Edge-Enhanced Vision: Advancing Medical Image Analysis with Edge Information-Based Methods

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of edge information-based methods for medical image enhancement, a critical domain for improving diagnostic accuracy and computational analysis.

Edge-Enhanced Vision: Advancing Medical Image Analysis with Edge Information-Based Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of edge information-based methods for medical image enhancement, a critical domain for improving diagnostic accuracy and computational analysis. It establishes the foundational role of edge detection in the broader context of medical image segmentation, contrasting traditional techniques with modern deep learning paradigms. The content details specific methodologies and their clinical applications across diverse imaging modalities, including CT, MRI, and X-ray, addressing key challenges such as noise, computational cost, and boundary ambiguity. A thorough evaluation of performance against other segmentation strategies is presented, alongside a forward-looking analysis of how integrating edge priors with emerging technologies like transformers and diffusion models is shaping the future of robust, interpretable clinical AI tools.

The Fundamental Role of Edge Information in Medical Image Analysis

Medical image segmentation and enhancement are fundamental techniques in computational medical image analysis, aimed at improving the quality of images and extracting clinically meaningful regions. These processes are critical for supporting diagnosis, treatment planning, and drug development. Segmentation involves partitioning an image into distinct regions, such as organs, tissues, or pathological areas, while enhancement focuses on improving visual qualities like contrast and edge sharpness to facilitate interpretation. The integration of edge information has emerged as a powerful paradigm for advancing both tasks, as precise boundary delineation is often a prerequisite for accurate segmentation and clinically useful enhancement. This document provides application notes and experimental protocols for contemporary methods in this field, framed within research on medical image enhancement using edge information-based techniques.

State-of-the-Art Frameworks and Quantitative Analysis

Recent research has produced significant advancements in segmentation and enhancement by leveraging edge information. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of several state-of-the-art methods on various medical image segmentation tasks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Medical Image Segmentation and Enhancement Methods

| Method Name | Core Innovation | Reported Metric(s) & Performance | Dataset(s) Used for Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGBINet [1] | Edge-guided bidirectional iterative network with transformer-based feature fusion. | Remarkable performance advantages; superior edge preservation and complex structure accuracy. | ACDC, ASC, IPFP [1] |

| Enhanced Level Set with PADMM [2] | Novel level set evolution with an improved edge indication function and efficient PADMM optimization. | Average Dice: 0.96; Accuracy: 0.9552; Sensitivity: 0.8854; MAD: 0.0796; Avg. Runtime: 0.90s [2] | Not specified in abstract [2] |

| Topograph [3] | Graph-based framework for strictly topology-preserving segmentation. | State-of-the-art performance; 5x faster loss computation than persistent homology methods. [3] | Binary and multi-class datasets [3] |

| Contrast-Invariant Edge Detection (CIED) [4] | Edge detection using three Most Significant Bit (MSB) planes, independent of contrast changes. | Average Precision: 0.408; Recall: 0.917; F1-score: 0.550. [4] | Custom medical image dataset [4] |

| E2MISeg [5] | Enhancing edge-aware 3D segmentation with multi-level feature aggregation and scale-sensitive loss. | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods; achieves smooth edge segmentation. [5] | MCLID (clinical), three public challenge datasets [5] |

| Deep Learning Reconstruction (DLR) [6] | Combined noise reduction and contrast enhancement for CT. | Significantly improved vessel enhancement and CNR (p<0.001); improved qualitative scores. [6] | Post-neoadjuvant pancreatic cancer CT (114 patients) [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Edge-Guided Bidirectional Iterative Network (EGBINet) for Segmentation

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing EGBINet, designed to address blurred edges in medical images through a cyclic, bidirectional architecture [1].

Network Initialization:

- Configure the encoder (e.g., VGG19) to extract five multi-scale encoded features, denoted as (E^1_i) for (i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) [1].

- Initialize the decoder for progressive feature fusion.

First-Stage Forward Pass:

- Region Feature Decoding: Process the encoded features using a progressive decoding strategy [1].

- Edge Feature Extraction: Fuse local edge information from (E^12) and global positional information from (E^15) using multi-layer convolutional blocks to generate the first-stage edge feature, (D_{edge}^1) [1].

Bidirectional Iterative Optimization:

- Feedback Loop: Feed the decoded regional features and edge features from the first stage back into the encoder [1].

- Iterative Refinement: Allow region and edge feature representations to be reciprocally propagated between the encoder and decoder over multiple iterations. This enables the encoder to dynamically adapt to the decoder's requirements [1].

Feature Fusion with TACM:

- Employ the Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM) to group local edge information and multi-level global regional information.

- Adaptively adjust the weights of these grouped features based on their aggregation quality to significantly improve fusion output [1].

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Loss Function: Use a combination of segmentation loss (e.g., Dice loss) and an edge-aware loss term.

- Validation: Evaluate the model on datasets like ACDC, ASC, and IPFP, focusing on edge preservation and complex structure segmentation accuracy [1].

Protocol 2: Enhanced Level Set Evolution with PADMM Optimization

This protocol details the use of an improved level set method with a novel edge function for efficient and accurate segmentation, particularly effective in noisy and blurred conditions [2].

Image Preprocessing:

- Apply standard filtering (e.g., Gaussian) to reduce noise while preserving edges.

Level Set Formulation:

Energy Minimization with PADMM:

- Formulate the segmentation problem as an energy minimization problem where the energy functional incorporates the novel EIF.

- Apply the Proximal Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (PADMM) to solve the minimization problem. This provides a theoretically sound framework with efficient, closed-form solutions, avoiding the instability of traditional gradient descent and the constraints of the CFL condition [2].

Contour Evolution:

- Iteratively update the level set function (\Phi) based on the solution from the PADMM optimization until convergence, which is typically signaled by minimal change in the contour between iterations [2].

Post-processing and Validation:

- Extract the zero-level set of the final (\Phi) as the segmentation boundary.

- Quantitatively evaluate results using metrics such as Dice coefficient, sensitivity, accuracy, and Mean Absolute Distance (MAD) against ground truth data [2].

Protocol 3: Contrast-Invariant Edge Detection (CIED)

This protocol describes a method for detecting edges that is robust to variations in image contrast, which is a common challenge in medical imaging [4].

Image Preprocessing:

- Apply Gaussian filtering and morphological operations to prepare the input image [4].

Bit-Plane Decomposition:

- Decompose the preprocessed image into its bit planes. Extract the three Most Significant Bit (MSB) planes, which contain the majority of the visually significant information [4].

Binary Edge Detection:

- Independently detect edges within each of the three MSB bit planes. This is performed by analyzing 3x3 pixel blocks within each binary image [4].

Edge Fusion:

- Fuse the edge maps obtained from the three MSB planes into a single, comprehensive edge image [4].

Validation:

- Assess the performance on a dedicated medical image edge detection dataset. Calculate precision, recall, and F1-score to benchmark against other edge detection operators [4].

