Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering: From Scaffold Design to Clinical Translation and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the pivotal role of biomaterials in tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Biomaterials in Tissue Engineering: From Scaffold Design to Clinical Translation and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the pivotal role of biomaterials in tissue engineering, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of biomaterial science, including the properties of natural, synthetic, and smart polymers. The scope extends to methodological advances in fabrication techniques like 3D and 4D printing, detailed applications across key tissues, and the integration of stem cells. It further addresses critical challenges in immunogenicity, manufacturing, and regulation, and concludes with an analysis of clinical validation, market trends, and future pathways for next-generation biomaterials in regenerative medicine.

The Foundation of Regeneration: Core Principles and Classes of Biomaterials

Biomaterials represent an evolving field at the intersection of materials science, biology, and engineering, serving as a cornerstone for many breakthroughs in healthcare and life sciences [1]. These materials are specifically engineered to interact with biological systems for medical or therapeutic purposes, playing a pivotal role in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine [1]. The fundamental goal of tissue engineering is to merge biology, engineering, and medicine to craft functional replacement tissues and organs [2]. This interdisciplinary approach involves combining biomaterials, cells, and growth factors to regenerate damaged tissues, where cells are sourced from the patient or a donor, combined with a scaffold to provide structural support, and nurtured to form three-dimensional tissues [2].

The performance and success of biomaterials in medical applications depend on their ability to meet specific requirements based on their intended function [1]. These requirements can be categorized into three essential properties: biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioactivity. This triad of properties collectively determines whether a biomaterial can perform effectively in tissue engineering applications, ensuring it supports rather than hinders the regenerative process. Understanding these properties is critical to ensuring that biomaterials can perform their intended function within the human body without causing harm while actively promoting tissue regeneration [1]. As the field advances, these core properties guide the development of next-generation biomaterials that increasingly mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) - the highly sophisticated biological framework that actively orchestrates fundamental cellular processes through integrated biomechanical and biochemical cues [3].

Defining Biocompatibility: From Phenomenology to Host Integration

The Evolution of a Critical Concept

Biocompatibility stands as the defining characteristic of any biomaterial [1]. The term has undergone significant conceptual evolution since its early applications. The first widely accepted definition was ratified at a biomaterials consensus conference in Chester, England in 1986 and published in 1987: "the ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" [4]. This definition was reaffirmed in recent conferences on biomaterial definitions despite its limitations in suggesting assessment methods or improvement strategies [4].

A more contemporary definition emerging from interdisciplinary tissue engineering approaches reframes biocompatibility as "the ability of tissue engineering scaffold or matrix to support the appropriate cellular activity, including the facilitation of molecular and mechanical signaling systems, to optimize tissue regeneration, without eliciting any undesirable local or systemic response in the eventual host" [5]. This evolution in terminology reflects a shift from passive acceptance to active integration, emphasizing the dynamic role biomaterials play in supporting cellular functions essential for tissue regeneration.

Assessment Methodologies and Standards

The assessment of biocompatibility has evolved from early phenomenological observations to standardized toxicological testing. Contemporary biocompatibility evaluation typically follows International Organization for Standardization (ISO) guidelines, particularly the ISO-10993 series, which involves extracting "migratable chemical moieties" from materials and assessing their effects on cells in culture and living research animals [4]. These tests evaluate local and systemic effects in vivo, with implantation studies examining the tissue response over specified periods.

A critical aspect of biocompatibility assessment in tissue engineering involves evaluating the peri-material reaction. In response to host response, implanted material is typically layered with macrophages on the inner zone and fibroblasts and connective tissue on the outer zone [5]. The magnitude of this peri-material reaction and subsequent inflammatory layer formation serves as an index of biocompatibility [5]. For bone tissue engineering applications, biocompatibility also influences the scaffold's osteoinductive and osteoconductive nature [5].

Table 1: Key Standards for Assessing Biocompatibility According to ISO 10993

| Standard Part | Focus Area | Key Assessment Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 10993-1 | Evaluation and testing within a risk management process | Provides framework for biological evaluation of medical devices |

| ISO 10993-3 | Tests for genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and reproductive toxicity | Identifies potential mutagenic and carcinogenic effects |

| ISO 10993-4 | Selection of tests for interactions with blood | Hemocompatibility including thrombosis, coagulation, platelets |

| ISO 10993-5 | Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity | Cell culture tests using mammalian cells |

| ISO 10993-6 | Tests for local effects after implantation | Tissue response to implanted materials in animal models |

| ISO 10993-10 | Tests for skin sensitization and irritation | Identification of potential sensitizers and irritants |

| ISO 10993-11 | Tests for systemic toxicity | Potential toxic effects beyond the implantation site |

The Foreign Body Response and Contemporary Challenges

The introduction of any biomaterial into living tissue triggers a complex sequence of events known as the foreign body response (FBR). This process begins with protein adsorption to the material surface within seconds of implantation, followed by inflammatory cell recruitment, and potentially culminating in the formation of a fibrous capsule that walls off the implant [4]. The FBR represents a significant challenge for many medical devices, as the resulting fibrotic scar can impede device function - inhibiting electrical communication for electrodes, slowing drug transport for delivery systems, impeding analyte diffusion for sensors, and causing deformation or pain in cosmetic implants [4].

Current research focuses on developing "pro-healing" biomaterials that can diminish or eliminate the scar capsule and lead to vascularized, reconstructive healing [4]. These advanced materials represent the next frontier in biocompatibility, moving beyond mere tolerance to active integration with host tissues.

Biodegradability: Programmed Material Lifecycle in Tissue Regeneration

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Biodegradability is a desirable property for biomaterials intended for temporary applications, such as tissue scaffolds or drug delivery systems [1]. Biodegradable materials are designed to break down naturally within the body, either being absorbed or excreted once they have served their purpose. The rate of degradation can be controlled by adjusting the material's composition and structure, ensuring that the biomaterial remains functional for the necessary period before dissolving without causing harm [1].

In tissue engineering, biodegradable scaffolds provide structural support for growing tissues before gradually being replaced by the body's natural tissue [1]. This temporary support function is crucial for guiding tissue regeneration, as the scaffold must maintain mechanical integrity during the initial healing phase while progressively transferring load-bearing responsibilities to the newly formed tissue. The degradation process typically occurs through hydrolysis, enzymatic activity, or cellular processes, with the breakdown products needing to be non-toxic and readily metabolized or excreted by the body.

Material Classes and Degradation Profiles

Various material classes exhibit biodegradable properties suitable for tissue engineering applications. These include natural polymers (e.g., collagen, silk, alginate), synthetic polymers (e.g., polylactic acid [PLA], polyglycolic acid [PGA], polycaprolactone [PCL]), and certain ceramics (e.g., calcium phosphates). Each class offers distinct degradation profiles and mechanical properties that can be tailored to specific applications.

Natural polymers generally demonstrate higher bioactivity and cellular recognition but may present challenges in controlling degradation rates and mechanical properties. Synthetic polymers offer greater control over degradation kinetics and mechanical behavior but may lack inherent bioactivity. Hybrid approaches combining natural and synthetic materials seek to leverage the advantages of both systems.

Table 2: Degradation Profiles of Common Biodegradable Polymers in Tissue Engineering

| Polymer | Degradation Mechanism | Typical Degradation Time | Key Applications | Degradation Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collagen | Enzymatic degradation | 2 weeks - 6 months | Skin regeneration, soft tissue repair | Amino acids |

| Polyglycolic Acid (PGA) | Hydrolysis | 2-4 months | Sutures, tissue scaffolds | Glycolic acid |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Hydrolysis | 6 months - 2 years | Bone fixation devices, scaffolds | Lactic acid |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | Hydrolysis | 2-3 years | Long-term implants, drug delivery | Caproic acid |

| Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) | Hydrolysis | 1-6 months (ratio-dependent) | Drug delivery, temporary scaffolds | Lactic and glycolic acids |

| Chitosan | Enzymatic degradation | 2 weeks - 3 months | Wound healing, cartilage repair | Glucosamine |

Experimental Protocols for Degradation Analysis

Standardized protocols exist for evaluating the degradation behavior of biomaterials in simulated physiological conditions. These typically involve incubating material samples in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 and 37°C, with or without enzymatic additives to simulate in vivo conditions more accurately. Key parameters monitored include:

- Mass Loss Measurement: Samples are periodically removed, dried, and weighed to calculate percentage mass loss over time.

- Molecular Weight Changes: Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) tracks reductions in polymer molecular weight.

