Advances in Electrical Impedance Tomography: From Deep Learning Reconstruction to Clinical and Preclinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest methodological advancements in Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT), a non-invasive, radiation-free functional imaging technique.

Advances in Electrical Impedance Tomography: From Deep Learning Reconstruction to Clinical and Preclinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest methodological advancements in Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT), a non-invasive, radiation-free functional imaging technique. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of EIT and the complete electrode model. It delves into cutting-edge reconstruction algorithms, particularly deep learning-based methods, and their application across scales—from lung and brain monitoring in patients to intracellular imaging in drug discovery. The content further addresses critical challenges in hardware implementation and system optimization, and provides a framework for the functional validation and comparative analysis of different EIT approaches, synthesizing key insights to guide future research and clinical integration.

The Fundamentals of EIT: Principles, Models, and the Ill-Posed Inverse Problem

Core Physical Principles and the Complete Electrode Model

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a non-invasive, radiation-free medical imaging modality that generates real-time images by measuring the bioimpedance distribution within biological tissues [1]. It operates on the fundamental principle that different tissues possess distinct electrical conductivity and permittivity properties, which can be exploited to create cross-sectional images of the body [1]. This application note details the core physical principles underpinning EIT, with a specific focus on the Complete Electrode Model (CEM), which is essential for accurate image reconstruction. The content is framed within a broader research thesis on advancing EIT imaging methodologies for clinical and research applications, including potential use in drug development for monitoring physiological changes.

Core Physical Principles of EIT

Fundamentals of Bioimpedance

Bioimpedance is a measure of a biological tissue's opposition to the flow of electric current. Tissue impedance (Z) consists of two primary components: resistance (R), which dissipates energy as heat, and capacitance (C), which stores and releases energy [1].

- Resistance and Capacitance in Tissues: The resistance of an aqueous tissue solution behaves similarly under both direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) fields. In contrast, capacitance arises primarily from the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes. This bilayer blocks DC but, in an AC field, stores and releases energy, facilitating current flow in a frequency-dependent manner [1].

- Frequency-Dependent Behavior: In AC fields, the overall tissue impedance is determined by both resistance and capacitance. This relationship varies with frequency due to the influence of cellular and extracellular structures [1].

- At low frequencies, current flows primarily around cells (extracellularly) because the cell membrane acts as a capacitor blocking current.

- At high frequencies, the capacitive reactance of the cell membrane decreases, allowing current to penetrate and flow through the intracellular compartments [1].

- Cole-Cole Plots: The frequency-dependent impedance spectrum of biological tissues is often visualized using Cole-Cole plots, where resistance and reactance form a characteristic semicircular curve over a range of frequencies [1].

The Inverse Problem in EIT

EIT belongs to a class of mathematical challenges known as ill-posed inverse problems [1]. The process involves:

- Forward Problem: Predicting surface voltage measurements based on a known internal conductivity distribution and applied currents. This is a well-posed problem with a stable, unique solution.

- Inverse Problem: Estimating the internal conductivity distribution from a set of boundary voltage measurements. This is ill-posed because [1]:

- Small errors or noise in voltage measurements can lead to large instabilities in the reconstructed image.

- The number of independent measurements is finite, while the conductivity distribution to be estimated is a continuous function within the object, making the solution non-unique.

Table 1: Comparison of EIT with Other Imaging Modalities [1]

| Parameter | EIT | CT | MRI | Ultrasound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Electrical Impedance | X-rays | Radio Waves | High-Frequency Sound |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High | Low |

| Radiation Type | Non-ionizing | Ionizing | Non-ionizing | Non-ionizing |

| Portability | Portable | Non-portable | Non-portable | Portable |

| Spatial Resolution | Low | 50-200 μm | 25-100 μm | 50-500 μm |

| Temporal Resolution | 20-100 ms (can be as fast as 0.1 ms) | 83-135 ms | 20-50 ms | 1-20 ms |

The Complete Electrode Model (CEM)

Model Definition and Significance

The Complete Electrode Model (CEM) is a mathematical model that provides a more accurate representation of the physical reality at the electrode-skin interface compared to simpler models like the Gap Model or Shunt Model. It is considered the gold standard for forward modeling in EIT because it accounts for several critical, real-world phenomena that other models neglect. The CEM is essential for achieving quantitatively accurate image reconstructions, particularly in clinical settings.

Key Physical Phenomena Accounted for by the CEM

The CEM explicitly incorporates three major factors:

- Discrete Electrode Size and Shape: Real electrodes have finite size and specific geometry, which directly influences the current injection pattern and the measured voltage profile. The CEM models this, unlike simpler models that assume point electrodes.

- Contact Impedance: The interface between the electrode and the skin is not perfect. It is characterized by a thin layer of high impedance, known as the contact impedance or electrode-skin impedance. This layer arises from electrochemical effects and the skin's stratum corneum. The CEM includes this as a key parameter (

z_c), which can vary from electrode to electrode due to differences in skin preparation, pressure, and gel quality. - Shunting Effect: The highly conductive metal electrode causes a "shunting" effect, meaning the electric potential is constant across the entire surface of a single electrode. The CEM enforces this as a boundary condition.

Mathematical Formulation

The CEM consists of the following set of equations that govern the electric potential, u, within the domain Ω:

Governing Equation (Conservation of Charge):

∇ ⋅ (σ ∇u) = 0inΩThis states that in the absence of internal current sources, the divergence of the current density is zero.Boundary Conditions on the Electrodes (

e_l):- Current Injection:

∫_(e_l) σ (∂u / ∂n) dS = I_lThe integral of the current density over the electrode surface equals the total applied current for that electrode. - Shunting Effect and Contact Impedance:

u + z_l σ (∂u / ∂n) = U_lone_lThis equation couples the internal potential at the boundary to the measured voltageU_lon thel-th electrode, via the contact impedancez_l.

- Current Injection:

Boundary Conditions on the Skin (non-electrode areas):

σ (∂u / ∂n) = 0on∂Ω \ ∪ e_lThis states that no current flows into or out of the domain through the skin areas not covered by electrodes.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard EIT Data Acquisition Protocol

This protocol outlines the methodology for acquiring EIT data from a human subject, such as for thoracic or cerebral monitoring.

I. Materials and Setup

- EIT system with a capable signal generator and data acquisition unit.

- Set of 16 or 32 electrodes (typically Ag/AgCl).

- Electrode gel.

- Measuring tape and skin marker.

- Computer with EIT control and reconstruction software (e.g., EIDORS).

II. Pre-Acquisition Procedure

- Subject Preparation: Clean the skin area where electrodes will be placed (e.g., thoracic region at the 4th-5th intercostal space for lung imaging, or around the head for cerebral application) with alcohol swabs to reduce contact impedance [1] [2].

- Electrode Placement: Pre-gel the electrodes. Place them equidistantly around the cross-section of the target organ. For cerebral EIT, 16 electrodes are commonly arranged in a single plane around the head [2]. Secure the electrode strap to ensure consistent contact pressure.

- System Calibration: Power on the EIT system and initialize the software. Perform a system self-test and calibration according to the manufacturer's instructions to minimize instrumental errors.

III. Data Acquisition

- Reference Measurement: Acquire a reference data set. In time-difference EIT, this is a baseline measurement before a physiological change (e.g., start of ventilation). In multi-frequency absolute EIT, this step is part of the single measurement frame [1] [2].

- Application of Current: The system applies a small, safe alternating current (typically ≤5 mA) through a pair of drive electrodes [1].

- Voltage Measurement: Simultaneously, the system measures the resulting electrical potentials at all other passive electrode pairs. This process is repeated for multiple independent drive electrode pairs following a specific pattern (e.g., adjacent or opposite). A complete data set with 16 electrodes typically yields 208 voltage measurements [1].

- Frame Generation: Steps 2 and 3 are repeated rapidly. Modern EIT systems can achieve a frame rate of 10-50 frames per second, providing high temporal resolution for dynamic monitoring [1].

- Multi-Frequency Acquisition (for MFEIT/fdEIT): For multi-frequency EIT, repeat steps 2-4 across a range of frequencies (e.g., 21 kHz to 100 kHz) to capture the impedance spectrum of tissues [2].

IV. Post-Acquisition

- Store the raw voltage data securely.

- Remove electrodes and clean the subject's skin.