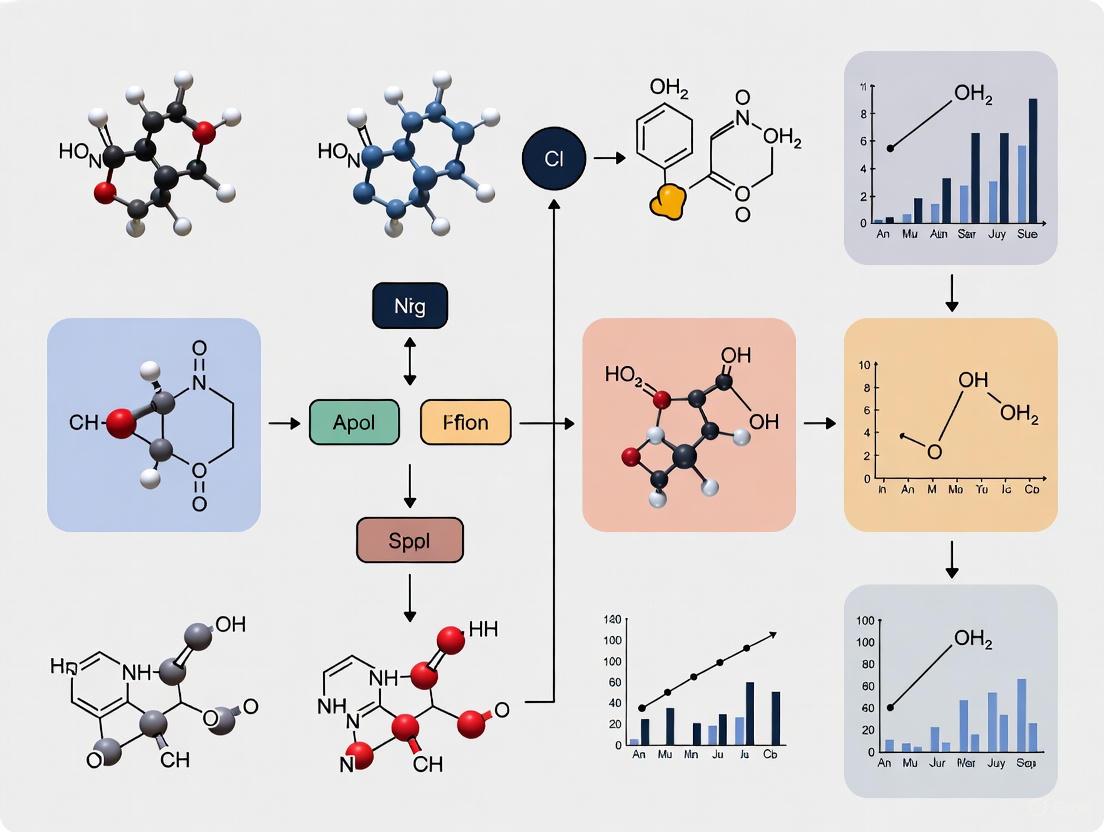

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical workflow of an edge-enhanced segmentation and enhancement system, integrating concepts from the cited frameworks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential computational tools, modules, and datasets used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name / Module | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM) [1] | Neural Network Module | Groups local and multi-level global features, adaptively adjusting their weights to significantly improve feature fusion quality. [1] |

| Proximal Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (PADMM) [2] | Optimization Algorithm | Provides an efficient and theoretically sound framework for solving the level set energy minimization problem, offering closed-form solutions and reducing computation time. [2] |

| Scale-Sensitive (SS) Loss [5] | Loss Function | Dynamically adjusts weights based on segmentation errors, guiding the network to focus on regions with unclear segmentation edges. [5] |

| Most Significant Bit (MSB) Planes [4] | Image Processing Technique | Serves as the basis for contrast-invariant edge detection by using binary bit planes to extract significant edge information, eliminating complex pixel operations. [4] |

| Multi-level Feature Group Aggregation (MFGA) [5] | Neural Network Module | Enhances the accuracy of edge voxel classification in 3D images by leveraging boundary clues between lesion tissue and background. [5] |

| ACDC, ASC, IPFP Datasets [1] | Benchmark Datasets | Standardized public datasets (e.g., Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge) used for training and validating segmentation algorithms, enabling comparative performance analysis. [1] |

| MCLID Dataset [5] | Clinical Dataset | A challenging clinical diagnostic dataset of PET images for Mantle Cell Lymphoma, used to test algorithm robustness against complex, real-world data. [5] |

Edge detection, the process of identifying and localizing sharp discontinuities in an image, transcends its role as a simple image processing technique to become a cornerstone of modern medical image analysis. In clinical practice and research, the precise delineation of anatomical structures and pathological regions is paramount, influencing everything from diagnostic accuracy to treatment planning and therapeutic response monitoring. This document frames the critical importance of edge information within a broader research thesis on medical image enhancement, arguing that methods leveraging edge data are fundamental to advancing the field. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to accurately quantify pathological margins—whether a tumor's invasive front or the precise boundaries of an organ at risk—directly impacts the development and evaluation of novel therapeutics. The following sections detail the technical paradigms, experimental protocols, and practical toolkits that underpin the effective use of edge information in biomedical research.

Technical Approaches and Quantitative Performance

The integration of edge detection into medical image analysis has evolved from using traditional filters to sophisticated deep-learning architectures that explicitly model boundaries. The table below summarizes the performance of several contemporary approaches, highlighting their specific contributions to segmentation accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Edge-Enhanced Medical Image Segmentation Methods

| Method Name | Core Technical Approach | Dataset(s) Used for Validation | Reported Performance Metric(s) | Key Advantage Related to Edges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGBINet [1] | Edge-guided bidirectional iterative network with Transformer-based feature fusion (TACM) | ACDC, ASC, IPFP [1] | Remarkable performance advantages, particularly in edge preservation and complex structure accuracy [1] | Bidirectional flow of edge and region information for iterative boundary optimization [1] |

| E2MISeg [5] | Enhancing Edge-aware Medical Image Segmentation with Multi-level Feature Group Aggregation (MFGA) | Three public challenge datasets & MCLID clinical dataset [5] | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods [5] | Improves edge voxel classification and achieves smooth edge segmentation in boundary ambiguity [5] |

| Contrast-Invariant Edge Detection (CIED) [4] | Fusion of edge information from three Most Significant Bit (MSB) planes | Custom medical image dataset [4] | Average Precision: 0.408, Recall: 0.917, F1-score: 0.550 [4] | Insensitive to changes in image contrast, enhancing robustness [4] |

| U-Net + Sobel Filter [7] | Integration of classic Sobel edge detector with U-Net deep learning model | Chest X-ray images (Lungs, Heart, Clavicles) [7] | Lung Segmentation: Dice 98.88%, Jaccard 97.54% [7] | Enhances structural boundaries before segmentation, reducing artifacts [7] |

| Anatomy-Pathology Exchange (APEx) [8] | Query-based transformer integrating learned anatomical knowledge into pathology segmentation | FDG-PET-CT, Chest X-Ray [8] | Improves pathology segmentation IoU by up to 3.3% [8] | Uses anatomical structures as a prior to identify pathological deviations [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility and rigorous application of edge-enhanced methods, the following sections outline detailed protocols for two distinct, high-impact experimental approaches.

Protocol 1: Integrating Classical Edge Detection with Deep Learning Segmentation

This protocol is adapted from a study that enhanced the segmentation of anatomical structures in chest X-rays by integrating Sobel edge detection with a U-Net model [7]. The workflow is designed to improve boundary delineation in complex anatomical regions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protocol 1

| Item / Reagent | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Chest X-ray Dataset | Images with corresponding ground-truth masks for lungs, heart, and clavicles. |

| Sobel Filter | A discrete differentiation operator computing an approximation of the image gradient to highlight edges. |

| U-Net Architecture | A convolutional neural network with an encoder-decoder structure and skip connections for precise localization. |

| Python Libraries | OpenCV (for Sobel filtering), PyTorch/TensorFlow (for U-Net implementation), Scikit-learn (for metrics). |

| Hardware | GPU-enabled workstation (e.g., NVIDIA Tesla series) for efficient deep learning model training. |

Workflow Diagram: U-Net with Sobel Edge Enhancement

Procedure:

Image Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Obtain a dataset of chest X-ray images in DICOM format alongside their corresponding ground-truth segmentation masks for the lungs, heart, and clavicles [7].

- Resize all images to a uniform dimension (e.g., 256x256 or 512x512 pixels).

- Normalize pixel intensities to a range of [0, 1].

Edge Enhancement:

- Apply the Sobel operator to the preprocessed grayscale image using the

cv2.Sobel()function from the OpenCV library. - The operator uses two 3x3 kernels (for horizontal and vertical derivatives) which are convolved with the original image to approximate the gradient magnitude [7].

- Compute the final edge-enhanced image by calculating the magnitude of the gradients:

G = sqrt(G_x² + G_y²).

- Apply the Sobel operator to the preprocessed grayscale image using the

Model Training and Inference:

- Input Preparation: The original preprocessed image and the Sobel edge-enhanced image are used as inputs. They can be stacked as a two-channel input or fused within the network architecture [7].

- Network Architecture: Implement a standard U-Net architecture. The encoder progressively downsamples the feature maps to capture context, while the decoder upsamples to recover spatial information. Skip connections link encoder and decoder layers to preserve fine details.

- Training: Train the model using a loss function suitable for segmentation, such as Dice Loss or a combination of Dice and Cross-Entropy Loss, to mitigate class imbalance. Use an optimizer like Adam with an initial learning rate of 1e-4.

- Inference: Pass new, unseen X-ray images through the trained model to generate the final multi-class segmentation mask.

Protocol 2: Training an Edge-Guided Bidirectional Iterative Network

This protocol describes the implementation of EGBINet, a sophisticated architecture designed to address blurred edges in medical images through a cyclic, bidirectional flow of information [1].

