Persistent Gait Deficits After Ankle Fracture Surgery: A Systematic Comparative Analysis of Spatiotemporal Parameters, Muscle Function, and Rehabilitation Efficacy

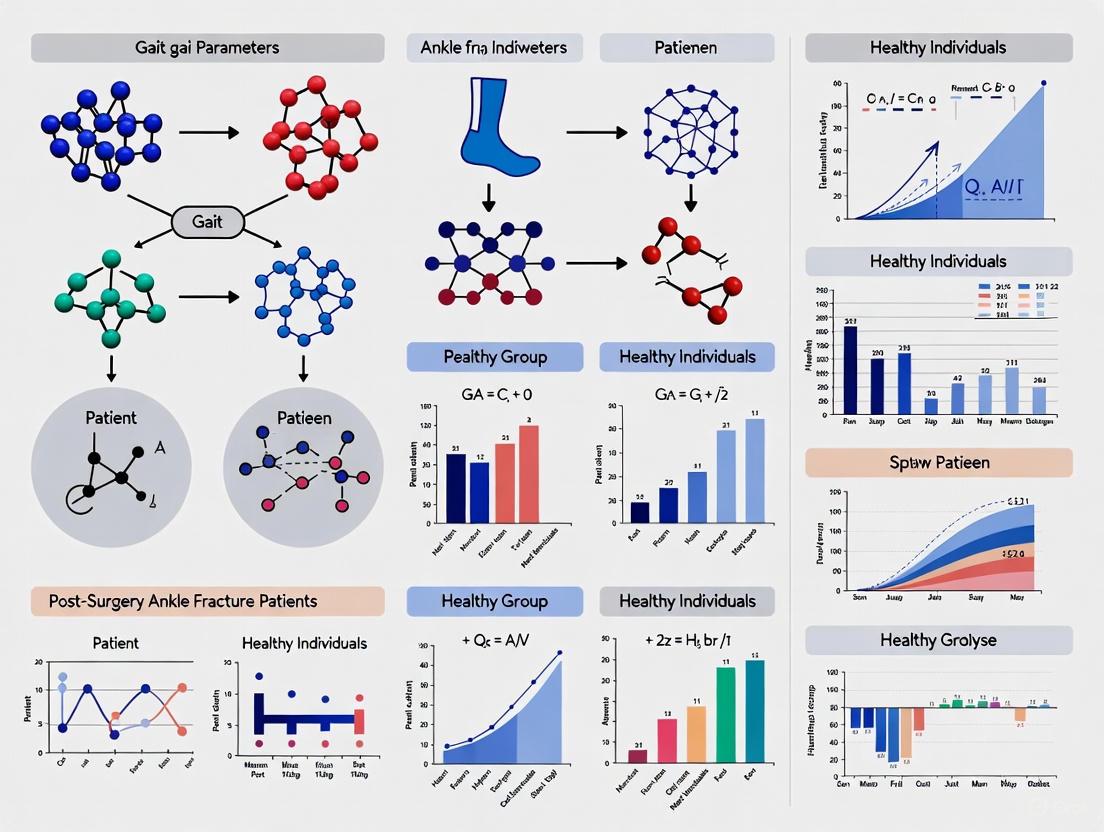

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence comparing gait parameters, muscle strength, and functional outcomes between post-surgery ankle fracture patients and healthy individuals.

Persistent Gait Deficits After Ankle Fracture Surgery: A Systematic Comparative Analysis of Spatiotemporal Parameters, Muscle Function, and Rehabilitation Efficacy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence comparing gait parameters, muscle strength, and functional outcomes between post-surgery ankle fracture patients and healthy individuals. Drawing upon recent systematic reviews and primary clinical studies, we analyze persistent deficits in spatiotemporal parameters including walking speed, step length, single support time, and cadence. We further explore methodological approaches for gait assessment, identify key rehabilitation challenges, and evaluate the efficacy of current intervention strategies. This analysis is particularly relevant for researchers and clinical professionals developing targeted rehabilitation protocols and pharmaceutical interventions aimed at optimizing functional recovery and addressing long-term mobility impairments following surgical fixation of ankle fractures.

Quantifying Persistent Gait Impairments: A Meta-Analysis of Post-Operative Ankle Fracture Recovery

Spatiotemporal gait parameters—walking speed, step length, and cadence—serve as crucial biomarkers for assessing locomotor function and rehabilitation outcomes across diverse patient populations. Within clinical research and practice, quantitative gait analysis provides an objective framework for evaluating functional recovery following surgical interventions. This meta-analysis systematically examines spatiotemporal gait deficits in post-surgery ankle fracture patients compared to healthy individuals, contextualizing these findings within the broader landscape of gait alterations associated with various physiological and cognitive challenges. The establishment of definitive normative values across age groups and pathologies enables more precise clinical assessments and facilitates targeted therapeutic interventions to restore optimal gait function.

Comparative Analysis of Gait Parameters

Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients vs. Healthy Controls

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 12 studies comprising 219 postoperative ankle fracture patients and 192 healthy controls revealed significant impairments across multiple spatiotemporal gait parameters [1]. Despite surgical intervention and subsequent rehabilitation, patients consistently failed to regain pre-injury levels of locomotor function, exhibiting characteristic alterations in their gait patterns.

Table 1: Gait Parameter Deficits in Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients

| Gait Parameter | Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking Speed (m/s) | -0.13 | [-0.45, -0.16] | < 0.001 | Significant |

| Step Length (m) | -0.15 | [-0.18, -0.12] | < 0.001 | Significant |

| Cadence (steps/min) | -8.44 | [-10.87, -6.01] | < 0.001 | Significant |

| Single Support Time (%) | -16.59 | [-19.18, -14.00] | < 0.001 | Significant |

| Peak Dorsiflexion Angular Velocity (°/s) | -7.93 | [-13.45, -2.41] | 0.005 | Significant |

| Peak Plantarflexion Angular Velocity (°/s) | -49.64 | [-99.98, 0.71] | 0.053 | Not Significant |

The meta-analysis further indicated that both muscle strength and plantar pressure were notably reduced in postoperative patients, contributing to the observed gait alterations. The persistence of these deficits highlights the complex nature of functional recovery beyond mere bone healing, emphasizing the need for targeted rehabilitation protocols addressing neuromuscular control and proprioception [1].

Contextualizing Gait Deficits Across Populations and Conditions

To properly contextualize the gait deficits observed in ankle fracture patients, it is instructive to compare these findings with other populations experiencing locomotor challenges. Spatiotemporal parameters vary considerably across pathological conditions, age groups, and challenging circumstances such as dual-task walking.

Table 2: Comparative Gait Alterations Across Populations and Conditions

| Population/Condition | Walking Speed | Step/Stride Length | Cadence | Other Key Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texting While Walking [2] | Significant decrease | Significant decrease | Significant decrease | Increased double support time, reduced single support |

| Visual Impairment [3] | Slower | Shorter stride length | Decreased | Increased step width, prolonged double support, reduced single support |

| Aging (>60 years) [4] | Progressive decline | Reduced stride length | Variable trends | Increased gait variability and asymmetry |

| Frailty/Pre-frailty [5] | Slower | Shorter steps | Reduced | Longer stride times, fragmented walking patterns |

| Parkinson's Disease [6] | - (8-11)% | - (7-17)% | -6% | +76% stride time variability, +24% double support time |

The comparative analysis reveals that ankle fracture patients share several gait characteristics with other populations experiencing mobility challenges, particularly in terms of reduced speed and step length. However, the magnitude and specific pattern of deficits may serve as distinctive biomarkers for this population, potentially guiding more targeted rehabilitation approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Gait Assessment Protocols

The primary meta-analysis on ankle fracture patients employed rigorous methodology in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines [1]. Literature searches were conducted across multiple databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science) up to February 2024, using PICOS criteria for study selection. Eligible studies included cross-sectional and non-randomized observational designs comparing gait analysis outcomes, muscle strength, and plantar pressure between postoperative ankle fracture patients and healthy controls.

Quality assessment was performed using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) tool for cross-sectional studies and the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) for observational studies [1]. Meta-analytical procedures included calculation of weighted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals, with heterogeneity assessed using Cochrane's Q test and I² statistic. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the leave-one-out method to evaluate the robustness of the findings.

Emerging Methodologies in Gait Analysis

Recent advances in gait assessment methodologies have expanded beyond traditional laboratory-based systems toward more accessible technologies:

Markerless Motion Capture Systems: Theia3D represents an emerging markerless motion capture technology that uses synchronized video data and deep learning algorithms to estimate three-dimensional human pose without skin-mounted markers [7]. Validation studies demonstrate excellent agreement with marker-based systems for gait speed (mean difference: 0.00 m/s) and good to excellent agreement for distance-based parameters, though timing parameters like stance duration showed wider limits of agreement [7].