- Mechanical Property Decay: Tensile testing, compression testing, or dynamic mechanical analysis monitors the decline in mechanical integrity.

- Morphological Changes: Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) visualizes surface erosion or bulk degradation patterns.

- pH Monitoring: Changes in medium pH indicate acidic or alkaline degradation products.

The degradation profile must be carefully matched to the specific tissue regeneration timeline. For example, bone regeneration scaffolds typically require longer degradation periods (3-6 months) to support mechanical function during healing, while skin regeneration scaffolds may degrade more rapidly (2-4 weeks) as new tissue forms.

Bioactivity: Beyond Passive Function to Biological Dialogue

Defining Bioactive Interactions

Bioactivity refers to the ability of a material to interact with biological tissues in a way that promotes healing, cell attachment, or regeneration [1]. Bioactive materials can stimulate specific biological responses, such as the growth of new tissue or the healing of wounds [1]. Unlike merely biocompatible materials that passively avoid harmful effects, bioactive materials actively participate in biological processes, influencing cellular behavior through controlled interactions at the material-tissue interface.

The development of bioactive materials represents a significant advancement in biomaterials science, as these materials can not only support biological functions but actively enhance the body's natural healing processes [1]. For instance, bioactive glass used in bone implants can release ions that encourage bone formation, while bioactive polymers can promote skin cell growth in wound healing applications [1]. This capacity for active biological engagement positions bioactivity as a crucial property for next-generation tissue engineering scaffolds.

Molecular Mechanisms of Bioactive Materials

Bioactive materials function through several molecular mechanisms to influence cellular behavior and tissue regeneration:

Integrin-Mediated Signaling: Bioactive materials often present specific peptide sequences (e.g., RGD from fibronectin) that engage integrin receptors on cell surfaces [3]. This engagement initiates intracellular signaling cascades that regulate cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation. The activation of integrin signaling begins with ECM ligand binding, which induces conformational changes that promote receptor clustering and the assembly of focal adhesion complexes [3]. These specialized structures serve as mechanical and biochemical signaling hubs, recruiting adaptor proteins including talin, vinculin, and paxillin to bridge the connection between integrins and the actin cytoskeleton [3].

Growth Factor Delivery: Many bioactive scaffolds incorporate growth factors (e.g., BMP-2 for bone formation, VEGF for vascularization) that are released in a controlled manner to direct tissue regeneration.

Ion Release: Certain bioceramics and bioactive glasses release ions (e.g., silicon, calcium, phosphate) that stimulate cellular responses and promote mineralized tissue formation.

Topographical Cues: Nanoscale and microscale surface patterns can influence cell morphology, alignment, and differentiation through contact guidance.

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways activated by integrin engagement with bioactive materials:

Experimental Assessment of Bioactivity

Evaluating the bioactive properties of biomaterials requires a multifaceted approach combining in vitro and in vivo methods:

In Vitro Assessment Protocols:

- Cell Adhesion Assays: Quantifying cell attachment and spreading over time using fluorescence microscopy or colorimetric methods.

- Proliferation Studies: Measuring cell growth rates using MTT, Alamar Blue, or DNA quantification assays.

- Differentiation Analysis: Assessing lineage-specific differentiation through gene expression (qPCR), protein production (immunocytochemistry, Western blot), and functional assays (alkaline phosphatase for osteogenesis, GAG deposition for chondrogenesis).

- Gene Expression Profiling: RNA sequencing or microarray analysis to evaluate global transcriptional responses to material cues.

In Vivo Assessment Protocols:

- Histological Analysis: Tissue sectioning and staining (H&E, Masson's Trichrome, immunohistochemistry) to evaluate tissue integration, cellular infiltration, and matrix deposition.

- Mechanical Integration: Push-out tests or tensile testing to measure bond strength between implant and host tissue.

- Functional Recovery: Assessing restoration of tissue function through biomechanical testing, imaging, or physiological measurements.

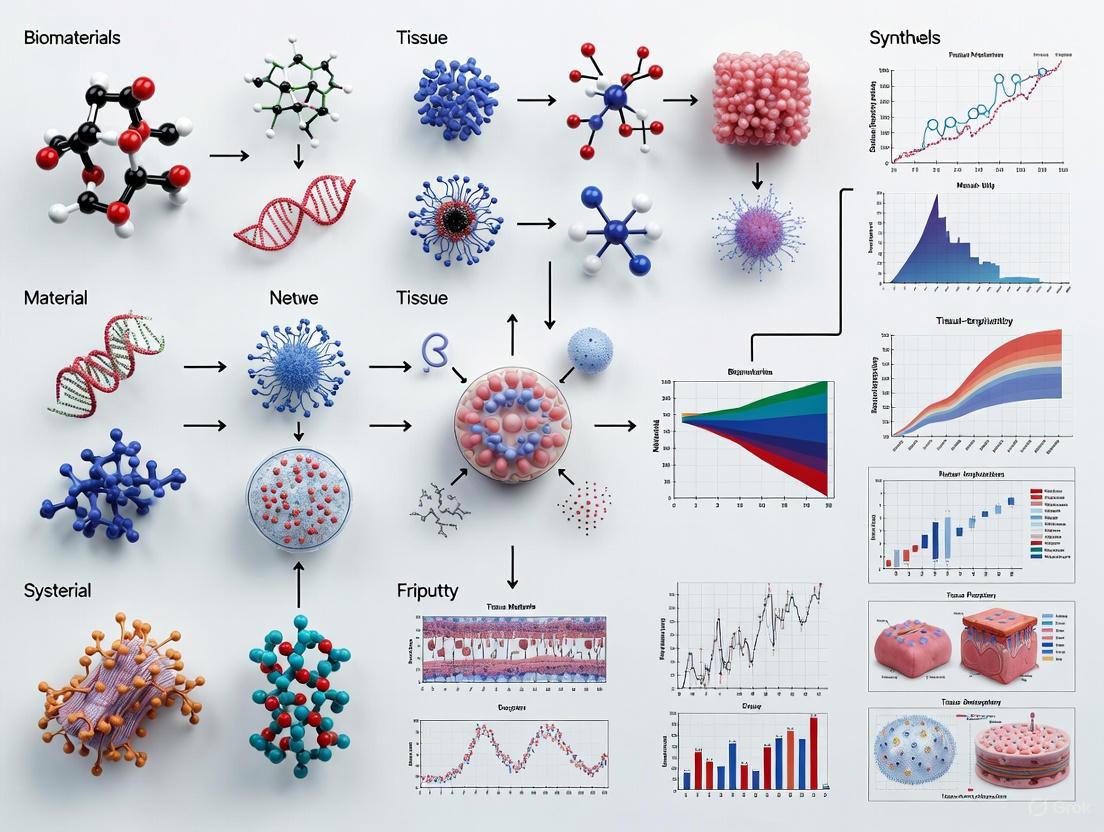

Integrated Workflow for Biomaterial Development and Testing

The development of advanced biomaterials for tissue engineering follows a systematic workflow from conceptualization through characterization to biological validation. The following diagram outlines this comprehensive process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful biomaterials research requires specialized reagents and materials to properly evaluate the triad of key properties. The following table details essential components of the biomaterials research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomaterial Characterization

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in Biomaterials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), osteoblasts, fibroblasts, endothelial cells | Evaluate cell-material interactions, biocompatibility, and bioactivity |

| Molecular Biology Assays | qPCR reagents, ELISA kits, Western blot materials | Assess cellular responses at genetic and protein levels |

| Histological Stains | Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E), Masson's Trichrome, Alizarin Red | Visualize tissue integration and specific matrix components |

| Polymer Synthesis Reagents | Lactide, glycolide, ε-caprolactone monomers, initiators (Sn(Oct)₂) | Synthesize biodegradable polymers with tailored properties |

| Crosslinking Agents | Genipin, glutaraldehyde, carbodiimides (EDC/NHS) | Modify mechanical properties and degradation rates |

| Bioactive Factors | RGD peptides, BMP-2, VEGF, TGF-β3 | Enhance specific biological responses and tissue regeneration |

| Characterization Standards | ISO 10993 series, ASTM standards for biomaterials | Ensure reproducible and comparable evaluation methods |

The triad of biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioactivity represents the fundamental framework for designing effective biomaterials in tissue engineering. These properties are not isolated characteristics but interconnected elements that must be carefully balanced to create successful regenerative therapies. Biocompatibility ensures harmonious existence with living systems, biodegradability provides temporary support that gracefully exits once its function is fulfilled, and bioactivity enables dynamic communication with cells to direct the regenerative process.

