Cultivating Adaptive Expertise in Biomedical Engineering Education: Strategies for Navigating Complex Healthcare Challenges

This article explores the critical role of adaptive expertise in preparing biomedical engineers and drug development professionals for the unpredictable and rapidly evolving healthcare landscape.

Cultivating Adaptive Expertise in Biomedical Engineering Education: Strategies for Navigating Complex Healthcare Challenges

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of adaptive expertise in preparing biomedical engineers and drug development professionals for the unpredictable and rapidly evolving healthcare landscape. Moving beyond routine problem-solving, adaptive expertise enables professionals to innovate and apply knowledge effectively in novel situations. We examine the foundational theory distinguishing adaptive from routine expertise, present effective educational methodologies including transdisciplinary and experiential learning, address implementation challenges, and review validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and practical applications, this work provides a comprehensive guide for educators and institutions aiming to foster the next generation of agile and innovative biomedical experts capable of addressing complex healthcare challenges from device development to therapeutic innovation.

Beyond Routine Expertise: Defining the Conceptual Framework for Adaptive Learning in Biomedicine

In the demanding and rapidly evolving field of biomedical engineering, the nature of expertise itself is a critical factor in innovation and problem-solving. Traditionally, expertise has been associated with high efficiency and accuracy in performing well-practiced tasks. However, a more nuanced understanding distinguishes between routine expertise and adaptive expertise, two fundamentally different approaches to professional challenges [1]. Routine expertise enables professionals to execute established procedures with speed and accuracy, making it essential for standardized laboratory protocols and quality control processes. In contrast, adaptive expertise empowers individuals to respond effectively to novel situations, devise innovative solutions, and apply their knowledge in unprecedented circumstances [1]. For biomedical engineers working at the intersection of biology, medicine, and engineering, where unexpected challenges in drug development or medical device design are common, cultivating adaptive expertise is increasingly recognized as essential for navigating the field's inherent complexities and driving forward translational research.

Theoretical Framework: The Pillars of Adaptive Expertise

The concept of adaptive expertise was first formally introduced by Hatano and Inagaki, who conceptualized it as existing on a continuum with routine expertise at the opposite pole [1]. While both types of expertise are founded on a deep knowledge base within a specific domain, they differ markedly in the structure of that knowledge and the approaches taken to problem-solving.

Foundational Characteristics

- Efficiency and Innovation: Adaptive expertise can be understood as the optimal balance between two dimensions: efficiency, the ability to fluently apply domain knowledge to familiar problems, and innovation, the capacity to devise solutions for new scenarios where no precedents exist [1]. This balance creates what has been termed the "optimal adaptability corridor" [1].

- Anchored Adaptability: Effective adaptiveness does not mean abandoning structure. It rests on a backbone of well-practiced, efficient routines for core tasks, which frees up the cognitive capacity necessary to notice subtle cues, interpret complex situations, and make appropriate adjustments. This has been powerfully described as "anchored adaptability"—where solid routines provide the anchor that enables meaningful flexibility [2].

- Knowledge Organization: A key differentiator between adaptive and routine experts lies not necessarily in the amount of knowledge they possess, but in its organization [2] [1]. Adaptive experts organize their knowledge around deep functional principles rather than just surface-level procedures. This enables them to recognize how and when to apply their knowledge in novel situations, facilitating what is known as analogical reasoning [1].

Core Dimensions and Cognitive Underpinnings

Three principal dimensions are widely used to describe and measure adaptive expertise: domain-specific skills, metacognitive skills, and innovative skills [1]. The interplay between these dimensions is supported by specific cognitive processes.

Table: Core Dimensions of Adaptive Expertise

| Dimension | Description | Manifestation in Biomedical Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Domain-Specific Skills | Declarative ("knowing that"), procedural ("knowing how"), and conditional ("knowing when and where") knowledge [1]. | Understanding not just how to operate a bioreactor, but the biochemical principles governing its function and when to modify parameters. |

| Metacognitive Skills | "Thinking about thinking"; the ability to self-assess one's knowledge, identify gaps, and monitor problem-solving strategies [1]. | A researcher evaluating whether their current statistical knowledge is adequate to analyze a novel, complex dataset. |

| Innovative Skills | The ability to transcend established routines, reconceptualize problems, and develop novel methodologies [1]. | Designing a new drug delivery scaffold that bypasses limitations of existing materials. |

The development and application of these dimensions are influenced by cognitive load theory. Our working memory, where conscious information processing occurs, has severe limitations in capacity [3] [4]. Adaptive experts, through extensive practice and deep understanding, consolidate knowledge into schemas stored in long-term memory. These schemas can be retrieved and applied with minimal cognitive effort, freeing up working memory capacity to handle the novel aspects of a problem [4]. This efficient management of intrinsic cognitive load (the inherent difficulty of the material), reduction of extraneous cognitive load (load imposed by poor presentation or distractions), and optimization of germane cognitive load (load devoted to schema formation) is a hallmark of adaptive expertise [3].

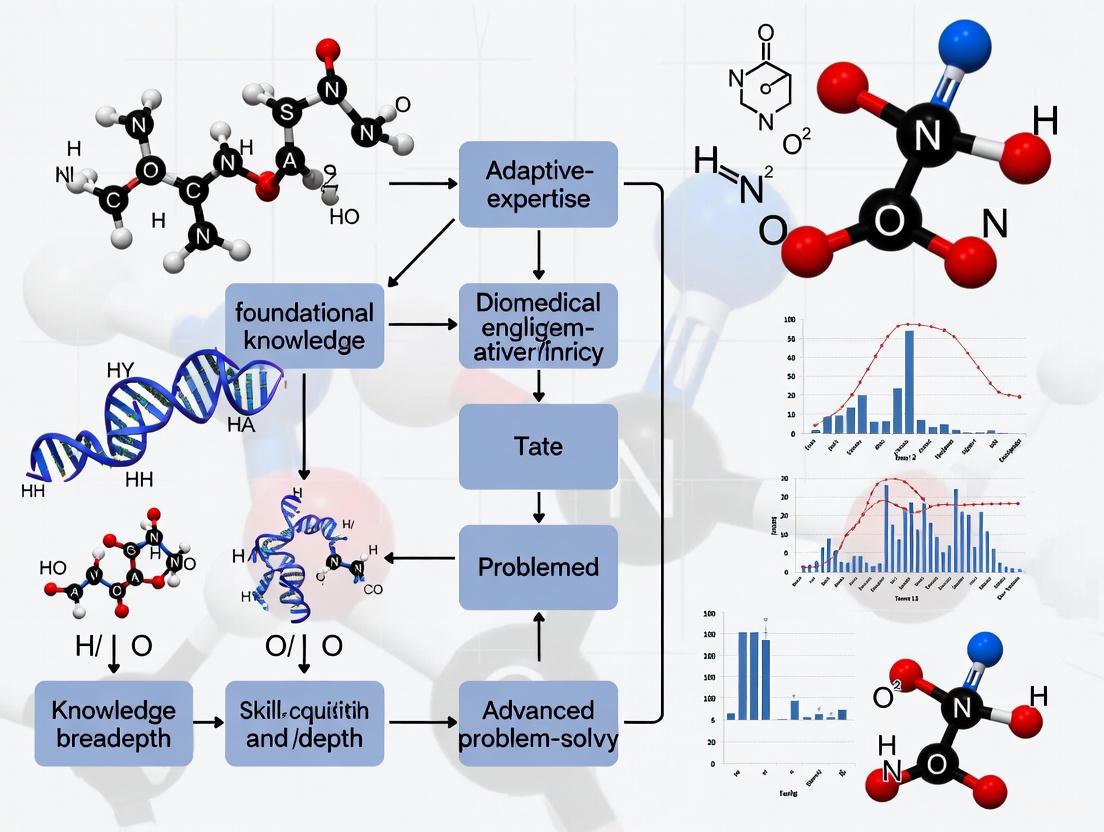

Diagram 1: Cognitive architecture of adaptive expertise, showing how efficient schemas free up working memory for innovation.