Workflow Diagram: EGBINet Bidirectional Architecture

Procedure:

Initial Feature Extraction:

- The input image is processed by an encoder (e.g., VGG19) to extract five multi-scale encoded features, denoted as (E_i) where i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 [1].

First-Stage Decoding for Edge and Region Features:

- Edge Feature Extraction: Aggregate local edge information ((E2)) and global positional information ((E5)) to extract edge features. Multi-layer convolutional blocks are used to fuse these scales: (D{edge}^1 = \mathrm{Con}(E2^1, E_5^1)) [1].

- Regional Feature Decoding: A progressive decoding strategy, inspired by UNet, is applied to the multi-level regional features from the encoder. This involves cross-layer fusion: (Di^1 = \mathrm{Con}(Ei^1, D_{i+1}^1)) for i = 1, 2, 3 [1].

Bidirectional Iterative Optimization:

- The decoded edge ((D{edge})) and regional ((Di)) features from the first stage are fed back to the encoder [1].

- This establishes a feedback mechanism from the decoder to the encoder, allowing region and edge feature representations to be reciprocally propagated. This cycle enables the iterative optimization of hierarchical feature representations, allowing the encoder to dynamically refine its features based on the decoder's requirements [1].

Feature Fusion with TACM:

- The Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM) is employed to fuse the local edge information with multi-level global regional information [1].

- TACM groups these features and adaptively adjusts their weights according to the aggregation quality, significantly improving the fusion of edge and regional data for a superior final segmentation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful implementation of the aforementioned protocols relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Edge-Enhanced Medical Image Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Category | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sobel, Scharr Operators | Classical Edge Detector | Highlights structural boundaries by computing image gradients; useful as a pre-processing step or integrated into DL models [7]. |

| U-Net & Variants (e.g., Attention U-Net, U-Net++) | Deep Learning Architecture | Provides a foundational encoder-decoder backbone for semantic segmentation, often enhanced with edge-guided modules [1] [9]. |

| Vision Transformers (ViT) | Deep Learning Architecture | Captures long-range dependencies and global context in images, improving the understanding of anatomical and pathological structures [1] [10]. |

| EGBINet / APEx | Specialized Algorithm | Implements advanced concepts like bidirectional edge-region interaction and anatomy-pathology knowledge exchange for state-of-the-art results [1] [8]. |

| Public Datasets (ACDC, MIMIC-CXR) | Data | Annotated medical image datasets for training and benchmarking segmentation algorithms [1] [7]. |

| Dice Loss / Focal Loss | Loss Function | Manages class imbalance in segmentation tasks, directing network focus to under-segmented regions and boundary voxels [5]. |

Traditional edge-based segmentation methods form a foundational pillar in medical image analysis, enabling the precise delineation of anatomical structures and pathological regions by identifying intensity discontinuities. These techniques—encompassing thresholding, region-growing, and model-based approaches—leverage predefined rules and intensity-based operations to partition images into clinically meaningful regions. Their computational efficiency and interpretability make them particularly valuable in clinical workflows where transparency is paramount. In the broader context of medical image enhancement research, these methods provide critical edge information that can guide and refine subsequent analysis, supporting accurate diagnosis, treatment planning, and quantitative assessment across diverse imaging modalities.

Core Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

Thresholding Techniques

Thresholding operates by classifying pixels based on intensity values relative to a defined threshold, effectively converting grayscale images into binary representations. The core function is defined as:

B(x,y) = 1, if I(x,y) ≥ T B(x,y) = 0, if I(x,y) < T

where I(x,y) represents the pixel intensity at position (x,y), and T is the threshold value [11]. These techniques are categorized into global and local approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Thresholding Techniques

| Technique | Core Principle | Medical Imaging Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Otsu's Method | Maximizes between-class variance | CT, MRI segmentation [12] [11] | Automatically determines optimal threshold; Effective for bimodal histograms | Computational cost increases exponentially with threshold levels [12] |

| Iterative Thresholding | Repeatedly refines threshold based on foreground/background means | General medical image binarization [11] | Simple implementation; Self-adjusting | Sensitive to initial threshold selection |

| Entropy-Based Thresholding | Maximizes information content between segments | Enhancing informational distinctiveness [11] | Effective for complex intensity distributions | Computationally intensive |

| Local Adaptive (Niblack/Sauvola) | Calculates thresholds based on local statistics | Handling uneven illumination [11] | Adapts to local intensity variations; Robust to illumination artifacts | Parameter sensitivity; Potential noise amplification |

Region-Growing Algorithms

Region-growing techniques operate by aggregating pixels with similar properties starting from predefined seed points. These methods are particularly effective for segmenting contiguous anatomical structures with homogeneous intensity characteristics.

Table 2: Region-Growing Approaches in Medical Imaging

| Application Context | Seed Selection Method | Growth Criteria | Reported Performance/Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast CT Segmentation [13] | Along skin outer edge | Voxel intensity ≥ mean seed intensity | Effective for high-contrast boundaries; Fast segmentation |

| Breast Skin Segmentation [13] | Constrained by skin centerline | Combined with active contour models | Reduced false positives; Robust segmentation |

| 3D Skin Segmentation [13] | Manual or automatic seed placement | Intensity/texture similarity | Effective for irregular surfaces; Contiguous region segmentation |

| General Medical Imaging [11] | User-defined or algorithmically determined | Intensity, texture, or statistical similarity | Simple implementation; Preserves connected boundaries |

Model-Based Approaches

Model-based techniques utilize deformable models that evolve to fit image boundaries based on internal constraints and external image forces, making them particularly suitable for anatomical structures with complex shapes.

Table 3: Model-Based Segmentation Techniques

| Method | Core Mechanism | Medical Applications | Strengths | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Contours/Snakes | Energy minimization guided by internal (smoothness) and external (image gradient) forces | Skin surface segmentation in MRI [13] | Captures smooth, continuous boundaries; Handles topology changes | Sensitive to initial placement; May converge to local minima |

| Level-Set Methods | Partial differential equation-driven contour evolution | Complex skin surfaces [13] | Handles complex topological changes; Intrinsic contour representation | Computationally intensive; Parameter sensitivity |

| Atlas-Based Segmentation | Deformation of anatomical templates to patient data | Skin segmentation with prior knowledge [13] | Incorporates anatomical knowledge; Reduces ambiguity | Requires high-quality registration; Limited by anatomical variations |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Otsu's Multilevel Thresholding for Medical Image Segmentation

Objective: To implement an optimized multilevel thresholding approach for segmenting medical images with heterogeneous intensity distributions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Medical image dataset (e.g., MRI, CT scans)

- Computing environment with Python/OpenCV or MATLAB

- Performance evaluation metrics (Dice coefficient, Hausdorff distance)

Methodology:

- Image Preprocessing:

- Convert input image to grayscale if necessary

- Normalize intensity values to standard range (0-255)

- Compute image histogram and probability distribution for each intensity level [12]

Optimization Integration:

- Define Otsu's objective function: Maximize between-class variance σ²_b = w₁w₂(μ₁ - μ₂)² [12]

- Initialize optimization algorithm (e.g., Harris Hawks, Differential Evolution)

- Implement fitness function evaluation for candidate thresholds

Multilevel Thresholding:

- For k thresholds, divide histogram into k+1 classes

- Compute between-class variance for each threshold combination

- Identify optimal thresholds that maximize overall between-class variance

Validation:

- Compare segmentation results with ground truth annotations

- Evaluate computational efficiency relative to exhaustive search

- Assess segmentation quality using domain-specific metrics

Applications: Particularly effective for CT image segmentation where intensity distributions correspond to different tissue types [12].

Protocol 2: Region-Growing for 3D Skin Segmentation

Objective: To extract continuous skin surfaces from volumetric medical imaging data (CT/MRI) for 3D patient modeling.

Materials and Equipment:

- Volumetric medical images (CT/MRI)

- 3D visualization software

- Computation of isovalue for intensity thresholding

Methodology:

- Seed Point Initialization:

- Identify background starting point (typically image corners)

- Verify background classification using automatically computed skin isovalue [13]

Region Propagation:

- Initialize list of pixels to evaluate with neighbors of starting point

- For each candidate pixel, evaluate against isovalue threshold

- Include pixel in segmentation if intensity exceeds isovalue

- Add neighboring pixels to evaluation list

Postprocessing:

- Apply morphological operations to remove noise

- Ensure connectivity of segmented skin surface

- Convert to 3D mesh for visualization and analysis

Applications: Creation of realistic 3D patient models for surgical planning, personalized medicine, and remote monitoring [13].