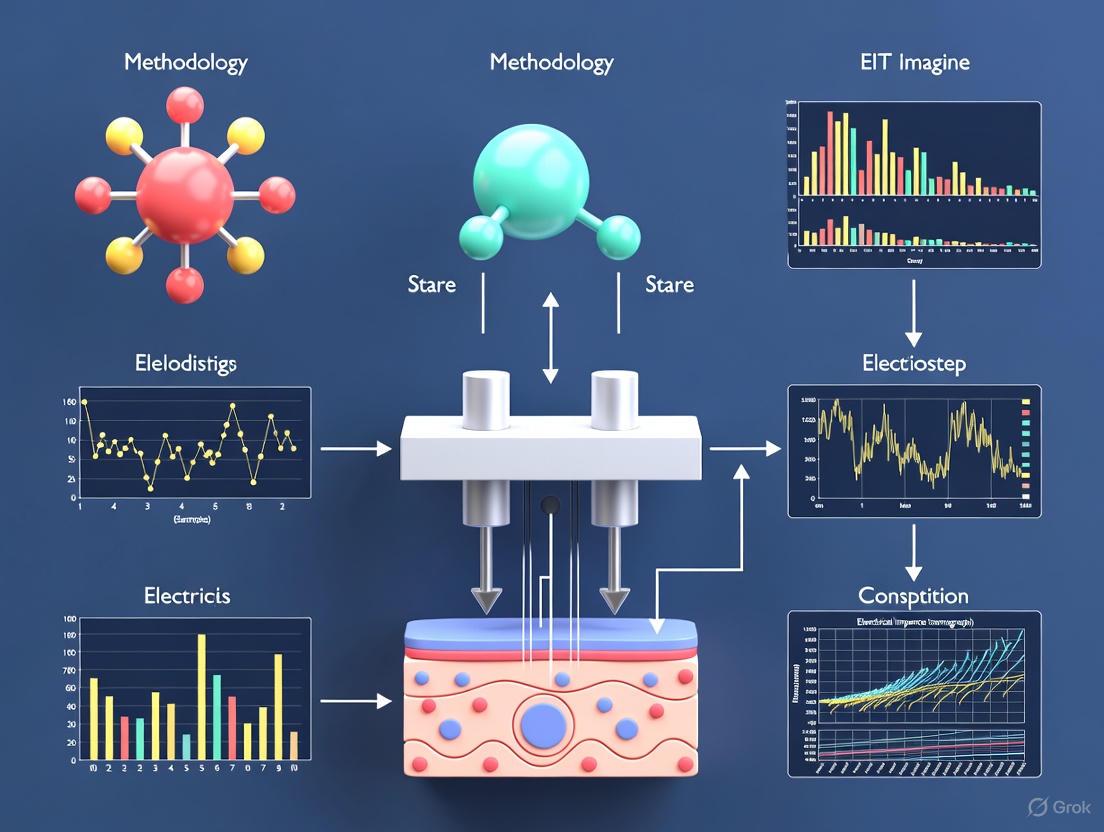

Diagram 1: EIT Data Acquisition and Image Reconstruction Workflow.

Protocol for Multifrequency EIT (MFEIT) in Cerebral Application

This specific protocol is adapted for the rapid detection of intracranial abnormalities, such as stroke or hemorrhage [2].

I. Subject Groups

- Healthy volunteers (control group).

- Patients with confirmed brain diseases (e.g., intracranial hemorrhage via CT/MRI).

II. MFEIT Data Acquisition

- Acquire cerebral MFEIT data at multiple frequencies (e.g., 9 frequencies in the 21 kHz - 100 kHz range) using an MFEIT system [2].

- Ensure consistent electrode placement for all subjects.

III. Image Reconstruction and Feature Extraction

- Reconstruct MFEIT image sequences using a frequency-difference (fdEIT) algorithm.

- For each image, define a Region of Interest (ROI). Extract the following quantitative indices [2]:

AR_ROI: The area ratio of the ROI.MVRRC_ROI: The mean value of the reconstructed resistivity change within the ROI.

- Calculate asymmetry indices to compare left and right hemispheres:

GAI(Geometric Asymmetry Index): Based onAR_ROI.IAI(Intensity Asymmetry Index): Based onMVRRC_ROI.

IV. Statistical Analysis

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., t-test) to compare the

GAIandIAIbetween the healthy volunteer group and the patient group. - A significantly higher asymmetry index in patients indicates a potential intracranial abnormality [2].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 2: Comparison of EIT Reconstruction Algorithms [1]

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Back-projection | Analytical, fast, low computational cost. | Simple, capable of real-time imaging. | Poor spatial resolution, prone to artifacts. |

| D-bar Method | Non-iterative direct method, improved stability. | Better robustness against noise. | Limited to certain domain types (e.g., 2D). |

| Regularized Newton-Raphson | Iterative, handles nonlinearity, requires regularization. | High accuracy, flexible. | Computationally intensive. |

| Machine Learning-Based | Data-driven, captures complex patterns (e.g., CNN). | Adaptive, potentially higher resolution. | Requires large training datasets; "black box" interpretability. |

Table 3: Standardized EIT Ventilation Indices for Pulmonary Monitoring [1]

| Term | Full Name | Explanation and Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| GI | Global Inhomogeneity | Measures uniformity of lung ventilation. A higher value indicates uneven distribution. |

| CoV | Center of Ventilation | Identifies the central position of airflow, helping assess ventilation distribution. |

| RVD | Regional Ventilation Delay | Indicates delays in ventilation across regions, suggesting airway obstruction. |

| EELI | End-Expiratory Lung Impedance | Reflects alveolar inflation and residual lung volume at the end of expiration. |

| TIV | Tidal Impedance Variation | Quantifies ventilation changes during each breathing cycle. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for EIT Research

| Item | Function and Description |

|---|---|

| Ag/AgCl Electrodes | Silver/Silver-Chloride electrodes are the standard for bioimpedance measurement due to their stable half-cell potential and low noise characteristics. |

| Electrode Gel (Conductive) | Hydrogel containing electrolytes (e.g., NaCl) to ensure good electrical contact between the electrode and the skin, reducing contact impedance. |

| EIT System with Active Electrodes | Modern systems integrate preamplifiers at the electrode-skin interface (active electrodes) to minimize cable-induced artifacts and improve signal fidelity [1]. |

| Multi-Frequency EIT System | A system capable of applying AC currents across a range of frequencies (e.g., 10 kHz - 1 MHz) to perform MFEIT/fdEIT and exploit tissue impedance spectra [2]. |

| EIDORS Software | An open-source software suite for EIT (Electrical Impedance Tomography and Diffuse Optical Tomography Reconstruction). It provides a rich environment for simulation, image reconstruction, and algorithm development. |

| Tank Phantoms | Physical models (often with saline) containing insulating or conducting inclusions, used to validate EIT systems and reconstruction algorithms before clinical use [2]. |

Diagram 2: Logical Relationships of the Complete Electrode Model (CEM).

Understanding the Severely Ill-Posed Nature of the EIT Inverse Problem

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a non-invasive imaging technique that reconstructs the internal electrical conductivity (and sometimes permittivity) distribution of an object by making electrical measurements on its surface [3] [4]. Its non-invasive nature, lack of ionizing radiation, and capability for real-time monitoring make it particularly attractive for medical applications such as lung and brain imaging, as well as for industrial process monitoring [3] [5].

Despite these advantages, EIT faces a fundamental mathematical challenge: the inverse problem of EIT is severely ill-posed in the sense of Hadamard [6] [7]. This means it lacks at least one of the three required properties for a well-posed problem: existence of a solution, uniqueness of the solution, and stability of the solution dependent on continuous data [7]. The EIT inverse problem is especially plagued by non-uniqueness and extreme sensitivity to noise and modeling errors, which leads to instability—small errors in measured data can cause large errors in the reconstructed image [6] [3]. This paper explores the nature of this ill-posedness, reviews contemporary solutions, and provides detailed protocols for addressing this central challenge in EIT research.

The Mathematical Foundation of EIT and Its Ill-Posedness

The Forward and Inverse Problem of EIT

The EIT forward problem is governed by the conductivity equation. Consider a bounded body domain ( \Omega ) with a conductivity distribution ( \sigma(x) > 0 ). The electrical potential ( u ) in the absence of internal current sources satisfies the elliptic partial differential equation:

[ \nabla \cdot (\sigma \nabla u) = 0 \quad \text{in} \ \Omega ]

Subject to appropriate boundary conditions, such as the Neumann condition ( \sigma \frac{\partial u}{\partial n} = j ) on ( \partial \Omega ), where ( j ) is the applied current density [6] [4]. The forward problem involves computing boundary voltages for a known conductivity and applied currents. The inverse problem—the central challenge of EIT—is to reconstruct ( \sigma ) from boundary measurements of current and voltage [7].