Quantitative Assessment and Research Findings

Measuring adaptive expertise requires robust methodological approaches. A common method involves the use of self-reported assessment tools, like the one developed by Carbonell et al. (2016), which probe the different dimensions of the construct [1].

Key Experimental Protocol: Survey-Based Assessment

A recent descriptive, cross-sectional study provides a clear protocol for investigating adaptive expertise among health professions educators (HPEs), a group analogous to biomedical engineering educators in their complex, knowledge-rich environment [1].

- Objective: To investigate how the adaptive expertise of HPEs influenced perceived work performance during the non-standard situation of the COVID-19 pandemic and to examine relationships between adaptive expertise and academic ranking/work experience.

- Population: The study sampled HPEs (lecturers to full professors) from a university.

- Tool: A self-reported survey tool based on the adaptive expertise framework by Carbonell et al. (2016) was used. Participants also answered questions about their perception of work performance, amount of work done, and teaching quality.

- Analysis: The researchers used statistical methods like the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity to ensure sample adequacy. They then analyzed scores for correlations with other variables like academic rank and perceived performance.

Quantitative Results and Correlations

The study yielded insightful quantitative results, summarized in the table below [1].

Table: Correlates of Adaptive Expertise in a Study of Health Professions Educators

| Variable | Correlation with Adaptive Expertise Score | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Work Performance | Positive Correlation (r = 0.41) | p < 0.05 |

| Academic Ranking | Positive Correlation (r = 0.42) | p < 0.05 |

| Work Experience | No Significant Correlation | Not Significant |

| Age of Educator | No Significant Correlation | Not Significant |

The average adaptive expertise score on a 5-point scale was 4.18 ± 0.57, indicating a generally high self-assessment. The findings were particularly revealing: the positive correlation with work performance underscores the practical impact of adaptive expertise, while the correlation with academic rank suggests it is a form of 'mastery' recognized in career advancement. Most importantly, the lack of correlation with age and experience indicates that adaptive expertise is not automatically acquired with seniority but must be deliberately developed [1].

A Framework for Cultivating Adaptive Expertise in Education

Based on the theoretical and empirical evidence, a coherent framework for developing adaptive expertise can be proposed, particularly relevant for biomedical engineering education. This framework posits that adaptive expertise is underpinned by four interconnected facets: the ability to Understand, Do, Decide, and Improve [2].

Diagram 2: Four-facet framework for developing adaptive expertise, illustrating core interconnected capacities.

- Understand: This involves building conceptual knowledge organized around core principles and problems of the field (e.g., "Ensure biocompatibility," "Optimize drug release kinetics") rather than as a rigid list of techniques. This organization makes knowledge more accessible and applicable in new situations [2].

- Do: Tactical knowledge must be supported by technical capability. Learners need a repertoire of techniques that they can practice to a level of high efficiency, freeing cognitive resources for adaptation. As stated in one source, "What is tactically desirable must be technically possible" [2].

- Decide: This facet is driven by situation-sensitive mental models—deeply understood representations of how a system behaves under different conditions. These models allow experts to notice critical cues, interpret their significance, predict potential outcomes, and decide on the best course of action [2].

- Improve: The final facet is an adaptive mindset, characterized by cognitive flexibility and the pursuit of the "best thing" rather than just a "best fit." This involves viewing one's role as requiring continuous improvement, holding problem framings lightly, forming multiple hypotheses, and being prepared to reformulate approaches based on evidence [2].

Research Reagent Solutions: Tools for Investigating Expertise

Studying adaptive expertise in the context of biomedical engineering education requires a toolkit of methodological "reagents." The following table details key tools and their functions based on the cited research.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Adaptive Expertise

| Research Tool / Concept | Function in Investigation |

|---|---|

| Self-Report Assessment (e.g., Carbonell et al. tool) | Quantifies an individual's self-perceived level of adaptive expertise across its core dimensions (domain-specific, metacognitive, innovative skills) [1]. |

| Work Performance Metrics | Provides a correlative measure to validate the impact of adaptive expertise on tangible outcomes like teaching quality, research output, or project success [1]. |

| Cognitive Load Assessment | Measures the intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads experienced by learners during tasks, indicating efficiency of knowledge structure and problem-solving approach [3] [4]. |

| Problem-Solving Protocols (Think-Aloud) | Uncovers the underlying mental models and decision-making processes of individuals when faced with novel problems, distinguishing adaptive from routine approaches [1]. |

| Analysis of Work Products | Evaluates the creativity, efficiency, and appropriateness of solutions generated by individuals or teams in response to standard and novel challenge problems. |

Implications for Biomedical Engineering Education and Research

The distinction between adaptive and routine expertise has profound implications for how biomedical engineers are trained and how research teams are structured and developed. For education, moving beyond a curriculum that primarily transmits static knowledge and procedural skills is necessary. Instructional design should aim to reduce extraneous cognitive load while challenging students to build deep conceptual understanding and flexible mental models [4]. This can be achieved through pedagogical approaches like problem-based learning with variable contexts, analyzing complex case studies, and engaging in deliberate reflection on both successful and unsuccessful problem-solving attempts.

For the professional development of researchers and drug development professionals, the findings suggest that organizations should invest in creating "Situation Sensitive" environments [2]. These environments focus on building a common understanding of first principles, provide coaching and rehearsal to build efficient routines, and frame professional development as continuous, contextual problem-solving rather than the simple application of "best practices." This approach, combined with an awareness of the cognitive principles that underpin expertise, can foster the adaptive capacity necessary to overcome the unprecedented challenges in biomedical engineering and therapeutic development.

The field of biomedical engineering (BME) is experiencing unprecedented transformation driven by technological advancements, increasingly complex human health challenges, and the globalization of the workforce [5]. This evolution demands a fundamental shift in the competencies required of BME professionals, moving beyond traditional technical expertise toward adaptive skills that enable flexibility, innovation, and effective problem-solving in novel situations. The theoretical framework of adaptive expertise provides a crucial lens for understanding how biomedical engineers can navigate this rapidly changing landscape, developing the capacity to apply knowledge flexibly and generate innovative solutions when faced with unusual circumstances or unprecedented challenges [6] [1].

Within health professions education research, adaptive expertise is increasingly recognized as essential for professionals who must solve novel problems and handle ambiguous, complex medical situations [6]. This perspective applies equally to biomedical engineering, where graduates must confront evolving health-related challenges that demand both specialized knowledge and the ability to rapidly acquire additional skills as needed. This whitepaper examines the critical need for adaptive skills in biomedical engineering through analyzing industry demands, educational challenges, and evidence-based frameworks for cultivating adaptive expertise.

Theoretical Framework: Understanding Adaptive Expertise

Adaptive expertise was first conceptualized by Hatano and Inagaki (1986) as a contrast to routine expertise [1] [7]. While routine expertise represents the knowledge and skills that enable efficiency in familiar situations, adaptive expertise encompasses the capability to apply flexible problem-solving approaches and generate novel solutions when unusual circumstances occur [6]. This conceptual distinction is particularly relevant for biomedical engineering, where professionals must balance efficient execution of established procedures with innovation in developing new technologies and approaches.

