry

Spectral flow cytometry represents a significant advancement over conventional systems. Instead of using optical filters to direct specific wavelength ranges to individual detectors, spectral cytometers collect the entire emission spectrum of each fluorophore across a wide wavelength range (typically using 32-64 detection channels) [3]. This is achieved through using a prism or diffraction grating to scatter emitted light, which is captured by an array of highly sensitive detectors [3].

Advantages for Viability Assessment:

- Enables resolution of more fluorophores with overlapping spectra

- Improves sensitivity for detecting low-abundance markers

- Simplifies panel design for complex multiparametric viability panels [3]

Imaging Flow Cytometry

Imaging flow cytometry combines the high-throughput capabilities of conventional flow cytometry with the morphological analysis strengths of microscopy. Recent advancements have pushed throughput boundaries, with systems now capable of processing over 1,000,000 events per second while capturing high-resolution images of individual cells [8].

Advantages for Viability Assessment:

- Provides morphological confirmation of apoptotic features (membrane blebbing, nuclear condensation)

- Enables analysis of cell-cell interactions in viability contexts

- Allows visual verification of automated gating strategies [1] [8]

Figure 2: Cytometry Method Selection. This decision diagram guides researchers in selecting the appropriate technology based on their specific research needs.

Flow cytometry operates on the fundamental principles of hydrodynamic focusing, laser interrogation, and multiparametric optical detection, enabling high-throughput, quantitative analysis of cellular characteristics at the single-cell level. For cell viability assessment, it provides superior statistical power, multiparametric discrimination of cell death pathways, and enhanced sensitivity compared to fluorescence microscopy, particularly in detecting subtle cellular changes under cytotoxic stress [4].

While fluorescence microscopy maintains advantages in providing spatial context and morphological detail, the strong correlation between both methods (r=0.94) validates fluorescence microscopy as a viable screening tool when flow cytometry is unavailable [4] [5]. However, for detailed mechanistic studies requiring discrimination between apoptotic stages or for high-throughput drug screening applications, flow cytometry, particularly in its advanced spectral and imaging configurations, offers unparalleled capabilities for comprehensive cell viability assessment.

The choice between these technologies should be guided by specific research requirements, with flow cytometry excelling in quantitative, high-throughput applications, and microscopy providing complementary morphological insights. For the most comprehensive viability assessment, an integrated approach leveraging both technologies often yields the most complete understanding of cellular responses to experimental conditions.

The Basic Working Mechanism of Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy is an indispensable imaging technique in biomedical research, enabling scientists to visualize specific molecules and structures within cells and tissues with high contrast and specificity. Unlike conventional light microscopy, which relies on the absorption or refraction of light, fluorescence microscopy detects the light emitted by fluorescent molecules after they have been excited by light of a specific wavelength [9] [10]. This fundamental principle allows researchers to distinguish target components against a dark background, making it a powerful tool for applications ranging from basic cell biology to drug development. Within the context of cell viability assessment, understanding the precise working mechanism of fluorescence microscopy is crucial for comparing its capabilities with alternative technologies like flow cytometry.

Fundamental Principles of Fluorescence

At the core of fluorescence microscopy is the physical phenomenon of fluorescence, which involves the absorption and re-emission of light by a fluorophore.

The Jablonski Diagram and Energy States: A Jablonski energy diagram illustrates the electronic transitions involved in fluorescence. When a fluorophore absorbs a photon of light, one of its electrons is elevated to a higher-energy, excited state. This process occurs in femtoseconds (10â»Â¹âµ seconds). The excited electron first rapidly loses a small amount of energy as heat to its environment (vibrational relaxation), settling into the lowest vibrational level of the excited state. The electron then returns to its ground state, emitting a photon of light in the process. The entire event typically occurs within nanoseconds [11] [12] [13].

Stokes Shift: A critical characteristic of fluorescence is the Stokes Shift, which denotes that the emitted light always has a longer wavelength (lower energy) than the excitation light [11] [10] [14]. This energy loss is due to the vibrational relaxation that occurs in the excited state. The magnitude of the Stokes shift is a key property of a fluorophore; a larger shift makes it easier to separate the strong excitation light from the weaker emitted fluorescence, thereby improving image contrast [10] [13].

Excitation and Emission Spectra: Fluorophores do not absorb and emit light at a single wavelength but across a range of wavelengths. The excitation spectrum is a graph showing the relative efficiency of different wavelengths to excite the fluorophore. The emission spectrum shows the range and relative intensity of wavelengths emitted. These spectra often appear as mirror images but with the emission spectrum shifted to longer wavelengths [14]. The peak of these spectra defines the optimal excitation and emission conditions for a given fluorophore.

Core Components of a Widefield Epifluorescence Microscope

The modern epifluorescence microscope (where "epi" means the same objective lens is used for both excitation and emission) is designed to efficiently deliver excitation light to the sample and then isolate the much weaker emitted fluorescence [15] [16] [10]. Its key components work in a coordinated sequence.

Figure 1: The essential light path and component interaction in a widefield epifluorescence microscope. The filter cube (comprising the excitation filter, dichroic mirror, and emission filter) is critical for separating excitation from emission light.

Detailed Component Functions

High-Intensity Light Source: The process begins with a bright light source that emits a broad spectrum of light. Common sources include mercury or xenon arc-discharge lamps, and increasingly, high-power Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) [15] [17]. Lasers are used in more advanced systems like confocal microscopes.

Excitation Filter: This is an optical filter placed in the light path after the source. It functions as a bandpass filter, allowing only the specific range of wavelengths required to excite the chosen fluorophore to pass through, while blocking other unwanted wavelengths [15] [16] [10].

Dichroic Mirror (Beamsplitter): This is the central, cleverly engineered component of the filter cube. Positioned at a 45-degree angle, the dichroic mirror is an interference filter designed to reflect light below a specific cutoff wavelength and transmit light above it. It reflects the filtered excitation light down through the objective lens onto the specimen [16] [12] [10].

Objective Lens: In epifluorescence microscopy, the objective lens serves a dual purpose. It first acts as a well-corrected condenser, focusing the excitation light onto the sample. Subsequently, it gathers the faint fluorescent light emitted from the specimen [16] [10]. The numerical aperture (NA) of the objective is a key factor determining the resolution and light-gathering ability of the microscope [15].

Emission Filter (Barrier Filter): The fluorescence emission collected by the objective passes back through the dichroic mirror. However, some scattered excitation light may also pass through. The emission filter is a final bandpass filter that blocks any residual excitation light and allows only the desired emission wavelengths to proceed to the detector. This ensures a dark background and a high-contrast fluorescent image [15] [16] [10].