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs): Wearable sensors containing accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers enable gait assessment in ecological settings beyond laboratory constraints. IMU measurements have been validated against laboratory analysis techniques (r > 0.83) and can capture free-living gait in community settings [6]. Normative databases have been established using sternum-placed IMUs during 50-meter walks, demonstrating consistent age-related declines in gait speed [6].

Computer Vision Approaches: Open-source pose estimation algorithms like MediaPipe enable gait analysis from standard video footage, making assessment possible in resource-limited settings [8]. This approach uses deep convolutional neural networks trained on extensive image datasets to extract body landmarks from 2D video, facilitating the calculation of stability parameters such as the Margin of Stability (MoS) in older adults [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Gait Analysis

Table 3: Essential Materials and Technologies for Gait Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| GAITRite Electronic Walkway [9] | Gold standard for spatiotemporal parameter assessment | Portable pressure-sensitive walkway; Validated for step length, velocity, cadence, and timing parameters |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) [6] [5] | Wearable sensor for laboratory and free-living gait assessment | Triaxial accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer; Enables long-term monitoring in ecological settings |

| Markerless Motion Capture (Theia3D) [7] | 3D human pose estimation without physical markers | Uses deep learning algorithms; Eliminates marker placement artifacts; Suitable for non-laboratory environments |

| OptoGait System [10] | Optical measurement system for gait parameters | Photoelectric cell-based; Synchronizes with video recording; Provides comprehensive spatiotemporal data |

| MediaPipe Pose [8] | Open-source pose estimation framework | Markerless 2D/3D pose estimation from video; Accessible for resource-limited settings |

| Health&Gait Dataset [10] | Video-based gait analysis dataset | 1,564 videos from 398 participants; Includes anthropometric data and gait parameters |

Standardized Assessment Protocols

10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT): A clinically accessible assessment demonstrating high test-retest reliability for measuring comfortable and fast gait speed (ICC = 0.95-0.96) and step length (ICC = 0.91-0.98) in adolescents and adults with brain injury [9]. This test shows fair-to-moderate agreement with GAITRite during comfortable walking speeds (ICC = 0.46-0.89) and high agreement during maximal walking speeds (ICC = 0.91-0.96) [9].

Dual-Task Paradigms: Assessment of gait while performing concurrent cognitive tasks (e.g., visuospatial memory tasks) [9]. This approach detects deficits that may not manifest during single-task walking, particularly relevant for concussion management and neurodegenerative conditions [2] [9].

Six-Minute Walk Test: Used in datasets like DUO-GAIT to assess endurance and gait patterns under prolonged walking conditions, sometimes combined with cognitive tasks to evaluate dual-task costs [10].

This meta-analysis establishes that postoperative ankle fracture patients exhibit significant deficits in walking speed, step length, and cadence compared to healthy controls, with weighted mean differences of -0.13 m/s, -0.15 m, and -8.44 steps/minute, respectively [1]. These impairments persist despite surgical intervention and rehabilitation, highlighting the complex nature of functional recovery that extends beyond bone healing to encompass neuromuscular control and proprioceptive function.

The contextualization of these findings within the broader landscape of gait alterations reveals common patterns across diverse populations, suggesting possible shared mechanisms in the neural control of locomotion under challenging conditions. Emerging methodologies in gait assessment, particularly markerless motion capture and wearable sensors, offer promising avenues for more ecological monitoring of recovery trajectories and rehabilitation efficacy.

For researchers and clinicians, these findings underscore the importance of comprehensive gait assessment using validated technologies and standardized protocols. The establishment of definitive normative values and pathological patterns enables more precise evaluation of interventions aimed at restoring optimal locomotor function in postoperative patients and other populations experiencing mobility challenges.

The following tables synthesize quantitative findings from a 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis, which encompassed 12 studies comparing 219 post-surgery ankle fracture patients with 192 healthy controls [1] [11].

Table 1: Gait Parameter Alterations Post-Ankle Fracture Surgery

| Gait Parameter | Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) vs. Healthy Controls | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking Speed | -0.13 m/s | [-0.45, -0.16] | < 0.001 |

| Step Length | -0.15 m | [-0.18, -0.12] | < 0.001 |

| Cadence | -8.44 steps/min | [-10.87, -6.01] | < 0.001 |

| Single Support Time | -16.59 % | [-19.18, -14.00] | < 0.001 |

| Peak Dorsiflexion Angular Velocity | -7.93 °/s | [-13.45, -2.41] | 0.005 |

| Peak Plantarflexion Angular Velocity | -49.64 °/s | [-99.98, 0.71] | 0.053 (NS) |

NS: Not Statistically Significant

Table 2: Muscle Strength and Plantar Pressure Deficits

| Measured Parameter | Post-Surgery Alteration | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Torque (Dorsiflexion) | Significantly Reduced [1] | Major contributor to impaired gait. |

| Peak Torque (Plantarflexion) | Significantly Reduced [1] | Impacts push-off power during walking. |

| Plantar Pressure | Notable Reduction [1] | Altered distribution and magnitude. |

| Overall Functional Recovery | Incomplete [1] | Patients often fail to regain pre-injury levels of walking speed, muscle strength, and normal plantar pressure distribution despite rehabilitation. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The comparative data are derived from standardized experimental protocols designed to objectively quantify functional deficits.

Gait Analysis Protocol

- Objective: To quantify spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters in a controlled environment [1].

- Equipment: Three-dimensional motion analysis systems with synchronized camera and force plate technology [1] [12].

- Procedure: Participants walk at a self-selected speed along a walkway. Data from multiple gait cycles are captured, focusing on the sagittal plane kinematics of the ankle joint [1].

- Measured Variables: Walking speed, step length, cadence, single-limb support time, and peak angular velocities for dorsiflexion and plantarflexion during specific gait phases [1].

Muscle Strength Assessment Protocol

- Objective: To measure the isometric and/or isokinetic strength of ankle dorsiflexor and plantarflexor muscle groups [1].

- Equipment: Isokinetic dynamometer [1].

- Procedure: The participant's foot is securely fastened to the dynamometer's footplate. They perform maximal voluntary contractions against resistance through the ankle's full range of motion, typically in a seated position with knee flexed [1].

- Primary Outcome: Peak torque, which is the highest torque output produced during the movement, measured in Newton-meters (Nm). This is a direct indicator of muscle functional capacity [1].

Plantar Pressure Measurement Protocol

- Objective: To assess the distribution and magnitude of pressure across the plantar surface of the foot during standing and walking [1].

- Equipment: Pressure sensor platforms (e.g., Novel emed) or in-shoe sensor insoles (e.g., Novel pedar). The 2025 meta-analysis highlighted the use of such systems [1] [13].

- Procedure: Participants perform barefoot walking trials, stepping onto the pressure platform. For in-shoe analysis, flexible sensor sheets are placed inside the subject's footwear to capture data during prolonged activity [13].

- Data Processing & Analysis: Software algorithms process the raw sensor data to generate metrics such as peak pressure (maximum pressure under any sensor), mean pressure, pressure-time integral (the cumulative load over time), and contact area. The use of open-source tools like the

pressuReR package allows for standardized processing and regional mask analysis (e.g., separating heel, midfoot, forefoot) [13]. - Key Metric: Peak Plantar Pressure is a critical variable for identifying areas of high loading risk and understanding altered biomechanics [1] [13].