Dimensions of Adaptive Expertise

Research has identified several critical dimensions that characterize adaptive expertise and distinguish it from routine expertise:

- Domain-specific knowledge: Adaptive experts possess deep conceptual understanding that is organized, abstracted, and consolidated independently of situational contexts, enabling application across various scenarios [1]

- Metacognitive skills: The ability to "think about thinking" allows adaptive experts to assess their knowledge, identify gaps, and strategically apply knowledge in unfamiliar contexts [1]

- Innovation capabilities: Adaptive experts transcend established routines to develop novel solutions, balancing efficiency with creative problem-solving [1]

- Cognitive flexibility: This enables professionals to approach problems from multiple perspectives and adapt strategies as challenges evolve [7]

In healthcare-related fields, adaptive performance is increasingly understood as the visible outcome of adaptive expertise, triggered by contextual changes in tasks or environments [6]. This performance dimension is particularly relevant for biomedical engineers working at the intersection of technology, biology, and medicine, where contextual changes are constant.

Drivers Demanding Adaptive Skills in Biomedical Engineering

Technological Acceleration and Disruption

Biomedical engineering is being transformed by breakthrough technologies including AI-driven protein folding prediction, miRNA-based therapies, mRNA vaccines, CRISPR gene-editing, digital PCR, nanopore sequencing, and single-cell analysis technologies [8]. These innovations emerge at a pace that traditional curricula struggle to match, creating a conspicuous gap between fundamental principles taught in programs and the advanced technologies driving the field forward [8]. This technological volatility requires biomedical engineers to continually adapt to new tools, methodologies, and conceptual frameworks throughout their careers.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning into biomedical engineering practice exemplifies this trend. These technologies are changing how engineering problems are solved across domains including medical imaging, drug discovery, and diagnostic tool development [5]. As noted in industry perspectives from recent Biomedical Engineering Education Summits, critical thinking when analyzing data and adapting to new tools has become increasingly essential, particularly in light of AI advancements and the use of large datasets in BME industry [5].

Increasing Complexity of Health Challenges

Biomedical engineers now address health challenges of unprecedented complexity, often involving interconnected biological systems, multi-scale phenomena, and diverse patient populations. An aging global population, consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, and novel treatment modalities have collectively created urgent needs for more sophisticated diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions [8]. These complex challenges resist routine solutions and demand adaptive approaches that integrate knowledge across disciplines and stakeholder perspectives.

The COVID-19 pandemic particularly highlighted the need for adaptive expertise, as professionals across healthcare and related fields were forced to rapidly develop creative, alternative modes of operation when standard practices were disrupted [1]. This disruption extended to biomedical engineering education and practice, requiring rapid adaptation to new constraints and requirements.

Interdisciplinary Work Environments

Biomedical engineering is inherently interdisciplinary, integrating principles from traditional engineering, biological sciences, and medicine [8]. This interdisciplinary nature has intensified as health challenges increasingly require collaboration between specialists from diverse fields. Industry surveys reveal that professional skills including communication, collaboration, and teamwork have grown in importance for BME graduates, with employers emphasizing their critical role in enabling effective work in cross-disciplinary contexts [5].

Table 1: Evolution of Industry Skill Priorities for BME Graduates (2019-2024)

| Skill Category | 2019 Ranking | 2024 Ranking | Significance of Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Skills | 2nd (Interpersonal)5th (Writing)6th (Technical Presentation) | 1st | Increased emphasis on communicating technical work to diverse audiences |

| Problem-solving | 1st | 3rd | Shift from top priority to still important but secondary to professional skills |

| Teamwork/Collaboration | 4th | 2nd | Recognition of essential role in interdisciplinary work environments |

| Programming/Data Science | Not in top rankings | 4th | Emerging importance due to AI and large dataset utilization |

Measuring Adaptive Expertise in Biomedical Contexts

Current Measurement Instruments and Methodologies

A scoping review of measurement instruments for adaptive expertise and adaptive performance in healthcare contexts reveals a growing but limited set of assessment tools [6]. The review identified 19 measurement instruments across 17 articles, only three of which were specifically developed for the healthcare domain. These instruments were categorized into six types, with a noted dominance of self-evaluation and job requirement instruments, while other methods such as design scenarios, mixed-methods instruments, and collegial verbalization remain underrepresented [6].

The instruments vary significantly in their conceptualization, operationalization, and quality of validity and reliability evidence. This measurement challenge is particularly relevant for biomedical engineering education research, as it highlights the need for domain-specific instruments with strong psychometric properties [6].

Relationship Between Adaptive Expertise and Professional Outcomes

Research conducted with health professions educators during the COVID-19 pandemic provides empirical evidence linking adaptive expertise to professional effectiveness. A study of 40 health professions educators found statistically significant correlations between scores of adaptive expertise and both perceived work performance (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) and academic ranking (r = 0.42, p < 0.05) [1]. Interestingly, adaptive expertise scores were not associated with work experience or age, suggesting that adaptive expertise is not automatically acquired with seniority but must be deliberately developed [1].

Table 2: Adaptive Expertise Measurement in Health Professions Education

| Study Aspect | Findings | Implications for BME |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 40 HPEs from University of Twente | Limited generalizability but suggestive for related fields |

| Average AE Score | 4.18 ± 0.57 on 1-5 scale | Establishes baseline for comparison |

| Key Dimensions | Domain and innovative skills as principal distinct dimensions | Highlights areas for targeted development |

| Correlation with Experience | No significant relationship | Challenges assumption that expertise develops automatically with time |

| Correlation with Performance | Significant positive relationship (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) | Supports investment in adaptive skills development |

Educational Frameworks for Developing Adaptive Expertise

The NICE Strategy for Biomedical Engineering Education

The NICE strategy represents an integrated approach to addressing biomedical engineering education challenges through four interconnected components [8]:

New Frontier: This component focuses on exposing students to cutting-edge advancements through recent research articles and artificial intelligence tools such as DeepSeek, ChatGPT, and Kimi to assist with literature search, summarization, and concept clarification [8].

Integrity: Using case studies of both successful scientists and fraudulent cases (e.g., Theranos), students develop ethical reasoning and understand the implications of their work on patient health and society [8].

Critical and Creative Thinking: Through analysis of creative ideas and generation of novel solutions, students develop the cognitive flexibility essential for adaptive expertise. Activities include peer review exercises and case-based discussions of real-world biomedical engineering challenges [8].

Engagement: Involving clinical doctors and industry professionals in teaching provides students with practical context and exposes them to real-world constraints and requirements. This situated learning approach helps develop the conditional knowledge ("knowing when and where") that characterizes adaptive expertise [8].

Implementing Adaptive Expertise Development

Research suggests that adaptive expertise develops through specific types of learning experiences and environments. Key factors that influence its development include [7]:

- Task variety and complexity: Exposure to diverse problems with varying levels of complexity

- Metacognitive prompting: Activities that encourage reflection on problem-solving strategies

- Feedback quality: Timely, specific feedback focused on deeper understanding

- Learning climate: Environments that tolerate mistakes and encourage experimentation

For biomedical engineering education, this implies a shift from traditional lecture-based approaches to experiential, problem-based learning that presents students with novel, ill-structured challenges resembling real-world biomedical engineering contexts.

Research Reagents and Methodological Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Adaptive Expertise Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Carbonell et al. Adaptive Expertise Instrument | Self-reported measure of adaptive expertise dimensions | Quantifying adaptive expertise levels in educational interventions |

| Domain-specific knowledge assessments | Measuring depth and organization of technical knowledge | Evaluating conceptual understanding versus rote memorization |

| Think-aloud protocols | Capturing metacognitive processes during problem-solving | Studying differences in problem-solving approaches between routine and adaptive experts |

| Design scenarios | Presenting novel engineering challenges for response analysis | Assessing innovation and flexibility in applied contexts |

| AI-assisted learning tools (ChatGPT, DeepSeek) | Supporting literature review and concept mastery | Developing independent learning skills for navigating rapidly evolving fields |

The critical need for adaptive skills in biomedical engineering stems from fundamental changes in the field itself—its accelerating technological base, increasingly complex problems, and highly interdisciplinary nature. The theoretical framework of adaptive expertise provides valuable insights into how biomedical engineers can be prepared to navigate this evolving landscape, emphasizing the importance of deep conceptual understanding, metacognitive skills, and innovative capabilities alongside technical proficiency.