In practical applications, the relationship between measurements and the internal conductivity distribution is described by:

[ V = F(\sigma) + e ]

where ( V ) is the measured voltage, ( F(\cdot) ) is the nonlinear forward map, and ( e ) represents measurement noise [4].

Factors Contributing to Severe Ill-Posedness

The severe ill-posedness of the EIT inverse problem stems from several mathematical and physical realities [6]:

- The Smoothing Nature of the Forward Operator: The forward map ( F ) is a smoothing operator, meaning that high-frequency components of the internal conductivity are severely attenuated in the boundary measurements. Consequently, inverting this process amplifies high-frequency noise.

- Incomplete Boundary Data: In practical settings, only a finite number of measurements (typically from 8 to 128 electrodes) are available. This limited data fails to uniquely determine a continuous conductivity distribution.

- Nonlinearity: The mapping from conductivity to boundary measurements is inherently nonlinear, complicating the inversion process compared to linear problems.

Table 1: Fundamental Challenges of the EIT Inverse Problem

| Challenge | Mathematical Description | Practical Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Uniqueness | Different internal conductivity distributions can produce identical boundary measurements [7]. | Inability to distinguish between different tissue types or anomalies without prior information. |

| Instability | The inverse operator ( F^{-1} ) is discontinuous (unbounded); small measurement errors cause large reconstruction errors [6]. | High sensitivity to noise, requiring robust regularization methods for stable images. |

| Incomplete Data | Finite number of electrode measurements provide limited information about an infinite-dimensional parameter space [3]. | Low spatial resolution compared to modalities like CT or MRI. |

| Nonlinearity | The parameter-to-data map ( \mathcal{G}(u) ) is nonlinear [7]. | Requires iterative solutions or linearization approximations, increasing computational cost. |

Contemporary Approaches to Mitigating Ill-Posedness

Traditional Regularization and Algorithmic Families

Traditional approaches to managing EIT ill-posedness incorporate a priori information about the expected solution through regularization. These methods can be broadly categorized as follows [6] [4]:

- Variational Regularization Methods: These methods formulate the inverse problem as an optimization problem, minimizing a objective function that includes a data fidelity term and a regularization term. A classical example is the Tikhonov regularization, which incorporates a penalty on the ( L^2 ) norm (or other norms) of the solution or its derivatives.

- Iterative Reconstruction Algorithms: Examples include the Gauss-Newton method, which iteratively linearizes the problem and solves a regularized linear system at each step. These methods can achieve high accuracy but are computationally intensive and require careful choice of regularization parameters [6].

- Non-Iterative Direct Methods: Methods like the D-bar method and Calderón's method are based on theoretical breakthroughs involving Complex Geometrical Optics (CGO) solutions [6]. They are computationally efficient and avoid iterative forward problem solutions, but often produce images with lower resolution and are generally less accurate than iterative approaches [6].

The Rise of Learning-Enhanced and Hybrid Methods

Recently, deep learning and operator learning have emerged as powerful paradigms for solving inverse problems, offering alternatives to classical regularization [7] [4].

- End-to-End Inverse Operator Learning: This approach aims to directly learn the mapping from measured data ( y ) to the unknown parameters ( u ) using deep neural networks, effectively approximating the inverse operator [7]. These methods can leverage vast amounts of simulated or experimental data to implicitly learn prior information and regularization strategies.

- Hybrid "Learning-Enhanced" Methods: These approaches integrate deep learning with traditional algorithms to leverage the strengths of both. A prominent example is the Learning-Enhanced Variational Regularization via Calderón's method (LEVR-C) [6]. This method uses a deep neural network to extract a priori information about the shape and location (support) of the unknown conductivity contrast from an initial reconstruction provided by the computationally efficient Calderón's method. This learned information is then incorporated as a regularization term within a variational framework, which is subsequently solved by a Gauss-Newton method. This combines the speed of direct methods with the accuracy of iterative methods [6].

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Advanced Variants: PINNs embed the constraints of the governing differential equations into the loss function of a neural network [8]. For problems with extreme discontinuities, advanced frameworks like Information-Distilled PINNs (DR-PINNs) have been proposed. DR-PINNs combine reduced-order modeling, multi-level domain decomposition, and an ill-conditioning-suppression mechanism to handle singularities introduced by discontinuous loads or material properties [8].

Table 2: Comparison of EIT Reconstruction Algorithm Families

| Algorithm Family | Examples | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational/Iterative | Tikhonov, Total Variation, Gauss-Newton [6] | High accuracy with good regularizers; strong theoretical foundations. | Computationally expensive; sensitive to regularization parameter choice. |

| Direct/Non-Iterative | Calderón's method, D-bar method [6] | Computationally efficient; non-iterative, avoiding forward problem solving. | Lower resolution and accuracy; often limited to linearized approximations. |

| Deep Learning (End-to-End) | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Neural Operators [7] [4] | Fast inference; can learn powerful priors from data; grid-free. | "Black-box" nature; large, high-quality datasets required; generalization concerns. |

| Hybrid Learning | LEVR-C [6], Post-processing networks [4] | Combines efficiency and accuracy; incorporates physical models. | Increased complexity from multiple components. |

| Physics-Informed Learning | PINNs, DR-PINNs [8] | Respects underlying physics; does not require paired training data. | Can struggle with sharp discontinuities (standard PINNs); training can be challenging. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating EIT Ill-Posedness

Protocol 1: Implementing a Learning-Enhanced Variational Framework (LEVR-C)

This protocol outlines the methodology for combining Calderón's method with deep learning and variational regularization, as detailed in [6].

1. Objective: To reconstruct a high-contrast conductivity distribution ( \sigma(x) = 1 + m(x) ) by incorporating learned support information as a priori regularization.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for LEVR-C

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| EIT Measurement System | (e.g., ACT 5 system). Provides experimental boundary voltage data ( V ) from applied currents [9]. |

| Finite Element Software | (e.g., COMSOL, FEniCS). Used to solve the forward problem and generate training data. |

| Deep Learning Framework | (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow). For building and training the support-prediction network ( M_\Theta ). |

| Computational Atlas | An anatomical atlas of conductivity distributions, used for training or as a prior [9]. |

3. Methodology:

Step 1: Data Generation and Network Training for Support Learning

- Generate a large dataset of paired conductivity distributions ( {\sigmai} ) and their corresponding initial reconstructions ( {Ci} ) using Calderón's method.

- Train a deep neural network ( M_\Theta ) to map the initial Calderón reconstruction ( C ) to an approximate support mask ( D ) of the true contrast ( m ). The network learns to identify the likely shape and location of conductivity anomalies.

Step 2: Formulate the Learning-Enhanced Variational Problem

- Define the cost functional:

[

\min{m \in L^2(\Omega)} \|F(1+m) - V\|^2{\mathcal{Y}} + \alpha \|m\|^2{L^2(\Omega)} + \beta \|m - D\|^2{L^2(\Omega)}

]

where:

- ( F(1+m) - V ) is the data fidelity term.

- ( \|m\|^2 ) is the standard Tikhonov regularization for stability.

- ( \|m - D\|^2 ) is the learning-enhanced term, penalizing deviations from the learned support ( D ).

Step 3: Numerical Solution via Gauss-Newton Method

- Solve the above minimization problem using an iterative Gauss-Newton method. The learned support term ( D ) acts as a spatially varying prior, effectively guiding the solution towards physically plausible configurations.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated structure of the LEVR-C protocol:

Protocol 2: Anatomical Atlas-Driven Real-Time Reconstruction

This protocol describes the use of an anatomical atlas to provide strong prior information for reconstructing ventilation and pulsatile perfusion in preterm infants [9].

1. Objective: To achieve real-time EIT imaging with improved spatial resolution by incorporating an anatomical atlas into the reconstruction process.

2. Methodology:

Step 1: Atlas Construction

- Collect a database of anatomical images (e.g., CT scans) from a representative population (e.g., 89 infant scans).

- Segment the images into key tissues (soft tissue, lung, bone, etc.) and assign representative conductivity ( \sigma ) and susceptivity ( \omega\epsilon ) values at the operating frequency (e.g., 93 kHz).

- Compute the mean conductivity distribution ( \sigma_{\text{atlas}} ) across the registered datasets to create the prior atlas.