As the field advances, we are witnessing a shift from biomaterials that merely avoid harm to those that actively orchestrate regeneration [4]. This evolution is driven by increasingly sophisticated understanding of ECM biology [3] and the molecular mechanisms governing cell-material interactions. The future of biomaterials in tissue engineering lies in developing increasingly intelligent systems that can dynamically respond to physiological cues, selectively direct cellular behavior, and seamlessly integrate with host tissues to restore function. By mastering the interplay between biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioactivity, researchers can create next-generation biomaterials that truly bridge the gap between synthetic constructs and living tissues.

Natural biomaterials, primarily derived from biological sources, play an indispensable role in advancing tissue engineering and regenerative medicine (TE-RM). These materials, which include alginates, celluloses, chitosan, and collagen, serve as scaffolds that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing structural support and biochemical cues that guide tissue regeneration [6]. Their widespread application stems from inherent properties such as excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low immunogenicity. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to these four key natural biomaterials, detailing their fundamental characteristics, mechanisms of action, and practical experimental methodologies. Framed within the broader context of a thesis on biomaterials in tissue engineering research, this document serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, equipping them with the foundational knowledge and protocols needed to leverage these materials in their work.

Fundamental Properties and Comparative Analysis

The utility of a biomaterial is determined by a suite of physicochemical and biological properties. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the key characteristics of alginates, celluloses, chitosan, and collagen.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Natural Biomaterials

| Biomaterial | Source | Key Characteristics | Typical Compressive Modulus | Degradation Timeline | Cell Adhesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | Brown seaweed, bacteria [6] | Hydrophilic, anionic polysaccharide; forms hydrogels via ionic crosslinking [6] | 20–40 kPa (unmodified) [6] | Weeks to months (tunable) [6] | Poor (unless modified with RGD) [6] |

| Cellulose | Plants (CNC, CNF), bacteria (BNC) [7] [8] | High purity, excellent mechanical strength, biocompatibility [8] | High (BNC provides robust scaffolds) [8] | Low degradation in mammals | Moderate |

| Chitosan | Crustacean shells | Cationic polysaccharide, antimicrobial, bioadhesive [7] | <10 kPa (hydrogels) [6] | Tunable via degree of deacetylation | Good (supports stem cell adhesion) [7] |

| Collagen | Animal tissues, recombinant systems [9] | Major ECM protein; excellent biocompatibility and bioactivity [9] | Varies by form and crosslinking | Tunable via crosslinking density | Excellent (native RGD motifs) [9] |

The selection of a biomaterial is highly application-dependent. Alginate is prized for its rapid, mild gelation conditions but often requires composite strategies or chemical functionalization to improve its mechanical strength and cellular interactions [6] [10]. Cellulose nanoparticles, particularly bacterial cellulose (BC), provide exceptional mechanical strength and are ideal for hard tissue regeneration, though their degradation profile can be a limitation [7] [8]. Chitosan offers inherent antimicrobial properties and supports stem cell adhesion, making it suitable for wound healing and soft tissue engineering, though its mechanical strength is relatively low [6] [7]. Collagen, as a native component of the ECM, offers superior bioactivity and cell signaling capabilities. The ratio of its types, particularly Collagen I and III, is critical for tissue function; a lower Col I/III ratio is associated with more flexible, elastic tissues and reduced scarring, as seen in fetal wound healing [9] [11].

Table 2: Impact of Collagen I/III Ratio in Different Tissues

| Tissue/Condition | Typical Collagen I/III Ratio | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Skin | ~4:1 [11] | Provides tensile strength and structural integrity. |

| Fetal Skin | ~1:1 [9] | Promotes regenerative, scarless healing. |

| Blood Vessels | High abundance of Type III [9] | Confers elasticity and distensibility. |

| Hypertrophic Scars | Altered ratio and organization [9] | Leads to disorganized ECM and loss of function. |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Natural biomaterials direct cellular behavior through specific molecular interactions. The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways and structural relationships.

Alginate Functionalization and Cell Signaling

This diagram outlines the process of modifying alginate to make it bioactive and the subsequent integrin-mediated signaling pathway it activates to promote cell survival and proliferation.

Collagen I/III Ratio in Tissue Remodeling

This diagram shows how the ratio of Collagen I to III influences tissue mechanical properties and its therapeutic application in scaffold design.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Preparation of Ionically Crosslinked Alginate Hydrogel

This is a fundamental method for creating alginate hydrogels for cell encapsulation or drug delivery [6] [10].

- Step 1: Solution Preparation. Dissolve high-G content sodium alginate powder in deionized water or physiological buffer (e.g., 0.9% NaCl) to a typical concentration of 1-3% (w/v). Stir continuously until the solution is clear and free of particulates. Sterilize the solution by autoclaving or sterile filtration.

- Step 2: Crosslinking Agent Preparation. Prepare a crosslinking solution containing a divalent cation, most commonly Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂), at a concentration of 50-200 mM in deionized water. Sterilize by filtration.

- Step 3: Gelation via the "Egg-Box" Model.

- Droplet Method: Slowly drip the alginate solution into the crosslinking solution using a syringe pump or pipette. This forms stable, crosslinked alginate beads. Incubate for 10-15 minutes to ensure complete gelation.

- Bulk Gel Method: For larger hydrogels, mix the alginate and crosslinking solutions rapidly and thoroughly. The gel will form within seconds to minutes.

- Step 4: Post-Processing. Wash the resulting hydrogel three times with sterile buffer or culture medium to remove excess crosslinking ions and to equilibrate the pH. The hydrogel is now ready for cell culture, mechanical testing, or further modification.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Chitosan-Alginate Composite Scaffold

Combining chitosan and alginate leverages the benefits of both materials, creating a polyelectrolyte complex with improved stability and bioactivity [6] [10].

- Step 1: Polymer Solution Preparation.

- Prepare a 2% (w/v) chitosan solution by dissolving chitosan in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution. Stir until fully dissolved.

- Prepare a 2% (w/v) sodium alginate solution in deionized water as described in Protocol 4.1.

- Step 2: Composite Formation. Mix the chitosan and alginate solutions in a desired volume ratio (e.g., 1:1) under constant stirring. The oppositely charged polymers will form a polyelectrolyte complex, which may result in a precipitate or a viscous solution.

- Step 3: Scaffold Fabrication. The composite mixture can be processed into various forms:

- Porous Scaffolds: Pour the mixture into a mold and freeze at -20°C overnight, then lyophilize to create a porous sponge.

- Hydrogels: Induce further crosslinking by exposing the mixture to a CaCl₂ solution or by raising the pH to neutralize the chitosan.

- Step 4: Characterization. Characterize the scaffold's morphology using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), its mechanical properties via compression testing, and its biological performance through cell viability assays (e.g., with MSCs).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful research with natural biomaterials requires a suite of key reagents and tools. The following table details essential items for a laboratory working in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomaterial Research

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| High-Guluronic Acid (High-G) Alginate | Forms stiffer, more stable hydrogels via ionic crosslinking, ideal for load-bearing tissue models [6] [10]. |

| Recombinant Human Type III Collagen (rhCol III) | Provides a safe, xenogeneic-free collagen source with customizable properties for scaffolds that promote regenerative healing [9]. |

| Bacterial Nanocellulose (BNC) | Serves as a mechanically robust, highly pure scaffold material for engineering hard tissues like bone and cartilage [7] [8]. |

| RGD Peptide | A critical biochemical modifier; covalently grafted onto alginate to confer cell-adhesive properties [6]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | The most common ionic crosslinker for alginate hydrogels, enabling rapid gelation under mild conditions [6] [10]. |

| Methacrylated Alginate (SAMA) | A chemically modified alginate for photopolymerization; allows fabrication of stable, tunable hydrogels via UV light [10]. |

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | A primary cell type used in TE-RM; their interaction with biomaterial scaffolds is a standard model for evaluating regenerative potential [7]. |

Alginates, celluloses, chitosan, and collagen represent a powerful toolkit for addressing complex challenges in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. While each material has distinct advantages and limitations, ongoing research focused on chemical modification, composite formation, and a deeper understanding of molecular interactions with cells is rapidly advancing the field. The translation of these biomaterials from laboratory research to clinical applications hinges on rigorous, standardized experimental methodologies and a clear comprehension of their structure-function relationships. As the field progresses, these natural biomaterials will undoubtedly remain cornerstone elements in the development of next-generation therapeutic strategies for tissue repair and regeneration.