Educational approaches such as the NICE strategy demonstrate how adaptive expertise can be cultivated through intentional curriculum design that balances technical knowledge with professional skills, ethical reasoning, and real-world engagement. As the field continues to evolve, developing and validating reliable measurement instruments for adaptive expertise will be crucial for advancing educational research and practice in biomedical engineering.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing this adaptive mindset is not merely beneficial but essential for driving innovation and addressing the complex health challenges of our time. The institutions that will lead the future of biomedical engineering are those that recognize this imperative and deliberately create environments where adaptive expertise can flourish.

This whitepaper examines the three core dimensions of adaptive expertise development in biomedical engineering education: domain-specific knowledge, metacognition, and innovation capacity. Through analysis of contemporary educational frameworks and empirical studies, we demonstrate how the strategic integration of these dimensions prepares biomedical engineering professionals for complex challenges in drug development and medical technology innovation. The NICE (New frontier, Integrity, Critical and creative thinking, Engagement) strategy provides a foundational model for cultivating these competencies, with evidence showing significant improvements in student outcomes across multiple institutions. We present quantitative data from implementation studies, detailed experimental protocols for educational interventions, and visualization of key conceptual relationships to guide researchers and educators in developing more effective training paradigms for the biomedical workforce.

Biomedical engineering stands at the intersection of rapid technological advancement and pressing healthcare needs, distinguished from traditional disciplines by its highly interdisciplinary nature and focus on practical solutions translatable to clinical applications [9]. The convergence of an aging global population, post-pandemic challenges, and novel treatment modalities has created unprecedented demand for sophisticated diagnostic tools and therapeutic technologies [9]. This landscape requires professionals who possess not only technical knowledge but also the adaptive expertise to apply this knowledge flexibly in novel situations and evolving contexts.

Adaptive expertise refers to the ability to use knowledge and experience to learn in unanticipated situations, contrasting with routine expertise that applies knowledge appropriately to solve routine problems [10]. In biomedical engineering, this adaptability is crucial because the regulatory environment and knowledge base are likely to change significantly over the course of a professional's career [10]. Research indicates that adaptive expertise can be systematically cultivated through educational approaches that simultaneously develop domain-specific knowledge, metacognitive skills, and innovation capacities [11].

Domain-Specific Knowledge: Building the Foundational Framework

Domain-specific knowledge in biomedical engineering encompasses both fundamental principles and awareness of cutting-edge advancements. Current biomedical engineering curricula often emphasize foundational principles while lacking coverage of emerging technologies, creating a significant curriculum gap [9]. This gap is particularly problematic given recent field revolutions including AI-driven protein folding prediction, miRNA-based therapies, mRNA vaccines, CRISPR gene-editing, digital PCR, nanopore sequencing, and single-cell analysis technologies [9].

The "New Frontier" Approach to Domain Knowledge

The NICE educational strategy addresses this challenge through its "New Frontier" component, which immerses students in recent research literature and emerging technologies [9]. In implementation, students are required to read research articles published within the past two years, summarize related articles, and present findings orally. Artificial intelligence tools including DeepSeek, ChatGPT, and Kimi are integrated to assist with literature search, summarization, and concept clarification [9].

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of New Frontier Implementation (3-Year Period)

| Metric | Pre-Implementation | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student Satisfaction | 72% | 85% | 88% | 91% |

| Industry Readiness Score | 68% | 79% | 82% | 86% |

| Technical Knowledge Retention | 70% | 81% | 85% | 87% |

Experimental Protocol: Current Literature Integration

Objective: Enhance students' familiarity with emerging technologies and research methodologies in biomedical engineering.

Materials:

- Access to scientific databases (PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Web of Science)

- AI-based research tools (DeepSeek, ChatGPT, Kimi)

- Structured presentation templates

- Peer evaluation rubrics

Procedure:

- Students select a recent research article (published within last 24 months) relevant to course topics

- Using AI tools, students identify 4-6 related articles and generate summaries

- Students create critical analyses highlighting methodological strengths/limitations

- Oral presentations (15 minutes) delivered to peer audience

- Peer reviewers evaluate presentations using standardized rubrics

- Instructors provide feedback on technical accuracy and critical analysis depth

Assessment: Pre- and post-tests measuring knowledge of emerging technologies; industry partner evaluations of technical presentations; longitudinal tracking of publication literacy.

Metacognition: The Core of Self-Directed Learning and Professional Growth

Metacognition, often described as "thinking about thinking," involves the regulation of one's cognitive activities in learning processes [12]. It encompasses both knowledge of cognition (knowing about persons, tasks, and strategies) and regulation of cognition (planning, monitoring, controlling, and evaluating activities) [12]. In biomedical engineering education, metacognitive skills enable students to become self-directed learners who can assess task demands, evaluate their knowledge and skills, plan approaches, monitor progress, and adjust strategies as needed [12].

Concept Mapping as a Metacognitive Tool

Concept mapping serves as an effective metacognition tool in biomedical engineering education. Research shows that concept mapping helps students organize knowledge systematically, describe connections between concepts, create visual representations of relationships, verbalize their understanding, and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses [12]. The process involves diagramming mental connections between concepts, which promotes deeper understanding and reveals "muddiest points" where students struggle most.

Table 2: Concept Mapping Implementation Outcomes in Biomedical Engineering Courses

| Parameter | In-Person Instruction (2019) | Online Instruction (2021) |

|---|---|---|

| Completion Rate | 59.30% | 47.67% |

| Performance Improvement (p-value) | > 0.05 (not significant) | > 0.05 (not significant) |

| Student Perception of Usefulness | 78% | 78% |

| Willingness to Apply in Other Courses | 84% | 84% |

| Effect Size | 0.29 | 0.33 |

The MENTOR Framework for Metacognitive Development

The MENTOR (MEtacognition-driveN self-evoluTion framework for uncOvering and mitigating implicit Risks) framework represents an advanced approach to developing metacognitive capabilities, originally developed for LLMs but with applicability to biomedical engineering education [13]. This framework employs metacognitive strategies including perspective-taking (evaluating responses from diverse viewpoints) and consequential thinking (assessing potential real-world impacts) to enhance critical self-assessment [13].

Diagram Title: MENTOR Metacognitive Framework

Experimental Protocol: Concept Mapping Intervention

Objective: Develop metacognitive skills through visual knowledge representation and reflection.

Materials:

- Concept mapping software (CmapTools, MindMeister, or physical materials)

- Structured reflection prompts

- Peer feedback forms

- Metacognitive awareness inventory

Procedure:

- Introduction to concept mapping principles and examples

- Identification of core concepts and relationships for specific biomedical engineering topics

- Individual concept map creation (weeks 8-10 of course)

- Paired explanations and peer feedback sessions

- Revision of concept maps based on feedback

- Completion of structured reflection prompts addressing:

- Knowledge organization strategies

- Connection identification processes

- Challenge recognition in concept relationships

- Self-assessment of understanding

Assessment: Pre- and post-intervention metacognitive awareness inventories; concept map complexity scores; qualitative analysis of reflection responses; longitudinal tracking of problem-solving approaches.

Innovation: Cultivating Creative Capacity in Biomedical Engineering

Innovation in biomedical engineering education requires fostering both critical and creative thinking as complementary processes [9]. Critical thinking provides the analytical framework to evaluate and refine creative ideas, while creative thinking pushes boundaries by generating novel solutions [9]. Traditional educational models often prioritize rote learning and compliance, but a shift toward fostering innovation capacity is necessary to prepare students for the dynamic biomedical landscape.

