Advanced Design Methodologies for 3D Medical Equipment Simulations: Integrating AI, Additive Manufacturing, and Clinical Validation

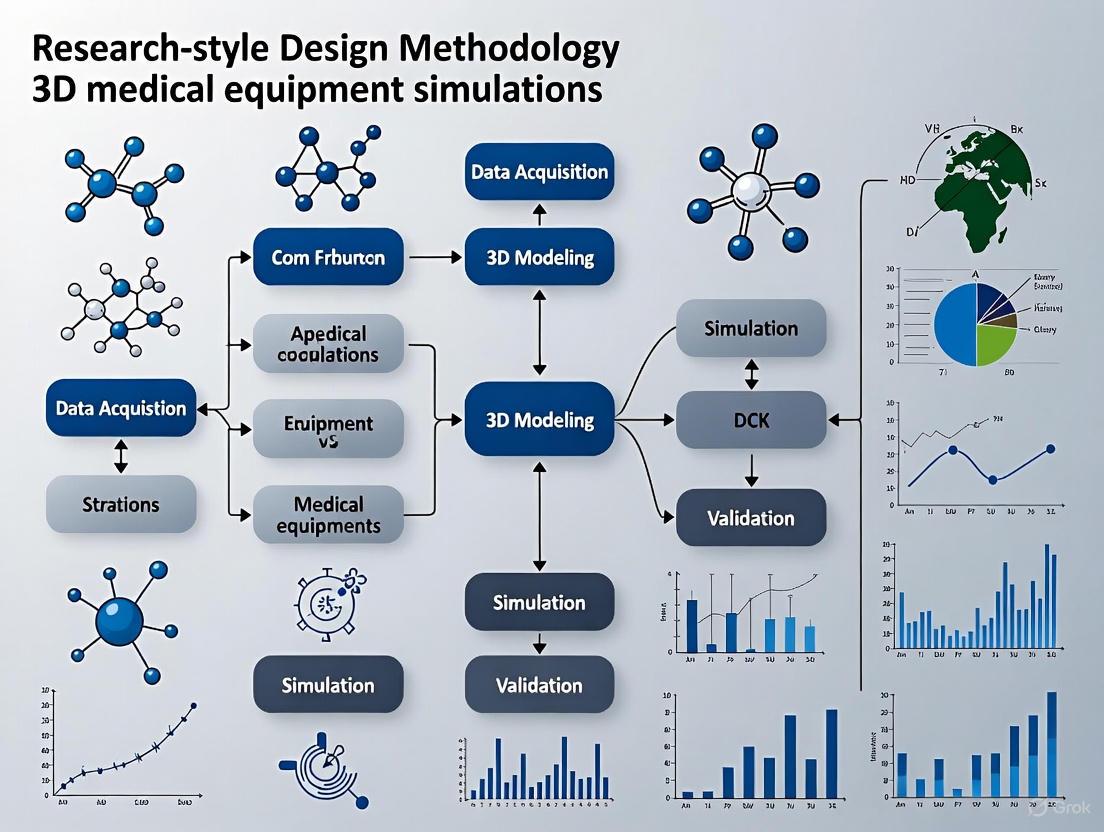

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the design methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations.

Advanced Design Methodologies for 3D Medical Equipment Simulations: Integrating AI, Additive Manufacturing, and Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the design methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations. It explores the foundational technologies of CAD, AI, and additive manufacturing that underpin modern simulation design. The piece details practical methodologies for creating and applying simulations across the medical device lifecycle, from prototyping to surgical planning. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for overcoming implementation barriers and concludes with robust validation frameworks and comparative analyses of leading technologies, offering a complete guide for integrating these tools into biomedical research and clinical practice.

The Core Technologies Powering Modern 3D Medical Simulation

The Role of Advanced CAD in Precision Medical Device Design

Computer-Aided Design (CAD) has evolved from a simple drafting replacement to a foundational technology in precision medical device development. In the context of design methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations research, advanced CAD systems provide the critical link between anatomical data and functional device prototypes. This technology enables the creation of detailed 3D digital twins of both human anatomy and proposed devices, allowing for exhaustive virtual testing and refinement before physical manufacturing begins [1]. For researchers and engineers, this represents a paradigm shift from traditional, iterative prototyping to a streamlined, simulation-driven workflow that significantly accelerates development cycles while enhancing patient safety and device efficacy.

The integration of CAD into medical device development addresses a fundamental challenge: the need to create highly complex, patient-specific devices that interact safely with human physiology. Modern CAD packages leverage increased processing power to provide flexible, powerful, and affordable product design capabilities to a widening user base [2]. Within a research framework focused on 3D medical equipment simulations, CAD serves as the primary platform for converting medical imaging data into actionable, manipulable models that can undergo simulated performance testing, design optimization, and manufacturing preparation.

CAD Applications Across Medical Specialties

Advanced CAD technology has demonstrated transformative potential across numerous medical specialties, enabling device personalization and surgical precision that was previously unattainable. The technology facilitates a seamless transition from diagnostic imaging to therapeutic intervention by converting standard medical scans into precise, patient-specific 3D models. This capability is particularly valuable in complex anatomical regions where standardized devices often provide suboptimal solutions [3].

The table below summarizes key applications of CAD across different medical specialties:

Table 1: CAD Applications in Medical Device Design and Treatment Planning

| Medical Field | CAD Application Examples | Key Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Orthopedics | Custom joint replacements, patient-specific surgical guides, spinal implants | Improved implant fit, reduced surgery time, enhanced biomechanical compatibility [3] |

| Cardiovascular Medicine | Personalized stents, heart valve repairs, surgical planning for congenital defects | Patient-specific design, reduced procedural risk, improved hemodynamic performance [3] |

| Dentistry | Dental implants, orthodontic devices, crown and bridge fabrication | Perfect fit, reduced adjustment needs, streamlined production [3] |

| Neurology | Custom cranial implants, surgical planning guides, brain mapping interfaces | Precision matching to anatomical defects, minimized brain manipulation [3] |

| Radiology | 3D model creation from DICOM data, image segmentation, diagnostic visualization | Enhanced diagnostic capability, improved surgical planning, better patient communication [3] [4] |

The transition from 2D imaging to 3D modeling represents a particular advancement in diagnostic and planning capabilities. As noted in research on 3D modeling in healthcare, physicians traditionally worked with "surrogates of anatomy" from CT and MRI scans, which presented 3D data sets within the limited scope of 2D interpretation [4]. CAD-enabled 3D modeling makes viewing anatomical images intuitive across all clinical specialties, leading to better diagnoses, surgical planning, and patient outcomes [4].

Quantitative Benefits of CAD Implementation

The integration of advanced CAD systems into medical device research and development yields measurable improvements across multiple performance metrics. These benefits extend beyond simple design efficiency to encompass clinical outcomes, cost management, and developmental timelines.

Table 2: Quantitative Benefits of CAD in Medical Device Development

| Performance Metric | Traditional Methods | CAD-Enabled Approach | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Accuracy | Manual measurements based on 2D scans | Voxel-accurate 3D models from CT/MRI data | Sub-millimeter precision in patient-specific devices [3] |

| Prototyping Time | Weeks for physical model creation | Hours/days for digital prototyping | Up to 80% reduction in initial prototype development [3] |

| Surgical Planning | Mental reconstruction of 3D anatomy from 2D images | Interactive 3D models with tissue differentiation | 32% better surgical outcome prediction in complex cases [4] |

| Device Customization | Limited modifications to standard designs | Full personalization based on patient anatomy | 100% patient-specific design capability [3] |

| Training Effectiveness | Theoretical learning, observation, cadavers | Interactive 3D simulation with haptic feedback | 85.1% skill proficiency vs. 62.1% with traditional methods [5] |

The quantitative advantages demonstrated in Table 2 highlight why CAD technology has become indispensable in modern medical device research. Beyond these metrics, CAD implementation generates significant qualitative benefits, including enhanced collaboration among multidisciplinary teams of engineers, clinicians, and researchers [3]. The ability to share and manipulate accurate 3D models across specialties fosters innovative problem-solving and ensures that all stakeholders contribute effectively to device optimization.