Synthetic biodegradable polymers have emerged as cornerstone materials in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, providing a versatile platform for creating scaffolds that mimic the native extracellular matrix (ECM). Among these, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polylactic acid (PLA) stand out due to their tunable properties, biocompatibility, and predictable degradation profiles. These polymers serve as temporary structural templates that support cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation while gradually degrading to be replaced by newly formed tissue [3] [12]. The fundamental advantage of these synthetic materials lies in their precise engineerability—researchers can systematically modify their chemical composition, molecular weight, and copolymer ratios to control mechanical strength, degradation kinetics, and bioactivity for specific therapeutic applications ranging from bone regeneration to drug delivery systems [13].

The significance of these biomaterials extends beyond their structural function. They actively participate in the regenerative process by providing biochemical cues through surface functionalization, controlling the release of therapeutic agents, and interacting with cellular components through integrin-mediated signaling pathways [3]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of PLGA, PCL, and PLA, focusing on their structure-property relationships, advanced fabrication methodologies, and experimental protocols for characterizing their performance in biomedical applications.

Material Properties and Characterization

The functional performance of PLGA, PCL, and PLA in tissue engineering applications is governed by their distinct chemical compositions, thermal behaviors, and degradation mechanisms. Understanding these properties enables researchers to select and tailor materials for specific regenerative medicine applications.

Comparative Analysis of Polymer Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of PLGA, PCL, and PLA

| Property | PCL | PLA | PLGA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition | Semi-crystalline aliphatic polyester from ε-caprolactone monomers [13] | Aliphatic polyester derived from L-lactide and D-lactide isomers [13] | Copolymer of lactic acid (LA) and glycolic acid (GA) with tunable ratios [13] |

| Crystallinity | 20-33% (high crystallinity) [13] | Varies by D/L isomer ratio (low D = crystalline, high D = amorphous) [13] | Amorphous to semi-crystalline depending on LA:GA ratio [13] |

| Melting Point (°C) | 58-61 [13] | 150-160 [13] | Not well-defined; varies by LA:GA ratio, typically amorphous [13] |

| Glass Transition (°C) | ≈ -60 [13] | ≈ 60 [13] | 40-60 (higher LA → higher Tg) [13] |

| Mechanical Properties | Flexible; low tensile strength; strength increases with crystallinity [13] | Tensile strength: 50-70 MPa; Elastic modulus: 3-4 GPa [13] | Varies with LA:GA ratio; generally lower tensile strength than PLA [12] |

| Degradation Time | Very slow (months to years) [13] [14] | Intermediate (months to years) [13] | Fastest at 50:50 LA:GA ratio (weeks to months) [13] |

| Key Characteristics | High hydrophobicity, slow degradation, excellent ductility [13] [14] | High strength, stiffness, degradation rate depends on crystallinity [13] | Precise degradation control via LA:GA ratio, tunable hydrophilicity [13] |

Degradation Mechanisms and Drug Release Kinetics

The degradation of these polyesters occurs primarily through hydrolysis of their ester bonds, but the rates and patterns differ significantly based on their crystallinity, hydrophobicity, and copolymerization ratios [13]. PCL's high crystallinity and hydrophobicity limit water penetration, resulting in very slow degradation that makes it suitable for long-term drug release (several months to years) and applications requiring extended structural support [13] [14]. PLA degrades via non-enzymatic hydrolysis, with rates varying from months to years depending on its crystallinity, molecular weight, and processing history [13]. PLGA offers the most tunable degradation profile, with the 50:50 LA:GA ratio exhibiting the fastest degradation due to enhanced water absorption [13].

The degradation behavior directly influences drug release kinetics. PCL's hydrophobic nature and slow degradation suppress initial burst release and enable consistent sustained release over extended periods [13]. PLA provides an intermediate release profile that can be controlled from days to months through processing parameters and molecular weight adjustments [13]. PLGA's drug release pattern can be precisely engineered by varying the LA:GA ratio, with higher glycolide content accelerating release and higher lactide content favoring sustained delivery [13]. Additionally, the hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity of incorporated drugs significantly influences their release profiles from these polymer matrices [13].

Figure 1: Degradation Pathways of Synthetic Polymers. This diagram illustrates the hydrolytic degradation process common to PLGA, PCL, and PLA, highlighting key influencing factors and material-specific outcomes that determine their performance in tissue engineering applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of 3D-Printed PLGA/nHA/GO Composite Scaffolds

The development of bone tissue engineering scaffolds using low-temperature 3D printing and freeze-drying techniques represents a sophisticated approach to creating functional constructs for bone defect repair [15].

Materials and Reagents:

- PLGA (LA/GA = 75/25; Hangzhou Regenovo Biotechnology) as the structural matrix [15]

- nHA (nano-hydroxyapatite, 200 nm particle size; Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology) to replicate bone's inorganic composition [15]

- GO (graphene oxide; Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology) to enhance mechanical properties and bioactivity [15]

- 1,4-Dioxane (Shanghai Macklin Biochemical) as solvent for polymer dissolution [15]

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for degradation studies [15]

Scaffold Fabrication Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve PLGA pellets (2g) in 15 mL 1,4-dioxane under magnetic stirring for 30 minutes at room temperature [15].

- Composite Formulation: For PLGA/nHA/GO group, add nHA (0.5g) and GO (0.01g) to the base PLGA solution. Use vortex dispersion for 1 minute followed by magnetic stirring until complete homogenization (mass ratios: PLGA:nHA = 4:1; nHA:GO = 100:2) [15].

- 3D Printing Parameters: Utilize a pre-cooled 3D printer (Bio-Architect wS) with optimized parameters:

- Post-processing: Immediately transfer printed scaffolds to -80°C refrigerator for 2 hours, followed by freeze-drying for 24 hours [15].

- Sterilization: Immerse scaffolds in 75% ethanol with ultraviolet light irradiation for 3 hours, then wash with PBS to remove residual ethanol [15].

Characterization Methods:

- Mechanical Testing: Perform compression testing according to ASTM D695 at a compression rate of 1 mm/min with 60% strain rate [15].

- Degradation Study: Immerse scaffolds in PBS (pH 7.4) and measure mass loss at predetermined time points using the formula: Degradation rate (mg/w) = (M1 - M2)/2w, where M1 is initial mass and M2 is mass at time point [15].

- Water Absorption: Measure dry mass (m1), immerse in deionized water, then measure wet mass (m2) at 3, 6, 9, and 12 hours. Calculate water absorption as: (m2 - m1)/m1 × 100% [15].

In Vivo Evaluation of 3D-Printed PCL Tracheal Scaffolds

The assessment of medical-grade versus research-grade PCL in rabbit tracheal defect models provides critical insights into the importance of material selection for specific clinical applications [16].

Experimental Design:

- Scaffold Fabrication: Manufacture customized scaffolds for rabbit segmental defects using extrusion-based 3D printing with research-grade (RG) and medical-grade (MG) PCL [16].

- Surgical Implantation: Transplant scaffolds into tracheal defects in rabbit models following approved IACUC protocols (The Catholic University of Korea, 2020-0213-01) [16].

- Evaluation Timeline: Excise transplanted areas after 6 months for analysis [16].

Analytical Methods:

- Mechanical Characterization: Assess ultimate stress and strain of explanted scaffolds to compare strength and ductility retention [16].

- Molecular Weight Analysis: Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to compare molecular weight changes before and after transplantation and after gamma radiation sterilization [16].

- Histological Evaluation: Employ tissue staining techniques to analyze mucosal tissue regeneration and overall tissue reconstruction at implantation site [16].

- Endoscopic Examination: Monitor tissue integration and structural integrity in vivo [16].