Experimental Workflow and Logical Relationships

The diagram below illustrates the structured pathway from patient recruitment to data synthesis in comparative post-surgery research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Biomechanical Research

| Item | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Isokinetic Dynamometer | Hardware | The gold-standard instrument for objectively quantifying peak torque and muscle endurance of ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors [1]. |

| Pressure Measurement Platform | Hardware | A rigid plate embedded with sensor arrays to capture dynamic barefoot plantar pressure distribution during gait [1] [13]. |

| In-Shoe Pressure Insoles | Hardware | Flexible sensor sheets placed inside footwear to measure plantar pressure distribution over multiple steps in real-world conditions [13] [14]. |

| 3D Motion Capture System | Hardware | A multi-camera system used for high-precision kinematic analysis of joint angles and spatiotemporal gait parameters [1] [12]. |

pressuRe R Package |

Software | An open-source tool for standardizing the processing, analysis, and visualization of plantar pressure data from various hardware systems, promoting reproducibility [13]. |

| Self-Administered Foot Evaluation Questionnaire (SAFE-Q) | Patient-Reported Outcome | A validated instrument to assess quality of life and function from the patient's perspective, covering pain, daily living, and social functioning [12]. |

| 2-(Diethylamino)ethyl (3-(octyloxy)phenyl)carbamate hydrochloride | 2-(Diethylamino)ethyl (3-(octyloxy)phenyl)carbamate hydrochloride, CAS:32223-82-8, MF:C21H37ClN2O3, MW:401.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SI-2 | SI-2, MF:C15H15N5, MW:265.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Ankle fractures represent one of the most common lower limb fractures worldwide, with increasing incidence particularly among individuals over 50 years of age [15] [16]. While surgical intervention successfully achieves fracture union in most cases, a growing body of evidence indicates that anatomical healing does not necessarily translate to functional recovery. This comparative analysis examines the persistent functional deficits observed in patients at 4.5 years post-surgery, comparing their gait parameters, muscle strength, and functional performance against healthy control subjects. Understanding these long-term limitations is crucial for researchers and clinicians aiming to develop more effective rehabilitation protocols and outcome measures that extend beyond radiographic healing.

Comparative Analysis of Gait Parameters and Functional Outcomes

Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters: Patients vs. Healthy Controls

Table 1: Comparative analysis of spatiotemporal gait parameters between post-surgery ankle fracture patients and healthy individuals

| Gait Parameter | Post-Surgery Patients | Healthy Controls | Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking speed (m/s) | Reduced | Normal | -0.13 (95% CI: -0.45, -0.16) | <0.001 |

| Step length (m) | Shorter | Normal | -0.15 (95% CI: -0.18, -0.12) | <0.001 |

| Single support time (%) | Reduced | Normal | -16.59 (95% CI: -19.18, -14.00) | <0.001 |

| Cadence (steps/min) | Lower | Normal | -8.44 (95% CI: -10.87, -6.01) | <0.001 |

| Peak dorsiflexion angular velocity (°/s) | Impaired | Normal | -7.93 (95% CI: -13.45, -2.41) | 0.005 |

| Peak plantarflexion angular velocity (°/s) | Lower | Normal | -49.64 (95% CI: -99.98, 0.71) | 0.053 |

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 12 studies comprising 219 postoperative ankle fracture patients and 192 healthy controls revealed significant impairments across multiple gait parameters [11] [17]. Despite surgical intervention and subsequent rehabilitation, patients failed to regain pre-injury levels of walking speed, step length, and cadence. The most pronounced differences were observed in single support time and walking speed, indicating fundamental alterations in gait mechanics that persist long after fracture healing [11].

Functional Performance and Clinical Outcomes

Table 2: Long-term functional outcomes after ankle fracture surgery (4.5-year follow-up)

| Functional Measure | Surgical Side | Non-Surgical Side | P-value | Clinical Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heel Rise Test (cm) | Significant deficit | Normal | 0.020 | - |

| Weight-Bearing Lunge Test (cm) | Significant deficit | Normal | 0.006 | - |

| AOFAS Ankle-Hindfoot Scale | - | - | - | 86.5 |

| Olerud-Molander Ankle Score (OMAS) | - | - | - | 80 |

At a mean follow-up of 4.5 years post-surgery, patients demonstrated significant functional limitations despite favorable clinical scores [15] [16]. The Heel Rise Test, which assesses ankle plantarflexion strength, and the Weight-Bearing Lunge Test (WBLT), which evaluates ankle dorsiflexion mobility, both showed substantial deficits on the surgical side compared to the non-surgical side. This discrepancy between objective functional measures and clinical scoring systems highlights the limitation of relying solely on questionnaire-based outcomes for evaluating recovery [15].

The long-term nature of these deficits is further corroborated by a 5-year follow-up study which found that 63% of patients still complained of stiffness, 45% reported ankle swelling, and 50% experienced persistent pain [18]. Additionally, 39% of patients felt they had not fully recovered, and 38% did not return to their pre-injury sporting activities [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Gait Analysis Protocol

The experimental assessment of gait parameters followed standardized protocols across multiple studies. Spatiotemporal gait parameters were evaluated using the GAITRite system, an electronic walkway mat that captures precise measurements of various gait components [15] [16]. Participants walked barefoot along a 6-meter walkway three times at their normal walking speed, with trials starting 2 meters before the walkway to ensure consistent velocity upon entry [16].

Specific measured parameters included:

- Step time and step length

- Stride length

- Base of support

- Single and double support time

- Walking speed

- Cadence

Data analysis was performed using statistical packages such as SPSS, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) calculated to determine inter-trial reliability [16]. Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) and Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) values were established to ensure measurement precision.

Functional Performance Testing

Two key functional tests were administered to assess specific ankle functions:

Heel Rise Test Protocol:

- Participants performed repeated unilateral heel lifts while standing

- Total heel rise height was measured in centimeters

- The test primarily assesses plantarflexion strength and endurance [15] [16]

Weight-Bearing Lunge Test (WBLT) Protocol:

- Participants performed a forward lunge with the tested foot flat on the ground

- Maximum distance from the great toe to the wall was measured while maintaining heel contact

- This test specifically evaluates weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion range of motion [15] [16]

Both tests demonstrated excellent intrarater reliability, with ICC values of 0.98 for the Heel Rise Test and 0.99 for the WBLT, confirming their suitability for longitudinal assessment [15].

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and equipment for ankle fracture recovery studies

| Research Tool | Specific Function | Application in Ankle Fracture Research |

|---|---|---|

| GAITRite Electronic Walkway | Captures spatiotemporal gait parameters | Quantitative assessment of walking speed, step length, cadence, and support times [15] [16] |

| Isokinetic Dynamometer | Measures peak torque of dorsiflexion and plantarflexion | Objective evaluation of ankle muscle strength deficits [11] [17] |

| Pressure Platform System | Assesses plantar pressure distribution | Analysis of weight-bearing patterns and pressure abnormalities [11] |

| AOFAS Ankle-Hindfoot Scale | Patient-reported clinical outcome measure | Subjective assessment of pain, function, and alignment [15] [16] |

| Olerud-Molander Ankle Score (OMAS) | Disease-specific functional rating | Evaluation of daily activity performance and symptom severity [15] [18] |

| Weight-Bearing Lunge Test Apparatus | Measures ankle dorsiflexion range of motion | Assessment of joint stiffness and mobility restrictions [15] [16] |

| PPHP | PPHP Polypropylene Homopolymer Resin | |

| kn-92 | kn-92, CAS:176708-42-2, MF:C24H25ClN2O3S, MW:457 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence from 4.5-year follow-up studies demonstrates conclusively that ankle fracture patients experience persistent functional deficits long after radiographic union has been achieved. These limitations manifest as altered gait patterns, reduced muscle strength, impaired range of motion, and functional performance deficits, despite seemingly favorable clinical scores. The discrepancy between objective functional measures and subjective clinical outcomes underscores the need for more sophisticated assessment protocols in both clinical and research settings. Future research should focus on developing targeted rehabilitation strategies that address the specific soft tissue mobility and muscle function impairments identified in these long-term studies, with the goal of restoring pre-injury functional levels rather than merely achieving fracture healing.

The successful recovery of motor function following ankle fracture surgery does not always equate to a successful quality of life (QOL) outcome from the patient's perspective. This guide provides a comparative analysis of objective gait parameters and their correlation with patient-reported outcomes, specifically the Self-Administered Foot Evaluation Questionnaire (SAFE-Q). It synthesizes current research to help professionals in drug development and clinical research understand how weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion and gait speed serve as critical biomarkers for patient recovery and QOL, providing a framework for evaluating rehabilitation interventions and therapeutic outcomes.

Comparative Analysis of Key Parameters

Gait Parameters: Patients vs. Healthy Norms

Post-surgical ankle fracture patients demonstrate significant deficits in gait parameters when compared to healthy individuals. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from meta-analyses and comparative studies.

Table 1: Gait Parameter Comparison Between Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients and Healthy Individuals

| Gait Parameter | Post-Surgery Patients | Healthy Individuals (Normative Data) | Statistical Significance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walking Speed | Slower | ~1.34 m/s (comfortable pace) [19] | P < 0.001 [11] | Systematic Review [11] |

| Cadence | Significantly lower (WMD: -8.44 steps/min) [11] | 90-120 steps/min [19] | P < 0.001 [11] | Systematic Review [11] |

| Step Length | Shorter (WMD: -0.15 m) [11] | ~70 cm [19] | P < 0.001 [11] | Systematic Review [11] |

| Single Support Time | Significantly reduced (WMD: -16.59) [11] | Not Reported | P < 0.001 [11] | Systematic Review [11] |

| Peak Dorsiflexion Angular Velocity | Significantly lower (WMD: -7.93) [11] | Not Reported | P = 0.005 [11] | Systematic Review [11] |

Abbreviation: WMD, Weighted Mean Difference.