Experimental Protocols for CAD-Based Device Development

Protocol: Patient-Specific Implant Design Workflow

This protocol outlines a standardized methodology for developing patient-specific implants using advanced CAD tools, suitable for incorporation into research on 3D medical equipment simulations.

Objective: To create a functional, patient-matched implant from medical imaging data through a streamlined CAD workflow.

Materials and Equipment:

- DICOM data from CT/MRI scans

- Advanced CAD software with medical image segmentation capabilities

- High-performance computing workstation

- 3D printer for prototype validation (optional)

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Import

- Obtain DICOM format medical images from CT, MRI, or ultrasound scans

- Import DICOM data directly into CAD software using specialized medical modules

- Verify image resolution and slice thickness sufficient for intended application

Image Segmentation and Processing

- Apply threshold-based and region-growing algorithms to isolate target anatomy

- Manually refine automated segmentation to ensure anatomical accuracy

- Export segmented data as a 3D point cloud or surface mesh

3D Model Reconstruction

- Convert mesh data to solid or surface model compatible with CAD environment

- Apply smoothing algorithms to reduce stair-step artifacts from imaging data

- Verify dimensional accuracy against original scan measurements

Implant Design and Modeling

- Create implant geometry based on reconstructed anatomical model

- Incorporate design features addressing functional requirements (screw holes, porous surfaces)

- Apply design for manufacturing (DFM) principles to ensure producibility

Virtual Fit and Function Validation

- Perform interference detection between implant and anatomical models

- Conduct virtual surgical procedure to validate implantation approach

- Simulate biomechanical performance using integrated FEA tools

Design Finalization and Output

- Incorporate feedback from clinical partners on design modifications

- Prepare final CAD model for additive or subtractive manufacturing

- Generate comprehensive design documentation

Validation Metrics:

- Dimensional deviation <0.1mm from intended specifications

- Zero interference with critical anatomical structures

- Successful virtual implantation in simulated procedure

Protocol: Surgical Simulation and Planning Validation

Objective: To validate the efficacy of CAD-generated surgical plans through simulation-based testing, providing a methodology for evaluating surgical approaches and device performance before actual procedures.

Materials and Equipment:

- CAD models of patient anatomy and medical devices

- Surgical simulation software with haptic feedback capability

- Performance tracking system for metrics collection

- Control group data for comparative analysis

Procedure:

- Scenario Definition

- Define specific surgical scenario and critical steps

- Identify potential complications to be simulated

- Establish performance metrics and evaluation criteria

Virtual Environment Setup

- Import patient-specific CAD models into simulation environment

- Configure tissue properties based on anatomical characteristics

- Set up surgical tools and devices as interactive objects

Simulation Execution

- Conduct simulated procedure following planned surgical approach

- Introduce unexpected complications to test adaptability

- Record performance data and decision pathways

Performance Analysis

- Analyze quantitative metrics (procedure time, movement efficiency)

- Evaluate qualitative factors (decision quality, complication management)

- Compare outcomes against control data or established benchmarks

Plan Refinement

- Identify suboptimal aspects of surgical plan based on simulation results

- Modify approach to address identified challenges

- Iterate simulation until performance metrics meet targets

Validation Metrics:

- Reduction in simulated procedure time with successive iterations

- Improved efficiency of motion (path length, unnecessary movements)

- Enhanced complication management compared to baseline

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of advanced CAD methodologies in medical device research requires specific computational tools and software solutions. The table below details essential resources for establishing a capable research environment.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for CAD-Based Medical Device Development

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical CAD Platforms | Siemens NX, Dassault Systèmes SOLIDWORKS, Materialise Mimics | Anatomical modeling, device design, virtual prototyping | Direct DICOM import, specialized medical design features, simulation integration [1] |

| Simulation & Analysis | ANSYS, SimScale, Abaqus | Structural, fluid flow, and thermal analysis | FEA, CFD, integration with CAD data, specialized medical material libraries |

| Image Processing | 3D Slicer, ITK-Snap, Horos | Medical image segmentation, 3D reconstruction | DICOM processing, segmentation algorithms, 3D model export [4] |

| Collaboration Platforms | GrabCAD, Onshape, Siemens Teamcenter | Multi-disciplinary team collaboration | Cloud-based design sharing, version control, comment/review workflows [1] |

| Visualization & VR | Unity, Unreal Engine, SteamVR | Surgical simulation, device presentation | Real-time rendering, VR integration, haptic feedback support [5] |

The tools listed in Table 3 represent the core technological infrastructure needed for advanced CAD research in medical devices. When establishing a research environment, particular attention should be paid to software integration capabilities, as seamless data exchange between different systems is crucial for maintaining workflow efficiency [1]. Additionally, consideration should be given to computational hardware requirements, as complex simulations and large medical image datasets demand substantial processing power and memory resources.

Integration with Digital Twin Methodology

Advanced CAD serves as the foundation for creating comprehensive digital twins in medical device research—virtual replicas that mirror both the physical device and its interaction with human physiology. This approach enables researchers to conduct predictive analysis of device performance under various physiological conditions without risk to patients [1]. The digital twin methodology represents the cutting edge of simulation-based medical device research, providing a holistic framework for evaluating device function throughout its lifecycle.

The implementation of digital twins requires seamless integration between mechanical, electrical, and software components of medical devices. Siemens' comprehensive suite, for example, demonstrates how integrated tools can "expedite the development process and enhance functionality verification and hazard elimination" [1]. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for complex, connected medical devices that incorporate sensing, actuation, and data communication capabilities alongside their primary mechanical functions.

Challenges and Implementation Considerations

Despite its significant benefits, the implementation of advanced CAD systems in medical device research presents several challenges that must be addressed for successful integration:

- High Initial Costs: Acquisition of specialized medical CAD software and high-performance computing infrastructure represents substantial investment [3]

- Interoperability Issues: Integration with existing hospital information systems and research databases requires careful planning [3]

- Regulatory Compliance: Design processes must adhere to medical device regulations (FDA, ISO 13485), requiring rigorous documentation and validation protocols

- Data Security: Patient imaging and anatomical data must be protected in compliance with HIPAA and similar privacy regulations [3]

- Specialized Training Requirements: Researchers need training in both CAD methodologies and anatomical principles to effectively utilize these tools [3]

These challenges, while significant, can be mitigated through strategic planning, phased implementation, and collaboration with experienced partners in both clinical and engineering domains. The selection of appropriate software platforms with strong technical support and training resources is particularly important for research teams new to advanced CAD methodologies.

Advanced CAD technology has fundamentally transformed the methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations research, enabling a shift from physical prototyping to simulation-driven development. Through the creation of precise digital twins and patient-specific models, researchers can explore design alternatives, predict clinical performance, and optimize devices with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency. The structured protocols and tools outlined in this document provide a foundation for implementing these methodologies in research settings, with particular value for complex, patient-specific medical devices where traditional approaches fall short.

As CAD technology continues to evolve, its integration with artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and advanced simulation platforms will further enhance its capability to accelerate medical device innovation while ensuring patient safety and treatment efficacy. For research institutions and medical device companies, investment in these methodologies represents not merely a technological upgrade, but a fundamental advancement in the science of medical device development.

Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Data-Driven Simulation and Validation

Application Notes

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the simulation and validation of 3D medical equipment is revolutionizing design methodologies, enabling more rapid prototyping, enhanced performance prediction, and rigorous virtual validation. This paradigm shift is critical for developing next-generation medical robots, diagnostic devices, and surgical tools. The core of this approach lies in creating high-fidelity digital twins—virtual replicas of physical systems—that are informed by real-world data and can be used to train, test, and validate equipment in a safe, cost-effective simulated environment before physical prototyping [6].