Protocol 3: Edge-Based Segmentation with Boundary Refinement

Objective: To leverage edge detection operators for precise boundary identification in medical images with subsequent refinement.

Materials and Equipment:

- Medical images with structures of interest

- Edge detection operators (Sobel, Canny)

- Implementation of non-maximum suppression and hysteresis thresholding

Methodology:

- Image Preprocessing:

- Apply Gaussian filtering to reduce noise

- Enhance contrast in boundary regions

Edge Detection:

- Compute gradient magnitude and direction using Sobel operators

- Implement non-maximum suppression to thin edges

- Apply hysteresis thresholding to identify strong, weak, and irrelevant edges [11]

Boundary Completion:

- Connect discontinuous edges using morphological operations

- Validate boundary continuity using anatomical constraints

- Generate final segmentation by region enclosure

Applications: Effective for anatomical structures with clear intensity transitions, such as organ boundaries in CT imaging [11].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification/Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Otsu's Algorithm | Statistical thresholding method | Automatically determines optimal segmentation thresholds by maximizing between-class variance [12] [11] |

| Sobel Operators | Gradient-based edge detector | Identifies intensity discontinuities along horizontal and vertical directions [14] |

| Region-Growing Framework | Pixel aggregation algorithm | Segments contiguous anatomical structures from seed points based on similarity criteria [13] |

| Active Contours Model | Deformable boundary model | Evolves initial contour to fit anatomical boundaries through energy minimization [13] |

| Medical Image Datasets | Clinical imaging data (CT, MRI, PET) | Provides ground truth for algorithm validation and performance benchmarking [5] [12] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Nature-inspired optimizers (Harris Hawks, DE) | Reduces computational cost of multilevel thresholding while maintaining accuracy [12] |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Traditional Edge-Based Segmentation Workflow

Region-Growing for 3D Skin Segmentation

Optimized Otsu's Thresholding Methodology

The Evolution from Classical Operators (e.g., Canny) to Data-Driven Deep Learning

The pursuit of enhanced medical images through the extraction of edge information has undergone a profound transformation, evolving from mathematically defined classical operators to sophisticated, data-driven deep learning models. This evolution is central to advancing diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning in modern healthcare. Classical edge detection methods, such as the Canny, Sobel, and Prewitt operators, rely on fixed convolution kernels to identify intensity gradients, providing a transparent and computationally efficient means of highlighting anatomical boundaries [15]. However, their reliance on handcrafted features often renders them fragile in the presence of noise, low contrast, and the complex textures inherent to medical imaging modalities.

The advent of deep learning has marked a paradigm shift, enabling models to learn hierarchical feature representations directly from vast datasets. These data-driven approaches excel at preserving critical edge details in challenging conditions, fundamentally reshaping segmentation, fusion, and enhancement protocols [16] [17]. Contemporary research now explores a synergistic path, investigating how classical edge priors can be embedded within deep learning architectures to create robust, hybrid frameworks [18]. This article details the experimental protocols and applications underpinning this technological evolution, providing a toolkit for researchers and scientists engaged in medical image analysis.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

The transition from classical to learning-based methods can be quantitatively assessed across key performance metrics. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis based on recent research findings.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Edge Detection and Enhancement Methodologies

| Method Category | Example Techniques | Key Performance Metrics & Results | Primary Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Operators | Canny, Sobel, Prewitt, Roberts [15] | In PD classification, Canny+Hessian filtering degraded most ML model accuracy [19] | Computational efficiency; model interpretability; no training data required | Fragility to noise and low contrast; reliance on handcrafted parameters |

| Fuzzy & Fractional Calculus | Type-1/Type-2 Fuzzy Logic, Grünwald-Letnikov fractional mask [15] [20] | Improved handling of uncertainty; better texture enhancement in grayscale images [20] | Effectively models uncertainty and soft transitions in boundaries | Can introduce halo artifacts; requires manual parameter adjustment |

| Deep Learning (CNN-based) | U-Net, ResNet, EMFusion, MUFusion [18] [21] | Superior accuracy in segmentation and fusion tasks; SSIM, Qabf, VIF [18] | Learns complex, hierarchical features directly from data; high accuracy | High computational demand; requires large, annotated datasets |

| Deep Learning (Transformer-based) | SwinFusion, ECFusion, Cross-Scale Transformer [18] | Captures long-range dependencies; improves mutual information (MI) and structural similarity (SSIM) in fused images [18] | Superior global context modeling; better coordination of structural/functional data | Extremely high computational complexity and memory footprint |

| Hybrid Models (Classical + DL) | ECFusion (Sobel EAM + Transformer) [18] | Clearer edges, higher contrast in MMIF; quantitative improvements in Qabf, Qcv [18] | Leverages strengths of both approaches; explicit edge preservation within data-driven framework | Increased architectural complexity; design and training challenges |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for research, this section outlines detailed protocols for key experiments cited in the literature.

Protocol: Impact of Classical Edge Preprocessing on ML Classification

This protocol is based on the experiment investigating the effect of Canny edge detection on Parkinson's Disease (PD) classification performance [19].

- Objective: To evaluate the impact of Canny edge detection and Hessian filtering preprocessing on the performance, memory footprint, and prediction latency of standard machine learning models.

- Dataset Preparation:

- Source: Handwriting spiral drawings from PD patients and healthy controls.

- Dataset Variants:

- DS₀: The original, normal dataset.

- DS₁:

DS₀processed with Canny edge detection and Hessian filtering. - DS₂: An augmented version of

DS₀. - DS₃: An augmented version of

DS₁.

- Machine Learning Models: Logistic Regression (LR), Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), XGBoost (XGB), Naive Bayes (NB), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), AdaBoost (AdB).

- Evaluation Metrics:

- Primary: Prediction Accuracy.

- Secondary: Model memory footprint (KB), Prediction latency (ms).

- Experimental Procedure:

- Train each of the eight ML models on all four dataset variants (

DS₀,DS₁,DS₂,DS₃). - For each trained model, record the prediction accuracy on a held-out test set.

- Measure the memory size of each saved model.

- Measure the average time required for the model to make a prediction on a single sample.

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., Mann-Whitney U test) using 100 accuracy observations per model to compare performance between datasets (e.g.,

DS₀vs.DS₂).

- Train each of the eight ML models on all four dataset variants (

- Key Analysis:

- Compare accuracy metrics across datasets to determine the effect of edge preprocessing.

- Identify models with stable memory and latency across datasets (e.g., LR, DT, RF) versus those with significant increases (e.g., KNN, SVM, XGBoost) [19].

Protocol: Edge-Enhanced Pre-training for Medical Image Segmentation

This protocol is based on the experiment investigating the effect of edge-enhanced pre-training on foundation models [16].

- Objective: To determine whether pre-training a foundation model on edge-enhanced data improves its segmentation performance across diverse medical imaging modalities.

- Dataset:

- A diverse collection of medical images from multiple modalities (e.g., Dermoscopy, Fundus, Mammography, X-Ray).

- Includes input images and corresponding ground truth segmentation masks.

- Edge Enhancement:

- Method: Kirsch filter.

- Procedure: Apply the Kirsch filter, which uses eight convolution kernels to detect edges in different orientations, to all training images to create an edge-enhanced dataset [16].

- Model Training:

- Step 1 - Pre-training: Create two versions of a foundation model.

- Model A (

fθ): Pre-trained on raw medical images. - Model B (

fθ*): Pre-trained on edge-enhanced medical images.

- Model A (

- Step 2 - Fine-tuning: For each specific medical modality, fine-tune both Model A and Model B on a subset of raw images from that modality.

- Step 1 - Pre-training: Create two versions of a foundation model.

- Evaluation:

- Metrics: Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Normalized Surface Distance (NSD).

- Procedure: Evaluate the fine-tuned models on a held-out test set for each modality.

- Meta-Learning Strategy:

- Extract meta-features (standard deviation and image entropy) from the raw input images.

- Train a classifier to predict, based on these meta-features, whether Model A or Model B will yield better segmentation results for a given image.

- Use this classifier to select the optimal model for inference [16].