Correlations with SAFE-Q Quality of Life Domains

The functional impairments detailed in Table 1 have a direct and measurable impact on patient quality of life, as quantified by the SAFE-Q questionnaire. The SAFE-Q is a validated, region-specific patient-reported outcome measure with high test-retest reliability (ICC >0.7 for all subscales) [20] [21]. It evaluates QOL across multiple subscales, each scored from 0 (least healthy) to 100 (healthiest) [22] [20].

Table 2: Correlation of Physical Factors with SAFE-Q Subscales in Post-Operative Ankle Fracture Patients

| Physical Factor | SAFE-Q Subscale | Statistical Correlation | Clinical Interpretation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight-Bearing Ankle Dorsiflexion ROM (Deep Squat Sitting) | Pain and Pain-Related | β = 0.584, P < 0.001 [22] | Strong, positive association; greater ROM linked to less pain. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] |

| Physical Functioning and Daily Living | β = 0.376, P = 0.006 [22] | Moderate, positive association; greater ROM linked to better physical function. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] | |

| Social Functioning | β = 0.317, P = 0.045 [22] | Moderate, positive association; greater ROM linked to improved social activity. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] | |

| General Health and Well-Being | β = 0.483, P = 0.005 [22] | Moderate to strong, positive association; greater ROM linked to better overall well-being. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] | |

| Gait Speed | Physical Functioning and Daily Living | β = 0.555, P < 0.001 [22] | Strong, positive association; faster speed linked to better daily function. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] |

| Social Functioning | β = 0.514, P = 0.002 [22] | Strong, positive association; faster speed linked to improved social activity. | Cross-Sectional Study [22] |

Abbreviations: ROM, Range of Motion; β, Standardized Partial Regression Coefficient.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Measuring the Key Variables

Weight-Bearing Ankle Dorsiflexion Protocol

The association with QOL is particularly strong for weight-bearing dorsiflexion measurements, which better replicate the demands of daily life than non-weight-bearing tests [22].

- Objective: To quantify weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) using methods that correlate with quality of life.

- Equipment: Standard goniometer.

- Methodologies:

- Rear Ankle with Knee Extended: The participant steps forward with the non-measured leg and leans the lower leg of the measured side forward as far as possible, keeping the knee extended and the heel on the ground. The angle is measured between a perpendicular line to the floor and a line connecting the fibular head and lateral malleolus [22].

- Rear Ankle with Knee Flexed: The same as above, but performed with the knee of the measured side flexed during a forward lunge [22].

- Front Ankle during Forward Lunge: The participant steps forward with the lower leg being measured and leans forward in a lunge position against a wall for balance [22].

- Deep Squat Sitting: The participant squats to the deepest position they can maintain for 3 seconds, keeping the heels on the ground and arms extended forward parallel to the floor. The goniometer is used to measure the ankle angle in this position [22]. This specific method was identified as an independent variable for all four primary SAFE-Q subscales [22].

- Data Collection: Measurements are repeated twice for each method to ensure reliability. The minimum value is 1° [22].

Gait Analysis Protocol

- Objective: To obtain spatiotemporal gait parameters such as velocity, cadence, and step length.

- Equipment: Three-dimensional motion analyzer [22] or an electronic walkway system (e.g., GAITRite) [23] [24]. For clinical settings, a stopwatch and measured walkway can be used for speed and cadence.

- Procedure: Participants complete multiple walks at their self-selected, comfortable walking speed. Walks are initiated and terminated a meter before and after the walkway to account for acceleration and deceleration, ensuring data is collected at a constant velocity [23].

- Key Parameters: The software typically calculates gait speed (m/s), cadence (steps/min), step length (m), stride length (m), and single/double support times (s or % of gait cycle) automatically [19] [23].

Patient-Reported Outcome Measure: SAFE-Q

- Instrument: The Self-Administered Foot Evaluation Questionnaire (SAFE-Q) version 2 [20] [21].

- Administration: Patients complete the 34-item questionnaire independently. Items are scored on a Likert scale (0-4) or a visual analog scale (for specific questions) [22].

- Scoring: Scores for each of the five core subscales (Pain and Pain-Related, Physical Functioning and Daily Living, Social Functioning, Shoe-Related, and General Health and Well-Being) are calculated and scaled from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) [22] [20]. The Sports Activity subscale is optional.

The logical relationship between these protocols and the core findings of the research is summarized in the workflow below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and instruments required for conducting research in this field, based on the methodologies cited in the reviewed literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Gait and QOL Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| SAFE-Q Questionnaire | A validated, patient-reported outcome measure to assess foot- and ankle-specific health-related quality of life. It provides subscale scores for pain, physical function, social function, and general well-being [22] [20]. | The primary QOL metric in recent studies correlating physical function with life impact [22]. |

| Three-Dimensional Motion Analysis System | The gold standard for comprehensive gait analysis, using multiple cameras and reflective markers to capture detailed kinematic and kinetic data during walking [22]. | Used to measure gait parameters in experimental settings [22]. |

| Electronic Walkway (e.g., GAITRite) | A portable system with pressure-sensitive sensors that automatically calculates spatiotemporal gait parameters (speed, cadence, step length, etc.) as a subject walks across it [23] [24]. | Used for efficient and reliable gait data collection in lab and clinical environments [23] [24]. |

| Isokinetic Dynamometer (e.g., Biodex) | An instrument used to objectively measure muscle strength (peak torque) of ankle plantarflexors and dorsiflexors under controlled conditions and velocities [22]. | Used to assess ankle strength as a physical factor post-surgery [22]. |

| Standard Goniometer | A simple, low-cost tool for measuring joint range of motion. Essential for assessing weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion [22]. | The tool specified for measuring all ankle dorsiflexion ROM in the cited study [22]. |

| T2AA | T2AA, CAS:1380782-27-3, MF:C15H15I2NO3, MW:511.09 | Chemical Reagent |

| PX 2 | PX 2, MF:C22H25FN4O2, MW:396.5 | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion and Path Forward

The evidence clearly demonstrates that gait speed and weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion ROM, particularly in a functional position like a deep squat, are not just performance metrics but are significant biomarkers for patient-reported quality of life after ankle fracture surgery [22]. The strong, independent correlations with multiple SAFE-Q subscales underscore that rehabilitation programs must target the restoration of these specific functions to achieve meaningful patient outcomes.

Future research should focus on developing and testing targeted rehabilitation interventions designed to improve weight-bearing dorsiflexion and gait speed. Furthermore, the integration of these objective measures with validated patient-reported outcomes like the SAFE-Q provides a robust framework for evaluating new pharmacological adjuvants or physical therapies in clinical trials, ensuring that treatments are assessed against metrics that truly matter to patients' lives.

Advanced Gait Analysis Methodologies: From Laboratory Systems to Clinical Applications

The quantitative analysis of human gait is indispensable in clinical diagnostics, rehabilitation monitoring, and biomedical research. Following surgical interventions such as ankle fracture repair, gait analysis provides objective data to evaluate functional recovery and compare patient outcomes to healthy baseline performance [1] [11]. Multiple technologies are available for capturing spatiotemporal gait parameters, ranging from sophisticated laboratory-based systems to portable clinical tools and consumer-grade devices. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three prominent approaches: laboratory-grade 3D motion analysis systems, electronic walkways like the GAITRite system, and smartphone applications. Framed within research comparing post-surgery ankle fracture patients to healthy individuals, this comparison evaluates each tool's performance characteristics, supported by experimental data, to inform researchers and clinicians in selecting appropriate assessment technologies.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and optimal use cases for the three primary gait assessment technologies.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Gait Assessment Technologies

| Feature | GAITRite Electronic Walkway | 3D Motion Analysis (Lab) | Smartphone Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology Type | Electronic pressure-sensitive walkway [25] | Optoelectronic systems (e.g., Vicon) with force plates [26] | Embedded inertial sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes) [27] [28] |

| Key Measured Parameters | Spatial: Step/stride length, step width [23].Temporal: Gait speed, cadence, step/stride time, stance/swing phase % [23] [25]. | Comprehensive kinematics (joint angles, velocities), kinetics (ground reaction forces), and spatiotemporal parameters [26]. | Spatiotemporal: Gait speed, cadence, step time, distance [27] [28]. |

| Validity & Reliability | High validity (ICC >0.93) and test-retest reliability for core parameters (speed, stride length, cadence) across populations [25] [29]. | Considered the gold standard for kinematic and kinetic data [26] [30]. | High agreement with GAITRite for speed & cadence (ICC 0.78-0.99) [28]. Moderate-to-excellent reliability in older adults [27]. |

| Key Strengths | High accuracy for spatiotemporal metrics; quick setup; excellent reliability; suitable for clinical environments [25]. | Comprehensive biomechanical data; gold standard for detailed movement analysis [26]. | Extreme portability and low cost; enables monitoring in free-living environments; high user acceptability [27] [28]. |

| Key Limitations | Limited capture area; measures only a few consecutive strides; cannot assess kinematics or kinetics [25]. | High cost, complex setup, and laboratory-confined; requires technical expertise [26]. | Lower accuracy for complex parameters (e.g., step asymmetry); performance varies with placement and algorithm [27] [28]. |

| Context in Ankle Fracture Research | Effectively identifies deficits in gait speed, step length, and cadence in patients vs. controls [1]. | Can reveal underlying mechanisms like reduced peak dorsiflexion angular velocity [1]. | Potential for continuous, low-cost monitoring of walking speed as a functional outcome in community settings [27]. |