Key Findings: Medical-grade PCL scaffolds demonstrated superior ultimate stress, strain, and tissue reconstruction compared to research-grade scaffolds, with better strength, ductility, and mucosal regeneration. However, MG PCL degraded more rapidly in vivo, as indicated by significant molecular weight reduction post-transplantation [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Polymer Scaffold Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA Polymers | Structural matrix for scaffolds with tunable degradation | LA:GA ratios (e.g., 75:25); inherent viscosity varies by application | Hangzhou Regenovo Biotechnology [15] |

| Medical-grade PCL | High-purity polymer for implantation studies | Controlled molecular weight distribution; sterilizable | Perstorp (CAPA 6400) [16] [14] |

| Nano-Hydroxyapatite (nHA) | Bone mineral mimic for osteoconduction | 200 nm particle size; enhances bioactivity | Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology [15] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Mechanical reinforcement and bioactivity enhancement | Specific surface area; functional group density | Shanghai Yien Chemical Technology [15] |

| 1,4-Dioxane | Solvent for polymer processing | Anhydrous grade for solution-based fabrication | Shanghai Macklin Biochemical [15] |

| Gamma Irradiation | Terminal sterilization method | Standard dosage (25 kGy); maintains polymer integrity | Contract sterilization services [16] |

| Gel Permeation Chromatography | Molecular weight distribution analysis | Tetrahydrofuran as mobile phase for polyesters | Waters, Agilent Technologies [16] |

Advanced Applications and Functional Design Strategies

Porosity Optimization for Tissue Engineering Scaffolds

The strategic design of scaffold architecture, particularly porosity, plays a critical role in determining the success of tissue engineering constructs. Research has demonstrated that porosity directly influences mechanical properties, cellular responses, and microbial interactions [17].

Table 3: Effect of Porosity on PLA Scaffold Properties

| Porosity Level | Tensile Strength | Human Skin Fibroblast Viability | Bacterial Adhesion Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 4 MPa | Moderate proliferation | Species-specific adherence patterns |

| 40% | 8 MPa | Good proliferation | S. aureus peak adhesion (40-60%) |

| 60% | 8 MPa | High viability | S. aureus peak adhesion (40-60%) |

| 80% | 16 MPa | Highest viability | P. aeruginosa maximum adhesion |

| 100% | 28 MPa | Moderate viability | S. epidermidis and E. coli peak adhesion |

Studies have revealed that intermediate porosity levels (60-80%) create an optimal balance between mechanical integrity and biological performance. PLA scaffolds with 80% porosity demonstrated the highest human skin fibroblast viability while maintaining sufficient tensile strength (16 MPa) for many soft tissue applications [17]. The relationship between porosity and bacterial adhesion showed species-specific responses, informing infection-resistant scaffold design strategies [17].

Polymer Blending for Soft Tissue Reconstruction

The combination of PLA and PCL in knitted scaffolds has shown significant promise for soft tissue engineering applications, particularly in adipose tissue reconstruction [14]. By adjusting the PLA/PCL ratio, researchers can precisely control the mechanical properties and degradation profiles to match specific tissue requirements.

PLA90/PCL10 scaffolds maintain better structural integrity and stiffness, making them suitable for applications requiring mechanical support during the initial healing phase. These scaffolds demonstrated superior performance in vivo with enhanced vascularization and reduced macrophage infiltration in rat models [14].

PLA70/PCL30 scaffolds with higher PCL content exhibit enhanced elasticity and porosity, facilitating cell infiltration and nutrient transport. These scaffolds showed excellent biocompatibility in vitro but slightly reduced efficacy in supporting adipogenic differentiation compared to PLA90/PCL10 variants [14].

The fabrication of these scaffolds via melt-spinning and knitting techniques enables the production of three-dimensional porous structures with multiscale porosity and elasticity tailored to soft tissue properties [14]. This approach represents a significant advancement over traditional fabrication methods like electrospinning and FDM, particularly for applications requiring flexibility and adaptability to anatomical contours.

Figure 2: Biomaterial Design Framework. This diagram outlines the strategic approach to developing polymer-based scaffolds for specific tissue engineering applications, highlighting the interconnected decision points from material selection to functional outcomes.

Synthetic polymers PLGA, PCL, and PLA continue to evolve as fundamental building blocks in tissue engineering, offering unparalleled versatility through their tunable properties and processing adaptability. The strategic selection and combination of these materials enable researchers to create customized scaffolds that address specific clinical challenges, from load-bearing bone defects to delicate soft tissue reconstruction. Medical-grade materials have demonstrated superior performance in vivo compared to research-grade equivalents, highlighting the importance of material quality in translational research [16]. The integration of bioactive components such as nano-hydroxyapatite and graphene oxide further enhances the functionality of these polymer systems, creating composite constructs that more closely mimic the native tissue environment [15].

Future developments in this field will likely focus on smart polymer systems with responsive degradation profiles, advanced fabrication techniques for creating vasculature networks, and personalized scaffolds based on patient-specific imaging data. As research progresses, the continued refinement of PLGA, PCL, and PLA-based technologies will undoubtedly expand their impact in regenerative medicine, offering new solutions for complex tissue repair and regeneration challenges.

Inorganic and metallic biomaterials represent a cornerstone of modern tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. These materials are engineered to interact with biological systems, providing structural support, guiding tissue regeneration, and actively participating in the healing process. Within this domain, calcium phosphates, bioactive glasses, and titanium alloys have emerged as three pivotal classes of materials, each offering a unique combination of properties that make them indispensable for clinical applications. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these materials, focusing on their properties, mechanisms of action, and experimental methodologies relevant to researchers and drug development professionals. Framed within the broader thesis on the role of biomaterials in tissue engineering research, this review underscores how these materials transcend their traditional passive roles to actively orchestrate biological responses for enhanced tissue repair and integration.

Calcium Phosphates

Properties and Classification

Calcium phosphates (CaPs) are a family of bioceramics that closely mimic the mineral composition of native bone, making them one of the most prominent materials for bone tissue regeneration [18] [19]. Their primary advantage lies in their bioactivity, osteoconductivity, and tunable resorption rates. The biological performance of CaPs is highly dependent on their phase composition, stoichiometry, and crystallinity, which are directly influenced by the synthesis method and parameters [18].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Calcium Phosphates Used in Biomedicine

| Material | Chemical Formula | Ca/P Ratio | Key Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyapatite (HAp) | Ca₁₀(PO₄)₆(OH)₂ | 1.67 | High bioactivity, osteoconductivity, chemical stability, slow degradation | Bone defect fillers, coatings for metal implants, dental applications [18] [20] |

| β-Tricalcium Phosphate (β-TCP) | Ca₃(PO₄)₂ | 1.50 | Biodegradable, osteoconductive, higher resorption rate than HAp | Bioresorbable bone grafts, bone cements [18] [20] |

| Biphasic Calcium Phosphate (BCP) | Mixture of HAp and β-TCP | 1.50-1.67 | Controllable degradation/bioactivity ratio via HAp/β-TCP ratio | Bone tissue engineering scaffolds [18] [20] |

| Amorphous Calcium Phosphate (ACP) | Non-stoichiometric | 1.15-1.67 | High reactivity, lack of long-range order | Precursor for bone mineral, component in composite biomaterials [18] |

Synthesis and Experimental Protocol

The properties of calcium phosphates can be precisely controlled through the synthesis route. The following is a detailed protocol for the acid-base precipitation method, a common wet chemical technique [18].

Protocol: Synthesis of HAp Powders via Acid-Base Precipitation

- Objective: To synthesize stoichiometric hydroxyapatite (Ca/P = 1.67) powders with controlled morphology and phase purity.

Principle: The method involves the neutralization reaction between a calcium source and a phosphorus source under controlled pH, leading to the precipitation of HAp.

Materials and Reagents:

- Calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂)

- Orthophosphoric acid (H₃PO₄), 0.3 M

- Ammonia water (NH₄OH, 25%) for pH control

- Deionized water

Equipment:

- Laboratory stirrer with heating mantle

- pH meter

- Centrifuge

- Drying oven

- High-temperature furnace (for calcination, if required)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Reactants: Suspend an appropriate mass of Ca(OH)₂ in 500 mL of deionized water to create a slurry. The mass is calculated based on the desired final Ca/P molar ratio (e.g., 1.67 for HAp). Simultaneously, prepare 500 mL of 0.3 M H₃PO₄ solution.

- Precipitation Reaction: Gradually add the H₃PO₄ solution to the Ca(OH)₂ suspension under constant stirring. The addition rate should be slow to avoid localized precipitation and ensure homogeneity.

- pH Control: Maintain the reaction pH at a constant value (typically between 9-11) by the dropwise addition of 25% ammonia water throughout the synthesis. Precise pH control is critical for obtaining the desired phase composition.

- Ageing: After complete addition, continue stirring the suspension for a further 12-24 hours at room temperature to allow for complete crystal maturation.

- Washing and Separation: Separate the precipitate from the mother liquor by centrifugation. Wash the precipitate repeatedly with deionized water until the supernatant reaches a neutral pH.