Key advancements are being driven by platforms that leverage a three-computer system approach, which partitions the workload across specialized systems for AI training, physically accurate simulation, and real-time, runtime execution [6]. This architecture is foundational for managing the computational demands of complex simulations. Furthermore, national and municipal research initiatives are actively funding and promoting the development of AI-driven applications in smart healthcare, emphasizing intelligent surgical planning, medical robotics, and AI-assisted diagnostics [7] [8]. These initiatives highlight the critical role of synthetic data generation and hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing in overcoming the limitations of scarce clinical data and ensuring the reliability of AI models when deployed on physical hardware [6].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Targets in Recent AI-Driven Medical Equipment Research

| Research Focus Area | Key Performance Indicator | Target Value |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical Robotics (Sub-task Automation) | Procedure Automation | Precisely execute suturing, wound closure [6] |

| Robotic Ultrasound Imaging | Scan Automation | Autonomous probe positioning for image acquisition [6] |

| AI Chip Optimization for Medical Models | On-chip Memory Usage Reduction | Reduce storage footprint by >30% vs. 8-bit quantization [9] |

| Model Performance Retention | MMLU test score degradation ≤2% [9] | |

| Medical AI Model Inference | Concurrent Request Handling | Increase number of simultaneous requests by >30% [9] |

| Photonic Computing for Signal Processing | System End-to-end Latency | ≤1 millisecond [9] |

AI-Driven Simulation Platforms for Medical Robotics

The use of comprehensive AI-driven development platforms is becoming standard practice for medical robotics. For instance, the NVIDIA Isaac for Healthcare platform provides a domain-specific framework that integrates several core technologies [6]:

- NVIDIA Omniverse & Isaac Sim: Used to create high-fidelity, physics-enabled digital twins of surgical robots, instruments, and patient-specific anatomy. This allows for the safe simulation of complex procedures like suturing and tissue manipulation.

- Synthetic Data Generation: These simulated environments enable the massive generation of physically accurate synthetic data, which is crucial for training robust AI models without the need for extensive and difficult-to-acquire real-patient data.

- AI Model Training (Isaac Lab): The platform supports training robot control policies using reinforcement and imitation learning within the digital twin.

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Testing & Sim2Real Transfer: Trained AI models can be rigorously evaluated in the digital twin connected to real robot hardware (e.g., da Vinci Research Kit) before final deployment, ensuring a smooth transition from simulation to reality.

Early adopters like Moon Surgical and Virtual Incision are leveraging this pipeline for prototyping autonomous robotic systems and generating synthetic data to enhance surgical precision [6].

Data-Driven Validation and Regulatory Compliance

Validation is a critical component of the design methodology. AI-powered tools are emerging to streamline the verification and validation process, which is essential for regulatory compliance. Tools like MATLAB and Simulink provide environments for designing, simulating, and automatically generating code for patient monitoring algorithms and other medical device software [10]. These tools offer built-in testing and verification features that help meet stringent regulatory standards such as IEC 62304 (for medical device software) and support the generation of documentation required for FDA/CE compliance [10]. Key capabilities include:

- Requirements Traceability: Managing and linking design requirements to model components and tests.

- Model and Code Coverage Analysis: Quantifying the completeness of testing.

- Automated Code Generation: Producing optimized, reliable code for deployment, reducing manual coding errors.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Autonomous Surgical Sub-Task Validation

This protocol outlines the procedure for developing and validating an AI model for autonomous surgical sub-task execution, such as suturing, using a digital twin [6].

1. Objective: To train and validate a deep reinforcement learning agent to perform a defined surgical sub-task (e.g., suturing) within a simulated environment and successfully transfer the policy to a physical surgical robot.

2. Experimental Setup & Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Surgical Robot AI Validation

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Omniverse / Isaac Sim | Creates physics-enabled simulation environment for digital twin [6] | Platform for building 3D scenes with robotic arms, instruments, and anatomies. |

| da Vinci Research Kit (dVRK) | Provides an open-source hardware platform for physical validation [6] | Physical robotic system for deployment and testing. |

| Patient-Specific Anatomical Model | Serves as the simulation target for the surgical task [6] | 3D organ model (e.g., kidney, intestine) in USD format, derived from CT/MRI data. |

| Reinforcement Learning Framework (e.g., Isaac Lab) | Provides algorithms (e.g., ACT) for training robot control policies [6] | Trains AI agent through trial-and-error in simulation. |

| Stereo Camera / Endoscope Sensor Model | Provides visual perception input to the AI agent in simulation [6] | Simulated camera feed for depth and texture perception. |

3. Methodology: 1. Digital Twin Construction (Bring Your Own - BYO): - Import the CAD model of the surgical robot (e.g., dVRK) and instruments into NVIDIA Omniverse, converting them to USD format and defining joint properties and kinematics [6]. - Import or create a high-fidelity, patient-specific anatomical model using a defined workflow: start with synthetic AI-assisted CT synthesis (using a model like NVIDIA MAISI), followed by segmentation (using VISTA-3D), mesh conversion, cleaning, and texturing, resulting in a unified USD file [6]. - Configure the simulated sensors, such as a stereo endoscope camera, within the scene.

Protocol for AI Model Optimization on Dedicated Hardware

This protocol describes the methodology for optimizing a large medical AI model (e.g., for diagnostic imaging) to run efficiently on a specific dedicated AI chip, a process critical for deploying models in resource-constrained clinical settings [9].

1. Objective: To implement a mixed-precision quantization scheme for a large vision model on a specified AI chip (e.g.,燧原L600), reducing on-chip memory usage by over 30% while maintaining model accuracy (MMLU score drop ≤ 2%) [9].

2. Experimental Setup:

- Hardware: Target AI chip (e.g.,燧原L600).

- Software: High-performance mixed-precision inference system (e.g., MIXQ), deep learning framework (e.g., PyTorch).

- Models & Datasets: Target model (e.g., Qwen, DeepSeek series); benchmark dataset (e.g., MMLU for evaluation).

3. Methodology: 1. Model Structure Analysis: - Profile the computational graph of the target model to identify the minimal, independently quantizable sub-structures (e.g., attention blocks, feed-forward networks) [9].

Application Note: Computational Design of Patient-Specific Mandibular Implants

Workflow Integration and Performance Metrics

The integration of finite-element modelling (FEM), artificial neural networks (ANN), and Bayesian networks (BN) creates a cyber-physical loop for designing patient-specific mandibular reconstruction plates. This computational pipeline accelerates design convergence while providing formal risk metrics for clinical decision-making [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of the Integrated FEM-ANN-BN Workflow [11]

| Performance Parameter | Baseline Value | Optimized Workflow Value | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Finite-element modelling prediction accuracy | Not specified | 98% | Baseline |

| Artificial neural network surrogate fidelity | Not specified | 94% | Baseline |

| Maximum failure probability under worst-case loads | Not specified | <3% | Baseline |

| Titanium material usage | Solid-plate baseline | Reduced by 15% | 15% reduction |

| Development time | Solid-plate baseline | Shortened by 25% | 25% reduction |

| Multi-objective optimization efficiency | Solid-plate baseline | Raised by 20% | 20% improvement |

| Peak von Mises stress under 600N bite force | Not specified | 225 MPa | Within safety limits |

| Micromotion at bone-implant interface | Not specified | <150 µm | Promotes osseointegration |

Experimental Protocol: Digital Workflow for Mandibular Reconstruction

Protocol Title: Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow for Patient-Specific Mandibular Implant Design and Validation

Objective: To design, optimize, and fabricate a patient-specific titanium mandibular reconstruction plate with graded lattice architecture that meets biomechanical requirements while reducing development time and material usage.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-resolution helical CT scanner (0.6 mm slice pitch, 120 kV, 200 mA)

- Medical image processing software (Materialise Mimics Medical 24.0)

- Reverse engineering software (Materialise 3-matic Medical)

- Finite-element analysis software (ANSYS Mechanical 2024 R2)

- Machine learning framework (TensorFlow 2.15)

- Probabilistic programming library (PyMC 5.10)

- Direct metal laser sintering (DMLS) system (Concept Laser MLab)

- Medical-grade Ti-6Al-4V powder (Rematitan, particle size 15–45 µm)

- Vacuum heat treatment furnace

Procedure:

Medical Image Acquisition and Segmentation

- Acquire preoperative CT images of the patient's cranio-mandibular region using standardized protocols

- Import DICOM data into segmentation software and apply bone-threshold mask (>200 HU)

- Use automatic region-growing followed by manual editing to remove dental artefacts and floating bone islands

- Apply Laplacian smoothing kernel (λ = 0.5, five iterations) to generate watertight surface suitable for engineering

Anatomical Reconstruction and Implant Design

- Mirror intact contralateral hemimandible and blend across defect plane to establish target reconstruction contour

- Design fully integrated fixation plate (2.4 mm thickness) with screw apertures (2.5 mm diameter) at 8 mm pitch

- Loft plate seamlessly into buccal surface and apply 1 mm fillets to all sharp features to minimize stress concentrations

- Validate occlusal clearance and nerve-canal avoidance before exporting as STEP file

Finite-Element Model Development

- Construct high-fidelity finite-element model using quadratic tetrahedral elements (mean edge 0.8 mm in bone/plate, 0.4 mm in screws)

- Generate approximately 1.2 million elements to ensure computational accuracy

- Assign isotropic, linear-elastic properties (Ti-6Al-4V: E = 110 GPa, ν = 0.33; cortical bone: E = 13 GPa, ν = 0.30)

- Define frictionless contact for bone-implant interaction and bonded contacts for screw fixation

- Apply boundary conditions: fully constrain condylar heads and apply unilateral bite forces (300 N for average mastication, 600 N for maximum clench)

Surrogate Model Training and Validation

- Generate FEM database comprising 384 Latin-Hypercube variations in plate thickness, screw layout, and graded-lattice porosity

- Train fully connected ANN (64–32–16 hidden neurons, ReLU activation) on FEM results

- Validate surrogate using five-fold cross-validation to achieve mean absolute error below 6% and R² of 0.94

Uncertainty Quantification and Probabilistic Optimization

- Implement Bayesian network with No-U-Turn Sampler (5000 draws) to propagate input uncertainties

- Sample patient-to-patient variation in cortical-bone modulus (±20%), bite-force scatter (±30%), and build-porosity fluctuation (±5%)

- Apply genetic algorithm for multi-objective optimization with BN probabilistic constraints (failure probability <3%)

Additive Manufacturing and Post-Processing

- Prepare build data with 45° orientation relative to build plate to balance support volume with accuracy

- Generate hollow, self-detachable lattice supports on non-functional surfaces only

- Process medical-grade Ti-6Al-4V powder using DMLS parameters: layer thickness 25 µm, laser power 95 W, laser spot diameter 50 µm, scan speed 800 mm/s

- Perform post-processing vacuum heat treatment: ramp to 820°C over 4 hours, hold for 1.5 hours, cool under vacuum

Experimental Validation

- Fabricate fifteen candidate scaffolds for mechanical testing

- Validate FEM predictions against experimental measurements of stress and stiffness

- Verify that final selected design resists 600 N bite force with peak von Mises stress of 225 MPa and micromotion <150 µm

Figure 1: Computational-Experimental Workflow for Patient-Specific Mandibular Implants

Application Note: Biphasic Osteochondral Implants with Zonal Design

Workflow from MRI to Implantation

The fabrication of patient-specific, biphasic implants for osteochondral defect regeneration requires a specialized workflow from clinical MRI data to implantation. This approach addresses the complex zonal architecture of osteochondral tissue through advanced additive manufacturing techniques [12].

Table 2: Key Components in Biphasic Osteochondral Implant Fabrication [12]

| Component | Material System | Manufacturing Technique | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bony phase | Calcium phosphate bone cement | Extrusion-based 3D printing | Provides mechanical support and promotes bone regeneration |

| Cartilaginous phase | Hydrogel | Extrusion-based 3D printing | Mimics native cartilage extracellular matrix |

| Interface design | Zonal gradient architecture | Multi-material 3D printing | Recapitulates native osteochondral interface |

| Imaging source | Clinical MRI data | Patient-specific design | Ensures anatomical conformity |

| Design framework | Computer-aided design (CAD) | Digital workflow | Enables precise control over zonal architecture |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of Biphasic Osteochondral Implants

Protocol Title: Additive Manufacturing of Zonal Biphasic Implants for Osteochondral Defect Regeneration

Objective: To fabricate patient-specific, biphasic implants with zonal design for regeneration of osteochondral defects using clinical MRI data and extrusion-based 3D printing.

Materials and Equipment:

- Clinical MRI scanner

- Medical image processing software with CAD capabilities

- Extrusion-based 3D printing system with multi-material capability

- Calcium phosphate bone cement

- Hydrogel bioink (composition tailored to application)

- Sterile fabrication environment

Procedure:

Patient-Specific Data Acquisition

- Acquire high-resolution MRI data of the affected joint

- Segment osteochondral defect geometry using appropriate thresholding and region-growing algorithms

- Identify zonal boundaries between cartilage and subchondral bone regions

Biphasic Implant Design

- Create 3D model of the defect region using CAD software

- Design biphasic structure with bone-facing region and cartilage-facing region

- Incorporate zonal gradient at the interface to mimic native tissue transition

- Optimize pore architecture for each phase to facilitate tissue ingrowth

Material Preparation

- Prepare calcium phosphate bone cement according to manufacturer specifications

- Formulate hydrogel bioink with appropriate rheological properties for printing

- Sterilize all materials following established protocols for biomedical applications

Extrusion-Based 3D Printing

- Calibrate printing parameters for each material separately

- Program multi-material printing path based on the zonal design

- Fabricate implant using layer-by-layer deposition with precise material placement

- Maintain sterile conditions throughout the printing process

Post-Processing and Sterilization

- Crosslink hydrogel phase if required by material formulation

- Cure calcium phosphate phase according to established protocols

- Perform final sterilization using method compatible with both materials

- Package implants following regulatory requirements

Quality Control

- Verify dimensional accuracy against original CAD model

- Assess mechanical properties of each phase and the interface

- Confirm sterility through appropriate testing methods

Figure 2: Biphasic Osteochondral Implant Fabrication Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Additive Manufacturing of Medical Models and Implants [12] [11] [13]

| Material/Reagent | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical-grade Ti-6Al-4V | Titanium alloy with 6% aluminum, 4% vanadium | Provides high strength-to-weight ratio and excellent biocompatibility for load-bearing implants | Mandibular reconstruction plates, orthopedic implants [11] |

| Calcium phosphate bone cement | Ceramic-based material with composition similar to natural bone mineral | Serves as osteoconductive scaffold for bone regeneration | Bony phase of osteochondral implants, bone defect fillers [12] |

| Hydrogel bioink | Polymer network (e.g., gelatin methacrylate, polyethylene glycol) crosslinked in water | Mimics native extracellular matrix for cartilage tissue engineering | Cartilaginous phase of osteochondral implants, soft tissue models [12] |

| Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) | Transparent thermoplastic polymer | Provides optical clarity for educational models and temporary surgical guides | Dental surgical guides, anatomical training models [14] |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) | Biodegradable thermoplastic aliphatic polyester | Serves as low-cost material for anatomical models and surgical guides | Educational models, preoperative planning models [13] [14] |

| Polyetheretherketone (PEEK) | Semi-crystalline thermoplastic with excellent mechanical and chemical resistance | Provides radiolucency and mechanical properties similar to bone for implants | Patient-specific cranial implants, orthopedic applications [14] |

| Medical imaging contrast agents | Iodinated compounds or gadolinium-based agents | Enhances visibility of anatomical structures in medical imaging | Improves segmentation accuracy for patient-specific model design [11] |

| 10-Formyl-7,8-dihydrofolic acid | 10-Formyldihydrofolate|Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals | |

| Acetylshengmanol Arabinoside | Acetylshengmanol Arabinoside, CAS:402513-88-6, MF:C37H58O10, MW:662.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Note: Educational Implementation of 3D-Printed Patient-Specific Models

Validation in Dental Education

The implementation of patient-specific 3D-printed models in structured educational programs demonstrates significant benefits for clinical training. A study involving postgraduate periodontics and implantology students revealed high satisfaction with 3D-printed mandibular and maxillary models derived from Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) scans [14].