Engagement with Clinical and Industrial Contexts

The "Engagement" component of the NICE strategy addresses the need for practical innovation experience by actively involving clinical doctors and industry professionals in teaching and student product development projects [9]. This approach bridges the gap between academia and industry, providing students with hands-on experience in identifying unmet clinical needs and translating them into viable product designs.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration Framework

Innovation in biomedical engineering increasingly requires interdisciplinary collaboration between medical experts and engineers. Research indicates that making disciplinary perspectives explicit significantly enhances collaboration effectiveness [14]. A structured framework for analyzing disciplinary perspectives includes examining:

- Epistemic Questions: What constitutes knowledge in the discipline?

- Teleological Questions: What are the primary goals of the discipline?

- Methodological Questions: What methods are valued for knowledge production?

- Ontological Questions: What are the fundamental entities of study?

Diagram Title: Interdisciplinary Innovation Framework

Experimental Protocol: Clinical Product Innovation Project

Objective: Develop innovation skills through authentic product development experiences.

Materials:

- Clinical need identification templates

- Industry mentor guidance protocols

- Prototyping resources (3D printers, simulation software)

- Design review presentation templates

Procedure:

- Student teams (3-5 members) formed with mixed backgrounds

- Clinical immersion sessions to identify unmet needs through:

- Observation of clinical procedures

- Interviews with healthcare providers

- Analysis of workflow inefficiencies

- Ideation sessions to generate potential solutions

- Regular consultation with industry mentors on:

- Technical feasibility

- Regulatory considerations

- Manufacturing constraints

- Business model alignment

- Prototype development and iteration

- Final design reviews with clinical and industry panels

Assessment: Prototype functionality scores; clinical impact potential ratings; innovation novelty evaluations; business viability assessments; longitudinal tracking of patent applications and technology commercialization.

Integration and Assessment: Measuring Development Across Dimensions

The comprehensive development of domain-specific knowledge, metacognition, and innovation capacity requires integrated assessment strategies. Research from Northwestern University's Engineering Education Research Center demonstrates the importance of measuring computational adaptive expertise in design and innovation contexts [11]. Their framework evaluates both efficiency (routine expertise) and innovation (adaptive expertise) across multiple dimensions.

Table 3: Integrated Assessment Framework for Adaptive Expertise Development

| Dimension | Assessment Methods | Performance Indicators | Benchmark Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Knowledge | Pre/post content tests; Literature analysis assignments; Technical presentation evaluations | Accuracy scores; Depth of critical analysis; Knowledge application accuracy | >85% content mastery; Industry-rated presentation competence >4.0/5.0 |

| Metacognition | Concept mapping complexity; Reflection journal quality; Self-regulated learning strategies inventory | Connection diversity; Insight depth; Strategy adaptation frequency | >3.5/5.0 metacognitive awareness; >80% strategy diversification |

| Innovation | Project novelty ratings; Clinical impact potential; Interdisciplinary collaboration effectiveness | Solution originality; Need specificity; Perspective integration quality | >4.0/5.0 innovation rating; >90% interdisciplinary communication competence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical Engineering Education and Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AI Research Assistants (ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Kimi) | Literature search, summarization, and concept clarification | New Frontier implementation; Research methodology development |

| Concept Mapping Software | Visual knowledge representation and connection identification | Metacognitive skill development; Conceptual relationship clarification |

| Interdisciplinary Perspective Framework | Systematic analysis of disciplinary approaches and assumptions | Innovation projects; Cross-functional team collaboration |

| Static-Dynamic Hybrid Rule Pool | Structured guidance with adaptive learning capabilities | Ethical decision-making; Regulatory compliance training |

| Activation Steering Mechanisms | Direct modulation of reasoning processes during task execution | Metacognitive strategy implementation; Complex problem-solving |

| 1-(4-Hydroxy-2-methoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-prenylphenyl) | 1-(4-hydroxy-2-methoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-prenylphenyl)propane | High-purity 1-(4-hydroxy-2-methoxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxy-3-prenylphenyl)propane for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N-Boc-15-aminopentadecanoic acid | N-Boc-15-aminopentadecanoic Acid|RUO | N-Boc-15-aminopentadecanoic acid is a specialty fatty acid derivative for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in chemical synthesis. |

The integration of domain-specific knowledge, metacognition, and innovation represents the cornerstone of adaptive expertise development in biomedical engineering education. The NICE strategy provides a validated framework for simultaneously addressing these dimensions, with empirical evidence demonstrating significant improvements in student outcomes across multiple metrics. The experimental protocols and assessment strategies outlined in this whitepaper offer practical approaches for implementing these educational innovations across diverse institutional contexts.

As biomedical engineering continues to evolve in response to technological advancements and healthcare challenges, the cultivation of adaptive expertise becomes increasingly critical. Educational programs that strategically integrate domain-specific knowledge, metacognitive development, and innovation capacity will best prepare the next generation of biomedical engineers to develop transformative solutions to medicine's most pressing problems. Future research should focus on longitudinal tracking of career outcomes and refinement of assessment methodologies to further validate and enhance these educational approaches.

The Optimal Adaptability Corridor represents a critical framework for expert development in biomedical engineering, describing the dynamic balance between two essential dimensions: efficiency in applying established knowledge to solve routine problems, and innovation in generating novel solutions for unprecedented challenges. This concept, rooted in the adaptive expertise theory first introduced by Hatano and Inagaki, has gained renewed urgency in healthcare education as biomedical engineers face rapidly evolving technologies and complex patient care challenges that demand both procedural fluency and conceptual understanding [1] [15]. Within biomedical engineering education, this framework provides a theoretical foundation for preparing professionals who can not only execute standard protocols with precision but also invent new approaches when confronting novel diagnostic, therapeutic, or rehabilitation challenges.

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a stark demonstration of this imperative, where health professions educators were forced to abruptly shift educational paradigms and develop creative alternatives to traditional training methods [1]. Those with higher adaptive expertise demonstrated significantly better work performance during this disrupted period, highlighting the practical significance of this balance for maintaining educational continuity and quality [1]. Furthermore, research has revealed that adaptive expertise correlates positively with academic ranking but not automatically with age or seniority, suggesting it represents a specialized 'mastery' that must be deliberately cultivated rather than passively acquired through experience [1].

Theoretical Foundations of Adaptive Expertise

Distinguishing Adaptive and Routine Expertise

Adaptive expertise fundamentally differs from routine expertise along critical dimensions of knowledge representation and application. While routine experts demonstrate speed and accuracy in solving problems that fit well-established patterns, they often struggle when faced with novel situations where tasks, methods, or desired outcomes are not previously known [1] [15]. In contrast, adaptive experts respond to novel or unexpected situations more effectively, efficiently, and innovatively by drawing on their conceptual understanding to generate context-appropriate solutions [1].

The key distinction lies in their knowledge representation and cognitive flexibility. Adaptive experts possess knowledge characterized by organization, abstraction, and consolidation that is largely independent of situational contexts (de-contextualization) [1]. This enables them to apply known solutions to new situations more easily through analogical reasoning using their organized knowledge base [1]. Whereas routine expertise focuses primarily on procedural fluency ("knowing how"), adaptive expertise emphasizes both procedural fluency and conceptual understanding ("knowing why"), which permits adaptation to variability in novel and uncertain clinical and research situations [15].

Core Dimensions of Adaptive Expertise

Research has identified several interconnected dimensions that constitute adaptive expertise in practice:

Domain-Specific Skills: Encompassing declarative knowledge (knowing that), procedural knowledge (knowing how), and conditional knowledge (knowing when and where) [1]. Unlike novices, adaptive experts display distinctive knowledge representation in terms of extent, organization, abstraction, and consolidation, which significantly influences their problem-solving capabilities [1].

Innovative Skills: The capacity to transcend established routines and reconsider fundamental ideas, practices, and values to facilitate change [1]. This dimension involves recognizing how previously acquired knowledge can be adapted to novel circumstances, indicating that the knowledge used in innovation processes is both nuanced and complex [1].