Step 2: The MEAN (MEan Atlas Noser-based) Algorithm

- Use the mean atlas conductivity ( \sigma_{\text{atlas}} ) as a non-constant initial estimate, rather than a homogeneous distribution.

- Compute the Jacobian (sensitivity) matrix around this prior estimate.

- Perform a single Newton-type step (e.g., similar to NOSER) to find the perturbation from the prior that best fits the measured data. This single-step approach enables real-time performance.

Step 3: Post-processing with Schur Complement

- To further enhance resolution, apply the Schur complement method as a post-processing step. This technique helps to sharpen organ boundaries and improve contrast in the reconstructed image.

The integration of a fixed atlas provides a powerful spatial prior, mitigating the non-uniqueness problem by constraining the solution to anatomically plausible configurations.

Visualization of the Core EIT Inverse Problem Challenge

The following diagram maps the fundamental information flow in the EIT inverse problem, highlighting the sources of ill-posedness and the points where regularization and prior information must be applied to achieve a stable, unique solution.

The severely ill-posed nature of the EIT inverse problem remains a central challenge that dictates the design and performance of all EIT imaging systems. While traditional regularization methods provide a mathematical framework for addressing instability and non-uniqueness, the emergence of deep learning and hybrid approaches marks a significant advancement. Techniques such as the LEVR-C method, which distill prior information from data, and anatomical atlas integration, which provides strong spatial constraints, demonstrate the power of combining computational intelligence with physical models. Furthermore, specialized frameworks like DR-PINNs show great promise for handling the extreme discontinuities that exacerbate ill-posedness. Future research will continue to blend these paradigms, moving toward more robust, high-resolution, and clinically reliable EIT imaging by directly confronting its foundational mathematical instability.

Application Notes

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a non-invasive, radiation-free imaging modality that reconstructs internal conductivity distributions by measuring boundary voltages. Its value lies in providing real-time, bedside functional imaging, particularly for dynamic physiological processes. Two domains where EIT demonstrates significant practical impact are clinical management of acute respiratory failure and experimental quantification of pulmonary edema in industrial research.

Medical Diagnostics: Multimodal Assessment of Post-Lung Transplantation ARDS

A 2025 clinical study demonstrates EIT's critical role in a multimodal framework for assessing ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch in patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) following lung transplantation [10]. The research highlights that EIT-derived parameters are more sensitive than quantitative CT for stratifying ARDS severity.

Key Quantitative Findings from Clinical EIT Application [10]

| Parameter | Description | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Inhomogeneity Index (GI) | Index of ventilation homogeneity; lower values indicate more homogeneous ventilation. | Higher in severe ARDS, indicating worsened ventilation distribution. |

| Center of Ventilation (COV) | Gravity-dependent distribution of ventilation. | Shifts with patient positioning and pathology. |

| Regional Ventilation Delay Index (RVDI) | Quantifies tidal ventilation delays, indicating obstructive pathology. | Significantly higher in low P/F group (severe ARDS). |

| EIT-Dead Space | EIT-derived fraction of unperfused ventilation. | Significantly higher in low P/F group; showed substantial agreement with ventilator-measured dead space. |

| EIT-V/Q Match | EIT-derived measure of regional ventilation and perfusion matching. | Significantly lower in low P/F group (P/F < 200 mmHg). |

| Ventilatory Ratio (VR) | Bedside estimate of physiological dead space. | Significantly higher in low P/F group; correlated positively with EIT-Dead Space. |

The study concluded that in lung transplant recipients with ARDS, the group with severe hypoxemia (P/F < 200 mmHg) showed significantly elevated VR, RVDI, and EIT-Dead Space, alongside reduced EIT-V/Q matching. Notably, quantitative CT-derived lesion volume parameters showed no significant difference between severity groups, underscoring EIT's superior sensitivity for functional assessment compared to static anatomical imaging [10].

Industrial Monitoring: Non-Invasive Quantification of Pulmonary Edema

In an industrial research context, EIT provides a non-invasive method for quantifying extravascular lung water (EVLW), a key metric in pharmaceutical development and toxicology studies for assessing drug-induced pulmonary toxicity or therapeutic efficacy. A seminal study developed a novel EIT-based metric, the lung water ratioEIT, which leverages gravity-dependent impedance changes during lateral body rotation to distinguish pulmonary edema from other thoracic fluids [11].

Key Quantitative Findings from Industrial EIT Application [11]

| Parameter/Metric | Description | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|

lung water ratioEIT |

Novel EIT parameter calculating ventilation redistribution during lateral body rotation. | Significantly correlated with postmortem gravimetric analysis (r=0.80, p<0.05), the experimental gold standard. |

| Experimental Model | Porcine model with two injury types: saline lavage (direct) and oleic acid (vascular). | Significantly changes after lung injury induction in both models. |

| Comparison Standard | Transcardiopulmonary Thermodilution (TCPTD). | Tracked changes in EVLW measured by TCPTD, a clinical monitoring tool. |

This EIT-based approach fulfills a critical need in industrial research for a non-invasive, bedside-capable, and reproducible tool to quantify pulmonary edema, eliminating the need for terminal procedures or invasive catheterization required by gold-standard methods [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: EIT for V/Q Mismatch in ARDS

This protocol outlines the methodology for using EIT in a multimodal assessment of ARDS, as described in the 2025 clinical study [10].

Workflow

The experimental workflow for assessing V/Q mismatch in ARDS patients using EIT and CT is visually summarized below.

Methodology

- Subject Enrollment: Recruit patients meeting the Berlin definition for ARDS, such as a cohort of post-lung transplant patients. Key inclusion criteria: P/F ratio ≤ 300 mmHg, mechanical ventilation with no spontaneous breathing effort, and both EIT monitoring and high-resolution CT performed within 24 hours of qualifying P/F measurement [10].

- EIT Data Acquisition:

- Place a 32-electrode EIT belt around the patient's thorax.

- Acquire EIT data for a minimum of 120 seconds under stable ventilator settings.

- For V/Q assessment, perform contrast-enhanced EIT using a bolus of hypertonic saline to calculate EIT-Dead Space and EIT-Shunt fractions [10].

- Multimodal Data Collection:

- CT Imaging: Perform high-resolution chest CT. Subsequently, process images using a computer-aided diagnostic model for semi-automated lung segmentation, lesion identification, and quantification of volumes (total lung, lesion, percentage lesion) [10].

- Gas Exchange & Respiratory Mechanics: Record arterial blood gases for P/F ratio calculation. Collect ventilator data to calculate the Ventilatory Ratio (VR) [10].

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- EIT Parameters: From the EIT data, calculate key parameters:

- Global Inhomogeneity Index (GI)

- Center of Ventilation (COV)

- Regional Ventilation Delay Index (RVDI)

- EIT-Dead Space and EIT-V/Q Match [10].

- Stratification: Divide subjects into groups based on P/F ratio (e.g., low P/F < 200 mmHg vs. high P/F 200-300 mmHg) [10].

- Statistical Analysis: Compare EIT parameters, CT metrics, and clinical parameters between the stratified groups to assess EIT's sensitivity and correlation with disease severity.

- EIT Parameters: From the EIT data, calculate key parameters:

Protocol 2: EIT for Quantifying Pulmonary Edema in Industrial Research

This protocol is adapted from the 2016 experimental study that validated the lung water ratioEIT against the gravimetric gold standard [11].

Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core operational principle of the lung water ratioEIT measurement based on lateral body rotation.

Methodology

- Experimental Setup:

- Subject Preparation: Anesthetize and instrument research subjects (e.g., porcine model). Place an EIT belt with 32 electrodes around the thorax. Secure the subject in a vacuum mattress to prevent electrode movement [11].

- Lung Injury Models: Randomize subjects into groups, including a sham group, a direct lung injury group (e.g., via saline lavage), and a vascular injury group (e.g., via oleic acid injection) [11].

- EIT Data Acquisition with Positional Changes:

- With the subject in a supine position, record baseline EIT data for at least 120 seconds.

- Rotate the subject to a 45° left lateral tilt. Allow 20 minutes for equilibration of fluid distribution, then record EIT data.

- Rotate the subject to a 45° right lateral tilt. After another 20-minute equilibration, record EIT data [11].

- Induce lung injury according to the experimental group assignment.

- Three hours post-injury, repeat the EIT data acquisition in all three body positions [11].

- Data Processing and

lung water ratioEITCalculation:- Process EIT datasets offline. For each body position, calculate the tidal variation (TV) of impedance for the left and right lungs.