Critical Research Reagents and Staining Methodologies

The utility of fluorescence microscopy hinges on the ability to specifically label target molecules or structures. The table below summarizes key reagents and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Fluorescence Microscopy

| Reagent Type | Key Examples | Primary Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Immunofluorescence Labels | FITC, TRITC, Alexa Fluor dyes (e.g., 488, 568) [15] | Antibody-conjugated organic dyes used for highly specific tagging of proteins in fixed cells and tissues [15] [17]. |

| Fluorescent Proteins | GFP, eGFP, mCherry, BFP [15] | Genetically encoded tags for real-time visualization of protein localization, dynamics, and expression in live cells [15] [17]. |

| Nucleic Acid Stains | DAPI, Hoechst [15] [17] | Small molecules that bind DNA, used for labeling cell nuclei in both live and fixed samples. |

| Organelle-Tracking Dyes | MitoTracker, LysoTracker [18] | Cell-permeant dyes that selectively accumulate in specific organelles, enabling live-cell imaging of structures like mitochondria and lysosomes. |

| Ion Indicators (Chelators) | Fura-2, Indo-1 [18] | Dyes whose fluorescence intensity or spectral properties change with the concentration of specific ions (e.g., Ca²âº), allowing dynamic monitoring of ion fluxes. |

| Antifade Reagents | p-phenylenediamine, DABCO [11] [13] | Compounds added to mounting media to reduce photobleaching (fading), thereby preserving fluorescence signal intensity during prolonged observation. |

Standard Immunofluorescence Protocol

A foundational experimental protocol for visualizing a specific protein in fixed cells involves immunofluorescence [18] [17]:

- Sample Fixation: Cells or tissues are fixed (e.g., with paraformaldehyde) to preserve morphology and immobilize antigens.

- Permeabilization: A detergent (e.g., Triton X-100) is applied to permeabilize cell membranes, allowing antibodies access to intracellular targets.

- Blocking: Incubation with a protein solution (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin) to block non-specific antibody binding sites.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: The sample is incubated with an unlabeled antibody specific to the target protein.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: A fluorophore-conjugated antibody, which recognizes and binds to the primary antibody, is applied. This indirect method amplifies the signal and offers flexibility.

- Mounting and Visualization: The sample is mounted on a slide with an antifade reagent and imaged under the fluorescence microscope using filter sets matched to the fluorophore.

Comparison of Fluorescence Microscopy Modalities

While the basic widefield microscope is powerful, it captures light from the entire specimen, including out-of-focus regions, which can blur the image. Several advanced modalities have been developed to overcome this and other limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Key Fluorescence Microscopy Techniques

| Microscopy Technique | Basic Principle | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Suitability for Cell Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widefield Epifluorescence | Entire field of view is illuminated at once [15]. | Simple, fast, cost-effective; ideal for thin samples and quick screening [15]. | Out-of-focus light reduces contrast and resolution in thick samples [15]. | High throughput but limited to 2D or thin samples; prone to phototoxicity. |

| Laser Scanning Confocal | A laser scans a single point; a pinhole rejects out-of-focus light [15] [12]. | High-resolution optical sectioning; enables 3D reconstruction of thick specimens [15] [9]. | Slower imaging; expensive; high-intensity lasers can cause significant photobleaching and phototoxicity [9]. | Excellent for 3D morphology in fixed cells; phototoxicity a concern for long-term live-cell viability studies. |

| Multiphoton (Two-Photon) | Near-simultaneous absorption of two long-wavelength photons for excitation [12] [9]. | Deeper tissue penetration; reduced phototoxicity and out-of-focus bleaching outside the focal plane [12] [9]. | Very expensive due to requirement for pulsed infrared lasers [9]. | Superior for long-term imaging of cell viability in thick tissues (e.g., live brain slices, spheroids). |

| Total Internal Reflection (TIRF) | Uses an evanescent field to excite fluorophores only within ~100 nm of the coverslip [9]. | Extremely high signal-to-noise ratio for imaging processes at the cell membrane [9]. | Limited to surface-associated events. | Ideal for studying exocytosis/endocytosis, adhesion dynamics in live cells with minimal background. |

Limitations and Considerations for Cell Viability Research

When applying fluorescence microscopy for cell viability assessment, several technical constraints must be considered:

- Photobleaching: The irreversible destruction of fluorophores under prolonged or intense illumination, leading to signal loss [11] [17]. This can be mitigated with antifade reagents and by minimizing light exposure [11] [13].

- Phototoxicity: The generation of reactive chemical species during fluorescence excitation can damage cellular components and compromise viability, a critical concern in live-cell imaging [17]. Using longer-wavelength light (e.g., in multiphoton microscopy), lower light intensities, and more sensitive detectors can reduce this effect [12].

- Indirect Measurement: Fluorescence microscopy typically reveals the location of a labeled component but not the viability state directly. Viability is inferred using dyes that indicate membrane integrity (e.g., propidium iodide) or enzymatic activity, which may require careful interpretation and control experiments.

The basic working mechanism of fluorescence microscopy—founded on the principles of Stokes shift and the precise optical separation of excitation and emission light—makes it an exceptionally powerful tool for spatial and functional analysis in biological research. Its versatility, driven by a vast toolkit of fluorescent reagents and specialized modalities, allows researchers to visualize everything from single molecules to dynamic processes in living organisms. In the specific context of cell viability assessment, while techniques like widefield microscopy offer high-speed screening, confocal and multiphoton microscopy provide the 3D resolution and reduced phototoxicity necessary for rigorous, long-term investigation of living systems. A deep understanding of this mechanism and its associated technologies is fundamental for designing robust experiments and for making an informed comparison with high-throughput but lower-resolution techniques like flow cytometry.

In the field of cell biology and biomaterial research, the choice of analytical technique profoundly influences the type and quality of data obtained. Two dominant paradigms have emerged: high-throughput analysis, characterized by its ability to rapidly quantify large cell populations, and spatial localization, which preserves and analyzes the architectural context of cells within their native environment. Flow cytometry epitomizes the high-throughput approach, enabling rapid, single-cell quantification of multiple parameters across thousands of cells per second. In contrast, fluorescence microscopy provides detailed spatial context, allowing researchers to visualize subcellular structures, cell-to-cell interactions, and morphological features within intact samples. This guide objectively compares these methodologies within the specific context of cell viability assessment, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodological insights needed to select the appropriate tool for their research objectives.

The fundamental distinction lies in what each technique optimizes for: flow cytometry excels in statistical power and multiparametric quantification of cell populations in suspension, while fluorescence microscopy preserves spatial relationships and morphological detail in situ. This trade-off between throughput and contextual information frames the comparative landscape, influencing applications from basic research to preclinical drug development and biomaterial safety testing [19] [4].