- Drying and Calcination: Dry the washed precipitate in an oven at 80-100°C for 24 hours. The resulting powder can be further calcined in a furnace at high temperatures (e.g., 800-1100°C) to improve crystallinity, if required for the application.

Characterization: The synthesized powder should be characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) for phase identification, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) for functional groups, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology, and Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) analysis for determining the exact Ca/P ratio [18].

Signaling Pathways in Bone Regeneration

Calcium phosphates promote bone healing through direct interaction with the biological environment. They release calcium (Ca²⁺) and phosphate (PO₄³⁻) ions, which are known to activate intracellular signaling cascades that promote osteogenic differentiation [3]. A key mechanism involves integrin-mediated signaling. The adsorbed proteins on the CaP surface facilitate cell adhesion through integrin receptors (e.g., αvβ3, α5β1), leading to the formation of focal adhesion complexes and activation of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK). This triggers downstream pathways such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt, which regulate gene expression for cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation into osteoblasts [3]. Furthermore, the released ions can influence the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, another critical regulator of osteogenesis.

CaP-Induced Osteogenic Signaling Pathway

Bioactive Glasses

Composition and Bioactivity Mechanism

Bioactive glasses (BGs) are a class of surface-reactive bioceramics known for their ability to form a strong bond with both hard and soft tissues [21]. The bioactivity mechanism of silicate-based BGs, such as the pioneering 45S5 Bioglass, involves a well-defined series of surface reactions when implanted.

Table 2: Common Bioactive Glass Compositions (mol%)

| Glass Type | SiO₂ | P₂O₅ | CaO | Na₂O | CaF₂ | B₂O₃ | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45S5 | 45.0 | 6.0 | 24.5 | 24.5 | - | - | Gold standard, high bioactivity [21] |

| 58S | 58.2 | 9.2 | 32.6 | - | - | - | Sol-gel derived, high surface area [21] |

| 13-93 | 53.0 | 4.0 | 20.0 | 6.0 | - | - | Contains K₂O and MgO, for bone scaffolds [21] |

| 13-93B3 | - | 3.7 | 18.5 | 5.5 | - | 56.6 | Borate-based, fast degradation [21] |

The sequence of events leading to bioactivity is as follows:

- Rapid Ion Exchange: Na⁺ or other network modifiers from the BG exchange with H⁺ from the surrounding fluid, leading to a local increase in pH.

- Silica Hydrolysis: Breakdown of the silica network occurs, forming silanol (Si-OH) groups on the surface.

- Polycondensation: Silanol groups condense to form a porous silica-rich gel layer.

- Precipitation: Ca²⁺ and PO₄³⁻ ions from the glass and body fluid migrate to the surface, forming an amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) layer.

- Crystallization: The ACP layer incorporates hydroxyl and carbonate ions from the fluid and crystallizes into a bone-like carbonated hydroxyapatite (HCA) layer.

This HCA layer is responsible for the chemical bonding with living tissue [21]. Borate and phosphate-based BGs follow a similar but often faster conversion process, where the glass network former (e.g., B₂O₃) dissolves completely, leading to direct HA precipitation [21].

Experimental Workflow: Sol-Gel Synthesis

The sol-gel process allows for the production of BGs with high purity, homogeneity, and controlled porosity at lower temperatures than the traditional melt-quenching route.

Sol-Gel Synthesis of Bioactive Glass

Protocol: Sol-Gel Synthesis of 58S Bioactive Glass (60 mol% SiO₂, 36 mol% CaO, 4 mol% P₂O₅)

Materials and Reagents:

- Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) - SiO₂ precursor

- Triethyl phosphate (TEP) - P₂O₅ precursor

- Calcium nitrate tetrahydrate (Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O) - CaO precursor

- Deionized water

- Nitric acid (HNO₃) or Ammonia (NH₄OH) as catalyst

- Ethanol

Equipment:

- Polypropylene beaker with sealed lid

- Magnetic stirrer

- Drying oven

- High-temperature furnace

Procedure:

- Hydrolysis of TEOS: Add TEOS to a mixture of deionized water and ethanol (as a mutual solvent) under vigorous stirring. Add a few drops of nitric acid to catalyze the hydrolysis reaction (pH ~1-2). Stir for 1 hour.

- Addition of TEP: Add TEP to the solution and continue stirring for another 45 minutes.

- Addition of Calcium Nitrate: Add the calcium nitrate tetrahydrate to the solution. Stir until it is completely dissolved.

- Gelation: Seal the container and allow the mixture to gel at room temperature. This process may take several days.

- Aging: Once gelled, the monolith is aged in its own pore solution (or a similar solvent) for 24-48 hours to strengthen the gel network.

- Drying: Carefully transfer the aged gel to a drying oven and dry slowly at 60-120°C for several days to remove all liquid and form a "xerogel."

- Thermal Stabilization: Heat the xerogel in a furnace to a temperature between 600-700°C at a controlled heating rate. This step is crucial to remove residual nitrates and organic groups and to stabilize the porous glass structure without crystallizing it.

Titanium and Its Alloys

Properties and Classification

Titanium and its alloys are the dominant metallic biomaterials in orthopedics and dentistry due to their exceptional corrosion resistance, high specific strength, and excellent biocompatibility [22] [23] [24]. A key feature is the spontaneous formation of a protective, adherent surface oxide layer (primarily TiO₂), which is responsible for their passivity and bio-inertness in the physiological environment [22].

Table 3: Classification and Properties of Titanium-Based Biomaterials

| Alloy Type | Alloy Examples | Phases Present | Key Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercially Pure Ti (cpTi) | Grade 1-4 | α | Excellent corrosion resistance, biocompatibility, lower strength | Dental implants, non-load bearing components [22] |

| (α + β) Alloys | Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) | α + β | High strength, good fatigue resistance | Load-bearing orthopedic implants (hip stems, bone plates) [22] [24] |

| Near-β / β Alloys | Ti-13Nb-13Zr, Ti-12Mo-6Zr-2Fe | Predominantly β | Lower Young's Modulus (~55-80 GPa), better strain compatibility with bone | Next-generation orthopedic implants to reduce stress shielding [23] [24] |

A primary driver of titanium's success in bone applications is osseointegration—the direct structural and functional connection between living bone and the implant surface [22]. The native titanium oxide surface is conducive to bone apposition, and this process can be significantly enhanced through surface modifications like sandblasting, acid-etching, or the application of a CaP coating [22] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomaterials Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| L929 Mouse Fibroblasts | Biocompatibility and cytotoxicity testing according to ISO 10993 standards [18]. | Evaluating the biological tolerance of newly synthesized CaP powders [18]. |

| hFOB 1.19 Human Osteoblasts | Assessing osteoconductivity and cell-material interactions specific to bone. | Measuring alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and osteogenic gene expression on Ti surfaces [18]. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | In vitro bioactivity assessment of materials. | Testing the ability of bioactive glass to form a hydroxyapatite layer on its surface [21]. |

| Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 / DMEM | Cell culture media for maintaining and growing mammalian cells. | Standard culture of L929 fibroblasts and other cell lines for biological assays [18]. |

| 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) | Colorimetric assay for measuring cell metabolic activity and proliferation. | Quantifying the viability of cells cultured in the presence of biomaterial extracts [18]. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Potent immune stimulant; used to induce an inflammatory response in cell cultures. | Activating the NF-κB pathway in immune cells to study the immunomodulatory properties of BGs [18]. |

Calcium phosphates, bioactive glasses, and titanium alloys each play a distinct yet complementary role in advancing tissue engineering research. Calcium phosphates offer unmatched biomimicry of bone mineral, bioactive glasses provide unparalleled surface reactivity and bonding capacity, and titanium alloys deliver the necessary mechanical robustness for load-bearing applications. The ongoing research and development in this field are increasingly focused on creating smart, composite, and multifunctional materials that not only provide structural support but also actively direct the regenerative process through controlled ion release, surface engineering, and the incorporation of biological molecules. As our understanding of the biological signaling pathways influenced by these materials deepens, the next generation of inorganic and metallic biomaterials will be precisely engineered to resolve complex clinical challenges, from chronic wound healing to the regeneration of large bone defects, thereby fulfilling their critical role in the future of regenerative medicine.