Metacognitive Skills: The ability to "think about thinking" – to self-assess one's expertise, knowledge, learning, and problem-solving abilities [1]. While some debate exists about whether metacognitive skills definitively distinguish adaptive from routine expertise, they remain valuable for strategic learning and application of knowledge in unfamiliar contexts [1].

Table 1: Core Dimensions of Adaptive Expertise

| Dimension | Key Characteristics | Role in Adaptive Expertise |

|---|---|---|

| Domain-Specific Skills | Declarative, procedural, and conditional knowledge; de-contextualized knowledge representation | Provides foundational knowledge base organized for flexible application |

| Innovative Skills | Ability to transcend routines, reconceptualize problems, generate novel solutions | Enables creation of new approaches when standard solutions fail |

| Metacognitive Skills | Self-assessment, reflection, recognition of knowledge gaps | Supports continuous learning and strategic application of knowledge |

Measuring Adaptive Expertise in Biomedical Engineering Education

Current Measurement Instruments and Methodologies

A 2025 scoping review of measurement instruments for adaptive expertise and adaptive performance in healthcare professionals revealed 19 distinct instruments, only three of which were specifically developed for the healthcare domain [16]. These instruments can be categorized into six types: self-evaluation instruments, job requirement instruments, knowledge assessment instruments, design scenarios, mixed-methods instruments, and collegial verbalization approaches [16]. The review found a predominance of self-evaluation and job requirement instruments, while other methods such as design scenarios and mixed-methods approaches remain underrepresented despite their potential value [16].

The quality of these instruments varies significantly, with substantial differences in the nature and volume of evidence supporting their validity, reliability, and fairness according to the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing [16]. This measurement challenge is compounded by the relationship between adaptive expertise (the internal knowledge and skills) and adaptive performance (the visible outcome of adaptive expertise), with the latter being triggered by contextual changes in tasks or environments [16].

Quantitative Assessment of Adaptive Expertise

Recent research provides quantitative insights into adaptive expertise development and its correlates. A 2024 study of health professions educators found an average adaptive expertise score of 4.18 ± 0.57 on a 5-point scale, with domain-specific and innovative skills emerging as the principal distinct dimensions [1]. Statistical analysis revealed significant correlations between adaptive expertise scores and both perceived work performance (r = 0.41, p < 0.05) and academic ranking (r = 0.42, p < 0.05) [1]. Notably, no significant associations were found between adaptive expertise scores and work experience or age, reinforcing that adaptive expertise is not automatically acquired with seniority but must be deliberately developed [1].

Table 2: Correlates of Adaptive Expertise in Health Professions Educators

| Variable | Correlation with Adaptive Expertise | Statistical Significance | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Performance | r = 0.41 | p < 0.05 | Higher adaptive expertise associates with better performance in altered environments |

| Academic Ranking | r = 0.42 | p < 0.05 | Professors show higher adaptive expertise than other ranks |

| Work Experience | No significant correlation | p > 0.05 | Expertise not automatically gained through experience alone |

| Age | No significant correlation | p > 0.05 | Not a simple function of age or maturity |

The Optimal Adaptability Corridor: Balancing Efficiency and Innovation

Conceptual Framework and Visual Representation

The Optimal Adaptability Corridor represents the target zone where professionals maintain an effective balance between efficiency and innovation. This balance enables them to apply known solutions efficiently when appropriate while also possessing the conceptual understanding and cognitive flexibility to innovate when facing novel challenges [15]. The corridor metaphor suggests there are boundaries – too much focus on efficiency leads to rigid, routine expertise, while excessive innovation without efficient implementation can lead to inconsistent outcomes.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between key components of adaptive expertise development within the Optimal Adaptability Corridor:

Operationalizing the Balance in Educational Settings

In biomedical engineering education, maintaining the Optimal Adaptability Corridor requires deliberate pedagogical approaches that target both efficiency and innovation dimensions simultaneously. Research indicates that adaptive expertise is best developed through educational experiences that include: (a) explicit integration of clinical signs and symptoms with underlying mechanisms (asking or telling "why"), (b) exposure to meaningful variation (asking "what if" questions), and (c) leveraging struggle and discovery in learning followed by immediate feedback and consolidation [15].

This balanced approach stands in contrast to traditional biomedical engineering education that often overemphasizes efficiency and routine performance. The 5th Biomedical Engineering Educational Summit highlighted the critical need for interdisciplinary knowledge combining principles of engineering, physical sciences, and biological sciences, with an emphasis on teaching techniques that empower students with both technical prowess and critical thinking skills vital to this multifaceted discipline [17].

Implementing Adaptive Expertise Development in Biomedical Engineering Education

Curricular Strategies and Methodologies

Effective development of adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering requires implementing specific evidence-based educational strategies:

Cognitive Integration: Developing deep conceptual knowledge through explicit integration of clinical applications with underlying engineering and biological principles [15]. This approach prepares learners to deal with complexity and continue learning in future practice by understanding not just procedures but why specific approaches work.

Variation Exposure: Systematically introducing meaningful variability in problem-solving contexts through "what if" scenarios that require students to adapt solutions to changing parameters, mirroring real-world biomedical engineering challenges [15].

Struggle and Discovery: Creating controlled challenges that push students beyond routine application of formulas, followed by immediate feedback and consolidation activities [15]. This approach leverages productive failure as a mechanism for developing innovative capacity.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Facilitating teamwork across engineering, clinical, and biological disciplines to emulate the interprofessional networks required in modern healthcare settings [17]. The Biomedical Engineering Educational Summit emphasizes this as essential for addressing complex healthcare challenges.

Experimental Protocols for Developing Adaptive Expertise

Research-validated protocols for cultivating adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering education include:

Protocol 1: Conceptual Explanation Integration Objective: Develop dual understanding of both procedures and underlying mechanisms. Methodology: For each biomedical engineering problem solved, require students to provide both the technical solution and a detailed explanation of why the solution works, referencing fundamental principles from multiple disciplines (engineering, biology, clinical practice). Assessment: Evaluate solutions based on both technical accuracy and depth of conceptual explanation.

Protocol 2: Progressive Variation Training Objective: Build flexibility in applying knowledge to novel situations. Methodology: Present a core biomedical engineering challenge followed by a series of progressively modified scenarios with altered constraints, resources, or objectives. Require students to adapt their initial solution without complete re-learning. Assessment: Measure efficiency in initial solution and innovation in adapted solutions.

Protocol 3: Multi-perspective Problem-Framing Objective: Develop capacity to view challenges from multiple stakeholder perspectives. Methodology: Present complex biomedical problems requiring students to generate and evaluate solutions from at least three different perspectives (e.g., clinical practitioner, patient, medical device regulator, hospital administrator). Assessment: Evaluate breadth of solution options generated and capacity to articulate trade-offs across perspectives.

Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Adaptive Expertise

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Adaptive Expertise Research

| Research Instrument | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Evaluation Scales | Measures self-reported adaptive expertise tendencies | Initial assessment of baseline adaptive capabilities |

| Design Scenario Assessments | Presents novel problems requiring innovative solutions | Evaluation of innovation capacity under constrained conditions |

| Knowledge Assessment Tools | Measures depth and organization of conceptual knowledge | Determining cognitive foundations for adaptive performance |

| Mixed-Methods Instruments | Combines quantitative and qualitative assessment approaches | Comprehensive evaluation of adaptive expertise development |

| Collegial Verbalization Protocols | Records problem-solving discussions with colleagues | Assessment of collaborative adaptation capabilities |

Implications for Biomedical Engineering Competency Frameworks

The integration of adaptive expertise into biomedical engineering education has significant implications for competency frameworks and assessment methodologies. The CanMEDS physician competency framework has recognized the need to better incorporate adaptive expertise, with proposals for the 2025 framework including new competencies specifically addressing the balance between efficient application of known solutions and innovative generation of new approaches during patient care [15].