Table 4: Educational Outcomes from 3D-Printed Model Implementation in Dental Training [14]

| Educational Metric | Measurement Method | Results | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural comprehension improvement | 5-point Likert scale | Mean score: 8.38 ± 0.82 | Significant enhancement in understanding surgical procedures |

| Technical skill acquisition | Student self-assessment | Vast majority reported improvements | Better preparation for live patient procedures |

| Confidence in clinical application | Pre/post training assessment | Increased confidence levels | Reduced anxiety during transition to patient care |

| Educational Impact factor | Exploratory Factor Analysis | 53.09% of variance | Primary dimension of educational benefit |

| Technological Adoption factor | Exploratory Factor Analysis | 12.02% of variance | Secondary dimension emphasizing technology acceptance |

| Cumulative variance explained | Factor Analysis | 65.11% | Strong validation of two-dimensional framework |

| Bridge between theory and practice | Qualitative feedback | Overwhelmingly positive | Effective translation of knowledge to clinical skills |

Experimental Protocol: Integration of 3D-Printed Models in Surgical Training Curriculum

Protocol Title: Implementation and Validation of Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Models in Postgraduate Dental Surgical Training

Objective: To integrate patient-specific 3D-printed anatomical models into structured surgical training curriculum and evaluate their educational impact on postgraduate students.

Materials and Equipment:

- Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) scanner

- 3D printing system (appropriate for anatomical model fabrication)

- Dental model materials (various polymers/composites)

- Validated perceptions questionnaire

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

Patient Data Selection and Model Fabrication

- Select representative CBCT scans from clinical cases

- Segment anatomical structures of interest (mandible/maxilla)

- Design 3D-printed models maintaining patient-specific anatomy

- Fabricate models using appropriate 3D printing technology and materials

Curriculum Integration

- Develop structured training program incorporating 3D-printed models

- Design hands-on surgical exercises using patient-specific models

- Schedule training sessions within existing curriculum framework

- Prepare supporting educational materials

Participant Recruitment and Training

- Recruit postgraduate students in relevant specialties (periodontics, implantology)

- Conduct training sessions using 3D-printed models

- Provide supervised practice of surgical techniques

- Facilitate feedback and discussion sessions

Data Collection

- Administer validated perceptions questionnaire post-training

- Collect quantitative data using Likert-scale items

- Gather qualitative feedback through structured questions

- Ensure anonymity and voluntary participation

Data Analysis

- Perform exploratory factor analysis to identify key dimensions

- Calculate reliability metrics (Cronbach's alpha) for questionnaire

- Analyze quantitative data for trends and significance

- Conduct thematic analysis of qualitative feedback

Curriculum Refinement

- Incorporate feedback into model design and training methodology

- Optimize balance between technological innovation and educational objectives

- Address identified limitations (e.g., tactile realism improvements)

- Plan for longitudinal assessment of clinical skill transfer

The integration of immersive technologies—Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), and the Metaverse—is fundamentally reshaping the methodology behind surgical training and planning. These platforms address critical limitations in traditional medical education by creating controlled, repeatable, and risk-free environments for skill acquisition. The core value proposition lies in their ability to enhance procedural accuracy, improve knowledge retention, and accelerate the development of clinical decision-making skills [15]. For researchers designing 3D medical equipment simulations, understanding this technological landscape is paramount. These are not merely visualization tools but represent a paradigm shift towards data-rich, interactive simulation environments that can provide quantitative feedback on user performance, thereby informing better design choices for future medical training systems [16] [17].

The metaverse, conceptualized as a convergence of VR, AR, and other digital assets, creates a persistent virtual space for user interaction. Its applicability to surgical education stems from four key characteristics: immersive virtuality, which provides high-fidelity 3D environments; openness and interoperability, allowing seamless integration across platforms; user-generated content, enabling the creation of tailored medical simulations; and the use of blockchain technology for secure certification of skills and outcomes [15]. This framework offers an unprecedented opportunity to develop standardized, yet highly customizable, simulation-based training modules that can be collaboratively used and assessed across global institutions.

Current Applications and Performance Metrics

Immersive technologies are being deployed across a spectrum of surgical disciplines, from orthopaedics to general surgery, with measurable impacts on educational and clinical outcomes. The applications can be broadly categorized into three domains: procedural skills training, preoperative planning, and intraoperative guidance.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Immersive Technology in Surgical Training

| Application Area | Key Metric | Reported Improvement | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR Procedural Training | Procedural Step Accuracy | 92% accuracy achieved by VR-trained learners [16] | Osso VR platform studies |

| Error Reduction | 67% fewer errors and instructor prompts [16] | Randomized studies on VR training | |

| Procedural Completion Time | 25% faster completion of procedures [16] | Comparison with traditional methods | |

| Procedural Competence Scores | Up to 300% higher scores than traditional methods [16] | Orthopedic surgical training | |

| AR-Based Surgical Training | Surgical Accuracy | 25-35% better performance [18] | Training at King Faisal Specialist Hospital |

| Error Rates | Reduced by nearly one-third [18] | Augmented reality training programs | |

| 3D Model-Based Education | Learning Skills & Knowledge | Higher scores in most randomized trials [19] | Systematic scoping review of 15 RCTs |

| Test-Taking Times | Generally favored the 3D model group [19] | Assessment of 1659 medical students |

In surgical training, VR platforms like Osso VR provide clinically accurate simulations for practicing procedures, offering immediate performance-based feedback. This multi-modal approach combines individual and collaborative learning, rapidly scaling onboarding for nursing and surgical staff [16]. For preoperative planning, 3D modeling and AR are transforming how surgeons prepare for complex operations. For instance, the Advanced Imaging and Modeling (AIM) program converts 2D CT and MRI scans into interactive 3D models, allowing for improved understanding of anatomy and pathology, such as visualizing how a tumor wraps around organs [4]. In intraoperative settings, AR systems overlay medical images directly onto the patient, providing surgical guidance. FDA-cleared devices like the xvision Spine System and Medivis's Surgical AR project 3D models into the surgeon's visual field, enhancing precision in procedures like spinal instrumentation and tumor resection [20] [21].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Validating the efficacy of immersive technologies within a design methodology framework requires rigorous, standardized experimental protocols. The following sections detail methodologies for two key types of validation studies: assessing skill acquisition and evaluating visualization workflows.

Protocol for VR Surgical Skill Acquisition Study

This protocol is designed to quantify the impact of VR simulation training on the development of surgical competency, providing a model for validating new 3D simulation equipment [15].

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a VR training module in improving procedural accuracy, reducing error rates, and decreasing time-to-competence for a specific surgical procedure (e.g., arthroscopic meniscectomy).

Materials and Reagents:

- VR Simulation Platform: A head-mounted display (e.g., Oculus Quest, HTC Vive) with the targeted surgical training software installed [15].

- Assessment Metrics Software: Integrated system for capturing performance data (e.g., time to completion, path length of instruments, number of errors).

- Control Group Materials: Traditional training assets (e.g., video tutorials, cadaveric specimens, or box trainers).

- Pre- and Post-Testing Tools: Written knowledge tests and global rating scales for technical skills (e.g., Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills - OSATS).

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment and Randomization:

- Recruit surgical trainees (e.g., residents) with minimal prior exposure to the target procedure.

- Randomly assign participants to an intervention group (VR training) or a control group (traditional training).

Baseline Assessment:

- All participants complete a pre-test, which includes a knowledge exam and a baseline skill assessment on a physical model or the VR simulator itself.

Intervention Phase:

- VR Group: Complete a structured, self-guided curriculum within the VR simulator. This involves repeated practice of the procedure until a pre-defined proficiency level is reached.

- Control Group: Undergo an equivalent duration of training using standard methods (e.g., video review and practice on a physical model).

Post-Training Assessment:

- All participants perform the procedure in a simulated environment (e.g., a high-fidelity physical model or a live animal tissue model).