The field of tissue engineering has progressively shifted from using static, passive biomaterials to dynamic, interactive systems that actively participate in the healing process. Smart biomaterials represent a paradigm shift in this domain, engineered to sense and respond to specific physiological or external stimuli in a predictable manner. These stimuli-responsive systems—reacting to temperature, pH, magnetic fields, and other cues—are revolutionizing therapeutic strategies by enabling unprecedented spatiotemporal control over tissue regeneration processes. The evolution toward four-dimensional (4D) materials, which incorporate time as a transformative dimension, allows fabricated constructs to dynamically change their shape or function post-implantation, more closely mimicking the living, adaptive nature of native biological tissues [25].

The core principle underpinning smart biomaterials is their nonlinear feedback to minimal environmental changes, resulting in pronounced alterations in their physical properties, such as shape, volume, solubility, or conformational structure [26] [27]. This responsiveness is critical for advancing tissue engineering beyond static scaffolds to systems that can guide complex tissue morphogenesis, deliver bioactive agents on demand, and integrate seamlessly with the host's physiology. By leveraging characteristic signals of specific tissue microenvironments—such as the slightly acidic pH of tumor tissue or inflamed wounds, or the temperature gradients associated with diseased states—these materials achieve targeted, localized therapeutic action, thereby maximizing efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [28] [29]. The integration of these intelligent systems is paving the way for a new era of personalized and adaptive regenerative medicine.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Stimuli Responsiveness

Smart biomaterials achieve their dynamic functionality through carefully engineered molecular architectures and material compositions that transduce an external signal into a functional output. The mechanisms vary significantly across different stimulus types.

Temperature-Responsive Mechanisms

Temperature-responsive polymers undergo reversible phase transitions at a specific temperature known as the lower critical solution temperature (LCST). Below the LCST, the polymer chains are hydrated and expanded, while above the LCST, they dehydrate and collapse into a hydrophobic, collapsed state. A quintessential example is Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm), with an LCST of approximately 32°C [26]. This property is exploited for cell-sheet engineering and drug delivery, where a slight increase from ambient to body temperature triggers material aggregation or release. The LCST can be precisely tuned by copolymerizing with more hydrophilic or hydrophobic monomers [30] [26].

pH-Responsive Mechanisms

pH-sensitive materials contain ionizable functional groups (weak acids or bases) that accept or donate protons in response to changes in environmental pH. Common ionizable groups include carboxylic acids (e.g., in poly(acrylic acid)), which deprotonate at higher pH, and tertiary amines (e.g., in poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate)), which protonate under acidic conditions [28] [25] [29]. The change in ionization state alters the polymer's charge density, leading to dramatic shifts in chain conformation, solubility, and swelling ratio. This mechanism is particularly useful for targeting specific physiological compartments like the acidic tumor microenvironment (pH ~6.5), endosomes (pH ~5.5-6.0), or lysosomes (pH ~4.5-5.0) [28] [29].

Magneto-Responsive Mechanisms

Magneto-responsive materials are typically composite systems that incorporate magnetic fillers such as iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) into a polymer matrix (e.g., shape-memory polymers or hydrogels) [30]. When exposed to an alternating magnetic field, these nanoparticles generate heat through hysteresis loss or Neel relaxation, which can be used to trigger shape recovery in shape-memory polymers or accelerate drug release from a hydrogel. Alternatively, static magnetic fields can exert mechanical forces on the embedded particles, causing macroscopic deformation or alignment of the material [30]. This allows for non-invasive, remote control over material behavior from outside the body.

Figure 1: Mechanisms of stimulus-responsive behavior in smart biomaterials, showing how different environmental signals trigger distinct material changes that enable specific therapeutic applications.

Material Classes and Their Responsive Behaviors

Shape Memory Polymers (SMPs)

SMPs are a class of stimuli-responsive smart materials capable of recovering from a temporary, deformed shape to their original, permanent configuration upon application of a specific external stimulus. Their molecular architecture typically consists of a fixed phase (netpoints) and a reversible phase (molecular switches) [30]. The fixed phase determines the permanent shape, while the reversible phase softens and allows deformation upon stimulus exposure and solidifies upon stimulus removal to fix the temporary shape. Common triggers include temperature, light, electricity, or magnetic fields. In biomedical applications, SMPs are particularly promising for minimally invasive implantation, where a compact, temporary device can be inserted through a small incision and then expanded to its functional shape in situ [30]. For instance, cardiac occluders made from SMPs can be fixed into a miniaturized configuration for delivery and subsequently recover to their original volumetric state to block pathological blood flow channels upon reaching body temperature [30].

Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels (SRHs)

SRHs are three-dimensional, crosslinked polymer networks that can absorb large amounts of water while maintaining their structure. Their swelling/deswelling behavior, mechanical properties, and permeability can be drastically altered by environmental cues. Physical hydrogels are formed by reversible, non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic assembly, and host-guest supramolecular interactions, which can impart self-healing properties [27]. Chemical hydrogels are formed by permanent covalent crosslinks (e.g., via "click" chemistry or photo-polymerization), providing greater mechanical stability [27]. A key application is in drug delivery, where a hydrogel can be designed to release its payload in response to a specific tissue's pH or temperature. For example, an injectable Pluronic F127 hydrogel undergoes sol-gel transition near body temperature, forming a depot for sustained drug release [26] [27].

Liquid Crystal Elastomers (LCEs)

LCEs synergistically integrate the molecular alignment of liquid crystals with the elastic properties of polymer networks. This unique combination allows them to demonstrate large, reversible deformations and chromic transitions upon exposure to diverse external stimuli like heat or light [30]. The direction and magnitude of their actuation are programmed by the alignment of the liquid crystal mesogens during fabrication. Their energy-transducing capability, inherent responsiveness, and programmable actuation trajectories position them as frontrunners in next-generation adaptive biomedical systems, particularly for bioinspired artificial muscles and dynamic tissue scaffolds that can provide mechanical cues to cells [30].

Table 1: Key Classes of Smart Biomaterials and Their Characteristics

| Material Class | Stimulus | Key Mechanism | Common Materials | Tissue Engineering Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape Memory Polymers (SMPs) | Temperature, Light, Magnetic Field | Phase transition (glass/rubber) in reversible phase; elasticity of netpoints | Polyurethanes, Poly(ε-caprolactone), Polyvinyl alcohol [30] | Minimally invasive implants, cardiac occluders, self-tightening sutures [30] |

| Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels (SRHs) | pH, Temperature, Ionic Strength, Light | Swelling/deswelling via ionization, LCST transition, bond cleavage | PNIPAm, Chitosan, Alginate, Poly(acrylic acid), GelMA [25] [27] | Drug delivery depots, 3D cell culture scaffolds, injectable fillers [25] [27] |

| Liquid Crystal Elastomers (LCEs) | Temperature, Light | Reversible change in mesogen orientation coupled with network elasticity | Polysiloxane-based LCEs, Acrylate-based LCEs [30] | Bioinspired actuators, dynamic scaffolds for muscle tissue [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Synthesis of a pH-Responsive Hydrogel for Drug Delivery

Objective: To synthesize an injectable, pH-sensitive hydrogel based on chitosan and poly(acrylic acid) for controlled drug release in the acidic tumor microenvironment.

Materials:

- Chitosan (high molecular weight, >75% deacetylated)

- Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA, Mw ~100,000)

- 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) as a crosslinker

- Doxorubicin hydrochloride (model chemotherapeutic drug)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) at various pH (7.4, 6.5, 5.0)

Protocol:

- Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve 2% (w/v) chitosan in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution under constant stirring until fully dissolved. Separately, prepare a 4% (w/v) solution of PAA in deionized water.

- Hydrogel Formation: Slowly add the PAA solution to the chitosan solution in a 1:1 volume ratio under vigorous stirring. The mixture will form a polyelectrolyte complex via electrostatic interactions between the ammonium groups of chitosan and the carboxylate groups of PAA.

- Crosslinking: Add EDC (20 mM final concentration) to the mixture to crosslink the carboxylic acid groups of PAA with the amine groups of chitosan, forming stable amide bonds. Stir for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Drug Loading: Add doxorubicin (1 mg/mL final concentration) to the pre-gel solution and mix thoroughly. The drug will be physically encapsulated within the forming hydrogel network.

- Gelation and Purification: Transfer the solution into a mold and allow it to crosslink completely for 24 hours at 4°C. Wash the resulting hydrogel extensively with PBS (pH 7.4) to remove unreacted crosslinker and any surface-bound drug.

Characterization and Release Study:

- Swelling Ratio: Weigh the hydrated gel (Wₛ), lyophilize it, and weigh the dry gel (W𝒹). Calculate the swelling ratio as (Wₛ - W𝒹)/W𝒹. Perform this in PBS at pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0 to demonstrate pH-dependent swelling.