Detailed Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Comparative Data in Pathological and Healthy Populations

Research on post-surgery ankle fracture patients quantitatively illustrates the sensitivity of these tools in detecting functional impairments. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies revealed that, despite rehabilitation, patients show significant deficits compared to healthy controls when assessed with instrumented systems [1] [11]. Key findings include:

- Walking Speed: Patients walked significantly slower (Weighted Mean Difference [WMD] = -0.13 m/s) [1].

- Step Length: Patients had shorter steps (WMD = -0.15 m) [1].

- Cadence: Patients exhibited a lower step rate (WMD = -8.44 steps/min) [1].

- Single Support Time: The time spent on the affected limb was reduced (WMD = -16.59%) [1].

These parameters, which are reliably captured by both GAITRite and smartphone systems, highlight the persistent gait impairments in this patient population [1] [28].

The following table synthesizes key reliability and validity metrics for the assessed technologies, as reported in the literature.

Table 2: Summary of Key Reliability and Validity Metrics

| Technology | Parameter | Metric & Population | Reported Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAITRite | Gait Speed, Stride Length, Cadence | Test-Retest Reliability (ICC) across multiple populations [25] | ICC > 0.75 |

| GAITRite | Spatial Measures | Validity vs. Paper-and-Pencil Method (ICC) [29] | ICC > 0.95 |

| GAITRite | Temporal Measures | Validity vs. Video-Based Method (ICC) [29] | ICC > 0.93 |

| Smartphone App | Walking Velocity, Cadence | Validity vs. GAITRite (ICC) in Healthy Adults [28] | ICC 0.778 - 0.999 |

| Smartphone App | Gait Speed | Validity & Reliability in Older Adults [27] | ICC ~ 0.9 |

Standardized Experimental Protocols

To ensure the validity and comparability of data, studies typically follow standardized protocols:

- GAITRite Protocol: Participants are instructed to walk at a self-selected comfortable speed across the walkway, initiating and terminating their gait several feet before and after the mat to capture steady-state walking [23]. Multiple walking trials are averaged to obtain a representative sample.

- Smartphone Assessment Protocol: The smartphone is securely attached to the participant's body, most commonly on the lower back near the sacrum (center of mass) using an elastic belt [28]. Participants then perform walking tasks, such as at preferred, slow, and fast speeds, while data is collected via a custom or commercial application [28].

- 3D Motion Analysis Protocol: Participants walk along a walkway instrumented with force plates. Reflective markers are placed on anatomical landmarks, and multiple cameras capture their trajectory. Data from the cameras and force plates are synchronized to compute joint kinematics and kinetics [26].

Gait Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for conducting a gait assessment study, from participant preparation to data interpretation, which is common across technologies but differs in the core measurement step.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key materials and tools required for conducting gait analysis research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Gait Analysis Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Walkway | Captures footfall patterns to compute spatiotemporal gait parameters in a controlled setting. | GAITRite system (CIR Systems Inc.) with an active sensor area [23] [25]. |

| 3D Motion Capture System | Provides gold-standard, comprehensive analysis of body movement in three dimensions, including joint kinematics and kinetics. | Vicon or similar optoelectronic system with infrared cameras and force plates [26]. |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Wearable sensors for capturing gait data outside the lab. Can be standalone or embedded in smartphones. | Gait Up Physilog5 [26]; Smartphone accelerometers (e.g., Samsung Galaxy S20) [28]. |

| Data Processing Software | Transforms raw sensor data into quantifiable gait metrics and facilitates statistical analysis. | GAITRite Platinum software [23]; Custom algorithms (e.g., in Visual Studio) [28]. |

| Standardized Walkway | Provides a designated, clear path for walking trials to ensure consistency across measurements. | A straight, level path of sufficient length (e.g., with 2m acceleration/deceleration zones) [28]. |

| XAC | XAC, MF:C21H28N6O4.2HCl, MW:501.41 | Chemical Reagent |

| JW67 | JW67, CAS:442644-28-2, MF:C21H18N2O6, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accurate measurement of weight-bearing ankle dorsiflexion range of motion (ROM) is a critical component in biomechanical research and clinical practice, particularly in the context of evaluating functional recovery in post-surgery ankle fracture patients. Deficits in dorsiflexion are a well-documented impairment following ankle fracture, directly impacting fundamental activities like walking, stair climbing, and squatting [31] [32]. Instrumental gait analysis has revealed that postoperative ankle fracture patients exhibit significant alterations in gait parameters, including reduced walking speed, shorter step length, and lower peak dorsiflexion angular velocity compared to healthy individuals [11] [17]. This comparative analysis examines the primary techniques for assessing weight-bearing dorsiflexion ROM, with a specific focus on their application in research comparing postoperative ankle fracture patients with healthy controls.

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Techniques

Reliability and Measurement Error of Primary Techniques

Table 1: Comparative reliability and measurement parameters of weight-bearing dorsiflexion assessment techniques

| Measurement Technique | Intrarater Reliability (ICC) | Interrater Reliability (ICC) | Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) | Minimal Detectable Change (MDC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tape Measure (Distance-to-Wall) | 0.98 - 0.99 [33] | 0.80 - 0.99 [33] | 0.4 - 0.6 cm [34] | 1.1 - 1.5 cm [34] |

| Digital Inclinometer | 0.96 - 0.97 [34] | 0.88 [34] | 1.3 - 1.4° [34] | 3.7 - 3.8° [34] |

| Standard Goniometer | 0.85 - 0.96 [34] | 0.89 [34] | 1.8 - 2.8° [34] | 5.0 - 7.7° [34] |

| Smartphone Inclinometer App | 0.72 - 0.82 [35] | 0.65 - 0.73 [35] | Not reported | Not reported |

Table 2: Functional correlates and clinical applications of dorsiflexion measurement techniques

| Technique | Equipment Requirements | Administration Time | Key Advantages | Considerations for Post-Fracture Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight-Bearing Lunge Test | Tape measure, wall [33] | 5-10 minutes | Excellent reliability, minimal equipment, functional position [33] [34] | Heel contact maintenance may be challenging in early rehabilitation; correlates with gait speed [11] |

| Inclinometer Methods | Digital inclinometer or smartphone with app [34] [35] | 5-10 minutes | Reduced alignment error, digital output [34] | Higher cost; requires tibial tuberosity palpation which may be difficult with edema |

| Goniometer | Standard goniometer [34] | 5-10 minutes | Low cost, widely available [34] | Higher technical proficiency required for alignment [34] |

| Deep Squat Assessment | Camera for video analysis (optional) [32] | 5 minutes | Assesses integrated mobility chain | May be contraindicated in early post-surgical phases |

The quantitative comparison reveals a clear hierarchy in measurement precision. The tape measure method (Weight-Bearing Lunge Test) demonstrates superior reliability coefficients and lower measurement error compared to other techniques [33] [34]. This methodological advantage is particularly relevant in the context of ankle fracture research, where the tape measure's minimal detectable change of 1.1-1.5 cm translates to approximately 4.0-5.4° of dorsiflexion (using the conversion factor of 1 cm ≈ 3.6°) [33]. This sensitivity to change is crucial for detecting clinically meaningful improvements during postoperative rehabilitation.