Technical Comparison: Capabilities and Limitations

Table 1: Core Technical Characteristics of Flow Cytometry and Fluorescence Microscopy

| Feature | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (thousands of cells/second) | Low to Moderate (limited by field of view) |

| Spatial Context | Lost (cells in suspension) | Preserved (cells in situ) |

| Primary Output | Quantitative population data | Qualitative images & morphometric data |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (10+ parameters simultaneously) | Moderate (limited by spectral overlap) |

| Key Strength | Statistical significance, subpopulation discrimination | Cellular morphology, localization, integrity |

| Primary Limitation | No spatial information, requires single-cell suspension | Lower throughput, potential observer bias |

| Automation Potential | High | Moderate (especially with automated stages) |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in a Direct Comparative Viability Study [19] [4]

| Experimental Condition | Viability via Fluorescence Microscopy (FDA/PI) | Viability via Flow Cytometry (Multiparametric Staining) |

|---|---|---|

| Control Cells | >97% | >97% |

| <38 µm BG, 100 mg/mL, 3h | 9% | 0.2% |

| <38 µm BG, 100 mg/mL, 72h | 10% | 0.7% |

| Data Correlation | Strong correlation (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001) | |

| Additional Data | Live/Dead distinction only | Distinction of viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations |

The data from a direct comparative study on bioactive glass (BG) cytotoxicity reveals a strong correlation between the two techniques, validating both for viability assessment. However, flow cytometry demonstrated superior sensitivity and precision, particularly under high cytotoxic stress, detecting drastically lower viability percentages than fluorescence microscopy. This is attributed to its ability to analyze every cell in a sample and its more precise discrimination of dim fluorescence signals. Furthermore, flow cytometry's multiparametric capacity provided a deeper mechanistic insight by distinguishing between early and late apoptosis and necrosis, whereas microscopy primarily offered a binary live/dead classification [19] [4].

Beyond standard flow cytometry, spectral flow cytometry represents a significant advancement. Unlike conventional flow cytometry, which measures peak emissions with limited detectors, spectral cytometry uses multiple detectors to capture the full emission spectrum for each fluorochrome. This allows for superior unmixing of dyes with highly overlapping spectra, enabling the use of more parameters in a single panel and improving resolution by characterizing and subtracting cellular autofluorescence [20].

Similarly, fluorescence microscopy is evolving. New techniques like Super-resolution Panoramic Integration (SPI) microscopy overcome traditional diffraction limits, enabling instant generation of sub-diffraction images with a twofold resolution enhancement (~120 nm) while maintaining high-throughput capabilities, imaging thousands of cells per second. This bridges the gap between the high resolution of traditional microscopy and the need for population-level analysis [21].

Experimental Protocols for Cell Viability Assessment

Flow Cytometry Protocol for Multiparametric Viability and Death Mechanism Analysis

This protocol leverages the high-throughput, multi-parameter capabilities of flow cytometry to not only determine viability but also to distinguish the mechanism of cell death, which is crucial for understanding material cytotoxicity or drug mechanisms [19].

- 1. Cell Preparation and Staining: Harvest and wash cells. Resuspend the cell pellet in a suitable buffer. For a comprehensive view, stain with a cocktail of fluorescent probes. A typical panel includes:

- Hoechst 33342: A cell-permeant DNA stain that labels all nucleated cells, allowing for the identification of the entire cell population.

- Annexin V-FITC: Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS), which is externalized to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during early apoptosis.

- Propidium Iodide (PI) or other cell-impermeant DNA stain: Enters cells with compromised plasma membranes, marking late apoptotic and necrotic cells.

- 2. Incubation and Analysis: Incubate the stained cells according to the specific requirements of each dye (typically 15-20 minutes at room temperature, protected from light). Analyze the cells immediately on a flow cytometer. A minimum of 10,000 events per sample is recommended for robust statistics.

- 3. Data Gating and Interpretation:

- Gate on the Hoechst-positive population to exclude debris.

- Create a dot plot of Annexin V-FITC vs. PI.

- Viable cells are Annexin V-negative/PI-negative.

- Early apoptotic cells are Annexin V-positive/PI-negative.

- Late apoptotic cells are Annexin V-positive/PI-positive.

- Necrotic cells are Annexin V-negative/PI-positive (though this can vary depending on the timing of membrane rupture).

Fluorescence Microscopy Protocol for Live/Dead Viability Staining

This protocol is ideal for visualizing cell death in situ, allowing for the observation of morphological changes and spatial patterns of cytotoxicity [19] [22].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Culture cells directly on glass-bottom dishes or coverslips, especially when testing biomaterials or surface treatments.

- 2. Staining: Prepare a working solution of viability stains in culture medium or buffer. A common combination is:

- Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA): A cell-permeant, non-fluorescent compound that is converted by intracellular esterases into fluorescent fluorescein, retained only in live cells.

- Propidium Iodide (PI): As above, it labels the nuclei of dead cells.

- 3. Incubation and Imaging: Replace the culture medium with the staining solution and incubate for a short period (e.g., 5-15 minutes at 37°C). Image the cells immediately using a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets for FITC (green, for FDA) and TRITC/Texas Red (red, for PI).

- 4. Image Analysis: Acquire multiple, random fields of view to minimize sampling bias. Count or use image analysis software to quantify the number of green (live) and red (dead) cells. Viability is calculated as the percentage of live cells from the total counted cells.

Diagram 1: Flow cytometry multiparametric viability analysis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Cell Viability Assessment [22]

| Reagent Name | Function / Mechanism | Compatible Platform(s) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | DNA-binding dead cell stain; membrane integrity. | FC, FM | Cell-impermeant; red fluorescence upon DNA binding. |

| 7-AAD | DNA-binding dead cell stain; membrane integrity. | FC, FM | Cell-impermeant; used in cell cycle and chromosome studies. |

| SYTOX Green/Blue/Orange | DNA-binding dead cell stain; membrane integrity. | FC, FM, M | Non-fluorescent in solution; bright upon DNA binding; no wash step. |

| Annexin V (FITC, etc.) | Binds phosphatidylserine exposed on apoptotic cells. | FC, FM | Marker for early apoptosis; requires calcium buffer. |

| Hoechst 33342 | Cell-permeant DNA stain; labels all nucleated cells. | FC, FM | Labels all cells; used for population gating and total cell count. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Converted to fluorescent fluorescein by live cell esterases. | FM | Metabolic activity marker for live cells. |

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Viability Stains | Amine-reactive dye; dim in live cells, bright in dead cells. | FC | Fixable; allows sample fixation post-staining. |

| Image-iT DEAD Green | Membrane integrity dead cell stain. | FC, FM | Green-fluorescent; fixable. |

| FDGal | FDGal | 2-[18F]FDGal for quantitative liver function PET/CT studies. For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. | Bench Chemicals |

| Erbon | Erbon, CAS:136-25-4, MF:C11H9Cl5O3, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

FC = Flow Cytometry, FM = Fluorescence Microscopy, M = Microplate Assay

Diagram 2: Technique selection workflow for viability analysis.

The comparative analysis between high-throughput flow cytometry and spatial localization via fluorescence microscopy reveals that the choice is not a matter of which technique is universally superior, but which is more appropriate for the specific research question. Flow cytometry provides unmatched statistical power, sensitivity, and detailed mechanistic classification of cell death, making it ideal for screening applications and quantifying subtle population changes. Fluorescence microscopy, meanwhile, offers indispensable spatial context and morphological detail, crucial for understanding cell-material interactions, tissue architecture, and localized effects.