- The

lung water ratioEITis calculated based on the differences in TV between the left and right lungs across the different tilts, which reflects the gravity-dependent redistribution of pulmonary edema [11].

- Validation against Gold Standard:

- Upon completion of the protocol, perform postmortem gravimetric analysis of the lungs to determine the actual EVLW content, which serves as the gold standard [11].

- Statistically correlate the

lung water ratioEITvalues with the gravimetrically obtained EVLW to validate the EIT method.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EIT Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| 32-Electrode EIT Belt & Data Acquisition System | Core hardware for applying safe alternating currents and measuring boundary voltage changes on the thorax. Essential for all EIT experiments [10] [11]. |

| Hypertonic Saline Bolus | Used as an intravenous contrast agent during EIT monitoring to enable the calculation of perfusion-related parameters and V/Q matching maps [10]. |

| Mechanical Ventilator | Provides standardized, controlled ventilation during EIT data acquisition, eliminating confounders from variable spontaneous breathing efforts [10] [11]. |

| Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Kits | For measuring PaO2 and FiO2 to calculate the P/F ratio, a key parameter for patient stratification and correlation with EIT findings [10]. |

| Quantitative CT Analysis Software | Enables semi-automated lung segmentation and quantification of high-density lesion volumes, providing anatomical context to complement EIT's functional data [10]. |

| Lung Injury Agents (e.g., Oleic Acid) | Used in industrial research settings to induce specific, reproducible models of vascular lung injury for validating EIT biomarkers like lung water ratioEIT [11]. |

The Complete Electrode Model as a Standard for Real-World Applications

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a non-invasive imaging modality that reconstructs the internal conductivity distribution of an object based on electrical measurements taken from surface electrodes [3]. Its appeal in medical and industrial settings stems from its non-invasive nature, real-time imaging capability, portability, and low cost compared to modalities like CT and MRI [3] [12]. The core challenge in EIT, however, lies in accurately modeling the galvanic interaction between the electrodes and the material under investigation, as this interaction significantly influences the generated electric field and, consequently, the reliability of the impedance analysis [13].

The Complete Electrode Model (CEM) has emerged as the state-of-the-art for addressing this challenge. It accounts for the crucial effects of electrode properties and their contact with the material, which are often overlooked in simpler models [13]. This document details the role of CEM as a standard in real-world EIT applications, providing a structured overview of its principles, a comparison with other models, quantitative tissue data, experimental protocols, and an exploration of advanced methodologies.

The Complete Electrode Model (CEM): Foundation and Formulation

The CEM's fundamental innovation is its realistic representation of the electrode-material interface. It explicitly models the electrochemical effects that occur at the boundary where the electrode meets the material (e.g., skin or tissue). The key physical phenomenon it captures is the shunting effect, where current preferentially travels through the highly conductive electrode itself, leading to a nearly constant electrical potential on the electrode surface [13].

The model incorporates two critical parameters:

- Contact Impedance ((z_c)): A simplified representation of the complex electrochemical interface, often modeled as a series impedance with the material [13].

- Electrode Potentials ((U_l)): The voltages measured on the electrodes, which are modeled as the sum of the voltage drops across both the material and the electrode impedance [13].

The mathematical formulation of the CEM consists of the following key equations that govern the electric potential, (u), within the domain (\Omega):

- Governing Equation:

∇ ⋅ (σ ∇u) = 0inΩ. This represents the conservation of charge in the interior of the domain [13]. - Boundary Conditions on Electrodes:

u + z_c σ (∂u/∂n) = U_lon each electrodee_l. This mixed condition couples the potential in the domain to the measured electrode voltage [13]. - Current Injection Condition:

∫_{e_l} σ (∂u/∂n) dS = I_lon each electrodee_l. This specifies the known injected current [13]. - Insulating Boundary Condition:

σ (∂u/∂n) = 0on the boundary not covered by electrodes. This ensures no current flows out except through the electrodes [13].

This comprehensive set of equations allows the CEM to minimize artifacts caused by inaccurate boundary modeling, providing a robust foundation for image reconstruction algorithms [13].

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Models

The following table contrasts the CEM with other common electrode models, highlighting its advantages for real-world applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Electrode Models in EIT

| Model Name | Key Assumptions | Limitations | Advantages of CEM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gap Model | Electrodes are point-like; contact impedance is infinite. | Highly inaccurate; fails to predict real-world measurements. | Accounts for finite electrode size and finite contact impedance. |

| Shunt Model | Electrodes are perfectly conducting; contact impedance is zero. | Neglects voltage drop at contact interface; less accurate. | Explicitly models the voltage drop across the contact layer. |

| Complete Electrode Model (CEM) | Finite electrode size; finite contact impedance ((z_c)). | Computationally more intensive. | Gold Standard: Most accurately represents physical electrode behavior; minimizes reconstruction artifacts [13]. |

EIT Applications and Tissue Properties

The effectiveness of EIT, and by extension the CEM, relies on the significant electrical property contrasts between different biological tissues and physiological states.

Table 2: Electrical Conductivity of Biological Tissues (at frequencies common in EIT) [3] [14]

| Tissue / Material | Conductivity (mS/m) | Clinical / Experimental Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) | 1450 - 2000 | Reference conductive medium; high conductivity impacts brain EIT [3] [14]. |

| Blood | 500 - 750 | Perfusion monitoring; detection of hemorrhage or ischemia [3] [14]. |

| Muscle | 200 - 450 | Direction-dependent conductivity (anisotropy); affects thoracic imaging [3]. |

| Gray Matter | 75 - 150 | Neural activity monitoring; stroke detection [14]. |

| Liver / Organs | 300 - 560 | Abdominal and cancerous tissue imaging [12]. |

| Fat | 20 - 50 | Poor conductor; provides contrast in thoracic and abdominal imaging [3]. |

| Lung (Inspired) | ~200 | Highly variable with air content; primary target for ventilation monitoring [3]. |

| Lung (Expired) | ~600 | Conductivity increases as air volume decreases [3]. |

| Bone (Cortical) | 6 - 20 | Highly resistive; acts as an electrical barrier in head and thoracic EIT [3] [14]. |

Key Application Areas

- Pulmonary Monitoring: EIT is extensively used for real-time, bedside monitoring of lung ventilation. It can identify sub-phenotypes of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) by clustering regional ventilation and perfusion data, guiding personalized PEEP therapy [15]. It also correlates with quantitative CT in assessing asthma, providing dynamic functional data [16].

- Hemorrhagic and Ischemic Stroke Detection: The significant conductivity difference between bleeding (high conductivity due to blood) and ischemic regions (low conductivity due to cytotoxic edema) makes EIT a promising tool for non-invasive cerebral monitoring [14].

- Hemolysis Monitoring: An EIT sensor with 16 electrodes can dynamically monitor blood hemolysis by detecting conductivity changes associated with the release of hemoglobin, offering a potential method for real-time, in-line blood quality control [17].

- Tactile Sensing: Flexible EIT sensors with lattice-structured conductive channels are used in robotics and electronic skin. Pressure deforms the channels, altering local conductivity and allowing reconstruction of touch location and force [18].

Experimental Protocol: CEM-Based Hemolysis Monitoring

The following protocol, adapted from Peng et al. (2025), outlines a specific application of EIT for real-time monitoring of hemolysis (the breakdown of red blood cells) using a CEM-based system [17].

Application: Real-time, in-line monitoring of dynamic hemolysis in stored blood samples or extracorporeal circulation. Principle: The release of hemoglobin and other intracellular components during red blood cell breakdown alters the electrical conductivity of the blood sample. The EIT sensor tracks these spatio-temporal conductivity changes.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for EIT-based Hemolysis Monitoring

| Item Name | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| EIT Sensor Array | 16-electrode circular PCB array (e.g., FR-4 substrate, copper electrodes). Configures the boundary for current injection and voltage measurement [17]. |

| Voltage-Controlled Current Source (VCCS) | Generates a high-frequency (e.g., 50-100 kHz), low-amplitude alternating current for safe and accurate tissue interrogation [12]. |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | High-precision unit for synchronously measuring boundary voltages from all electrode pairs. A key source of measurement noise if of low quality [17]. |

| Blood Sample | Whole blood, typically anticoagulated (e.g., with EDTA or Heparin). The sample under test [17]. |

| Hemolysis Inducer | Physical (e.g., ultrasound), chemical (e.g., saponin reagent), or material-based (e.g., copper wire) agent to simulate hemolysis [17]. |

| Reference Measurement System | Spectrophotometer for validating free hemoglobin concentration via optical density (OD) measurement at 545 nm [17]. |

Detailed Step-by-Step Workflow

Step 1: System Setup and Calibration

- Assemble the EIT system: Connect the 16-electrode sensor array to the DAQ hardware and the VCCS.