Protocol: Multimodal Image Fusion with an Edge-Augmented Module

This protocol is based on the ECFusion framework for multimodal medical image fusion [18].

- Objective: To fuse images from different modalities (e.g., CT-MRI, PET-MRI) into a single image with enhanced edges and high contrast.

- Architecture: The ECFusion framework, comprising an Edge-Augmented Module (EAM), a Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF), and a Decoder.

- Experimental Procedure:

- Input: Register two source images,

I_aandI_b(e.g., a CT and an MRI). - Edge-Augmented Module (EAM):

- Process each input image through the EAM.

- Edge Module: Use Sobel operators

G_xandG_yto extract horizontal and vertical edge maps from the input image. - Feature Extraction: The input image and its edge map are processed through a feature extraction network (e.g., with a channel expansion head and multiple residual blocks) to produce multi-level features

FI_aandFI_b[18].

- Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF):

- Input features

FI_aandFI_bat the same level into the CSTF. - The CSTF uses a Hierarchical Cross-Scale Embedding Layer (HCEL) to capture multi-scale contextual information and fuse the features.

- Input features

- Reconstruction:

- Pass the concatenated, fused features from all levels through the Decoder to generate the final fused image

I_f.

- Pass the concatenated, fused features from all levels through the Decoder to generate the final fused image

- Input: Register two source images,

- Training:

- Mode: Unsupervised.

- Loss Functions: A combination of losses designed to preserve structural information, maintain intensity fidelity, and enhance edge quality.

- Evaluation:

- Quantitative Metrics: Mutual Information (MI), Structural Similarity (Qabf, SSIM), Visual Information Fidelity (VIF),

Q_{cb},Q_{cv}[18]. - Comparison: Compare against state-of-the-art methods like U2Fusion, EMFusion, and SwinFusion.

- Quantitative Metrics: Mutual Information (MI), Structural Similarity (Qabf, SSIM), Visual Information Fidelity (VIF),

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Medical Image Enhancement with Edge Information

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Edge Kernels | Predefined filters for gradient calculation and preliminary boundary identification. | Canny, Sobel, and Kirsch filters for pre-processing or feature extraction [19] [18] [16]. |

| Fuzzy C-Means Clustering | A soft clustering algorithm for tissue classification and unsupervised image segmentation. | Segmenting ambiguous regions in MRI; used in the iMIA platform for soft tissue classification [15]. |

| Lightweight CNN Architectures | Enable deployment of deep learning models on resource-constrained hardware (e.g., edge devices). | MobileNet-v2, ResNet18, EfficientNet-v2 for on-device diagnostic inference [21]. |

| U-Net | A convolutional network architecture with a skip-connection structure for precise image segmentation. | Benchmarking segmentation performance; comparing against ACO for brain boundary extraction [15] [22]. |

| Transformer Modules | Capture long-range, global dependencies in an image through self-attention mechanisms. | Cross-Scale Transformer Fusion Module (CSTF) in ECFusion for global consistency in fused images [18]. |

| Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) | A bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm used for edge detection and pathfinding in images. | An alternative edge extraction method in the iMIA platform; compared against U-Net [15]. |

| Diffusion Models | Generative models that iteratively denoise data, used for training-free universal image enhancement. | UniMIE model for enhancing various medical image modalities without task-specific fine-tuning [23]. |

| Fractional Derivative Masks | Non-integer order differential operators for enhancing texture details while preserving smooth regions. | Grünwald-Letnikov (GL) based masks for texture enhancement in single-channel medical images [20]. |

Workflow and Architectural Diagrams

Edge-Enhanced Pre-training and Segmentation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the two-stage pipeline for investigating edge-enhanced pre-training for medical image segmentation, as described in the experimental protocol.

Hybrid Edge-Deep Learning Fusion Architecture

This diagram details the architecture of a hybrid model (ECFusion) that integrates a classical Sobel operator within a deep learning framework for multimodal image fusion.

Medical imaging is indispensable for modern diagnostics, yet it is fundamentally constrained by intrinsic challenges including noise, low contrast, and profound anatomical variability. These issues complicate automated image analysis, particularly in segmentation and quantification tasks essential for precision medicine. This application note explores how edge information-based methods provide a robust framework for addressing these challenges. We detail specific experimental protocols, present quantitative performance data from state-of-the-art models, and provide a toolkit for researchers to implement these advanced techniques in studies ranging from tumor delineation to organ volumetry.

The fidelity of medical images is compromised by a triad of persistent challenges. Noise, inherent to the acquisition process, can obscure subtle pathological signs. Low contrast between adjacent soft tissues or between healthy and diseased regions makes boundary delineation difficult. Significant anatomical variability across patients and populations challenges the generalization ability of computational models. Edge information, which defines the boundaries of anatomical structures, serves as a critical prior for guiding segmentation networks to produce clinically plausible and accurate results, especially in regions where image contrast is weak or noise levels are high.

The table below summarizes the core challenges and how recent edge-aware methodologies quantitatively address them.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Medical Imaging and Performance of Edge-Enhanced Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Image Analysis | Edge-Enhanced Solution | Reported Performance Metric | Value/Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blurred Edges | Ambiguous organ/lesion boundaries leading to inaccurate segmentation. | EGBINet (Edge Guided Bidirectional Iterative Network) [1] | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | ACDC, ASC, IPFP datasets |

| Boundary Ambiguity | Low edge pixel-level contrast in tumors and organs. | E2MISeg (Enhancing Edge-aware Model) [5] | DSC & Boundary F1 Score | Public challenges & MCLID dataset |

| Speckle Noise | Degrades ultrasound image quality, impacting diagnostic accuracy. | Advanced Despeckling Filters & Neural Networks [24] | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Improvement | Various ultrasound modalities |

| Anatomic Variability | Model failure on structures with large shape/size variations. | TotalSegmentator MRI (Sequence-agnostic model) [25] | Dice Score | 80 diverse anatomic structures |

| Low Contrast | Difficulty in segmenting small vessels and specific organs. | Scale-Sensitive (SS) Loss Function [5] | Segmentation Accuracy | MCLID (Mantle Cell Lymphoma) |

Experimental Protocols for Edge-Enhanced Segmentation

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and validating edge-aware segmentation models.

Protocol for Implementing EGBINet

EGBINet addresses blurred edges through a cyclic architecture that enables bidirectional information flow [1].

- Data Preparation:

- Acquire medical image datasets with corresponding ground truth segmentation masks. The ACDC (cardiac), ASC (atrial), and IPFP (knee) datasets are suitable benchmarks.

- Pre-process images: normalize intensity values to a range of [0, 1] and resample all images to a uniform isotropic resolution (e.g., 1.5 mm³).

- Network Architecture Configuration:

- Encoder: Initialize the encoder using a pre-trained VGG19 backbone to extract multi-scale regional features (Ei^1).

- Edge Feature Extraction: Fuse low-level features (E2^1) and high-level global features (E5^1) using multi-layer convolutional blocks to compute initial edge features (D{edge}^1).

- Bidirectional Iteration:

- Feedforward Path: Fuse edge features with multi-level regional features from the encoder to the decoder.

- Feedback Path: Propagate refined region and edge feature representations from the decoder back to the encoder for iterative optimization.

- Feature Fusion: Implement the Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM) to adaptively adjust the weights of local edge and global regional information during fusion.

- Training:

- Use a combined loss function, such as a sum of Dice loss and Binary Cross-Entropy loss.

- Optimize using Adam with an initial learning rate of 1e-4, halving it after every 50 epochs without validation loss improvement.

- Train for a maximum of 400 epochs with a batch size tailored to GPU memory.

- Validation and Analysis:

- Evaluate segmentation performance on a held-out test set using Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC).

- Qualitatively assess the results by visually comparing the sharpness of predicted boundaries against the ground truth, particularly in regions of low contrast.

Protocol for Implementing E2MISeg for Boundary Ambiguity

E2MISeg is designed for smooth segmentation where boundary definition is inherently challenging, such as in PET imaging of lymphomas [5].

- Data Preparation:

- Utilize the provided MCLID dataset or other 3D medical images (e.g., PET, CT, MRI) with poorly defined lesion boundaries.

- Perform standard intensity normalization and resampling to a unified voxel spacing.

- Network Configuration:

- Multi-level Feature Group Aggregation (MFGA): Implement this module to enhance the classification accuracy of edge voxels by explicitly leveraging boundary clues between lesion tissue and background.