The functional implications of dorsiflexion limitations are substantial in ankle fracture populations. Research demonstrates that restricted dorsiflexion ROM directly correlates with altered gait patterns, including reduced walking speed, shorter step length, and decreased single-limb support time [11] [17]. These functional deficits persist long-term in a significant subset of patients, with approximately 15% reporting considerable impairment years after surgery, and those with trimalleolar fractures showing the poorest outcomes [36].

Experimental Protocols for Dorsiflexion Assessment

Weight-Bearing Lunge Test (Knee-to-Wall Test) Protocol

Purpose: To assess weight-bearing dorsiflexion range of motion in a functional position that mimics the biomechanical demands of daily activities [33].

Equipment Required: Tape measure (cm), vertical wall surface [33].

Procedure:

- Position the tape measure perpendicular to the wall, secured to the floor [33].

- Instruct the participant to stand facing the wall, barefoot or wearing minimalist shoes [32].

- The participant places the test foot with the great toe aligned at a starting position approximately 10 cm from the wall [34].

- The non-test leg is positioned comfortably or can rest on the floor for support [33].

- The participant is instructed to lunge forward, flexing the knee while keeping the heel firmly planted on the floor [33].

- The knee must move in line with the second toe throughout the movement to control for lower extremity rotation [32].

- If the knee touches the wall comfortably, the foot is moved further from the wall in 1 cm increments until the maximum distance where the knee can just touch the wall without heel lift is identified [33] [34].

- If the knee cannot touch the wall at the initial position, the foot is moved closer until contact is achieved [34].

- The maximum distance from the wall to the tip of the big toe is recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm [34].

- The process is repeated for three trials on each limb, with the average used for analysis [34].

Data Interpretation: Each centimeter of distance corresponds to approximately 3.6° of ankle dorsiflexion [33]. Normative values in healthy young adults typically range from 12-15 cm (approximately 4.5-6 inches) [32].

Considerations for Post-Surgical Assessment: In ankle fracture populations, pain or apprehension may initially limit performance. The non-weight-bearing limb can be positioned for greater support, and participants may use the wall for upper extremity support [33]. The tester should monitor for compensatory movements, particularly heel lift or foot rotation, which invalidate the measurement.

Inclinometer-Based Dorsiflexion Measurement Protocol

Purpose: To obtain direct angular measurement of tibial inclination during weight-bearing dorsiflexion.

Equipment Required: Digital inclinometer or smartphone with inclinometer application (e.g., Spirit Level Plus), wall for support [34] [35].

Procedure:

- The participant assumes the same starting position as the Weight-Bearing Lunge Test [34].

- The participant lunges forward to their maximal dorsiflexion range while maintaining heel contact [34].

- The inclinometer is placed on the distal tibia, approximately 1 cm above the most prominent point of the distal tibia [35].

- For smartphone applications, the device is positioned with its short axis along the tibial shaft [35].

- The inclinometer is zeroed to horizontal before each measurement session [34].

- The angle relative to the horizontal is recorded in degrees [34].

- Three measurements are taken for each limb, with the average used for analysis [34].

Data Interpretation: The angle represents the total dorsiflexion ROM. Normal values typically range from 35-45° in healthy adults, though significant inter-individual variation exists [32].

Technical Considerations: Digital inclinometers demonstrate excellent intrarater reliability (ICC = 0.96-0.97) and reduce measurement error compared to goniometers [34]. Smartphone applications show moderate to good reliability (ICC = 0.65-0.82), offering an accessible alternative with slightly higher measurement error [35].

Diagram 1: Weight-bearing dorsiflexion ROM assessment workflow. This flowchart illustrates the standardized procedure for assessing dorsiflexion using either tape measure or inclinometer methods, highlighting key decision points for accurate measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential equipment for weight-bearing dorsiflexion research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Measurement | Standard metric tape measure | Primary outcome for Weight-Bearing Lunge Test; distance converted to angular equivalent [33] [34] | Ensure perpendicular alignment to wall; measure to nearest 0.1 cm |

| Angular Measurement | Digital inclinometer (e.g., Acumar); Universal goniometer | Direct angular measurement of tibial inclination [34] | Digital inclinometers show higher reliability; zero device to horizontal reference |

| Digital Integration | Smartphone applications (e.g., Spirit Level Plus, TiltMeter) | Accessible alternative to dedicated inclinometers; good validity and reliability [35] | Calibrate before use; ensure consistent device placement |

| Motion Capture | 3D stereophotogrammetry; Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Gold standard for comprehensive gait analysis; captures dynamic dorsiflexion during functional tasks [31] | Requires specialized laboratory setup; provides kinematic data beyond static ROM |

| Pressure Monitoring | Pressure-sensitive walkway; In-shoe pressure systems | Assesses plantar pressure distribution during dorsiflexion; correlates with loading patterns [31] [17] | Identifies compensatory weight-shifting in pathological populations |

| Support Equipment | Adjustable slant boards; Weighted bars | Standardizes foot position; enables progressive overload in intervention studies [32] | Controls for foot orientation; allows quantification of stretch intensity |

| HNHA | HNHA, CAS:926908-04-5, MF:C17H21NO2S, MW:303.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dnca | Dnca, MF:C45H82N4O4, MW:743.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Methodological Selection in Clinical Research Context

The choice of dorsiflexion assessment method should align with research objectives and patient population characteristics. For large-scale screening or field-based studies, the tape measure method offers an optimal balance of reliability, cost-effectiveness, and practicality [33] [34]. When highest precision is required for biomechanical analysis, digital inclinometers provide superior metrological properties [34]. Smartphone applications represent a viable alternative when budget constraints preclude specialized equipment, though with slightly reduced reliability [35].

In post-surgical ankle fracture research, the functional nature of weight-bearing measurements is particularly relevant. These assessments demonstrate stronger correlation with gait parameters than non-weight-bearing measurements, capturing the integrated neuromuscular control required for daily activities [34] [31]. The persistent dorsiflexion limitations observed in ankle fracture patients [11] [17] underscore the importance of selecting sensitive measurement techniques capable of detecting clinically meaningful change throughout the rehabilitation continuum.

Diagram 2: Decision pathway for dorsiflexion assessment method selection. This algorithm guides researchers in selecting appropriate measurement techniques based on study objectives, population characteristics, and available resources.

The comparative analysis of weight-bearing dorsiflexion measurement techniques reveals distinct advantages and applications for each method. The Weight-Bearing Lunge Test with tape measurement emerges as the most reliable and practical option for clinical research, particularly in studies involving post-surgical ankle fracture patients where functional assessment is paramount. Inclinometer-based methods offer excellent reliability for precise angular measurement, while smartphone applications provide an accessible alternative with moderate reliability. The selection of appropriate assessment methodology is crucial for generating valid, reproducible data on dorsiflexion recovery in ankle fracture populations, ultimately contributing to enhanced rehabilitation strategies and improved functional outcomes.

Integrating Surface EMG with Computerized Dynamic Posturography for Neuromuscular Analysis

The objective quantification of neuromuscular control is essential for understanding postural stability in both clinical and research settings. The integration of surface electromyography (sEMG), which directly records muscle activation patterns, with computerized dynamic posturography (CDP), which quantifies balance performance through center of pressure (COP) movements, provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the neuromuscular basis of postural control [37]. This multimodal approach is particularly valuable in clinical populations, such as patients recovering from ankle fractures, where disrupted sensorimotor integration leads to significant balance impairments [38] [39]. While CDP output reflects the net result of balance control mechanisms, sEMG illuminates the specific muscular strategies employed to maintain stability [37]. This guide compares the performance of this integrated approach against using either methodology in isolation, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols for implementing this combined assessment strategy.

Comparative Framework: Integrated sEMG-CDP vs. Isolated Techniques

The following table summarizes the core capabilities of the integrated approach compared to the individual technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neuromuscular Assessment Techniques

| Assessment Feature | CDP Alone | sEMG Alone | Integrated sEMG-CDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balance Output Measure | Directly quantifies COP displacement, Limits of Stability (LOS) [40] [37] | No direct balance output | Directly quantifies COP displacement and LOS |

| Muscle Activation Timing | No muscle-specific data | Directly records onset, duration, and amplitude of muscle activity [38] [41] | Directly records muscle activation patterns |

| Neuromuscular Strategy | Inferred indirectly from COP data [37] | Identifies muscular coordination patterns [42] | Reveals direct relationship between muscle activation and balance output [37] |

| Sensory Integration Analysis | Excellent; can manipulate visual/somatosensory inputs [40] | Limited | Excellent; links sensory conditions to specific muscular responses |

| Clinical Application | Diagnoses balance deficit severity [40] | Identifies impaired muscle control [43] | Pinpoints whether deficit is strategic (muscle use) or mechanical (force output) [38] [37] |

| Data Correlation | Not applicable | Not applicable | Enables cross-correlation of EMG signals with COP trajectories (EMG-COP correlation) [37] |

Experimental Data from Integrated sEMG-CDP Studies

Key Findings in Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients

Integrated assessment reveals specific neuromuscular alterations in patients following bimalleolar ankle fracture surgery, which are not fully discernible through single-modality testing.