- Place the blood sample in the sensor's measurement chamber.

- Perform a system calibration by measuring a set of reference voltages ((V_{ref})) across all electrode pairs with a stable, non-hemolyzed blood sample or a calibration solution with known conductivity.

Step 2: Data Acquisition and Hemolysis Induction

- Initiate Baseline Monitoring: Acquire boundary voltage data for 60 seconds to establish a stable baseline.

- Induce Hemolysis: Introduce the hemolysis-inducing agent (e.g., insert a copper wire into the blood sample).

- Continuous Monitoring: Acquire boundary voltage data continuously throughout the hemolysis process and subsequent diffusion. A single data frame should include all voltage measurements from all combinations of drive and measurement electrodes.

Step 3: Data Pre-processing and Image Reconstruction

- Calculate Voltage Change: Compute the differential voltage set,

ΔV = V_touch - V_ref, for each time point. - Solve Inverse Problem: Input

ΔVinto the EIT image reconstruction algorithm (e.g., based on the CEM and a regularized Gauss-Newton method) to compute the change in conductivity distribution (Δσ) over time. - Generate 2D Images: Reconstruct a time-series of 2D conductivity distribution images visualizing the initiation and diffusion of the hemolysis process.

Step 4: Data Validation and Analysis

- Correlate with Gold Standard: Periodically sample the blood and measure free hemoglobin concentration using a spectrophotometer to obtain Optical Density (OD) values.

- Establish Correlation: Plot the EIT parameter (e.g., the sum of all voltage changes, (U_s)) against the OD values to create a calibration curve for quantifying hemolysis levels from EIT data alone.

Diagram 1: Hemolysis monitoring experiment workflow.

Advanced Methodologies and Future Directions

While the CEM is the current standard, research continues to advance the field of EIT. Two prominent areas of development are detailed below.

Beyond CEM: The Continuous Electrode Model

A recent innovation proposes a Continuous Electrode Model, which represents a significant generalization of the CEM. This method uses the same differential equation to model the entire measurement assembly—the electrodes, the material, and their interaction—using continuous functions [13].

Key Advantage: It allows for the calculation of the analytical solution's values at any point in the assembly without the discretization errors common in numerical methods like the Finite Element Method (FEM). This provides a more accurate and potentially more robust basis for EIT measurement modeling, especially for complex electrode geometries or material properties [13].

Deep Learning in EIT Reconstruction

The EIT inverse problem is severely ill-posed and non-linear. Deep learning (DL) has emerged as a powerful tool to address this.

- Approaches: DL methods for EIT include fully-learned networks (directly mapping voltage to conductivity), post-processing networks (refining images from traditional algorithms), and learned iterative methods (unrolling classical iterations with learned parameters) [19].

- Performance vs. Generalization: A 2025 review demonstrates that while fully-learned methods can outperform model-based approaches on data similar to their training set, they often face challenges in generalizing to out-of-distribution or real-world data. Hybrid methods, which incorporate physical models, strike a favorable balance between accuracy and adaptability [19].

The integration of precise models like the CEM or the Continuous Electrode Model into these learning frameworks is crucial for enhancing their physical plausibility and reliability.

Diagram 2: EIT inverse problem solution methods.

Next-Generation EIT Methodologies: Algorithms and Translational Applications from Bedside to Benchtop

Electrical Impedance Tomography (EIT) is a powerful, non-invasive imaging modality with critical applications in medical diagnostics, industrial process monitoring, and environmental studies. The core inverse problem of EIT—inferring the internal conductivity distribution of an object from boundary voltage measurements—is severely ill-posed [19] [20] [21]. This ill-posedness means the reconstruction is highly sensitive to noise and small errors in measurement data, making traditional computational approaches challenging.

The emergence of deep learning (DL) has driven significant progress in EIT image reconstruction. Deep learning methods can learn complex prior distributions directly from large datasets, offering greater flexibility than traditional hand-crafted priors [21]. These learned approaches have demonstrated potential to enhance reconstruction quality, increase computational speed, and improve robustness to noise. Current DL-based reconstruction methods can be broadly categorized into three paradigms: fully-learned, post-processing, and learned iterative methods [19] [21]. This article explores these revolutionary approaches, providing structured comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource information to equip researchers with practical tools for implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Methods in EIT

Table 1: Comparison of Deep Learning-Based EIT Reconstruction Methods

| Method Category | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully-Learned | Directly maps voltage measurements to conductivity images using a deep neural network [20]. | Fast reconstruction speed; eliminates iterative solving [20]. | Limited generalization to unseen data types; requires large, diverse datasets [19] [21]. | High accuracy on in-distribution data; outperforms model-based methods in simulated ellipse datasets [19]. |

| Post-Processing | Uses a DL network to enhance initial images from traditional algorithms (e.g., Calderón's method) [20] [6]. | Leverages strengths of classical methods; more stable than fully-learned approaches [6]. | Final image quality constrained by the initial reconstruction [6]. | Effectively improves resolution of initial guesses; successful support information extraction via Calderón's method [6] [22]. |

| Learned Iterative | Unfolds traditional iterative algorithms into network layers, learning parameters from data [21]. | Incorporates physical model; good balance of accuracy and adaptability [19]. | Complex training process; computationally intensive during training [21]. | Exhibits strong generalization on out-of-distribution and real-world data (e.g., KIT4 dataset) [19]. |

| Hybrid / LEVR-C | Combines learned support information from Calderón's method with variational regularization [6]. | Incorporates valuable prior knowledge; stable convergence [6]. | Performance depends on the accuracy of the learned support [6]. | Superior reconstruction performance and generalization ability in numerical experiments [6]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Overview from Experimental Studies

| Study / Dataset | Evaluation Metric | Model-Based Methods | Fully-Learned Methods | Hybrid Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Ellipses (In-Distribution) [19] | Reconstruction Accuracy | Lower accuracy | Highest accuracy | High accuracy |

| Out-of-Distribution Data [19] | Generalization Ability | Moderate performance | Significant performance drop | Best balance |

| KIT4 (Real Measurements) [19] [23] | Adaptability to Real Data | Lower spatial resolution | Challenges with measurement noise | Good accuracy and adaptability |

| Kuopio Challenge 2023 [23] | Segmented Image Quality (Level 1) | - | - | Score: ~0.74-0.98 |

| Kuopio Challenge 2023 [23] | Segmented Image Quality (Level 7) | - | - | Score: ~0.16-0.80 |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementation of a Fully-Learned Reconstruction Network

This protocol outlines the procedure for training a fully-learned deep neural network to solve the EIT inverse problem, directly mapping boundary measurements to conductivity images.

Data Preparation and Simulation

- Forward Model: Utilize the Complete Electrode Model (CEM) to accurately simulate real-world measurement conditions, including electrode modeling and contact impedance [21].

- Dataset Generation:

- Define a range of plausible conductivity distributions (e.g., inclusion shapes, sizes, and contrasts). For example, the Kuopio Tomography Challenge 2023 used a circular water tank with conductive and resistive inclusions of various shapes [23].

- Use the CEM to simulate boundary voltage measurements for each conductivity distribution.

- Add realistic noise to the simulated voltage data to improve model robustness.

- Data Split: Randomly partition the dataset into training, validation, and testing subsets (e.g., 70%/15%/15%).

Network Architecture and Training

- Architecture Selection: Employ a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with an encoder-decoder structure, or a fully-connected network for smaller problems.

- Loss Function: Use the Mean Squared Error (MSE) or Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) between the network output and the ground truth conductivity.

- Training Process:

- Optimize using the Adam optimizer.

- Implement early stopping based on validation loss to prevent overfitting.

- Validate reconstruction performance on the simulated test set.

Generalization Testing

- Out-of-Distribution Test: Evaluate the trained model on a test set with conductivity distributions that differ from the training data (e.g., different inclusion shapes) [19].

- Real Data Application: Finally, test the model on experimental datasets, such as the publicly available KIT4 or Kuopio Challenge 2023 data, to assess real-world performance [19] [23].

Protocol 2: Learned-Enhanced Variational Regularization via Calderón's Method (LEVR-C)

This protocol details a hybrid approach that combines the efficiency of a direct analytical method with the precision of a learned iterative scheme [6].