Similar revisions are needed in biomedical engineering competency standards to explicitly include:

- Capacity to recognize need for flexible knowledge application when facing novelty, uncertainty, and ambiguity in biomedical contexts

- Skill in approaching daily problem-solving as learning opportunities to create new knowledge embedded in practice

- Ability to integrate multiple perspectives from engineering, clinical, and biological disciplines to adaptively respond to biomedical challenges

These competencies align with the broader movement in healthcare education to prepare professionals for future learning, ensuring they can effectively address novel challenges that emerge throughout their careers from rapid technological advancements and evolving healthcare needs [17] [15].

The Optimal Adaptability Corridor provides a powerful framework for reimagining biomedical engineering education to better prepare professionals for the complex, unpredictable challenges of modern healthcare environments. By deliberately balancing efficiency and innovation through evidence-based educational strategies, educators can develop a new generation of biomedical engineers capable of both executing established procedures with precision and generating novel solutions when confronting unprecedented challenges.

Future research should focus on validating biomedical-engineering-specific assessment instruments, developing standardized metrics for tracking progress within the Optimal Adaptability Corridor, and creating targeted interventions for students struggling with either the efficiency or innovation dimensions of adaptive expertise. As biomedical technology continues its rapid advancement, this balanced approach to expertise development will become increasingly essential for ensuring that biomedical engineering education keeps pace with the evolving needs of healthcare delivery and innovation.

In biomedical engineering, adaptive expertise represents a sophisticated model of professional competence that enables experts to respond successfully to novel, complex, and uncertain situations [18] [15]. Unlike routine experts who primarily apply established procedures efficiently, adaptive experts balance efficiency with innovation, allowing them to generate novel solutions when existing knowledge proves insufficient [15] [1]. This balance is particularly critical in biomedical engineering, where professionals routinely confront problems at the interface of engineering, biology, and medicine that lack predetermined solutions [19] [5].

The foundational research of Hatano and Inagaki (1986) established adaptive expertise as a distinct form of competence characterized by the ability to apply knowledge flexibly across varying contexts [18] [1]. In biomedical engineering contexts, this translates to professionals who can not only implement existing protocols and technologies but also reformulate problems, integrate knowledge across disciplinary boundaries, and develop innovative approaches to emerging challenges in medical technology and healthcare [19] [20] [5]. This paper explores the cognitive structures and knowledge representation strategies that enable such adaptive performance, with particular emphasis on implications for biomedical engineering education and practice.

Theoretical Framework: Core Dimensions of Adaptive Expertise

Efficiency-Innovation Balance

Adaptive expertise is characterized by a dynamic balance between efficient application of existing knowledge and innovative generation of new solutions [15]. This balance enables biomedical engineers to execute established procedures with precision while remaining capable of innovating when confronted with novel problems or changing circumstances [21].

Table: Characteristics of Adaptive vs. Routine Expertise in Biomedical Contexts

| Dimension | Adaptive Expertise | Routine Expertise |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Approach | Creates new solutions for novel problems | Applies known solutions to familiar problems |

| Knowledge Structure | Flexible, conceptually organized | Rigid, procedure-based |

| Response to Novelty | Innovates and adapts | Struggles or attempts to force-fit known solutions |

| Error Handling | Treats unexpected outcomes as learning opportunities | Views deviations as failures |

| Biomedical Example | Modifies diagnostic protocol for unusual patient presentation | Strictly adheres to standard protocols regardless of fit |

Conceptual Foundations

Adaptive experts in biomedical engineering demonstrate deep conceptual understanding that enables them to adapt to variability in novel and uncertain situations [15]. This conceptual foundation allows them to understand not just what to do but why certain approaches are appropriate, permitting adaptation when standard solutions prove insufficient [15]. This deep understanding is facilitated by cognitive structures that organize knowledge in ways that emphasize conceptual relationships over surface-level features [1].

Knowledge Representation in Adaptive Expertise

Structural Characteristics of Expert Knowledge

Adaptive experts develop knowledge representations characterized by hierarchical organization, abstract conceptualization, and decontextualization of principles [1]. These structures enable flexible application of knowledge across diverse biomedical contexts:

Hierarchical Organization: Knowledge is organized around fundamental principles rather than surface features, allowing adaptive experts to recognize deep similarities between seemingly dissimilar problems [1].

Abstract Representation: Concepts are represented at theoretical levels that facilitate transfer across contexts, enabling biomedical engineers to apply engineering principles to biological systems despite surface-level differences [1] [20].

Causal Interconnectedness: Knowledge elements are richly interconnected through causal relationships, allowing adaptive experts to mentally simulate outcomes and generate novel solutions [1].

Metacognitive Components

Metacognition—"thinking about thinking"—plays a crucial role in adaptive expertise by enabling professionals to monitor their own understanding, identify knowledge gaps, and strategically deploy cognitive resources [1]. While some debate exists about whether metacognitive skills definitively distinguish adaptive from routine expertise, they undeniably support professionals in recognizing when familiar approaches are insufficient and new learning is required [1].

Experimental Approaches to Studying Knowledge Structures

Methodologies for Investigating Expert Knowledge

Research on adaptive expertise employs diverse methodologies to elucidate how experts structure their understanding:

Table: Experimental Methods for Studying Knowledge Representation

| Methodology | Application | Key Metrics | Biomedical Engineering Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Think-Aloud Protocols | Tracing problem-solving processes | Verbalized reasoning steps, hypothesis generation | Recording experts' thoughts while designing medical devices |

| Concept Mapping | Revealing knowledge organization | Node connections, hierarchical structure, cross-links | Mapping relationships between engineering principles and biological systems |

| Comparative Case Analysis | Contrasting expert-novice differences | Problem framing, solution pathways, innovation | Comparing approaches to diagnostic technology development |

| Longitudinal Assessment | Tracking expertise development | Knowledge fluency, adaptive transfer, innovation frequency | Studying BME students throughout studio-based curriculum |

Protocol: Studio-Based Learning Assessment

The Cornell University BME Department implemented a studio-based pedagogical approach to develop adaptive expertise, using the following assessment protocol [19]:

Data Collection Instruments:

- Studio artifacts (completed worksheets documenting problem-solving processes)

- Post-studio student reflections on their learning experiences

- End-of-semester surveys with Likert-scale and open-ended questions

Analytical Framework:

- Mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative analysis

- Thematic coding of open-ended responses to identify trends

- Performance indicator rubrics to assess problem-solving proficiency

- Analysis of collaborative patterns using Google Slides/Documents platforms

Key Outcome Measures:

- Ability to formulate mathematical equations for biological systems

- Iterative refinement of solutions through repetitive practice

- Collaborative problem-solving behaviors

- Development of engineering identity

This methodology revealed that embedding studio-based learning throughout the engineering curriculum—rather than as standalone courses—offered a transformative approach to developing engaged and adaptable biomedical engineers [19].

Interdisciplinary Integration in Biomedical Contexts

Disciplinary Perspectives Framework

Biomedical engineering inherently requires integration of knowledge across multiple disciplines, creating unique challenges for knowledge representation. Adaptive expertise in this field involves recognizing and navigating different disciplinary perspectives—the distinct ways experts from various fields approach problems based on their training and epistemological frameworks [20].