Table 2: Summary of Neuromuscular Findings in Ankle Fracture Patients via Integrated Assessment

| Study Parameter | 6 Months Post-Surgery | 12 Months Post-Surgery | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limb × Muscle Interaction | Significant interaction (F=30.806, p<0.001) in Y-Balance Test anterior direction [38] [39] | Differences diminish | sEMG + Y-Balance Test (Dynamic Balance) |

| Lateral Gastrocnemius Activation | Greater activation associated with limited dorsiflexion ROM [38] [39] | Trend toward normalization | sEMG + Y-Balance Test |

| Proximal (Hip) Muscle Recruitment | Increased reliance on hip strategy during dynamic balance [38] | -- | sEMG of gluteus medius during balance tasks |

| Dynamic Balance Performance | Significantly impaired [38] | Deficits persist, though improved | Y-Balance Test |

Key Findings in Other Neurological and Traumatic Conditions

- Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): During CDP reactive balance tests, adults with chronic severe TBI exhibit greater composite lower extremity EMG activity compared to matched controls, correlating significantly with poorer reactive balance performance. This indicates higher physiological effort is required to maintain balance even when independent ambulation is achieved [41].

- Post-Stroke Hemiplegia: Nonlinear network indices of sEMG (e.g., clustering coefficient, degree centrality) derived during standing reveal neuromuscular conditions in ankle-foot dysfunction that are not identified by traditional linear sEMG indices or CDP alone. These include altered inter-muscular coordination and reduced contribution of specific muscles like the medial gastrocnemius to the muscle network [42].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Integrated Assessment

Protocol 1: Static and Dynamic Balance with sEMG

This protocol is adapted from studies on ankle fractures and postural control [38] [37] [39].

1. Participant Preparation:

- sEMG Electrode Placement: Following SENIAM standards, place bipolar surface electrodes on key lower limb muscles. Essential muscles include: Tibialis Anterior (TA), Peroneus Longus (PL), Medial/Lateral Gastrocnemius (MG/LG), Soleus (SOL), Biceps Femoris (BF), and Gluteus Medius [38] [37]. Skin should be shaved, abraded, and cleaned with alcohol to achieve electrode-skin impedance below 6 kΩ [37].

- CDP Calibration: Calibrate the force plate according to manufacturer specifications (e.g., AMTI OR6 series, Bertec Balance Advantage) [40] [37].

2. Experimental Tasks:

- Static Balance: Participants perform bipedal standing on both stable and unstable surfaces for 30-80 seconds, looking straight ahead with hands on hips [37]. A minimum of three trials is recommended.

- Dynamic Balance: Participants perform the Y-Balance Test (YBT), reaching maximally in anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral directions while standing on a single leg [38] [39]. The Limits of Stability (LOS) test can also be used, where participants volitionally shift their COP toward visual targets [40].

3. Data Collection and Analysis:

- sEMG Data: Record raw signals at a minimum sampling rate of 1500 Hz. Process signals using band-pass filtering (e.g., 20-450 Hz), rectification, and smoothing. Calculate Root Mean Square (RMS) for amplitude and Median Frequency (MF) for spectral analysis [42]. For muscle synergy, compute nonlinear indices like Clustering Coefficient (C) and Degree Centrality (DC) [42].

- CDP Data: Record COP data at 1250 Hz. Calculate traditional sway parameters (path length, velocity, area) and LOS sub-measures: Reaction Time, Directional Control, Movement Velocity, Endpoint Excursion, and Maximum Excursion [40].

- Integrated Analysis: Use cross-correlation analysis to examine the temporal relationship between individual EMG signals and COP displacements in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions (EMG-COP correlation) [37].

Protocol 2: Reactive Balance with sEMG

This protocol is based on research with neurologically impaired populations like TBI [41].

1. Instrumentation:

- Use a computerized dynamic posturography system capable of delivering unexpected, multi-directional perturbations (e.g., PROPRIO 4000, Bertec Balance Advantage) [40] [41].

- Apply sEMG electrodes as described in Protocol 1 on muscles including Vastus Lateralis, Medial Hamstrings, Tibialis Anterior, and Medial Gastrocnemius [41].

2. Procedure:

- Participants stand on the platform, wearing a safety harness. The system delivers progressively increasing platform tilts (e.g., up to 14° at rates from 6°/s to 60°/s) for 120 seconds or until a balance loss criterion is met [41].

- Multiple trials (e.g., three) should be conducted with rest periods.

3. Data Analysis:

- Reactive Balance Score: Provided by the posturography system based on the magnitude of perturbation tolerated.

- EMG Analysis: Calculate composite EMG activity across all muscles for each epoch of the test. Correlate this composite activity with the overall reactive balance score [41].

Visualization of the Integrated Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data integration points for a combined sEMG-CDP assessment.

Integrated sEMG-CDP Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 3: Essential Materials for Integrated sEMG-CDP Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density sEMG System | Records myoelectric activity with high spatial resolution to study motor unit properties and muscle excitation [44]. | Systems with 2+ channels per muscle; Delsys Trigno, Noraxon TeleMyo [42] [37]. |

| Computerized Dynamic Posturography System | Precisely quantifies postural sway and reactive balance by measuring center of pressure (COP) [40] [41]. | Bertec Balance Advantage, Neurocom Smart Balance Master, PROPRIO 4000 [40] [41]. |

| Multiaxial Unstable Platform | Challenges the sensorimotor system to reveal compensatory neuromuscular strategies and deficits [37]. | MFT Challenge Disc, wobble boards [37]. |

| Disposable Surface Electrodes | Detects myoelectric signals at the skin surface. Pre-gelled Ag/AgCl electrodes ensure good signal quality. | Bipolar adhesive electrodes (e.g., Ambu Neuroline) with 20-25 mm inter-electrode distance [37]. |

| Skin Preparation Supplies | Reduces skin impedance to improve sEMG signal-to-noise ratio and reduce motion artifacts. | Abrasive gel, alcohol wipes, razors [42] [37]. |

| Signal Processing Software | Processes and analyzes raw sEMG and CDP data to extract relevant metrics and correlations. | MATLAB, Visual3D, custom scripts for nonlinear indices and cross-correlation analysis [42] [41]. |

| Dgts | Dgts, MF:C42H81NO7, MW:712.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dgdg | Dgdg, MF:C51H84O15, MW:937.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The integration of surface EMG and computerized dynamic posturography moves beyond singular-dimensional assessment to provide a powerful, multi-faceted tool for decoding neuromuscular control. As the comparative data demonstrates, this approach is uniquely capable of linking specific muscle activation patterns—such as the compensatory gastrocnemius activation in ankle fracture patients or the generalized co-contraction in TBI—directly to functional balance outcomes [38] [41]. For researchers conducting comparative analyses of gait and postural control, this methodology offers a more sensitive and informative framework. It not only identifies the presence of a deficit but also illuminates the underlying neuromuscular strategy, thereby guiding the development of more targeted and effective rehabilitation interventions.

Gait analysis is a critical tool for diagnosing mobility issues and monitoring rehabilitation, particularly after orthopedic events such as ankle fractures. Traditional laboratory-based systems, while accurate, are costly and impractical for widespread clinical use [45]. The emergence of smartphone-based gait analysis offers a promising alternative, providing a portable, cost-effective, and accessible means of quantifying gait parameters. This review objectively compares the performance of smartphone-based gait analysis technologies against established alternatives, framed within the critical context of rehabilitating post-surgery ankle fracture patients. We summarize validation data, detail experimental protocols, and provide visual workflows to guide researchers and clinicians in evaluating these novel tools.