The future of cellular analysis lies in the convergence of these paradigms. Technologies like imaging flow cytometry combine the high-throughput, multiparametric strength of flow cytometry with the morphological information of microscopy, allowing for the identification of distinct spatial configurations of proteins like CAR in T cells directly from a heterogeneous sample [23]. Similarly, advancements in spatial proteomics and transcriptomics are pushing microscopy toward more multiplexed, high-content analysis, enabling the mapping of dozens to hundreds of biomarkers within their native tissue architecture [24] [25]. For the most comprehensive understanding, many sophisticated research workflows now integrate both techniques, using microscopy for initial spatial observation and flow cytometry for deep, quantitative validation.

Flow Cytometry (FCM) and Fluorescence Microscopy (FM) are foundational techniques in cell viability assessment, yet they generate fundamentally different types of data. FCM provides high-throughput, multi-parametric statistical data for thousands of cells, offering robust quantitative analysis. In contrast, FM produces high-resolution visual images that preserve the spatial context and morphology of cells. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each method is crucial for researchers in biomaterial science and drug development. This guide objectively compares their performance using recent experimental data.

Quantitative Data Comparison

A direct comparative study investigating the cytotoxicity of Bioglass 45S5 (BG) on SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells provides clear performance metrics for both techniques [19] [4]. The following tables summarize the key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Cell Viability Outcomes Measured by FCM and FM

| Particle Size | Concentration (mg/mL) | Time (h) | Viability by FM (%) | Viability by FCM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 38 µm | 100 | 3 | 9 | 0.2 |

| < 38 µm | 100 | 72 | 10 | 0.7 |

| Controls (Various) | N/A | 3 & 72 | > 97 | > 97 |

Table 2: Correlation of Techniques and Key Differentiating Features

| Parameter | Findings |

|---|---|

| Statistical Correlation | Strong correlation between FM and FCM data (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001) [19]. |

| Cell Death Differentiation | FM: Distinguishes viable and non-viable cells [19].FCM: Classifies viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations [19] [4]. |

| Precision | FCM demonstrated superior precision, particularly under high cytotoxic stress [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The data presented in the tables above were generated under controlled and identical experimental conditions to ensure a fair comparison [19] [4].

Cell Culture and Treatment

- Cell Line: Human SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells were used due to their robust osteogenic phenotype [19].

- Test Material: Bioglass 45S5 (BG) particles were used to induce a gradient of cytotoxic stress.

- Experimental Conditions: Cells were exposed to BG particles of three size ranges (< 38 µm, 63–125 µm, and 315–500 µm) at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL for 3 and 72 hours [19].

Fluorescence Microscopy (FM) Protocol

- Staining: Cells were stained with Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) and Propidium Iodide (PI). FDA is metabolized by live cells to produce green fluorescence, while PI enters dead cells with compromised membranes and intercalates into DNA, producing red fluorescence [19] [4].

- Imaging & Analysis: Stained cells were visualized using a conventional widefield fluorescence microscope. Viability was determined by manually or digitally counting cells exhibiting green (viable) versus red (non-viable) fluorescence [19]. This process is labor-intensive and can be subject to sampling bias, as only a few fields of view are analyzed [19].

Flow Cytometry (FCM) Protocol

- Staining: A multiparametric staining panel was employed, including:

- Hoechst: Stains DNA for general cell identification and gating.

- DiIC1: A lipophilic cationic dye that accumulates in the mitochondria of live cells.

- Annexin V-FITC: Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the outer leaflet of the cell membrane during early apoptosis.

- Propidium Iodide (PI): As above, indicating late apoptosis or necrosis when the cell membrane is compromised [19] [4].

- Analysis: The single-cell suspension was hydrodynamically focused and passed through a laser beam. The scattered and fluorescent light signals from each cell were detected and quantified [19] [26]. This allows for the automated, high-throughput classification of thousands of cells per second into distinct viability states based on their staining profile [19].

Workflow and Technique Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core functions of each technique and the type of data they generate, highlighting their complementary nature.

Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of these protocols relies on specific reagents and materials. The table below details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cell Viability Assays

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | A red-fluorescent DNA intercalator that is excluded by viable cells. Used to label dead cells [19] [4]. | A standard component in live/dead staining kits for both FCM and FM [19]. |

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | A cell-permeant esterase substrate. Metabolized in live cells to produce green fluorescence [4]. | Used in FM for visual identification of viable cells [19] [4]. |

| Annexin V-FITC | Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS) exposed on the cell surface during early apoptosis. Requires co-staining with PI for viability context [19]. | Enables FCM to distinguish early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-) from late apoptotic/necrotic (Annexin V+/PI+) cells [19]. |

| Hoechst Stains | Cell-permeant blue-fluorescent nucleic acid stains. Used for general cell counting and gating in FCM [19]. | Helps identify and select the entire cell population in complex FCM plots [19]. |

| Antifade Mounting Media | Reagents that minimize photobleaching of fluorophores during microscopy by inhibiting reactive oxygen species [27]. | Critical for preserving fluorescence signal in FM samples (e.g., ProLong Gold, SlowFade Gold) [27]. |

Protocols in Practice: Staining, Assays, and Real-World Applications

In the field of biomaterial research and preclinical cytotoxicity assessment, accurately determining cell viability is a fundamental requirement. Among the various techniques available, fluorescence microscopy (FM) and flow cytometry (FCM) have emerged as two prominent methods, each employing distinct staining methodologies to differentiate between live and dead cells [19]. The selection of an appropriate staining panel directly influences the accuracy, depth, and reliability of the viability data obtained. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison between two standard staining approaches: the FDA/PI (Fluorescein Diacetate/Propidium Iodide) panel conventionally used with Fluorescence Microscopy, and the multiparametric staining panels (e.g., Hoechst, DiIC1, Annexin V-FITC, PI) designed for Flow Cytometry. Understanding the principles, applications, and performance characteristics of these staining panels is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to optimize their experimental designs and correctly interpret cellular responses to cytotoxic stimuli, such as those induced by particulate biomaterials [19] [4].

Staining Panel Specifications and Mechanisms

The core difference between these staining panels lies in their complexity and the breadth of information they deliver. The FDA/PI panel offers a fundamental live/dead distinction, whereas the multiparametric FCM panel enables a detailed dissection of cell death pathways.

FDA/PI Staining for Fluorescence Microscopy

The FDA/PI staining panel is a widely adopted two-color assay for direct visualization of cell viability.

- Viable Cells (FDA): Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) is a non-fluorescent, cell-permeant compound. Once inside a viable cell, intracellular esterases cleave the acetate groups, converting it to fluorescein, a green-fluorescent compound (typically excited at ~488 nm and emitting at ~530 nm) that is retained in cells with intact plasma membranes [4].

- Non-Viable Cells (PI): Propidium iodide (PI) is a red-fluorescent nucleic acid stain (excitation maximum ~535 nm, emission maximum ~617 nm) that is impermeant to live cells. It only enters cells with compromised plasma membranes, binding to DNA and RNA [28].

This mechanism allows for a straightforward binary classification where green fluorescence indicates viability and red fluorescence indicates cell death, visualized directly via the fluorescence microscope.

Multiparametric Staining for Flow Cytometry

Advanced flow cytometry utilizes panels with multiple fluorescent markers to provide a nuanced view of cell status. A representative panel, as used in a recent comparative study, includes Hoechst, DiIC1, Annexin V-FITC, and PI [19] [4].