- Blinded expert evaluators assess performance using validated metrics like procedural checklists and global rating scales.

Data Analysis:

- Compare post-test scores between groups for statistical significance using t-tests for continuous data (e.g., time, accuracy scores) and chi-square tests for categorical data (e.g., error rates).

- Analyze learning curves within the VR group based on simulator-generated metrics.

Protocol for AR Visualization Workflow (VR-Prep)

This protocol outlines the use of an open-source workflow, "VR-prep," for processing medical imaging data for enhanced AR visualization on consumer devices. This is critical for research into making 3D simulations more accessible and efficient [22].

Objective: To optimize and assess a pipeline for converting DICOM image series into 3D models suitable for AR visualization on smartphones and tablets, evaluating processing time and image quality.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: 3D Slicer (open-source), Fiji (ImageJ, open-source), Medical Imaging XR (MIXR) mobile application.

- Hardware: Standard workstation for image processing, smartphone or tablet (iOS/Android).

- Input Data: De-identified DICOM series from CT, MRI, or PET-CT scans.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Anonymize the DICOM data set as per institutional review board protocols.

VR-Prep Processing (Experimental Workflow):

- Load the DICOM series into Fiji.

- Execute the VR-prep macro, which performs:

- File Size Reduction: Reduces the number of frames and overall data volume.

- Isotropic Voxel Conversion: Ensures uniform voxel dimensions for optimal 3D rendering.

- Slope and Bit-Depth Adjustment: Standardizes intensity values for accurate display.

- Save the processed image stack using 3D Slicer.

Control Workflow:

- Upload the original, unprocessed DICOM series directly to the MIXR web portal.

Quantitative Metrics Collection:

- Record the file size (MB), number of frames, and time required for upload and QR-code generation for both the original and VR-prepped data sets.

- Record the download time of the 3D object onto the mobile device.

Qualitative Image Quality Assessment:

- Have independent, blinded clinical raters evaluate both the original and VR-prepped 3D models in the MIXR app.

- Use a 5-point Likert scale to rate parameters like Look-Up Table (LUT) representation, sharpness, signal-to-noise ratio, and confidence in use for diagnostics.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Immersive Technology Research

| Item | Function | Example Products / Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| VR Simulators | Provides immersive environments for procedural practice and skill assessment. | Osso VR [16], Surgical Theater [20] |

| AR Visualization Software | Converts 2D medical images into 3D models for overlay in the real world. | Medivis Surgical AR [20], 3D Slicer [22] |

| Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) | Hardware for delivering immersive VR/AR experiences. | Apple Vision Pro [20], Meta Quest, Microsoft HoloLens [20] |

| Open-Source Data Pipelines | Workflows for processing and optimizing medical data for XR. | VR-prep workflow (Fiji, 3D Slicer, MIXR) [22] |

| Performance Analytics Platforms | Captures and analyzes user performance data from simulations. | Osso Loop learning platform [16] |

Visualization of Workflows and System Architecture

The effective implementation of immersive technologies relies on coherent workflows and system architectures. The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical relationships and data flows in key processes.

The integration of VR, AR, and the metaverse into surgical training and planning represents a significant advancement in design methodology for 3D medical simulations. Evidence consistently demonstrates that these technologies enhance learning efficacy, procedural accuracy, and spatial understanding of complex anatomy [16] [18] [19]. The experimental protocols and workflows detailed herein provide a foundation for researchers to systematically validate new simulation tools and contribute to an evolving ecosystem.

Future development in this field will likely focus on overcoming existing challenges, which include high technological costs, the complexity of content development, data security concerns, and the need for seamless integration with clinical workflows like Electronic Health Records (EHR) [15] [17] [20]. The convergence of AI with spatial computing promises optimized procedures through intelligent overlays and advanced data analysis [20]. Furthermore, the FDA's establishment of a dedicated list for authorized AR/VR medical devices underscores the regulatory pathway maturation, encouraging continued innovation [21]. For researchers, the trajectory is clear: the next generation of 3D medical equipment simulations will be more immersive, interoperable, and intelligent, fundamentally transforming how surgical skills are acquired and refined.

Building and Deploying 3D Simulations: From Concept to Clinic

The integration of three-dimensional (3D) printing into medicine represents a paradigm shift from conventional mass production to personalized, additive manufacturing [23]. This technology fundamentally transforms two-dimensional (2D) radiological data into tangible, patient-specific anatomical models, thereby enhancing surgical planning, medical education, and clinical device simulation [24] [25]. Establishing a robust, repeatable digital workflow is critical for ensuring the accuracy and clinical validity of the resulting 3D printed parts, which is a cornerstone of effective design methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations research. This protocol details the end-to-end process, from data acquisition to a validated 3D printable model, providing a structured framework for researchers and developers.

The Digital Workflow Process

The journey from a medical scan to a 3D printed model is a multi-stage process that requires precision at every step. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, from patient imaging to the final application of the 3D printed model in a research or clinical setting.

Stepwise Protocol and Methodology

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Verification The process begins with the acquisition of high-quality medical imaging data. Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are the most common sources, providing the necessary cross-sectional data of the patient's anatomy [24] [26]. The Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) standard is used for all data transfers.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Imaging Parameters: For CT, use the highest practical spatial resolution and low slice thickness (preferably ≤1 mm) to maximize detail. For MRI, select sequences that optimize contrast between the tissue of interest and surrounding structures.

- Verification Check: Inspect the DICOM series for artifacts, motion blur, and sufficient coverage of the anatomical region of interest (ROI). Ensure the data is complete and that the imaging parameters are documented.

Step 2: Image Segmentation Segmentation is the most critical and time-consuming step, involving the isolation of the ROI from the background image data. This process defines which pixels constitute the anatomy to be printed.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Software Loading: Import the verified DICOM series into specialized segmentation software (e.g., 3D Slicer, Mimics, Vital Images) [24].

- Thresholding: For CT data, use Hounsfield unit thresholds to automatically differentiate between bone (high HUs) and soft tissue (low HUs).

- Manual Refinement: Employ manual painting, erasing, and region-growing tools to correct errors in the automatic segmentation, particularly in areas where tissues have similar radiodensity or signal intensity.

- Output: Generate a labeled mask of the ROI.

Step 3: 3D Model Reconstruction and Mesh Creation The segmented 2D mask is converted into a 3D surface model. This process generates a polygonal mesh, typically composed of triangles, which represents the outer surface of the anatomy.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Algorithm Selection: Apply a marching cubes or surface rendering algorithm within the software to create the initial 3D mesh from the segmented mask.

- File Generation: The initial mesh is often generated in a proprietary format before being exported to a standard polygonal mesh format.

Step 4: Model Optimization and Repair The raw 3D mesh is often not suitable for 3D printing and requires optimization to ensure it is "watertight" (a manifold surface without holes) and structurally sound [26].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Software Tools: Use mesh editing software (e.g., Meshmixer, 3-Matic, MeshLab).

- Watertight Check: Run an automated check for holes, non-manifold edges, and self-intersections. Repair any identified issues.

- Decimation: Reduce the triangle count of the mesh if it is overly complex and detailed beyond the capability of the 3D printer, preserving critical anatomical features.

- Smoothing: Apply smoothing algorithms to reduce the "stair-step" appearance from the segmentation process, but avoid over-smoothing which can erase anatomical detail.

Step 5: Export to 3D Printable File The optimized mesh is exported into a file format that is universally recognized by 3D printing software.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Format Selection: Export the model in the Standard Tessellation Language (STL) or OBJ file format [24].

- Scale Verification: Confirm that the exported model's scale and units (e.g., millimeters) are correct.

Step 6: Physical 3D Printing The STL file is imported into a slicer program, which converts the 3D model into a series of 2D layers (G-code) that instruct the 3D printer.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Technology Selection: Choose the appropriate 3D printing technology based on the application. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) is common for cost-effective anatomical models, while Stereolithography (SLA) or Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) offer higher resolution for complex structures [24] [23].

- Orientation and Supports: Orient the model on the build plate to minimize supports and maximize strength. Generate necessary support structures for overhanging features.