- Hybrid Feature Representation (HFR): Construct a block that uses a combination of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformer encoders. The CNN focuses on local texture and edge features, while the Transformer captures long-range contextual dependencies to minimize background noise interference.

- Training with Scale-Sensitive Loss:

- Employ the Scale-Sensitive (SS) loss function, which dynamically adjusts the weights assigned to different image regions based on the magnitude of segmentation error. This guides the network to focus learning capacity on regions with unclear edges.

- Train the model end-to-end using an optimizer like AdamW with a weight decay of 1e-5.

- Validation:

- Beyond the DSC, use a boundary-specific metric like the Boundary F1 (BF1) score to quantitatively evaluate the precision of edge segmentation.

- Perform ablation studies to isolate the performance contribution of the MFGA, HFR, and SS loss components.

Visualization of Edge-Aware Architectures

The following diagrams, generated using DOT, illustrate the core workflows of the featured edge-enhanced segmentation models.

EGBINet Bidirectional Information Flow

E2MISeg Hybrid Feature Representation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Edge-Enhanced Medical Image Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| nnU-Net [25] | Deep Learning Framework | Self-configuring framework for robust medical image segmentation; backbone for many state-of-the-art models. | Serves as the base architecture for TotalSegmentator MRI. |

| TotalSegmentator MRI [25] | Pre-trained AI Model | Open-source, sequence-agnostic model for segmenting 80+ anatomic structures in MRI. | Automated organ volumetry for large-scale population studies. |

| Transformer-based TACM [1] | Neural Network Module | Adaptively fuses multi-scale features by grouping local and global information, improving edge feature quality. | Core component of EGBINet for high-quality feature fusion. |

| Scale-Sensitive (SS) Loss [5] | Optimization Function | Dynamically adjusts learning weights to focus network attention on regions with unclear segmentation edges. | Used in E2MISeg to tackle low-contrast boundaries in lymphoma PET images. |

| EGBINet / E2MISeg Code [1] [5] | Model Implementation | Publicly available code for replicating and building upon the cited edge-aware segmentation models. | Benchmarking new segmentation algorithms on complex clinical datasets. |

| ACDC, ASC, IPFP Datasets [1] | Benchmark Data | Publicly available datasets for training and validating cardiac, atrial, and musculoskeletal segmentation models. | Standardized evaluation and comparison of model performance. |

Methodologies and Clinical Applications of Edge-Enhanced Imaging

Medical image segmentation is a fundamental task in computational pathology and radiology, enabling precise anatomical and pathological delineation for enhanced diagnosis and surgical planning [26] [27]. A persistent challenge in this domain is the accurate segmentation of organ and tumor images characterized by large-scale variations and low-edge pixel-level contrast, which often results in boundary ambiguity [5]. Edge-aware segmentation addresses this critical issue by explicitly incorporating boundary information into the deep learning architecture, significantly improving the model's ability to delineate complex anatomical structures where precise boundaries are diagnostically crucial [1] [28].

The evolution of edge-aware segmentation architectures has progressed from convolutional neural networks (CNNs) like U-Net to more complex frameworks incorporating transformers, state space models, and bidirectional iterative mechanisms [29] [1] [30]. These advancements aim to balance the preservation of local edge details with the modeling of long-range dependencies necessary for global context understanding. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current edge-aware architectures, quantitative performance comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and essential research reagents to facilitate implementation and advancement in this rapidly evolving field.

Taxonomy of Edge-Aware Architectures

Current edge-aware segmentation architectures can be categorized into several paradigms based on their fundamental approach to boundary refinement:

U-Net Enhanced Architectures: Traditional U-Net variants form the foundation of edge-aware segmentation, with innovations focusing on incorporating explicit edge guidance through auxiliary branches. EGBINet introduces a cyclic architecture enabling bidirectional flow of edge information and region information between encoder and decoder, allowing dynamic response to segmentation demands [1]. Similarly, ECCA-UNet integrates Cross-Shaped Window (CSWin) mechanisms for long-range dependency modeling with linear complexity, supplemented by Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) channel attention and an auxiliary edge-aware branch for boundary retention [28].

Transformer-Based Acceleration: Vision Transformer (ViT) adaptations address computational challenges through selective processing strategies. HRViT employs an edge-aware token halting module that dynamically identifies edge patches and halts non-edge tokens in early layers, preserving computational resources for complex boundary regions [29]. These approaches recognize that background and internal tokens can be easily recognized early, while ambiguous edge regions require deeper computational processing.

Few-Shot Learning Frameworks: For scenarios with limited annotated data, specialized architectures have emerged. The Edge-aware Multi-prototype Learning (EML) framework generates multiple feature representatives through a Local-Aware Feature Processing (LAFP) module and refines them through a Dynamic Prototype Optimization (DPO) module [26]. AGENet incorporates spatial relationships through adaptive edge-aware geodesic distance learning, leveraging iterative Fast Marching refinement with anatomical constraints [31].

Hybrid and Next-Generation Models: Recent architectures integrate multiple paradigms for enhanced performance. ÆMMamba combines State Space Modeling efficiency with edge enhancement through an Edge-Aware Module (EAM) using Sobel-based edge extraction and a Boundary Sensitive Decoder (BSD) with inverse attention [30].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance metrics of edge-aware segmentation architectures across public datasets

| Architecture | Dataset | Dice Score (%) | HD (mm) | Params | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECCA-UNet [28] | Synapse CT | 81.90 | 20.05 | - | CSWin + SE attention + Edge branch |

| ECCA-UNet [28] | ACDC MRI | 91.10 | - | - | Channel-enhanced cross-attention |

| E2MISeg [5] | MCLID PET | - | - | - | MFGA + HFR + SS loss |

| HRViT [29] | BTCV | - | - | 34.2M | Edge-aware token halting |

| ÆMMamba [30] | Kvasir | 72.22 (mDice) | - | - | Mamba backbone + EAM |

| AGENet [31] | Multi-domain | 79.56 (1-shot) 81.67 (5-shot) | 11.16 (1-shot) 8.39 (5-shot) | - | Geodesic distance learning |

| Lightweight Evolving U-Net [32] | 2018 Data Science Bowl | 95.00 | - | Lightweight | Depthwise separable convolutions |

Table 2: Architectural components and their functional contributions

| Component | Function | Architectural Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-level Feature Group Aggregation (MFGA) | Enhances edge voxel classification through boundary clues | E2MISeg [5] |

| Hybrid Feature Representation (HFR) | Utilizes CNN-Transformer interaction to mine lesion areas | E2MISeg [5] |

| Scale-Sensitive (SS) Loss | Dynamically adjusts weights based on segmentation errors | E2MISeg [5] |

| Edge-Aware Token Halting | Identifies edge patches, halts non-edge tokens early | HRViT [29] |

| Local-Aware Feature Processing (LAFP) | Generates multiple prototypes for boundary segmentation | EML [26] |

| Dynamic Prototype Optimization (DPO) | Refines prototypes via attention mechanism | EML [26] |

| Bidirectional Iterative Flow | Enables edge-region information exchange | EGBINet [1] |

| Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration (TACM) | Adaptively fuses local edge and global region information | EGBINet [1] |

| Edge-Aware Geodesic Distance | Creates anatomically-coherent spatial importance maps | AGENet [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation Framework for Edge-Aware Segmentation

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing: For optimal performance with edge-aware architectures, medical images require specific preprocessing. For abdominal CT segmentation (e.g., BTCV dataset), implement resampling to isotropic resolution (1.5×1.5×2 mm³) followed by intensity clipping at [-125, 275] Hounsfield Units and z-score normalization [29]. For cardiac MRI segmentation (e.g., ACDC dataset), apply bias field correction using N4ITK algorithm and normalize intensity values to [0, 1] range [28]. For few-shot learning scenarios, implement the episodic training paradigm with random sampling of support-query pairs from base classes, ensuring each task contains K-shot examples (K typically 1 or 5) for each of N classes (usually 2-5) [26] [31].

Edge Ground Truth Generation: Generate binary edge labels using Canny edge detection with σ=1.0 on segmentation masks, followed by morphological dilation with 3×3 kernel to create boundary bands of uniform physical width [26] [1]. Alternatively, for methods employing geodesic distance learning, compute Euclidean Distance Transform (EDT) initialization followed by iterative Fast Marching refinement with edge-aware speed functions [31].