Initial Reconstruction Using Calderón's Method

- Compute an initial, low-resolution reconstruction of the conductivity contrast from the boundary measurements using the computationally efficient Calderón's method [6].

Learning the Support Information

- Network Training: Train a deep neural network to extract the approximate shape and location (support) of conductivity inclusions from the initial Calderón reconstruction.

- Input/Output: The network takes the initial Calderón image as input and outputs an estimate of the support region of the inclusions.

Variational Regularization with Learned Prior

- Formulate Optimization Problem:

- Define a cost function that includes a data fidelity term and a regularization term.

- Incorporate the learned support information as an explicit constraint or prior within the variational model.

- Solve the Inverse Problem:

- Use an iterative optimization algorithm, such as the Gauss-Newton method, to solve the regularized inverse problem.

- The learned support constraint guides the algorithm to produce a more accurate and stable final reconstruction.

- Formulate Optimization Problem:

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for EIT Research

| Category | Item / Resource | Specifications / Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Hardware | KIT4 EIT System [23] | A laboratory EIT system for acquiring real-world voltage data. | Data collection for algorithm validation. |

| Circular Water Tank with Electrodes [23] | A phantom setup with controlled inclusions (conductive/resistive plastics, metals). | Generating experimental training and test data. | |

| Ag/AgCl Electrodes [24] | Low-impedance electrodes for medical-grade EIT measurements. | Intracranial EIT monitoring in animal studies. | |

| Computational Models | Complete Electrode Model (CEM) [21] | A realistic mathematical model that accounts for electrode contact impedance. | Forward problem simulation for dataset generation. |

| Calderón's Method [6] [22] | A direct, non-iterative reconstruction method. | Providing initial guesses for hybrid/post-processing methods. | |

| Software & Data | Kuopio Tomography Challenge 2023 Dataset [23] | A publicly available dataset of real EIT measurements with ground truth. | Benchmarking and testing algorithm performance. |

| MATLAB / Python with EIT Toolboxes | Implementation platforms for EIT forward solvers and reconstruction algorithms. | Prototyping and deploying DL models. | |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow / PyTorch | Open-source libraries for building and training deep neural networks. | Implementing fully-learned, post-processing, and learned iterative networks. |

The integration of deep learning into EIT reconstruction represents a paradigm shift, moving from purely model-based approaches to data-driven methodologies. Fully-learned methods offer unparalleled speed for in-distribution data but face generalization challenges. Post-processing techniques provide a practical balance by enhancing existing algorithms. Learned iterative methods and other hybrid approaches like LEVR-C currently offer the most promising balance, embedding physical models within learned frameworks to achieve robust and accurate reconstructions, even on experimental data [19] [6].

Future research will likely focus on optimizing dataset construction to mitigate generalization issues, developing more efficient network architectures, and further refining the integration of physical models with deep learning. The ultimate goal is the creation of intelligent, integrated EIT diagnostic systems that leverage the full potential of these revolutionary reconstruction methods [20].

Clinical Significance of EIT in Critical Care

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT) has emerged as a transformative, non-invasive imaging modality for real-time monitoring of pulmonary function in both neonatal and adult critical care settings. This technology generates dynamic images of regional lung ventilation by measuring tissue bioimpedance, utilizing harmless alternating currents to reconstruct conductivity distributions that reflect tissue properties and air content [1]. The clinical significance of EIT stems from its unique combination of continuous bedside monitoring, absence of ionizing radiation, and high temporal resolution (20-100 milliseconds), enabling clinicians to visualize and quantify pulmonary dynamics not accessible through conventional imaging modalities [1] [25].

In neonatal critical care, EIT addresses a particularly urgent clinical need. The respiratory system of neonates exhibits unique physiological and anatomic attributes that increase vulnerability to respiratory distress and failure [5] [26]. Preterm infants face heightened risks from mechanical ventilation, including ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [26]. EIT offers a potential solution through precision monitoring that may reduce complications like pneumothorax, intraventricular hemorrhage, and BPD by guiding individualized lung-protective ventilation strategies [5]. The technology's capability for real-time assessment of pulmonary function enables clinicians to make informed interventions based on continuous data rather than intermittent snapshots [26].

For adult ICU patients, EIT provides crucial insights into managing complex respiratory conditions, particularly in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [25]. Its applications extend to optimizing positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP), assessing lung recruitment, detecting adverse events like pneumothoraces, and guiding weaning from mechanical ventilation [1] [25]. The recent publication of evidence-based recommendations with strong expert consensus (15 recommendations with >95% agreement) underscores EIT's evolving role in detecting dynamic pulmonary abnormalities that significantly influence clinical management and diagnosis [27].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of EIT Against Traditional Pulmonary Imaging Modalities

| Parameters | EIT | CT | MRI | Ultrasound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Impedance | X-rays | Radio waves | High frequency sound |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High | Low |

| Radiation Type | Non-ionizing | Ionizing | Non-ionizing | Non-ionizing |

| Portability | Portable | Non-portable | Non-portable | Portable |

| Spatial Resolution | Low | 50-200 μm | 25-100 μm | 50-500 μm |

| Temporal Resolution | 20-100 ms | 83-135 ms | 20-50 ms | 1-20 ms |

| Primary Limitations | Not mature yet, low spatial resolution | Ionizing radiation | Noisy, cost, low sensitivity | Operator dependency |

Technical Foundations and Physiological Principles

Fundamental Bioimpedance Principles

The physiological basis of EIT centers on the intrinsic electrical properties of biological tissues. Tissue impedance consists of both resistance and capacitance, with the aqueous components of tissue demonstrating similar resistance in both direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) fields, while the phospholipid bilayer of cell membranes creates capacitance that blocks DC but stores and releases energy in AC fields [1]. This frequency-dependent behavior underpins EIT's ability to discriminate between tissues: at low frequencies, electrical current is confined to extracellular spaces, whereas at higher frequencies, it penetrates cell membranes [1]. The complex relationship between resistance, capacitance, and frequency produces unique impedance spectra for different tissues, typically visualized as Cole-Cole plots, which form the basis for imaging contrast in EIT [1].

In pulmonary applications, EIT capitalizes on the significant impedance differences between air and fluid-filled spaces. Lung tissue resistivity correlates strongly with air volume, changing substantially between expiration (approximately 7 ohm-meters) and inspiration (approximately 24 ohm-meters) [26]. This variation occurs because air, being a poor electrical conductor, increases overall impedance as alveolar spaces expand and tissue layers thin during inspiration [26]. Conversely, increased lung fluid content (as in pulmonary edema) decreases impedance, providing a quantifiable marker of pathological processes [26].

EIT System Architecture and Operation

Modern EIT systems typically employ 16 electrodes arranged in a circular strap around the thorax, with most systems utilizing four active electrodes per measurement cycle [1]. A small alternating current (≤5 mA) is applied between one electrode pair while voltages are recorded from the remaining electrodes, generating approximately 208 measurements within 80 milliseconds [1]. This rapid data acquisition enables EIT to achieve 10-50 frames per second, providing the high temporal resolution essential for capturing ventilation and perfusion dynamics [1].

EIT operates in two primary modes: absolute imaging (reconstructing conductivity distribution at a fixed time) and time-differential imaging (imaging changes relative to a baseline) [1]. Clinical applications predominantly utilize time-differential imaging as it reduces instrument and contact errors, enhancing stability and reliability [1]. Reconstruction algorithms address the mathematically challenging "inverse problem" of estimating internal conductivity from boundary measurements, employing methods ranging from back-projection and sensitivity matrices to iterative techniques like variational or subspace-based optimization [1]. Recently, machine learning approaches including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and ensemble learning have shown promise in improving reconstruction accuracy and speed, though challenges remain in model interpretability and retraining requirements [1].

Table 2: EIT Reconstruction Algorithms: Comparative Analysis

| Method | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Back-projection | Analytical, fast, low computational cost | Simple, real-time capable | Poor spatial resolution, artifacts | GREIT algorithm |

| D-bar Method | Non-iterative direct method, improved stability | Better noise robustness | Limited to certain domains | 2D domain EIT |

| Regularized Newton-Raphson | Iterative, handles nonlinearity, requires regularization | High accuracy, flexible | Computationally intensive | Gauss-Newton with Tikhonov regularization |

| Machine Learning-Based | Data-driven, captures complex patterns | Adaptive, potentially higher resolution | Requires large training datasets | CNN-based impedance reconstruction |

Standardized Application Protocols

EIT Acquisition and Setup Protocol

Proper electrode placement is fundamental to obtaining reliable EIT data. For most pulmonary applications, the electrode belt should be positioned transversely between the 4th and 5th intercostal spaces, measured at the parasternal line [25]. Placement accuracy is critical - positioning too low introduces artifacts from diaphragmatic movement, while placement too high may underrepresent dorsal lung regions [25]. Belt rotation should be avoided as it distorts the reconstructed image, and a truly transverse orientation (not oblique) is essential for accurate dorsal ventilation assessment [25].