- In Vitro Drug Release: Immerse the loaded hydrogel in PBS at pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 at 37°C under gentle agitation. At predetermined time intervals, withdraw release medium and analyze doxorubicin concentration using UV-Vis spectroscopy at 480 nm. Replenish with fresh buffer to maintain sink conditions. Expect a significantly faster release at the acidic pH due to protonation of amine groups, leading to hydrogel swelling and bond dissociation [28] [29].

4D Printing of a Temperature-Responsive Shape Memory Polymer

Objective: To fabricate a 4D-printed vascular stent that expands at body temperature using a temperature-responsive shape memory polymer.

Materials:

- Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) pellets, a biodegradable polymer with a melting point of ~60°C and a shape memory transition temperature near 40-45°C.

- Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) 3D printer with a high-temperature print head.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Water bath or incubator set to 37°C and 45°C.

Protocol:

- Filament Preparation: Dry PCL pellets thoroughly in a vacuum oven to remove moisture. Use a filament extruder to process the pellets into a uniform 1.75 mm diameter filament for FDM printing.

- CAD Model and "Permanent Shape" Design: Design a 3D model of the fully expanded stent using computer-aided design (CAD) software.

- 3D Printing ("Programming"): Print the stent model using the FDM printer. The printing process involves heating the PCL above its melting point and depositing it layer-by-layer. As it cools and solidifies below its transition temperature, this printed form is considered the permanent shape.

- Deformation to "Temporary Shape": Heat the printed stent to a temperature above its transition temperature (e.g., 45°C) but below its melting point. While hot and soft, mechanically deform it into a compact, temporary shape (e.g., a stretched, narrow-diameter tube). Cool and fix the stent in this temporary shape under constraint.

- Shape Recovery Testing: Immerse the constrained, temporary-shaped stent in a PBS bath at 37°C (simulating body temperature). Release the constraint and record the recovery process using a camera. Quantify the shape recovery ratio (Rᵣ) as Rᵣ = (εₘ - ε(𝓉)) / εₘ × 100%, where εₘ is the strain in the temporary shape and ε(𝓉) is the strain at time 𝓉 [30] [25].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for 4D printing a temperature-responsive vascular stent, illustrating the process from digital design to triggered shape recovery in a physiological environment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Research on Smart Biomaterials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAm) | Thermo-responsive polymer for cell sheets & drug delivery [26]. | LCST ~32°C; can be copolymerized to adjust transition temperature; check biocompatibility of final product. |

| Chitosan | Natural, pH-responsive cationic polysaccharide [25] [27]. | Soluble in acidic solutions; biocompatible and biodegradable; reactivity of amine groups allows for chemical modification. |

| Poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) | Anionic, pH-responsive polymer for hydrogels & composites [28] [25]. | Swells at high pH due to carboxylate group ionization; often used with cationic polymers for complexation. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable, bioactive hydrogel derived from denatured collagen [27]. | Excellent cell adhesion; mechanical and physical properties tunable via degree of methacrylation and crosslinking. |

| Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) | Biodegradable, synthetic polyester for SMPs & 4D printing [30] [25]. | Low melting point (~60°C); shape memory effect; slow degradation rate suitable for long-term implants. |

| Iron Oxide (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles | Magnetic filler for magneto-responsive composites [30]. | Enables remote actuation via magnetic fields; requires homogeneous dispersion in polymer matrix; surface modification may be needed. |

| Pluronic F127 (Poloxamer 407) | Thermo-responsive triblock copolymer for injectable hydrogels [27]. | Forms free-flowing sol at low temps, gel at body temp; reverse thermal gelling; can be used for drug encapsulation. |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) | Zero-length crosslinker for carboxyl and amine groups [27]. | Facilitates formation of amide bonds; used for stabilizing hydrogels; avoids incorporation of large crosslinker molecules. |

Quantitative Data and Performance Metrics

The efficacy of smart biomaterials is quantified through a series of standardized metrics that evaluate their responsive behavior, mechanical properties, and biological performance.

Table 3: Key Performance Metrics for Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials

| Performance Metric | Definition & Formula | Significance in Tissue Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Shape Memory Properties | ||

| Shape Fixity Ratio (Rf) | Rf = εu / εm × 100% εu: fixed strain after cooling & load removal ε_m: maximum strain under load [30] | Measures ability to be fixed in a temporary shape. Critical for minimally invasive delivery of implants. |

| Shape Recovery Ratio (Rr) | Rr = (εm - εr) / εm × 100% ε_r: residual strain after recovery [30] | Measures ability to recover the original, permanent shape. Ensures device functionality upon implantation. |

| Drug Release Kinetics | ||

| Cumulative Drug Release | % Released = (M𝓉 / M∞) × 100% M𝓉: drug released at time 𝓉 M∞: total loaded drug [28] [29] | Quantifies release profile. A burst release followed by sustained release is often targeted for therapies. |

| Hydrogel Swelling | ||

| Equilibrium Swelling Ratio (ESR) | ESR = (Wₛ - W𝒹) / W𝒹 Wₛ: weight of swollen gel W𝒹: weight of dry gel [27] | Induces water content and porosity. Affects nutrient diffusion, cell infiltration, and release kinetics. |

| Material Cytocompatibility | ||

| Cell Viability (via MTT/XTT assay) | % Viability = (ODsample / ODcontrol) × 100% [31] | Fundamental requirement. Ensures the biomaterial and its degradation products are non-toxic to cells. |

Smart biomaterials responsive to temperature, pH, and magnetic fields are fundamentally altering the landscape of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. By transitioning from static implants to dynamic systems that interact intelligently with their biological environment, these materials enable sophisticated applications such as self-fitting implants, spatially and temporally controlled drug delivery, and tissue scaffolds that provide active mechanical cues. The convergence of these materials with 4D printing technologies is particularly powerful, allowing for the fabrication of complex, patient-specific constructs that evolve over time within the body [30] [25].

Despite the remarkable progress, challenges remain in the clinical translation of these systems. The long-term biocompatibility and degradation profiles of some synthetic smart polymers require further investigation [30] [31]. There is also a need to enhance the precision and sensitivity of the responsive mechanisms to finer physiological changes. Future research directions will likely focus on developing multi-responsive materials that can react to a combination of cues in a logical sequence, much like natural biological processes [26]. Furthermore, the integration of bioinstructive capabilities, such as the presentation of specific cell-adhesive ligands or the controlled release of multiple growth factors, will create truly next-generation biomaterials that not only respond to the body but also actively guide and instruct the regenerative process [32] [31]. As the field matures, the role of smart biomaterials is poised to expand, driving innovations in personalized medicine and advanced therapies for tissue regeneration.

Engineering Tissues: Fabrication Techniques and Target Applications

Within the field of tissue engineering, biomaterials are not merely passive structural elements; they are dynamic frameworks that actively orchestrate tissue repair and regeneration. The scaffold, a foundational component, serves as a three-dimensional (3D) analog of the native extracellular matrix (ECM), providing mechanical support and critical biochemical and biophysical cues that direct cell behavior, including adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation [3]. The fabrication technique employed directly determines the scaffold's architectural features—such as porosity, pore size, interconnectivity, and surface topography—which are key determinants of its regenerative performance [33] [34]. This technical guide examines three pivotal scaffold fabrication methods—electrospinning, gas foaming, and particulate leaching—detailing their methodologies, material considerations, and the characteristics of the resulting constructs, thereby framing their essential role within the broader context of biomaterials research for tissue engineering.

Core Fabrication Techniques and Methodologies

Electrospinning

Electrospinning is a versatile technique for producing fibrous scaffolds with a high surface-to-volume ratio that closely mimics the nanoscale architecture of the native ECM [34]. The process involves applying a high voltage to a polymer solution, which creates a charged jet that is drawn toward a grounded collector. As the jet travels, the solvent evaporates, depositing solid, sub-micron to nanoscale fibers that accumulate into a non-woven mat.

- Standard Workflow and Limitations: A conventional setup uses a solid, stationary collector, which often results in densely packed fibers with small pore sizes, typically less than 10 µm [34]. While excellent for cell attachment on the surface, this dense architecture significantly hinders cell infiltration and 3D tissue ingrowth, limiting its application to mostly two-dimensional (2D) cell culture models [34].

- Advanced Modifications to Enhance Cell Infiltration: To overcome these limitations, several modified electrospinning techniques have been developed, as summarized in Table 1.