Data Augmentation Strategy: Apply intensive data augmentation including random rotation (±15°), scaling (0.8-1.2×), elastic deformations (σ=10, α=100), and intensity shifts (±20%) [5] [29]. For transformer-based architectures, employ random patch shuffling and patch masking with 15% probability to enhance robustness [28].

Training Protocols

Loss Function Configuration: Implement hybrid loss functions combining region and boundary terms. For E2MISeg, the Scale-Sensitive (SS) loss dynamically adjusts weights based on segmentation errors, guiding the network to focus on regions with unclear edges [5]. For few-shot methods like EML, combine Geometric Edge-aware Optimization Loss (GEOL) with standard cross-entropy and Dice loss, using weight factors of 0.6, 0.3, and 0.1 respectively [26]. For AGENet, integrate geodesic distance maps as spatial weights in the cross-entropy loss to emphasize boundary regions [31].

Optimization Schedule: Train models using AdamW optimizer with initial learning rate of 1e-4, weight decay of 1e-5, and batch size of 8-16 depending on GPU memory [29] [28]. Apply cosine annealing learning rate scheduler with warmup for first 10% of iterations. For few-shot methods, employ meta-learning optimization with separate inner-loop (support set) and outer-loop (query set) updates, with inner learning rate of 0.01 and outer learning rate of 0.001 [26] [31].

Implementation Details: Implement models in PyTorch or TensorFlow, using mixed-precision training (FP16) to reduce memory consumption. For transformer-based architectures, employ gradient checkpointing to enable training with longer sequences. Training typically requires 300-500 epochs for convergence, with early stopping based on validation Dice score [29] [28].

Evaluation Methodology

Performance Metrics: Evaluate segmentation performance using Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice) for region accuracy, Hausdorff Distance (HD) for boundary delineation precision, and for few-shot scenarios, report mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU) across multiple episodes [26] [31]. Compute inference speed (frames per second) and parameter count for efficiency analysis [29] [32].

Statistical Validation: For comprehensive evaluation, perform k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) and report mean±standard deviation across folds. For few-shot methods, evaluate on 1000+ randomly sampled episodes and report 95% confidence intervals [26]. Perform statistical significance testing using paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents for edge-aware segmentation research

| Reagent Solution | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Public Benchmark Datasets | Standardized performance evaluation | ACDC (cardiac), BTCV (abdominal), Synapse (multi-organ), CHAOS (abdominal MRI) [29] [1] [28] |

| Edge Annotation Tools | Generate boundary ground truth | Canny edge detection, Structured Edge Detection, Sobel operators with adaptive thresholding [26] [30] |

| Geometric Loss Functions | Enforce boundary constraints | Scale-Sensitive loss, Geometric Edge-aware Optimization Loss, Geodesic distance-weighted cross-entropy [5] [26] [31] |

| Feature Fusion Modules | Integrate edge and region information | Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration, Hybrid Feature Representation blocks [5] [1] |

| Prototype Optimization | Refine class representations in few-shot learning | Dynamic Prototype Optimization, Local-Aware Feature Processing, Adaptive Prototype Extraction [26] [31] |

| Token Halting Mechanisms | Accelerate transformer inference | Edge-aware token halting with early exit for non-edge patches [29] |

| Bidirectional Information Flow | Enable encoder-decoder feedback | Cyclic architectures with edge-region iterative optimization [1] |

Architectural Diagrams

Edge-Aware Segmentation Workflow

Bidirectional Edge-Region Information Flow

Few-Shot Edge-Aware Learning

Integrating Edge Detection into CNNs and Transformer Models

The integration of edge information into convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and Vision Transformers (ViTs) represents a significant advancement in medical image analysis. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in medical imaging: accurately delineating anatomical structures and pathological regions from images with blurred edges, low contrast, and complex backgrounds [1] [5]. Edge-enhanced deep learning models leverage the strength of CNNs in local feature extraction and ViTs in capturing long-range dependencies, while explicitly incorporating boundary information to improve segmentation precision, facilitate early disease diagnosis, and support clinical decision-making [1] [5]. This technical note outlines the foundational principles, implementation protocols, and application frameworks for successfully integrating edge detection into modern computer vision architectures for medical image enhancement.

Theoretical Foundations and Architectural Frameworks

Comparative Analysis of CNN and Vision Transformer Capabilities

Table 1: Capability comparison between CNN and Vision Transformer architectures for medical image analysis.

| Feature | CNNs | Vision Transformers | Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Feature Extraction | Excellent via convolutional filters [33] | Limited without specific modifications [33] | Excellent (combines CNN front-end) [34] |

| Global Context Understanding | Limited without deep hierarchies [33] | Excellent via self-attention mechanisms [33] | Excellent [34] |

| Data Efficiency | High - effective with limited medical data [33] [34] | Low - requires large datasets [33] [34] | Moderate [34] |

| Computational Efficiency | High - optimized for inference [33] | Low - computationally intensive [33] | Moderate [34] |

| Edge Preservation Capability | Moderate - requires specialized modules [1] | Moderate - requires specialized modules [35] | High - combines strengths of both [35] [1] |

| Interpretability | Good - with saliency maps and Grad-CAM [33] | Moderate - via attention maps [33] | Moderate to Good [33] |

Edge Integration Mechanisms

Contemporary research has established multiple architectural paradigms for integrating edge information into deep learning models for medical image analysis:

Bidirectional Edge Guidance: The EGBINet framework implements a cyclic architecture enabling bidirectional flow of edge information and region features between encoder and decoder, allowing iterative optimization of hierarchical feature representations [1]. This approach directly addresses the limitation of unidirectional information flow in conventional U-Net architectures.

Multi-Scale Edge Enhancement: The MSEEF module integrates adaptive pooling and edge-aware convolution to preserve target boundary details while enabling cross-scale feature interaction, particularly beneficial for detecting small anatomical structures [36].

Hybrid CNN-Transformer with Edge Awareness: The Edge-CVT model combines convolutional operations with edge-guided vision transformers through a dedicated Edge-Informed Change Module (EICM) that improves geometric accuracy of building edges [35]. This approach has been successfully adapted for medical imaging applications.

Progressive Feature Co-Aggregation: The E2MISeg framework employs Multi-level Feature Group Aggregation (MFGA) with Hybrid Feature Representation (HFR) blocks to enhance edge voxel classification through boundary clues between lesion tissue and background [5].

Performance Metrics and Quantitative Evaluation

Comparative Performance of Edge-Enhanced Architectures

Table 2: Performance comparison of edge-enhanced architectures across medical imaging tasks.

| Architecture | Dataset | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGBINet [1] | ACDC, ASC, IPFP | Superior edge preservation and complex structure segmentation accuracy | Bidirectional information flow, iterative optimization of features |

| E2MISeg [5] | MCLID, Public Challenge Datasets | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods in boundary ambiguity | Feature progressive co-aggregation, scale-sensitive loss function |

| Edge-CVT [35] | Adapted for Medical Imaging | F1 scores: 86.87-94.26% on benchmark datasets | Precise separation of adjacent boundaries, reduced spectral interference |

| MLD-DETR [36] | VisDrone2019 (Adaptable) | 36.7% AP50%, 14.5% APs, 20% parameter reduction | Multi-scale edge enhancement, dynamic positional encoding |

| Quantum-Based Edge Detection [37] | Medical Image Benchmarks | Superior to conventional benchmark methods | Quantum Rényi entropy, particle swarm optimization |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementing EGBINet for Medical Image Segmentation

Objective: Establish a reproducible protocol for implementing EGBINet, an edge-guided bidirectional iterative network for medical image segmentation.

Materials and Equipment:

- Medical image dataset (e.g., ACDC, ASC, IPFP) [1]

- Python 3.8+ with PyTorch 1.12.0+

- NVIDIA GPU with ≥8GB VRAM

- VGG19 or ResNet50 as backbone encoder [1]

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Resize all medical images to consistent dimensions (e.g., 256×256 or 512×512)

- Apply normalization using mean and standard deviation of the dataset

- Implement data augmentation: random rotation, flipping, and intensity variations

Network Initialization:

Edge Feature Extraction:

- Extract edge features at multiple scales using the formula: ( D{edge}^1 = \mathrm{Con}(E2^1,E_5^1) ) [1]

- Where ( E2^1 ) represents local edge information and ( E5^1 ) represents global positional information

- Fuse low-level edge features with high-level semantic features

Bidirectional Iterative Processing:

- Implement feedforward path: encoder to decoder with edge feature integration

- Implement feedback path: decoder to encoder for iterative feature refinement

- Apply Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM) for feature fusion [1]

Training Configuration:

- Loss function: Combined dice loss and edge-aware loss

- Optimizer: AdamW with learning rate 1e-4

- Batch size: 8-16 depending on GPU memory

- Training epochs: 200-300 with early stopping

Evaluation:

- Quantitative metrics: Dice coefficient, Hausdorff distance, average symmetric surface distance

- Qualitative assessment: Visual evaluation of boundary accuracy

Protocol 2: Edge-Enhanced Vision Transformer for Medical Image Detection

Objective: Implement a fine-tuned Vision Transformer with edge-based processing for medical image detection.