Belt size selection should follow manufacturer recommendations based on half-chest perimeter (measured from sternum to spine) to ensure optimal inter-electrode spacing and skin contact [25]. Electrode-skin contact can be enhanced using water, crystalloid fluids, ultrasound gel, or device-specific contact agents [25]. The system should include a signal quality check and calibration when possible, with recordings initiated after at least one minute of signal stability to ensure baseline reliability [25].

When clinical factors prevent ideal belt placement (e.g., chest tubes, wounds, or bandages), a higher placement is recommended over a lower one [25]. Most EIT systems can function properly with one or two non-functioning electrode pairs (for 16 and 32 electrode belts, respectively) [25]. For longitudinal measurements, marking the belt position with a skin marker enhances comparability between recording sessions [25].

Protocol for Controlled Mechanical Ventilation

EIT provides critical insights for managing mechanically ventilated patients, particularly in optimizing PEEP and preventing ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI). The following step-by-step protocol outlines the standardized approach:

Initial Setup: Position the EIT belt correctly and ensure stable signal acquisition. Record baseline ventilation for at least 5 minutes with current ventilator settings [25].

PEEP Titration Maneuver:

- Conduct a low-flow inflation maneuver or PEEP trial with incremental/decremental PEEP changes [25].

- Monitor end-expiratory lung impedance (EELI) changes to assess recruitment/derecruitment [1].

- Analyze global inhomogeneity (GI) index to identify PEEP levels that minimize ventilation heterogeneity [1].

- Calculate regional ventilation delay (RVD) to detect poorly ventilated areas [1].

Tidal Volume Distribution Assessment:

Recruitment Assessment:

Ongoing Monitoring:

Protocol for Spontaneous Breathing Trials

EIT enhances prediction of weaning outcomes during spontaneous breathing trials (SBT). The standardized protocol includes:

Pre-SBT Baseline: Record at least 10 minutes of stable EIT data during mechanical ventilation [1].

SBT Monitoring:

Failure Prediction Criteria:

Post-SBT Analysis: Compare pre- and post-SBT parameters to identify patients at risk of extubation failure [1].

Neonatal-Specific Application Protocol

Neonatal EIT application requires special considerations due to unique physiological characteristics:

Device Configuration: Use specially designed neonatal electrode belts with appropriate sizing for chest circumference [5] [26].

Monitoring Applications:

Data Interpretation Adjustments:

EIT Data Processing and Analysis Framework

Signal Processing Workflow

EIT signal processing involves sequential steps to extract clinically meaningful information from raw impedance data:

Filtering: Remove noise and artifacts while preserving respiratory and cardiovascular signals. Low-pass filters typically eliminate cardiovascular artifacts, but more sophisticated approaches (e.g., frequency-based separation) may be employed during offline processing [25]. Filtering should be applied to pixel impedance data before summation to avoid phase-related distortions [25].

Lung Segmentation: Identify functional lung regions within the EIT image. This process separates ventilation-related impedance changes from cardiac activity and other sources [25]. Multiple algorithms exist for automated lung segmentation, with consistency being crucial for longitudinal comparisons [25].

Region of Interest (ROI) Selection: Divide the lung into clinically relevant regions for quantitative analysis. The standard approach partitions the lung into four equal vertical regions (ROI1-ROI4 from ventral to dorsal) [1] [25]. Some applications may benefit from alternative segmentation strategies based on specific clinical questions.

Functional Parameter Calculation: Compute quantitative EIT indices including:

- Tidal Impedance Variation (TIV): Reflects tidal volume changes [1]

- End-Expiratory Lung Impedance (EELI): Tracks end-expiratory lung volume changes [1]

- Global Inhomogeneity (GI) Index: Quantifies ventilation distribution heterogeneity [1]

- Center of Ventilation (CoV): Identifies the central position of ventilation [1]

- Regional Ventilation Delay (RVD): Detects delayed ventilation in specific regions [1]

Technical Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Despite its clinical utility, EIT faces several technical challenges:

The Inverse Problem: Image reconstruction from surface measurements is mathematically ill-posed, resulting in limited spatial resolution and quantitative inaccuracy [1]. Modern reconstruction algorithms and machine learning approaches help mitigate these limitations [1].

Electrode Contact Variability: Skin-electrode impedance variations introduce artifacts [1]. Active electrode systems with integrated preamplifiers minimize these effects [1].

Limited Anatomical Coverage: Conventional EIT monitors a single transverse plane, excluding apical and basal regions [1]. Multiplane systems and rotating electrode belts are under development to address this constraint [1].

Sensitivity to Non-Ventilation Factors: Pleural effusions, pneumothoraces, and body position changes affect impedance measurements [25]. Recognizing characteristic patterns of these conditions enables their identification and, in some cases, quantitative assessment [25].

Diagram 1: Comprehensive EIT Data Acquisition and Processing Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from patient setup to clinical decision-making, mapping the five core EIT processes defined by the TREND consensus group [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Components for EIT Investigation

| Component Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| EIT Hardware Platforms | Commercial systems (Swisstom, Dräger); Open-source platforms [28] | Data acquisition and voltage measurement | Active electrode systems minimize artifacts; ASIC/SoC designs improve integration [1] |

| Electrode Arrays | 16-32 electrode belts; Neonatal-specific belts; Multi-plane configurations | Current application and voltage sensing | Optimal inter-electrode spacing critical; Belt size affects image quality [25] |

| Contact Enhancement Solutions | Ultrasound gel; Saline solution; Device-specific contact agents | Improve electrode-skin interface | Reduce impedance variability; Minimize motion artifacts [25] |

| Image Reconstruction Software | EIDORS; Custom MATLAB/Python algorithms; Commercial software | Solve inverse problem; Generate tomographic images | Algorithm choice balances speed/accuracy; Machine learning approaches emerging [1] |

| Signal Processing Tools | Digital filters; Frequency separation algorithms; Artifact correction | Extract respiratory/cardiac signals | Sophisticated filters preserve harmonic content; Pixel-level filtering recommended [25] |

| Synchronization Interfaces | Ventilator data inputs; Physiological monitoring inputs | Correlate EIT with physiological events | Essential for breath-by-breath analysis; Reference maneuvers aid synchronization [25] |

| Calibration References | Spirometry; Plethysmography; CT correlation | Convert arbitrary units to absolute volumes | Point calibrations require repetition with condition changes [25] |

Future Directions and Innovation Pathways

The evolving landscape of EIT research encompasses several promising directions aimed at addressing current limitations and expanding clinical applications:

Hardware Innovations: Next-generation EIT systems incorporate multi-frequency excitation to exploit impedance spectroscopy for enhanced tissue differentiation [1]. Active electrodes with integrated amplifiers minimize cable-induced artifacts, while System-on-Chip (SoC) architectures consolidate signal generation, switching, and data acquisition to improve spatial resolution [1]. These advancements address fundamental limitations in signal fidelity and system portability.

Computational Advances: Machine learning approaches, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and ensemble learning methods, are revolutionizing image reconstruction by modeling non-linear relationships and capturing physical effects overlooked by traditional algorithms [1]. Physics-informed learning represents a particularly promising direction that combines the adaptive power of data-driven approaches with the robustness of physical models [1].

Clinical Protocol Standardization: Recent expert consensus meetings have established standardized recommendations for EIT acquisition, processing, and clinical application [25] [27]. These guidelines promote reproducible research and facilitate the integration of EIT into personalized mechanical ventilation strategies. Ongoing efforts focus on establishing uniform nomenclature and validation methodologies across research centers.

Expanded Clinical Applications: Beyond ventilation monitoring, EIT shows growing promise in perfusion assessment using cardiac-related impedance signals, ventilation-perfusion mismatch quantification, and monitoring novel interventions such as phrenic nerve stimulation [25]. The technology's ability to provide continuous, non-invasive assessment of both ventilation and perfusion simultaneously positions it as a comprehensive pulmonary monitoring tool.