- Viable Cells (Hoechst & DiIC1): Hoechst stains DNA in all cells and is often used for gating. DiIC1 is a carbocyanine dye that accumulates in the mitochondria of cells with active membrane potentials, serving as an indicator of metabolic activity and early viability [19].

- Early Apoptotic Cells (Annexin V-FITC): Annexin V is a protein that binds to phosphatidylserine (PS). In viable cells, PS is located on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane. During early apoptosis, PS is translocated to the outer leaflet, where it can be stained by Annexin V conjugated to FITC (green fluorescence), while the membrane remains intact, excluding PI [4].

- Late Apoptotic/Necrotic Cells (Annexin V-FITC & PI): In late apoptosis and necrosis, the cell membrane becomes permeable, allowing PI (red fluorescence) to enter and stain the nucleic acids. Cells that stain positive for both Annexin V and PI are typically classified as late apoptotic or necrotic [19] [4].

This multi-parameter approach enables the classification of cells into viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations.

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for both staining methods, from sample preparation to final analysis.

Comparative Experimental Data

A direct comparative study exposed SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells to Bioglass 45S5 (BG) particles of varying sizes and concentrations, applying both staining panels under identical conditions to benchmark their performance [19] [29]. The results are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Viability Assessment under Cytotoxic Stress

Cell viability (%) of SAOS-2 cells exposed to <38 µm BG particles at 100 mg/mL [19] [4].

| Assessment Technique | Staining Panel | Viability at 3 Hours | Viability at 72 Hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Microscopy (FM) | FDA / PI | 9% | 10% |

| Flow Cytometry (FCM) | Hoechst / DiIC1 / Annexin V-FITC / PI | 0.2% | 0.7% |

Key Findings:

- Strong Correlation, Different Sensitivity: Despite the stark difference in absolute values, the data from both techniques showed a strong statistical correlation (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001) across all tested conditions [19] [4]. This confirms that both can reliably track cytotoxic trends.

- Superior FCM Sensitivity: The multiparametric FCM panel consistently reported lower viability percentages under high cytotoxic stress, suggesting a higher sensitivity and resolution for detecting compromised cells that might still be scored as viable by the FM-based method [19].

- Mechanistic Insight: A key advantage of the FCM panel was its ability to differentiate the mode of cell death. It distinguished early apoptotic populations (Annexin V-FITC positive, PI negative) from late apoptotic/necrotic populations (Annexin V-FITC positive, PI positive), providing a deeper understanding of the biomaterial's cytotoxic mechanism [19] [4].

Detailed Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility, the experimental protocols for both staining methods are detailed below.

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Seed SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells in culture plates and allow them to adhere. Treat with the test particulate biomaterial (e.g., Bioglass 45S5) at desired concentrations and durations.

- Staining Solution Preparation: Prepare a working solution containing Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) and Propidium Iodide (PI) in a suitable buffer, such as phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Staining Incubation: After the treatment period, remove the culture medium and gently wash the cells with PBS. Add the FDA/PI working solution to cover the cells and incubate for a specified time (e.g., 5-15 minutes) at room temperature, protected from light.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Remove the staining solution, replace with fresh buffer, and immediately visualize using a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets for FITC (green) and TRITC/Texas Red (red). Capture multiple random fields. Viability is quantified as the percentage of green-fluorescent cells relative to the total number of cells (green + red).

- Cell Harvesting: After treatment, harvest the cells from the culture substrate, typically using trypsinization followed by centrifugation to form a cell pellet.

- Staining for Viability and Apoptosis: Resuspend the cell pellet in a binding buffer.

- Add Annexin V-FITC and incubate for 10-15 minutes in the dark.

- Add Propidium Iodide (PI) and other dyes like Hoechst (for DNA content/nuclear staining) or DiIC1 (for mitochondrial membrane potential) shortly before analysis, as per manufacturer's instructions.

- Flow Cytometric Analysis: Analyze the stained cell suspension on a flow cytometer equipped with lasers and filters appropriate for the fluorochromes used (e.g., 488 nm for FITC and PI, 405 nm for Hoechst, 638 nm for DiIC1). Collect a sufficiently high number of events (e.g., 10,000 cells).

- Data Analysis and Gating: Use sequential gating to identify the cell population of interest (e.g., based on forward/side scatter and Hoechst staining). Then, create a biparametric plot of Annexin V-FITC vs. PI to distinguish the subpopulations:

- Annexin V-FITCâ» / PIâ»: Viable cells.

- Annexin V-FITC⺠/ PIâ»: Early apoptotic cells.

- Annexin V-FITC⺠/ PIâº: Late apoptotic or necrotic cells.

The logical relationship of how these stains work together to classify cell states in the FCM panel is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental to the success of these viability assays. The following table details the key components used in the featured staining panels.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Cell Viability Assessment

| Reagent / Dye | Function / Mechanism | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA) | Cell-permeant substrate for intracellular esterases; produces green fluorescein in viable cells. | FM Live/Dead Staining |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Cell-impermeant DNA intercalator; red fluorescence indicates loss of membrane integrity. | FM & FCM (Necrosis/Late Apoptosis) |

| Annexin V-FITC | Binds phosphatidylserine (PS) on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane; indicates early apoptosis. | FCM Apoptosis Detection |

| Hoechst Stains | Cell-permeant DNA stain; labels all nuclei, used for cell gating and enumeration. | FCM Nuclear Staining |

| DiIC1(5) | Carbocyanine dye that accumulates in active mitochondria; indicates mitochondrial membrane potential. | FCM Viability / Metabolism |

| Fixable Viability Dyes | Amine-reactive dyes that covalently bind to non-viable cells; allow subsequent cell fixation. | FCM (excluded from viable cells) [30] |

| Borax (B4Na2O7.10H2O) | Borax (Sodium Tetraborate) | |

| (3,5-Dibromophenyl)(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)methanone | (3,5-Dibromophenyl)(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)methanone, CAS:1310355-45-3, MF:C14H7Br2F3O, MW:408.012 | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between the standard FDA/PI panel for FM and multiparametric panels for FCM hinges on the specific research requirements regarding information depth, sensitivity, and throughput.

- FDA/PI for Fluorescence Microscopy provides a straightforward, cost-effective, and visually intuitive method for basic viability assessment. It is an excellent tool for initial screening and for experiments where direct morphological observation is beneficial.

- Multiparametric Panels for Flow Cytometry offer a superior, high-resolution analysis of cell health. Their principal advantage lies in the ability to distinguish between viable, early apoptotic, and late apoptotic/necrotic cell populations, providing mechanistically rich data [19] [4]. FCM demonstrates higher sensitivity, especially under conditions of severe cytotoxic stress, and enables the high-throughput analysis of thousands of cells, minimizing sampling bias [19].

For studies where understanding the pathway of cell death is critical, or where the highest level of quantitative precision is required, multiparametric flow cytometry is the unequivocally more powerful technique. However, for rapid, accessible live/dead assessment, FDA/PI staining combined with fluorescence microscopy remains a valid and widely used approach, particularly when its limitations regarding sensitivity and mechanistic insight are acknowledged.