- Print Execution: Initiate the print using a material suitable for the intended use (e.g., biocompatible resin for surgical guides, flexible filament for vascular models).

Step 7: Post-Processing and Validation After printing, the model requires finishing and must be validated against the original imaging data to ensure anatomical accuracy.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Post-Processing: Remove support structures, sand, and (if necessary) paint the model to enhance anatomical features [26].

- Validation: The principal investigator or a qualified medical expert must compare the physical 3D model directly with the original source imaging to verify that it accurately represents the patient's anatomy [26]. This is a critical quality control step before use in simulation or research.

Essential Digital Tools and Research Reagents

The digital workflow relies on a suite of software tools, each fulfilling a specific function. The table below categorizes and describes these key "research reagents" for the digital phase of model creation.

Table 1: Key Software Tools for the Medical 3D Printing Digital Workflow

| Tool Category | Example Software | Primary Function in Workflow | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation & Modeling | 3D Slicer, Mimics, Vital Images, 3D Doctor [24] | Converts DICOM images into segmented masks and initial 3D meshes. | Core platform for extracting specific anatomical geometries from patient data for device simulation. |

| Mesh Editing & Repair | Meshmixer, MeshLab, Netfabb [26] | Optimizes and repairs mesh models; makes them watertight and printable. | Ensures model integrity and readiness for manufacturing, crucial for generating reliable physical prototypes. |

| Computer-Aided Design (CAD) | SOLIDWORKS, CATIA [27] | Creates or modifies geometric designs; used for adding custom features or surgical guides. | Allows for the design of patient-specific medical devices or simulation apparatus that interface with the anatomical model. |

| Simulation & Analysis | Finite Element Analysis (FEA), Electromagnetic Simulation [27] | Virtually tests device performance and safety under simulated conditions. | Enables in-silico testing of medical devices against the anatomical model, reducing physical prototyping needs. |

| Collaborative Platforms | Synergy3dMed, 3DEXPERIENCE [27] [25] | Manages workflow, enables real-time communication, and stores data securely. | Supports cross-disciplinary collaboration between radiologists, engineers, and researchers, streamlining the development process. |

Advanced Considerations for Research

Integration with Medical Device Design and Simulation

The digital model serves as the foundation for advanced research applications. It can be incorporated into a Virtual Twin of human anatomy to run sophisticated simulations, such as drop tests, stress analysis, or electromagnetic compatibility, before any physical part is manufactured [27]. This aligns directly with the rigorous simulation testing requirements for medical devices, which demand validation under defined operating conditions that mimic the human body [28]. The accurate anatomical models produced by this workflow provide a superior in-vitro testing environment compared to simple mechanical fixtures.

Protocol for Model Validation and Fidelity Assessment

A key tenet of scientific research is the verification of methods. For 3D printed anatomical models, this involves quantifying their fidelity to the source data.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Dimensional Analysis: Use coordinate measuring machines (CMM) or micro-CT scanning to measure critical dimensions on the 3D printed model. Compare these measurements to the same dimensions taken from the source DICOM images.

- Volume Comparison: Calculate the volume of the segmented ROI in the software and compare it to the volume of the physical model, measured via water displacement or from the printed model's sliced data.

- Landmark Distance Error: Identify specific anatomical landmarks in the source images and on the 3D printed model. The spatial distance between corresponding landmarks quantifies the geometric error of the entire workflow.

Addressing Workflow Challenges

Researchers must be aware of inherent challenges. Segmentation accuracy is a primary source of error and is highly dependent on image quality and operator skill [24]. Software and training costs can be prohibitive, and the limited range of biocompatible materials approved for 3D printing can constrain the development of implantable devices [23]. Furthermore, the regulatory landscape for 3D printed patient-specific devices and anatomical models is still evolving, requiring careful consideration in any research program aimed at clinical translation [29] [23].

Point-of-care (PoC) 3D printing is revolutionizing healthcare by enabling the just-in-time creation of patient-specific anatomic models, surgical instruments, and implants within the hospital environment [30]. This approach transforms patient care by moving manufacturing directly to the clinical setting, blurring traditional lines between healthcare provider and device manufacturer. The technology has expanded beyond cranio-maxillofacial and orthopedic applications into congenital heart disease and oncology, where patient-specific models improve surgical precision and patient outcomes [31]. By 2025, advancements in automation, AI integration, and operational efficiency are making personalized medicine more accessible and scalable than ever before [31].

The fundamental value proposition of in-hospital 3D printing labs lies in their ability to create patient-matched solutions that would be impossible or impractical with traditional manufacturing approaches. From anatomical models for surgical planning to custom surgical guides and implants, PoC manufacturing offers unprecedented flexibility for clinical teams [32] [33]. This guide provides comprehensive application notes and protocols for establishing and maintaining a robust PoC 3D printing facility, with specific consideration to design methodology for 3D medical equipment simulations research.

Laboratory Setup and Operational Framework

Centralized Laboratory Configuration

A centralized operational model for hospital-based 3D printing offers significant advantages over distributed departmental approaches. Centralization enables resource optimization, standardized quality control, and regulatory compliance [32]. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of spatial organization, workflow design, and technical integration.

Table 1: Facility Zoning Requirements for Point-of-Care 3D Printing Labs

| Zone | Primary Functions | Environmental Controls | Equipment Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Material Storage | Raw material inventory, bioink storage | Temperature control (4-8°C for bioinks), dry conditions | Material handling equipment, refrigeration units [34] |

| Digital Processing | Medical image segmentation, 3D modeling, simulation | Standard office environment | Workstations with medical image manipulation software [34] |

| Pre-processing & Buffer | Sterile preparation, material handling | HEPA-filtered airflow, UV-C sterilization capabilities | Biosafety cabinets, material preparation stations [34] |

| Printing Operations | Additive manufacturing processes | Temperature control (4-65°C for printbed, 4-250°C for printheads) [34] | 3D printers (FDM, SLA, Material Jetting, SLS) [32] |

| Post-processing | Support removal, cleaning, finishing | Ventilation for chemical fumes, safety equipment | UV curing stations, chemical baths, finishing tools [32] |

| Quality Control | Dimensional verification, mechanical testing, biological assessment | Controlled environment for measurement equipment | Coordinate measuring machines, mechanical testers, microscopes [34] |

The centralized laboratory model managed by Biomedical Engineering or Radiology departments allows for consolidated expertise and more efficient use of financial resources [32]. This structure supports higher equipment utilization rates and reduces total staff hours required for maintenance and processing on a per-print basis. The technical resources within these groups and strong clinical relationships with key departments facilitate successful implementation [32].

Technology Selection and Integration

Selecting appropriate 3D printing technologies requires matching technical capabilities to clinical applications. A multi-technology approach typically provides the greatest flexibility for addressing diverse clinical needs.

Table 2: 3D Printing Technology Comparison for Medical Applications

| Process | Materials | Clinical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Thermoplastic filament (PLA, ABS) | Prototypes, surgical guides, anatomical models | Ease of use, functional prints, inexpensive | Variable durability, anisotropic properties, limited resolution [32] |

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Photo-polymer liquid resin | Surgical guides, dental models, hearing aids | Superior accuracy, excellent surface finish, wide material properties | Significant post-processing, support placement considerations [32] [35] |

| Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) | Powdered polymers (Nylon, TPU) | Functional prototypes, custom instruments | Strong prints, no support structures needed | Environmental concerns, porous surface finish [32] |

| Material Jetting | Photo-polymers | Multi-material anatomical models, realistic simulations | Mixture of multiple materials, wide range of material properties | Expensive, significant post-processing [32] |

| Binder Jetting | Powdered materials | Anatomical models with color texture | Full-color capabilities, fast printing | Fragile prints, significant post-processing [32] [33] |

Institutional needs assessment should guide technology acquisition. A balanced approach targets clearly identified clinical use cases while maintaining flexibility for diverse applications [32]. For comprehensive support, traditional subtractive manufacturing equipment (CNC mills, lathes) can complement 3D printing capabilities, allowing selection of the optimal technology for each application [32].