A framework developed to make these perspectives explicit includes analyzing [20]:

- Epistemological commitments: What counts as knowledge in different disciplines

- Characteristic methods: Preferred approaches to investigation and validation

- Conceptual frameworks: Foundational theories and models

- Success criteria: How solutions are evaluated within each discipline

Knowledge Integration Processes

Adaptive experts employ distinctive processes for integrating knowledge across disciplinary boundaries:

Educational Implications and Development Strategies

Cultivating Adaptive Expertise in BME Education

Research indicates that adaptive expertise does not automatically develop with experience alone but requires deliberate educational approaches [1]. Effective strategies include:

Studio-Based Learning: Embedding iterative problem-solving with immediate feedback throughout the curriculum, not just in capstone courses [19]

Work-Based Learning: Providing experiences with challenging, ill-structured real-world problems in safe learning environments [18]

Cognitive Integration: Explicitly connecting clinical signs and symptoms with underlying engineering and biological mechanisms [15]

Variation Exposure: Presenting problems with meaningful variation to develop flexible application of principles [15]

The NICE Strategy for BME Education

The NICE strategy represents a comprehensive approach to developing adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering education [22]:

- New Frontier: Engaging students with cutting-edge research and emerging technologies using AI tools for literature analysis

- Integrity: Case-based learning examining both successful scientific endeavors and ethical failures like the Theranos case

- Critical and Creative Thinking: Peer review exercises and case discussions requiring analysis from multiple perspectives

- Engagement: Direct involvement with clinical doctors and industry partners in product development projects

This approach aligns with constructivist learning principles and problem-based learning methodologies, creating the variation and challenge necessary for developing adaptive expertise [22].

Research Reagent Solutions: Tools for Investigating Knowledge Structures

Table: Key Methodological Approaches for Studying Knowledge Representation

| Research Approach | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept Mapping Software | Visualizing knowledge structures | Identifying organizational patterns in expert vs. novice knowledge | Requires training for consistent application; analysis can be time-intensive |

| Verbal Protocol Analysis | Capturing real-time problem-solving processes | Studying reasoning patterns during biomedical design tasks | May alter natural thinking processes; complex to code and analyze |

| Eye-Tracking Systems | Identifying information attention patterns | Tracing expert-novice differences in interpreting medical data | Requires specialized equipment; data richness necessitates sophisticated analysis |

| fMRI and Neuroimaging | Revealing neural correlates of expertise | Studying brain activity during innovative problem-solving | High cost limits sample sizes; inferring cognitive processes from activation patterns |

| Longitudinal Assessment Tools | Tracking expertise development over time | Evaluating educational interventions in BME programs | Requires sustained participant engagement; challenging to control confounding variables |

Adaptive expertise in biomedical engineering emerges from distinctive knowledge representation structures that enable professionals to balance efficient application of existing knowledge with innovative generation of new solutions. These cognitive structures are characterized by hierarchical organization, abstract representation, causal interconnectedness, and well-developed metacognitive awareness. The development of such expertise requires educational approaches that systematically foster conceptual understanding alongside procedural fluency, while creating opportunities for interdisciplinary integration and iterative problem-solving with authentic challenges.

Future research should further elucidate the specific mechanisms through which biomedical engineers restructure their knowledge throughout professional development, and how educational experiences can optimally support this process. Particularly as the field confronts increasingly complex challenges at the interface of engineering, biology, and medicine, fostering adaptive expertise becomes essential to preparing biomedical engineers who can not only implement existing solutions but also generate novel approaches to emerging healthcare challenges.

Educational Innovations: Implementing Adaptive Learning Strategies in BME Curricula

Biomedical engineering (BME) sits at the intersection of engineering, biology, and medicine, preparing graduates to tackle urgent healthcare challenges through innovations in medical technologies, diagnostics, and AI-powered tools [23]. The growing demand for more efficient, timely, and safer health services, together with insufficient resources, has created unprecedented pressure on health systems worldwide, generating new opportunities to improve and optimize healthcare services from a transdisciplinary perspective [24]. This approach transcends traditional academic disciplinary boundaries, drawing from diverse fields like biology, engineering, computer science, data analytics, and even social sciences to address multifaceted healthcare challenges [25]. Unlike multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approaches that maintain disciplinary boundaries while collaborating, transdisciplinarity involves transcending these boundaries to create entirely new approaches and frameworks for solving complex problems [25].

This whitepaper frames transdisciplinary education within the broader context of adaptive expertise development in biomedical engineering education research. Adaptive expertise refers to the ability to use knowledge and experience in a domain to learn in unanticipated situations, differing from routine expertise which involves appropriately using knowledge to solve routine problems [10] [26]. This framework is directly applicable in the context of design and innovation given the emphasis on how one develops adaptiveness in learning and how to apply knowledge fluidly when faced with novel, ambiguous situations characteristic of healthcare challenges [26]. The very nature of design requires one to recognize how prior knowledge might apply under new circumstances, making adaptive expertise particularly relevant for biomedical engineers who must navigate rapidly evolving technological landscapes and complex healthcare systems [10].

Theoretical Foundations: Connecting Transdisciplinarity and Adaptive Expertise

The Conceptual Framework

The relationship between transdisciplinary education and adaptive expertise development forms a reinforcing cycle that prepares biomedical engineers for complex, real-world challenges. Transdisciplinary learning experiences, particularly those grounded in experiential learning models, provide the ideal context for developing adaptive expertise by regularly placing students in situations where they must integrate and apply knowledge from diverse domains to novel problems.

Table 1: Core Dimensions of Transdisciplinary Education in BME

| Dimension | Traditional Approach | Transdisciplinary Approach | Adaptive Expertise Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Structure | Siloed disciplines with clear boundaries | Integrated knowledge ecosystems | Promotes cross-boundary thinking and knowledge fluidity |

| Problem-Framing | Well-defined problems within single disciplines | Ill-structured, complex real-world problems | Enhances ability to define problems in novel contexts |

| Solution Pathways | Standardized methods and approaches | Innovative, co-created solutions | Fosters innovative thinking and methodological flexibility |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Limited to disciplinary experts | Active collaboration with clinicians, patients, engineers, biologists | Develops communication skills across diverse perspectives |

| Assessment | Discipline-specific knowledge recall | Ability to integrate and apply knowledge in novel situations | Measures transfer of learning to unfamiliar domains |

This framework is supported by Kolb's experiential learning cycle, which provides a foundation for designing transdisciplinary learning experiences. The cycle consists of four stages: concrete experience (engaging in a hands-on activity), reflective observation (reviewing what happened), abstract conceptualization (drawing conclusions and forming generalizations), and active experimentation (applying learning to new situations) [24]. This iterative process naturally cultivates adaptive expertise by continually challenging students to modify their approaches based on reflection and conceptualization [24] [26].

Visualizing the Transdisciplinary Learning Framework

The following diagram illustrates the continuous cycle of transdisciplinary learning and adaptive expertise development:

Methodological Approaches: Implementing Transdisciplinary Education

Experiential Learning in Healthcare Contexts

A significant implementation of transdisciplinary education involves creating relevant learning experiences for biomedical engineering students to expand their knowledge and skills in improving and optimizing hospital and healthcare processes [24]. In one documented approach, healthcare processes were translated into specific learning experiences using the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) model [24]. This model systematically identified the learning context, new concepts and skills to be developed, stages of the student's learning journey, required resources, and assessment methods.

The learning journey was structured around Kolb's experiential learning cycle in a 16-week elective course on hospital management for last-year biomedical engineering undergraduate students [24]. Students engaged in analyzing and redesigning healthcare operations for improvement and optimization using tools drawn from industrial engineering, which expanded their traditional professional role. The fieldwork occurred in two large hospitals and a university medical service, where students observed relevant healthcare processes, identified problems, and defined improvement and deployment plans [24].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Transdisciplinary Healthcare Optimization Course

| Phase | Duration | Activities | Tools & Methods | Stakeholders Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context Analysis | Weeks 1-3 | Hospital immersion, process mapping, problem identification | Observational studies, stakeholder interviews, value stream mapping | Clinical engineers, physicians, nurses, administrators |