Reliable assessment of biomaterial cytotoxicity is a cornerstone of preclinical evaluation in biomedical research and drug development. Among the various methods available, fluorescence microscopy (FM) and flow cytometry (FCM) stand out as widely used techniques for determining cell viability. However, their comparative performance in the context of particulate systems, such as bioactive glasses, has remained underexplored. This guide provides a direct, data-driven comparison of these two methodologies, focusing on their application in evaluating the cytotoxicity of Bioglass 45S5 (BG) on SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells. The findings are critical for researchers aiming to select the most appropriate, sensitive, and reliable technique for their biomaterial compatibility testing.

Experimental Setup & Quantitative Comparison

This analysis is based on a 2025 comparative study that exposed SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells to BG particles of different sizes and concentrations, assessing viability at two time points using both FM and FCM under identical conditions [19] [29].

- Test Material: Bioglass 45S5 (BG) particles in three size ranges: <38 µm, 63–125 µm, and 315–500 µm [19].

- Cell Line: SAOS-2 human osteosarcoma cell line, chosen for its mature osteoblast-like phenotype [19].

- Experimental Conditions: Cells were treated with BG at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 mg/mL for 3 and 72 hours [19].

- Viability Staining:

- Fluorescence Microscopy (FM): Used FDA (fluorescein diacetate) and PI (propidium iodide) to distinguish viable (green) from non-viable (red) cells [19] [4].

- Flow Cytometry (FCM): Employed a multiparametric stain (Hoechst, DiIC1, Annexin V-FITC, and PI) to classify cells into viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations [19] [4].

Both techniques confirmed that smaller particles and higher concentrations caused greater cytotoxicity [19]. The most pronounced effect was observed for the smallest particles (<38 µm) at the highest concentration (100 mg/mL). The table below summarizes the viability measurements under these conditions, highlighting the critical difference between the two methods.

Table 1: Cell Viability Under High Cytotoxic Stress (<38 µm BG at 100 mg/mL)

| Time Point | Fluorescence Microscopy (FM) Viability | Flow Cytometry (FCM) Viability |

|---|---|---|

| 3 hours | 9% | 0.2% |

| 72 hours | 10% | 0.7% |

| Control Viability | >97% | >97% |

Despite the significant difference in absolute values, a strong statistical correlation was found between the datasets from both techniques (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001) [19] [4]. This validates FM as a useful screening tool but also underscores FCM's superior sensitivity, especially under high cytotoxic stress.

Detailed Methodologies

Fluorescence Microscopy (FM) Protocol

The FM protocol offers direct visual assessment of cell cultures. The following diagram outlines the core workflow for this method.

Step-by-Step Procedure [19]:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells are seeded in culture plates and exposed to the prepared BG particles at the desired concentrations.

- Incubation: Cells are incubated with the particles for the designated time (e.g., 3 or 72 hours).

- Staining: The culture medium is replaced with a solution containing the fluorescent stains.

- FDA (Fluorescein diacetate): A cell-permeant esterase substrate. Metabolically active viable cells convert it into fluorescent fluorescein (green emission).

- PI (Propidium iodide): A cell-impermeant DNA stain. It only enters cells with compromised plasma membranes (dead cells) and emits red fluorescence.

- Washing and Visualization: Unbound stain is washed off, and the cells are immediately visualized under a fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets.

- Image Analysis: Multiple random fields of view are captured. Viable (green) and non-viable (red) cells are counted manually or using image analysis software to calculate the percentage viability.

Flow Cytometry (FCM) Protocol

The FCM protocol provides a high-throughput, quantitative analysis of individual cells in suspension. The workflow is more complex, involving several staining steps to differentiate cell states.

Step-by-Step Procedure [19]:

- Cell Seeding and Treatment: Identical to the FM protocol.

- Incubation: Identical to the FM protocol.

- Cell Harvesting: After incubation, cells are detached from the culture surface using trypsin-EDTA to create a single-cell suspension—a critical step for FCM.

- Multiparametric Staining: The cell suspension is stained with a panel of dyes:

- Hoechst: A cell-permeant blue fluorescent DNA stain, often used to identify nucleated cells.

- DiIC1(5): A lipophilic cyanine dye that accumulates in the mitochondria of viable cells, reflecting mitochondrial membrane potential.

- Annexin V-FITC: Binds to phosphatidylserine (PS), which is externalized to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during early apoptosis (green fluorescence).

- PI: As in FM, it labels cells with permeable membranes (late apoptotic and necrotic cells).

- Data Acquisition: The stained cell suspension is run through a flow cytometer. The instrument analyzes thousands of cells per second, measuring light scattering and fluorescence parameters for each cell.

- Gating and Analysis: Data analysis software is used to identify cell populations based on their staining profiles:

- Viable cells: Annexin V-/PI-

- Early apoptotic cells: Annexin V+/PI-

- Late apoptotic cells: Annexin V+/PI+

- Necrotic cells: Annexin V-/PI+

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in Cell Viability Assays

| Reagent | Function | Assay Type |

|---|---|---|

| FDA (Fluorescein Diacetate) | Metabolized by esterases in viable cells to produce green fluorescence. | Fluorescence Microscopy |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) | Binds to DNA in cells with compromised membranes; red fluorescent. | FM & Flow Cytometry |

| Annexin V-FITC | Binds to phosphatidylserine exposed on the surface of apoptotic cells. | Flow Cytometry |

| Hoechst Stains | Cell-permeant blue fluorescent DNA stains; identifies nucleated cells. | Flow Cytometry |

| DiIC1(5) | Dye that accumulates in active mitochondria based on membrane potential. | Flow Cytometry |

| CellTrace Violet | Fluorescent cell staining dye for tracking cell division and proliferation. | Flow Cytometry [31] |

| BrdU (Bromodeoxyuridine) | Thymidine analog incorporated into DNA during synthesis; marks S-phase cells. | Flow Cytometry [31] |

| JC-1 | Dye used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). | Flow Cytometry [31] |

| Sag1.3 | Sag1.3, CAS:912545-86-9, MF:C28H28ClN3OS, MW:490.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IT1t | IT1t, MF:C21H34N4S2, MW:406.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion & Recommendations for Researchers

This comparative case study reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each technique, guiding researchers in their selection.

- Resolution and Sensitivity: Flow cytometry demonstrated superior sensitivity, detecting drastically lower viability levels (0.2-0.7%) under high-stress conditions compared to microscopy (9-10%) [19]. This is likely because FCM can analyze a much larger number of cells (tens of thousands), minimizing sampling bias, whereas FM only assesses a few hundred cells in selected fields of view [19].

- Cellular Insight: A key advantage of FCM is its multiparametric capability. While FM provides a simple live/dead classification, FCM differentiates between early and late apoptosis and necrosis [19] [4]. This offers deeper mechanistic insights into the cell death pathways triggered by the biomaterial.

- Practical Considerations: FM allows direct visualization of cell-particle interactions and morphology, which can be valuable. However, it is more labor-intensive for quantification and susceptible to operator bias [19]. While FCM requires specialized instrumentation and a more complex sample preparation (including creating a single-cell suspension), it provides high-throughput, objective, and quantitative data [19].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice depends on the study's goals:

- Use fluorescence microscopy for initial screening, when direct visualization is crucial, or when access to flow cytometry is limited.

- Choose flow cytometry for high-throughput, quantitative studies requiring high statistical power, sensitivity under high cytotoxicity, and detailed information on the mode of cell death (apoptosis vs. necrosis).

The strong correlation between the methods means they can be used complementarily, but the evidence strongly supports FCM as the more robust and informative tool for the precise cytocompatibility evaluation of particulate biomaterials [19] [4].

Flow Cytometry vs. Fluorescence Microscopy for Cell Viability Assessment

Cell viability assessment is a cornerstone of biomedical research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development, providing crucial insights into cellular health and function under various experimental conditions. Among the numerous techniques available, flow cytometry (FCM) and fluorescence microscopy (FM) have emerged as two prominent methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Flow cytometry is a laser-based technology that enables rapid multi-parametric analysis of single cells in solution, generating both scattered and fluorescent light signals that provide information about cell size, granularity, and biomarker expression [32]. In contrast, fluorescence microscopy utilizes specific fluorescent dyes or proteins to visualize cellular structures and processes, allowing for direct imaging of cells and tissues [33]. The selection between these techniques significantly impacts the quality, depth, and interpretation of experimental data in various research contexts.

This comprehensive guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy across three critical application areas: immunophenotyping, apoptosis detection, and clinical diagnostics. By examining experimental data, technical capabilities, and practical considerations, we aim to provide researchers with evidence-based insights to inform their methodological selections. Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of each approach is essential for optimizing experimental design, ensuring data reliability, and advancing scientific discovery in cell biology and related fields.

Technical Principles and Instrumentation

Flow Cytometry Fundamentals

Flow cytometry operates on the principle of hydrodynamic focusing, where cells in suspension are aligned in a single-file stream through a laser interrogation point. As cells pass through the laser beam, they scatter light and may emit fluorescence from labeled antibodies or dyes. The instrumentation consists of three main systems: fluidics, optics, and electronics [32]. The fluidics system delivers and focuses the sample to the laser intercept point; the optical system includes excitation sources (lasers) and collection optics (filters and detectors); while the electronic system converts the detected signals into digital data [32].

Key measurements in flow cytometry include forward scatter (FSC), which correlates with cell size, and side scatter (SSC), which indicates cellular granularity or internal complexity [32] [34]. Fluorescence detection enables multiparametric analysis, with modern instruments capable of simultaneously measuring up to 30-50 parameters using multiple laser systems and sophisticated detector arrays [34]. Advanced flow cytometer variants include cell sorters (e.g., FACS), which can physically separate cell populations based on defined characteristics; imaging flow cytometers that combine microscopy with traditional FCM; mass cytometers that use heavy metal tags instead of fluorochromes; and spectral analyzers that measure entire emission spectra to improve multiparametric resolution [32].

Fluorescence Microscopy Fundamentals

Fluorescence microscopy operates on the principle of exciting fluorophores with specific wavelengths of light and detecting the emitted light at longer wavelengths. Conventional widefield fluorescence microscopy illuminates the entire sample and captures emitted light through an objective lens, enabling visualization of specific molecules or structures within cells and tissues [33]. The technique relies on fluorescent reagents such as fluorescently conjugated antibodies, DNA binding dyes, viability dyes, and fluorescent proteins to label cellular components [33].

The resolution of traditional fluorescence microscopy is limited by the diffraction barrier (approximately 200 nm), though super-resolution techniques have been developed to overcome this limitation [33]. Fluorescence microscopy allows direct observation of cellular localization, morphology, and dynamic processes through time-lapse imaging. However, it faces challenges including shallow depth of field, photobleaching, phototoxicity, autofluorescence interference, and difficulties in accurately distinguishing between live and dead cells when used for viability assessment [33]. Manual counting or image analysis can be labor-intensive, potentially undermining precision and throughput compared to automated methods [33].

Comparison of fundamental workflows for flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy techniques.

Comparative Performance in Key Applications

Immunophenotyping Capabilities

Immunophenotyping represents one of the most common applications of flow cytometry, enabling the characterization and quantification of heterogeneous cell populations based on surface and intracellular marker expression. The technology excels in this domain due to its ability to simultaneously analyze multiple parameters on individual cells within mixed populations [34]. Modern flow cytometers can detect up to 30 colors in a single experiment, with routine panels typically comprising 15-20 markers for comprehensive immunophenotyping [34]. This multiparametric capacity allows researchers to identify rare cell populations, characterize complex immune subsets, and assess cellular activation states with statistical robustness derived from high cell throughput.

Fluorescence microscopy offers complementary advantages for immunophenotyping, particularly in providing spatial context and morphological detail. Through techniques such as immunofluorescence staining and multilabel imaging, researchers can visualize protein localization, cell-cell interactions, and tissue architecture [33]. However, conventional fluorescence microscopy has limitations in the number of parameters that can be simultaneously assessed due to spectral overlap, and throughput is significantly lower compared to flow cytometry [33]. While advanced imaging platforms and spectral unmixing approaches have expanded these capabilities, flow cytometry remains superior for high-dimensional immunophenotyping of dissociated cells, whereas microscopy provides essential spatial information in intact samples.

Table 1: Immunophenotyping Comparison

| Parameter | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (up to 30-50 parameters simultaneously) [34] | Moderate (typically 4-7 labels due to spectral overlap) [33] |

| Throughput | Very high (10,000+ cells/second) [2] | Low to moderate (limited by imaging and analysis speed) [33] |

| Spatial Context | Limited (cells in suspension) | Excellent (preserved tissue architecture and subcellular localization) [33] |

| Data Output | Quantitative population statistics | Qualitative visualization with semi-quantitative analysis [33] |

| Rare Population Detection | Excellent (statistical power from high cell numbers) | Challenging (limited field of view and sampling bias) [33] |

Apoptosis Detection Sensitivity

The comparative performance of flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy in apoptosis detection was rigorously evaluated in a 2025 study investigating bioactive glass cytotoxicity on SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells [33] [29]. Both techniques confirmed a clear trend of increased cytotoxicity with smaller particle sizes and higher concentrations, but revealed important differences in sensitivity and resolution of apoptotic stages. Fluorescence microscopy employing FDA/PI staining could distinguish viable from nonviable cells but offered limited capacity to differentiate stages of cell death [33]. In contrast, flow cytometry utilizing multiparametric staining (Hoechst, DiIC1, Annexin V-FITC, and PI) enabled precise classification of viable, early apoptotic, late apoptotic, and necrotic populations [33] [29].

Under high cytotoxic stress conditions (particles <38 μm at 100 mg/mL), fluorescence microscopy reported viability of 9% at 3 hours and 10% at 72 hours, while flow cytometry detected more extreme viability reductions to 0.2% and 0.7% respectively [33] [29] [4]. This discrepancy highlights flow cytometry's superior sensitivity in detecting subtle cellular changes under pronounced cytotoxic stress. Despite these differences, a strong correlation between both techniques was observed (r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001), validating fluorescence microscopy as a reliable screening tool while establishing flow cytometry as the more sensitive methodology for detailed apoptosis mechanism studies [33] [29].

Table 2: Apoptosis Detection Performance in Bioactive Glass Cytotoxicity Study

| Measurement | Flow Cytometry | Fluorescence Microscopy | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Detection Range | 0.2% - 97% [33] [29] | 9% - 97% [33] [29] | SAOS-2 cells, BG particles <38μm at 100 mg/mL |

| Cell Death Pathway Resolution | Distinguishes early apoptosis, late apoptosis, and necrosis [33] [4] | Primarily distinguishes viable vs. nonviable cells [33] | Multiparametric staining vs. FDA/PI |

| Statistical Correlation | r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001 [33] [29] | r = 0.94, R² = 0.8879, p < 0.0001 [33] [29] | Comparative analysis across all test conditions |

| Precision Under High Cytotoxic Stress | Superior precision and sensitivity [33] [4] | Reduced precision under extreme conditions [33] | High particle concentrations and small sizes |

Clinical Diagnostic Applications

In clinical diagnostics, flow cytometry has established an indispensable role for numerous applications, particularly in hematological malignancies and immunodeficiency diseases. For immunophenotyping of peripheral blood cells, flow cytometry can detect abnormal cells with marker patterns characteristic of specific leukemia and lymphoma types [34]. The DHR (dihydrorhodamine) test, used since 1988, leverages flow cytometry to assess neutrophil function by measuring their respiratory burst capacity after stimulation, enabling diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease and other functional immune disorders [34]. Flow cytometry also facilitates CD4+ T-cell counting in HIV patients, residual disease detection in cancer, and stem cell enumeration for transplantation medicine [2] [34].

Fluorescence microscopy maintains important roles in clinical diagnostics, particularly in histopathology, cytology, and infectious disease identification. Its ability to provide morphological context complements the quantitative data from flow cytometry. In autoimmune disease diagnostics, fluorescent antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing using microscopy remains a gold standard. However, for high-volume routine testing requiring precise quantification of cellular markers, flow cytometry's throughput, standardization capabilities, and quantitative output make it preferred for many clinical applications [34]. Emerging technologies like imaging flow cytometry aim to bridge these approaches by combining the high-throughput quantitative capabilities of flow cytometry with the morphological information of microscopy [8].

Decision pathway for selecting between flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy in clinical applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Flow Cytometry Viability Protocol

The following protocol summarizes the multiparametric staining approach used in the bioactive glass cytotoxicity study [33], which enabled distinction of viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cell populations:

Cell Preparation: Harvest SAOS-2 osteoblast-like cells after treatment with particulate biomaterials and prepare single-cell suspension in appropriate buffer.

Staining Cocktail Preparation: Combine the following reagents in staining buffer:

- Hoechst dye (nuclear staining)

- DiIC1 (membrane potential indicator)

- Annexin V-FITC (phosphatidylserine exposure detection)

- Propidium Iodide (PI) (membrane integrity indicator)

Staining Procedure: Incubate cell suspension with staining cocktail for 15-20 minutes at room temperature protected from light.

Data Acquisition: Analyze samples using flow cytometer with appropriate laser and filter configurations:

- Hoechst: UV laser (355 nm), 450/50 nm filter

- FITC: Blue laser (488 nm), 530/30 nm filter

- DiIC1: Red laser (640 nm), 670 nm filter

- PI: Blue laser (488 nm), 585/42 nm filter

Analysis Strategy:

- Gate on single cells using FSC-A vs FSC-H

- Identify viable cells (Hoechst+, Annexin V-, PI-)

- Identify early apoptotic cells (Hoechst+, Annexin V+, PI-)

- Identify late apoptotic/necrotic cells (Hoechst+, Annexin V+, PI+)

This protocol provides comprehensive information about cell death mechanisms beyond simple viability assessment and can be adapted for various cell types and experimental conditions.

Fluorescence Microscopy Viability Protocol

The fluorescence microscopy protocol from the same comparative study [33] utilized FDA/PI staining for viability assessment:

Cell Preparation: Culture SAOS-2 cells on appropriate substrate and treat with test particulates. Do not trypsinize; image adherent cells directly.

Staining Solution Preparation:

- Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) stock solution: 5 mg/mL in acetone

- Propidium iodide (PI) stock solution: 1 mg/mL in PBS

- Working solution: Combine FDA (final concentration 10 μg/mL) and PI (final concentration 15 μg/mL) in culture medium or buffer

Staining Procedure:

- Remove culture medium from cells

- Add staining solution to cover cells

- Incubate for 5-10 minutes at 37°C protected from light

- Remove staining solution and replace with fresh buffer

Image Acquisition:

- Use fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets

- FDA (viable cells): FITC filter set (excitation 480/30 nm, emission 535/45 nm)

- PI (dead cells): TRITC filter set (excitation 540/25 nm, emission 605/55 nm)

- Capture multiple non-overlapping fields for statistical relevance (minimum 5-10 fields)

Analysis and Quantification:

- Count FDA-positive (green, viable) and PI-positive (red, dead) cells

- Calculate viability percentage: (viable cells/total cells) × 100

- Document morphological features of cells

This approach provides direct visualization of cell status and morphology but offers limited mechanistic information compared to the multiparametric flow cytometry approach.

Research Reagent Solutions

The selection of appropriate reagents is crucial for successful cell viability assessment using either flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. The following table summarizes key reagents and their applications in viability and cell death assessment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Viability Assessment

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viability Dyes | Propidium Iodide (PI), 7-AAD | Membrane integrity indicators; exclude from viable cells [35] | PI suitable for both FCM and FM; 7-AAD preferred for FCM with FITC conjugates [35] |

| Apoptosis Detectors | Annexin V conjugates | Binds phosphatidylserine exposed on apoptotic cells [33] [29] | Requires calcium-containing buffer; typically combined with viability dye [33] |

| Metabolic Activity Indicators | Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA), Calcein-AM | Converted to fluorescent products by esterases in viable cells [33] [4] | FDA for FM; Calcein-AM for FCM; indicate enzymatic activity [33] |

| Nuclear Stains | Hoechst dyes, DAPI | Bind DNA; indicate cell presence and nuclear morphology [33] | Distinguish nucleated cells; cell cycle analysis [33] |

| Membrane Potential Sensors | DiIC1(5) | Mitochondrial membrane potential indicator [33] [29] | Loss of signal indicates early apoptosis; FCM applications [33] |

| Antibody Panels | CD markers, lineage-specific antibodies | Cell surface and intracellular protein detection [32] [34] | Multiparametric immunophenotyping; requires titration and compensation [34] |

Technical Advantages and Limitations

Flow Cytometry Strengths and Constraints