Performance Comparison: Smartphone Gait Analysis vs. Alternative Modalities

The following tables synthesize quantitative data on the performance of various gait analysis technologies, with a specific focus on their application in post-surgery ankle fracture recovery.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Gait Analysis Technologies in Clinical Validation

| Technology | Key Measured Parameters | Validation against Gold Standard | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smartphone (Embedded IMU) | Stride time, step time, swing phase, double support [45] | Moderate to excellent validity for step/stride time (r=0.628-0.977); Poor-moderate for swing/double support [45] | High accessibility, cost-effective, enables mass screening & home monitoring [45] [46] | Lower validity for phase-specific parameters; Requires ~100 steps for reliable data [45] |

| Wearable IMU Systems (e.g., RunScribe, G-Sensor) | Gait speed, stride length, cadence, stance/swing phases [47] | High agreement for speed, length, cadence (ICC>0.90); More variability in stance/swing phases [47] | Reliable home-based monitoring; Provides rich, real-world data [47] | Requires multiple dedicated sensors; Potential for less natural gait with multiple attachments [45] |

| Computer Vision (e.g., iGait) | Spatiotemporal gait parameters from video [48] | Successful deployment in clinical rehab; Low fail rates (<10%) in capturing data [48] | Passive, markerless assessment; Scalable from mono- to multi-camera setups [48] | Emerging technology; Validation metrics and clinical interpretation still developing [48] |

| 3D Motion Capture (VICON) | Comprehensive kinematic data, gait events [45] | Considered the laboratory "gold standard" [45] | High accuracy and reliability for detailed biomechanical analysis [45] | Cost-prohibitive, non-portable, requires specialized lab and operators [45] |

Table 2: Gait Parameter Deficits in Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients vs. Healthy Individuals

| Gait Parameter | Post-Surgery Ankle Fracture Patients vs. Healthy Controls | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Walking Speed | Significantly slower (WMD = -0.13 m/s, P < 0.001) [11] [17] [49] | Indicator of overall mobility impairment and functional decline [46] |

| Step Length | Significantly shorter (WMD = -0.15 m, P < 0.001) [11] [17] [49] | Suggests reduced confidence or propulsive force on the injured side [46] |

| Single Support Time | Significantly reduced on injured limb (WMD = -16.59%, P < 0.001) [11] [17] [49] | Reflects pain, instability, or weakness during weight-bearing [17] |

| Cadence | Significantly lower (WMD = -8.44 steps/min, P < 0.001) [11] [17] [49] | Compensatory strategy to improve stability by slowing the gait cycle [17] |

| Peak Dorsiflexion Velocity | Significantly lower (WMD = -7.93 °/s, P = 0.005) [11] [17] | Indicates restricted and altered ankle joint kinematics and push-off [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Smartphone IMU Validation Protocol

A 2025 study established the validity and reliability of a smartphone-based gait assessment application [45].

- Participants: 26 healthy young adults.

- Sensor Placement: A Samsung Galaxy S22 smartphone was fixed horizontally on the waist at the L4-L5 level using a semi-elastic belt.

- Data Collection: Participants walked at a comfortable pace on a 10-meter pathway. Gait data were simultaneously captured by the smartphone's built-in IMU (accelerometer and gyroscope) and a 16-camera VICON motion capture system, with synchronization via a Bluetooth signal.

- Data Processing: Heel strike and toe-off events were detected from the smartphone's sensor signals using a peak detection algorithm. Temporal parameters (stride time, step time, swing phase, double support) were calculated and compared between the two systems.

- Analysis: Concurrent validity was assessed using Pearson's Correlation, and test-retest reliability was examined with Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) across two sessions scheduled 1-4 weeks apart [45].

Smartphone-Based Recovery Prediction Protocol

A 2025 study assessed the use of pre-injury smartphone data to predict mobility recovery after lower-extremity fracture [46].

- Study Design: Retrospective cohort study of 107 patients with surgically treated pelvic or lower-extremity fractures.

- Data Extraction: Consenting patients exported historical mobility metrics collected passively by their Apple iPhones via the Apple Health app. Data included step count, walking speed, step length, walking asymmetry, and double-support time from up to a year before the injury.

- Data Analysis: Pre-injury mobility baselines were established from data from the 6 months preceding the injury. Post-fracture outcomes were parameterized weekly. Nonlinear models were used to predict post-injury mobility, adjusting for age, sex, fracture location, and other covariates [46].

Multi-Pathology Gait Dataset Protocol

A 2025 study created a large, open-access dataset to support the development of gait analysis algorithms [50].

- Participants: 260 individuals, including healthy controls and patients with neurological or orthopedic conditions.

- Sensor System: Participants were equipped with four synchronized IMUs placed on the head, lower back (L4/L5), and the dorsal part of each foot.

- Protocol: A standardized test involved standing still, walking 10 meters, turning around, walking back, and stopping. This resulted in over 11 hours of gait time-series data, annotated with relevant clinical scores for each pathology [50].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Smartphone Gait Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process for conducting and validating smartphone-based gait analysis, from data collection to clinical application.

Ankle Fracture Recovery Pathway

This diagram outlines the pathological gait profile of ankle fracture patients and how smartphone data can model the recovery process, linking impaired parameters to their functional consequences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Tools for Smartphone Gait Analysis Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Smartphone with IMU | Samsung Galaxy S22 (LSM6DSO IMU) [45] / Apple iPhone (Health app) [46] | Primary data collection device; captures raw accelerometer and gyroscope signals during gait. |

| Gold-Standard Validation System | VICON Nexus 2 (16-camera system) [45] | Provides criterion measure for validating the accuracy of smartphone-derived gait parameters. |

| Dedicated IMU Sensors | XSens, Technoconcept I4 Motion, G-Sensor [50] [47] | Used as alternative wearable benchmarks or to create multi-sensor reference datasets. |

| Data Synchronization Tool | Arduino-produced analogue signal via Bluetooth [45] | Precisely synchronizes the start time of smartphone data collection with gold-standard systems. |

| Adhesive Straps & Belts | Manufacturer-designed straps, semi-elastic belt [45] [50] | Securely fixes sensors or smartphones to standardized body locations (e.g., waist, feet). |

| Algorithm & Software Packages | Peak detection algorithm [45], R packages (e.g., scam, splines) [46] | Processes raw sensor data to detect gait events and calculate spatiotemporal parameters. |

| Standardized Clinical Scores | Disease-specific clinical/radioclinical scores [50] | Provides essential clinical context and ground truth for correlating gait parameters with pathology severity. |

| (4R)-4-Decanol | (4R)-4-Decanol, CAS:138256-82-3, MF:C10H22O, MW:158.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PROTAC SMARCA2 degrader-3 | PROTAC SMARCA2 degrader-3, MF:C37H42N8O4, MW:662.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Rehabilitation Challenges and Protocol Optimization: Addressing Strength and Functional Asymmetries

Post-surgical immobilization and disuse trigger rapid and pronounced muscle atrophy and strength loss, presenting a significant clinical challenge in rehabilitation. Disuse atrophy (DA) particularly affects anti-gravitational muscles such as the quadriceps and calf muscles, with research indicating that spaceflight-induced DA results in approximately 15% muscle loss in quadriceps and gastrocnemius within just two weeks [51]. Similarly, 15 days of immobilization causes a significant decline in both volume (-2.8%) and thickness (-12.9%) of the medial gastrocnemius muscle [51]. This rapid deterioration of muscle tissue directly impairs functional capacity, as evidenced by studies of postoperative ankle fracture patients who exhibit significant impairments in gait parameters, muscle strength, and plantar pressure distribution compared to healthy individuals, often failing to regain pre-injury functional levels despite rehabilitation [11].

The relationship between muscle atrophy and strength deficits is particularly pronounced in peak torque production - the maximum torque output generated by a muscle group, which is crucial for functional movements. Middle-aged and older adults demonstrate notable declines in knee extensor peak torque, with studies revealing that knee extensor strength declines annually by 1.1-1.4% in adults aged 40-59 years [52]. This deterioration occurs even in the absence of significant changes in muscle mass, suggesting that neuromuscular factors substantially contribute to functional limitations [52]. In postoperative populations, these deficits become even more pronounced, creating a compelling clinical imperative for targeted strength training protocols specifically designed to overcome muscle atrophy and peak torque deficits.

Comparative Analysis of Functional Deficits in Post-Surgical Patients

Quantitative assessments of postoperative ankle fracture patients reveal persistent functional deficits despite surgical intervention and standard rehabilitation. A systematic review and meta-analysis comprising 12 studies and 219 patients demonstrated that postoperative ankle fracture patients exhibit significant impairments across multiple gait parameters compared to healthy controls [11]. These patients showed slower walking speed (WMD = -0.13, 95% CI [-0.45, -0.16], P < 0.001), reduced peak dorsiflexion angular velocity (WMD = -7.93, 95% CI [-13.45, -2.41], P = 0.005), and shorter mean step length (WMD = -0.15, 95% CI [-0.18, -0.12], P < 0.001) [11]. Single support time was also significantly reduced (WMD = -16.59, 95% CI [-19.18, -14.00], P < 0.001), along with significantly lower cadence (WMD = -8.44, 95% CI [-10.87, -6.01], P < 0.001) [11].