Materials and Equipment:

- Medical imaging dataset (CT, MRI, or X-ray)

- Pre-trained Vision Transformer model (ViT-Base or ViT-Large)

- Edge computation module

- Hardware: GPU cluster with ≥16GB VRAM

Procedure:

ViT Fine-Tuning:

- Initialize with pre-trained ViT weights (ImageNet-21k or medical imaging domain-specific)

- Adapt input processing for medical image characteristics

- Fine-tune on target medical dataset with progressive unfreezing

Edge-Based Processing Module:

- Generate edge-difference maps before and after image smoothing

- Compute variance from edge-difference maps using formula:

- ( \text{Edge-Variance} = \sigma^2(\text{Edge}{\text{original}} - \text{Edge}{\text{smoothed}}) ) [38]

- Exploit the observation that AI-generated/images with pathologies exhibit different edge variance characteristics

Hybrid Decision Making:

- Combine ViT predictions with edge-variance scores

- Implement weighted fusion: ( \text{Final Score} = \alpha \cdot \text{ViT}{\text{output}} + \beta \cdot \text{Edge}{\text{variance}} ) [38]

- Optimize α and β coefficients on validation set

Validation and Testing:

- Cross-validate on multiple medical imaging domains

- Assess robustness to different imaging modalities and acquisition parameters

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for edge-enhanced medical image analysis.

| Category | Item | Specification/Version | Application Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Datasets | ACDC [1] | 100+ cardiac MRI studies | Benchmarking cardiac segmentation |

| ASC [1] | Atrial segmentation challenge dataset | Evaluating complex structure segmentation | |

| MCLID [5] | 176 patients, multiple centers | Testing robustness on clinical data | |

| Software Libraries | PyTorch [1] | 1.12.0+ | Deep learning framework |

| MONAI | 1.1.0+ | Medical image-specific utilities | |

| OpenCV | 4.7.0+ | Traditional edge detection operations | |

| Backbone Models | VGG19 [1] | Pre-trained on ImageNet | Feature extraction backbone |

| ResNet50 [1] | Pre-trained on ImageNet | Alternative feature backbone | |

| Vision Transformer [38] | Base/Large variants | Global context modeling | |

| Specialized Modules | TACM [1] | Transformer-based adaptive collaboration | Multi-level feature fusion |

| MSEEF [36] | Multi-scale edge-enhanced fusion | Small object boundary preservation | |

| EICM [35] | Edge-informed change module | Boundary accuracy enhancement |

The integration of edge detection into CNNs and Transformer models represents a paradigm shift in medical image analysis, directly addressing the critical challenge of boundary ambiguity in anatomical and pathological segmentation. The architectures and protocols outlined in this document provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these advanced techniques. As the field evolves, future developments are likely to focus on 3D edge-aware segmentation [5], quantum-inspired edge detection methods [37], and more efficient hybrid architectures that optimize the trade-off between computational complexity and segmentation accuracy. The continued refinement of edge-enhanced models promises to further bridge the gap between experimental performance and clinical utility in medical image analysis.

Accurate segmentation of lumbar spine structures—including vertebrae, intervertebral discs (IVDs), and the spinal canal—from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a foundational step in diagnosing and treating spinal disorders. Traditional segmentation methods often struggle with challenges such as low contrast, noise, and anatomical variability, particularly at the boundaries between soft tissues and bone. This case study explores the application of edge-based hybrid models, which integrate edge information directly into deep learning architectures, to enhance the precision of lumbar spine segmentation. By focusing on edge preservation, these methods aim to improve the clinical usability of automated segmentation tools, supporting advancements in medical image analysis within the broader context of image enhancement research.

State of the Field: Lumbar Spine Segmentation Datasets and Baselines

The development of robust segmentation algorithms relies on the availability of high-quality, annotated datasets. One significant publicly available resource is the SPIDER dataset [39], a large multi-center lumbar spine MRI collection. Key characteristics of this dataset are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Overview of the SPIDER Lumbar Spine MRI Dataset

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Volume | 447 sagittal T1 and T2 MRI series from 218 patients [39] |

| Anatomical Structures | Vertebrae, intervertebral discs (IVDs), and spinal canal [39] |

| Annotation Method | Iterative semi-automatic approach using a baseline AI model with manual review and correction [39] |

| Clinical Context | Patients with a history of low back pain [39] |

| Reference Performance | nnU-Net provides a benchmark performance on this dataset, enabling fair comparison of new methods [39] |

This dataset has been instrumental in benchmarking new algorithms. For instance, an enhanced U-Net model incorporating an Inception module for multi-scale feature extraction and a dual-output mechanism was trained on the SPIDER dataset, achieving a high mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) of 0.8974 [40].

Edge-Guided Architectures for Segmentation

A primary challenge in medical image segmentation is the blurring of edges in the final output. To address this, researchers have developed networks that explicitly leverage edge information to guide the segmentation process.

The Edge Guided Bidirectional Iterative Network (EGBINet) is a novel architecture that moves beyond the standard unidirectional encoder-decoder information flow [1]. Its core innovation lies in a cyclic structure that enables bidirectional interaction between edge information and regional features. In its feedforward path, edge features are fused with multi-level region features from the encoder to create complementary information for the decoder. A feedback mechanism then allows region feature representations from the decoder to propagate back to the encoder, enabling iterative optimization of features at all levels [1]. This allows the encoder to dynamically adapt to the requirements of the decoder, refining feature extraction based on edge-preservation needs.

Furthermore, EGBINet incorporates a Transformer-based Multi-level Adaptive Collaboration Module (TACM). This module groups local edge information with multi-level global regional information and adaptively adjusts their weights during fusion, significantly improving the quality of the aggregated features and, consequently, the final segmentation output [1].

Another approach, the Improved Attention U-Net, enhances the standard U-Net architecture by integrating an improved attention module based on multilevel feature map fusion [41]. This mechanism suppresses irrelevant background regions in the feature map while enhancing target regions like the vertebral body and intervertebral disc. The model also incorporates residual modules to increase network depth and feature fusion capability, contributing to more accurate segmentation, including at boundary regions [41].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Selected Segmentation Models

| Model | Key Innovation | Reported Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGBINet [1] | Bidirectional edge-region iterative optimization | Performance on ACDC, ASC, and IPFP datasets | Remarkable performance advantages, particularly in edge preservation and complex structure segmentation |

| Enhanced U-Net [40] | Inception module & dual-output mechanism | mIoU (IoU) | 0.8974 |

| Accuracy | 0.9742 | ||

| F1-Score | 0.9444 | ||

| Improved Attention U-Net [41] | Multilevel attention & residual modules | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | 95.01% |

| Accuracy | 95.50% | ||

| Recall | 94.53% | ||

| VerSeg-Net [42] | Region-aware module & adaptive receptive field fusion | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | 96.2% |

| mIoU | 88.84% |

Experimental Protocols for Edge-Based Segmentation

This section outlines a detailed protocol for implementing and validating an edge-based hybrid segmentation model, drawing from methodologies described in the literature.

Data Preprocessing and Annotation

- Image Standardization: Begin by standardizing all MRI scans to a uniform resolution (e.g., 320x320 pixels). Normalize pixel intensity values by scaling to a range of [0, 1] (e.g., dividing by 255.0) to ensure consistent input for the model [43].

- Ground Truth Preparation: Use manually annotated segmentation masks as the ground truth. For semi-automatic annotation, an iterative approach can be employed: a baseline model provides initial segmentations, which are then meticulously reviewed and manually corrected by trained experts using software like 3D Slicer. These corrected annotations are added to the training set for model retraining, iteratively improving the dataset quality [39].

Model Training and Validation