Digital Workflow and Simulation Protocols

Medical Image to Printable Model

The transformation of medical imaging data into printable 3D models requires specialized software and meticulous segmentation protocols. The process begins with acquiring high-quality DICOM data from CT, MRI, or other medical imaging modalities, with scan parameters optimized for the intended application.

Segmentation Protocol:

- Data Import: Load DICOM images into specialized medical segmentation software (e.g., Materialise Mimics, 3D Slicer)

- Thresholding: Apply Hounsfield unit-based or signal intensity thresholds to isolate target tissues

- Region Growing: Use connectedness algorithms to select contiguous anatomical structures

- Manual Editing: Refine selections through slice-by-layer correction of automation errors

- Mesh Generation: Convert segmented masks to 3D surface models using marching cubes algorithm

- Model Cleanup: Repair mesh errors, reduce polygon count, and smooth surfaces

- Design Modification: Add orientation markers, labeling, or analytical features

The integration of AI-enabled segmentation tools significantly reduces processing time while improving accuracy and reproducibility [31]. These systems leverage deep learning algorithms trained on annotated medical image datasets to automatically identify and segment anatomical structures.

Printing Process Simulation

Simulation software plays a critical role in predicting and mitigating printing failures before physical manufacturing begins. These tools create virtual environments that mirror the physical behavior of the printer, material, and model during the printing process [36].

Simulation-Based Optimization Protocol:

- Model Preparation: Import STL file into simulation platform (e.g., Autodesk Netfabb, ANSYS Additive Suite)

- Material Parameterization: Input material-specific properties (thermal expansion coefficient, elastic modulus, viscosity)

- Process Parameter Definition: Set printing parameters (layer height, print speed, temperature settings)

- Thermal Analysis: Execute thermal simulation to predict temperature distribution and cooling behavior

- Stress Analysis: Calculate residual stress accumulation throughout the build process

- Distortion Prediction: Generate deformation maps showing anticipated geometric deviations

- Support Optimization: Identify critical areas requiring support structures and optimize placement

- Compensation Algorithm Application: Apply geometric compensation to counteract predicted distortion

- Iterative Refinement: Modify design and process parameters based on simulation results

Advanced simulation platforms incorporate machine learning algorithms trained on historical print data to improve prediction accuracy over time [36]. This approach is particularly valuable for metal additive manufacturing where deformation from thermal stress is common and costly, though increasingly applied to polymer-based processes for applications requiring tight tolerances [36].

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Medical 3D Printing Applications

| Material Category | Specific Formulations | Primary Applications | Key Properties | Sterilization Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photopolymers (SLA) | Biocompatible resins (Class I/II), Dental SG resin | Surgical guides, dental models, hearing aids | High resolution, smooth surface finish | Ethylene oxide, gamma radiation, autoclave (specific formulations) [35] |

| Thermoplastics (FDM) | PLA, ABS, PETG, Nylon, PEEK | Anatomical models, instrument prototypes, custom jigs | Mechanical strength, thermal stability | Varied by material; most tolerate ethylene oxide [32] |

| Powder Materials (SLS) | PA12, PA11, TPU | Functional prototypes, custom instruments, prosthetics | Excellent mechanical properties, chemical resistance | Ethylene oxide compatible [32] |

| Bioinks | Alginate, gelatin methacryloyl, silk fibroin, chitosan | Tissue engineering, disease modeling, drug testing | Cell compatibility, tunable mechanical properties | Aseptic processing required; limited sterilization options [34] |

Material selection must balance mechanical requirements, biological compatibility, and regulatory considerations. For patient-specific devices, biocompatibility and sterilization capability are paramount, requiring rigorous material qualification [34] [35]. Natural polymers like alginate and chitosan offer enhanced biocompatibility but may lack mechanical strength, while synthetic options like PEEK provide superior mechanical properties but require thorough biological validation [34].

Quality Management and Regulatory Compliance

Quality Management System Framework

Implementing a robust Quality Management System (QMS) is essential for ensuring consistent production of safe and effective 3D printed medical devices [31] [30]. The QMS should encompass all aspects of the production process from design input to final device validation.

Quality Management Protocol:

- Design Control Implementation: Establish and maintain design history files for all patient-matched devices

- Process Validation: Execute installation qualification, operational qualification, and performance qualification for all manufacturing equipment

- Material Control: Maintain certificates of analysis for all raw materials and establish supplier qualification programs

- Equipment Maintenance: Implement preventive maintenance schedules and calibration protocols for all critical equipment

- Personnel Training: Develop comprehensive training programs with competency assessment and documentation

- Document Control: Establish controlled documentation systems for standard operating procedures, specifications, and records

Hospitals are increasingly adopting robust QMS to standardize processes and ensure compliance with regulatory expectations [31]. Software solutions such as Materialise Mimics Flow help hospitals document their case processes and achieve greater efficiency in quality management [31].

Regulatory Compliance Strategy

The regulatory landscape for PoC 3D printing spans multiple FDA centers, including the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), and Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) [37] [30]. Understanding device classification is fundamental to developing an appropriate regulatory strategy.

Device Classification Framework:

- Class I Devices: Present minimal risk and are typically exempt from Premarket Notification (e.g., anatomical models for visual reference)

- Class II Devices: Require Premarket Notification through the 510(k) pathway (e.g., diagnostic use anatomic models, surgical guides)

- Class III Devices: Demand Premarket Approval with clinical trial evidence (e.g., life-supporting implants) [30]

Most PoC 3D printed devices fall into Class I or II categories, though classification depends on intended use and risk profile [30]. The FDA does not regulate the practice of medicine, allowing physicians to use 3D printed devices without regulatory submission when not marketed or sold [30]. However, institutions should maintain comprehensive documentation including design history files, process validation records, and quality management system certification [34].

Validation and Testing Protocols

Mechanical Testing Protocol

Comprehensive mechanical validation ensures 3D printed devices meet performance requirements for their intended clinical applications. Testing should simulate anticipated in-use conditions.

Tensile Testing Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Print standardized test specimens (Type V dog bone per ASTM D638) in orientations representing production parts

- Conditioning: Condition specimens at 23±2°C and 50±5% relative humidity for at least 40 hours before testing

- Equipment Setup: Calibrate universal testing machine and install appropriate load cell (typically 5-50 kN capacity)

- Testing Parameters: Set initial grip separation to 115 mm, crosshead speed to 5 mm/min, and pre-load to 0.1 N

- Data Collection: Record load and extension data at minimum 10 Hz frequency until specimen failure

- Analysis: Calculate ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, and elongation at break

- Statistical Analysis: Apply Weibull analysis to assess structural reliability and predict failure probability [38]

Compressive Strength Testing:

- Specimen Geometry: Prepare cylindrical specimens (12.7 mm diameter × 25.4 mm height) or cube specimens (10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm)

- Test Configuration: Apply compressive load at constant crosshead speed of 1.3 mm/min

- Data Collection: Record load and displacement until specimen failure or 80% strain

- Analysis: Calculate compressive strength and modulus from stress-strain relationship

Dimensional Verification Protocol

Ensuring geometric accuracy is critical for patient-specific devices, particularly those interfacing directly with anatomy.

Coordinate Measurement Machine (CMM) Protocol:

- Equipment Preparation: Qualify CMM probe using reference sphere and establish machine coordinate system

- Part Fixturing: Secure 3D printed part using non-deforming fixtures that avoid measurement obstruction

- Feature Alignment: Align part coordinate system to CAD model coordinate system using datum features

- Measurement Plan Execution: Automatically measure critical features according to predefined measurement plan

- Data Analysis: Compare measured points to nominal CAD geometry and calculate deviation metrics

- Reporting: Generate comprehensive report including color deviation maps and statistical analysis

For complex internal geometries not accessible via CMM, micro-computed tomography (μCT) provides a non-destructive alternative for comprehensive volumetric analysis.

Process Validation Using Statistical Methods

Statistical methods play a crucial role in qualifying 3D printing processes and optimizing parameters for medical applications [38].

Taguchi Methodology for Parameter Optimization: