Foundations of Medical Imaging Engineering and Physics: From Core Principles to AI-Driven Frontiers

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the engineering and physical principles underpinning modern medical imaging.

Foundations of Medical Imaging Engineering and Physics: From Core Principles to AI-Driven Frontiers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the engineering and physical principles underpinning modern medical imaging. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it spans from the foundational concepts of established modalities like CT, MRI, and PET to the cutting-edge integration of artificial intelligence. The content systematically addresses the fundamental physics of image formation, methodological advances in imaging applications, critical challenges in optimization and interpretability, and rigorous frameworks for model validation. By synthesizing these core intents, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to leverage advanced imaging in research and clinical translation, ultimately accelerating diagnostic and therapeutic innovation.

Core Principles and the Evolution of Medical Imaging Modalities

The field of medical imaging engineering relies on fundamental physical principles to visualize internal body structures for clinical analysis and research. These modalities can be broadly categorized based on their underlying physical mechanisms, which dictate their applications, strengths, and limitations in both clinical and research settings. From high-energy ionizing radiation used in X-rays to the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei harnessed in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), each modality provides unique windows into human physiology and pathology. Understanding the physics of image formation is crucial for developing new imaging techniques, improving diagnostic accuracy, and advancing pharmaceutical research through quantitative biomarker development. This technical guide examines the core physical principles, signal formation mechanisms, and quantitative aspects of major medical imaging modalities, providing researchers with a foundation for selecting appropriate imaging methodologies for specific investigational needs.

Core Imaging Modalities: Physical Principles and Mechanisms

X-ray Imaging Physics

X-ray imaging formation relies on the differential attenuation of high-energy photons as they pass through tissues of varying densities. When X-rays, typically produced in a vacuum tube through the acceleration of electrons from a cathode to a metal anode target, interact with biological tissues, several physical processes occur. The photoelectric effect predominates in dense materials like bone, where X-ray photons are completely absorbed, ejecting inner-shell electrons from atoms. Compton scattering occurs when X-ray photons collide with outer-shell electrons, transferring only part of their energy and scattering in different directions. The varying degrees of these interactions across different tissues create the contrast observed in projection radiography. The transmitted X-ray pattern, representing the sum of attenuation along each path, is captured by detectors to form a two-dimensional image. In computed tomography (CT), this process is extended through rotational acquisition, enabling mathematical reconstruction of three-dimensional attenuation maps via filtered back projection or iterative reconstruction algorithms.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Physics

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) utilizes the quantum mechanical property of nuclear spin, exploiting the magnetic moments of specific atomic nuclei when placed in a strong external magnetic field [1]. In clinical and research MRI, hydrogen atoms (1H) are most frequently used due to their natural abundance in biological organisms, particularly in water and fat molecules [1]. When placed in a strong external magnetic field (B0), the magnetic moments of protons align to be either parallel (lower energy state) or anti-parallel (higher energy state) to the direction of the field, creating a small net magnetization vector along the axis of the B0 field [1].

A radio frequency (RF) pulse is applied at the specific Larmor frequency, which is determined by the particle's gyro-magnetic ratio and the strength of the magnetic field [1]. This RF pulse excites protons from the parallel to anti-parallel alignment, tipping the net magnetization vector away from its equilibrium position [1]. Following the RF pulse, the protons undergo two distinct relaxation processes: longitudinal relaxation (T1) and transverse relaxation (T2) [1]. T1 relaxation represents the recovery of longitudinal magnetization along the B0 direction as protons return to their equilibrium state, while T2 relaxation represents the loss of phase coherence in the transverse plane [1]. In practical MRI, the observed signal decay occurs with a time constant T2*, which is always shorter than T2 due to inhomogeneities in the static magnetic field [1].

Spatial encoding in MRI is achieved through the application of magnetic field gradients that vary linearly across space, allowing the selective excitation of specific slices and the encoding of spatial information into the frequency and phase of the signal [1]. The resulting signal is collected in k-space (the spatial frequency domain), and images are reconstructed through a two-dimensional or three-dimensional Fourier transform [1]. By varying the timing parameters of the RF and gradient pulse sequences (repetition time TR and echo time TE), different tissue contrasts can be generated based on their relaxation properties [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Physical Principles of Major Medical Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Signal Origin | Energy Source | Key Physical Interactions | Spatial Encoding Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray/CT | Photon Transmission | Ionizing Radiation (X-rays) | Photoelectric Effect, Compton Scattering | Differential Attenuation, Projection Geometry |

| MRI | Nuclear Spin Resonance | Static Magnetic Field + Radiofrequency Pulses | Precession, T1/T2 Relaxation | Magnetic Field Gradients (Frequency/Phase Encoding) |

| Photoacoustic Imaging | Acoustic Wave Generation | Pulsed Laser Light | Thermoelastic Expansion | Time-of-Flight Ultrasound Detection |

Emerging Modalities: Photoacoustic Imaging

Photoacoustic imaging represents a hybrid modality that combines optical excitation with acoustic detection, leveraging the photoacoustic effect where pulsed laser light induces thermoelastic expansion in tissues, generating ultrasonic waves [2]. This approach provides high-resolution functional and molecular information from deep within biological tissues by exploiting the strong optical contrast of hemoglobin, lipids, and other chromophores while maintaining the penetration depth and resolution of ultrasound [2]. The technique is particularly valuable for imaging vascular networks, oxygen saturation, and molecular targets through exogenous contrast agents, with growing applications in cancer detection, brain functional imaging, and monitoring of therapeutic responses [2]. The physics of signal formation involves optical energy absorption, subsequent thermal expansion, and broadband ultrasound emission, with spatial localization achieved through time-of-flight measurements of the generated acoustic waves using ultrasonic transducer arrays.

Quantitative Imaging and Performance Evaluation

Task-Based Assessment of Image Quality

The rigorous assessment of medical image quality requires specification of both the clinical or research task and the observer (human or computer algorithm) [3]. Tasks are broadly divided into classification (e.g., tumor detection) and estimation (e.g., measurement of physiological parameters) [3]. For classification tasks performed by human observers, performance is typically assessed through psychophysical studies and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, with scalar figures of merit such as detectability index or area under the ROC curve used to compare imaging systems [3]. For estimation tasks typically performed by computer algorithms (often with human intervention), performance is expressed in terms of the bias and variance of the estimate, which may be combined into a mean-square error as a scalar figure of merit [3].

The Gold Standard Problem in Quantitative Imaging

A fundamental challenge in objective assessment of medical imaging systems is the frequent lack of a believable gold standard for the true state of the patient [3]. Researchers have often evaluated estimation methods by plotting results against those from another established method, effectively using one set of estimates as a pseudo-gold standard [3]. Regression analysis and Bland-Altman plots are commonly used for such comparisons, but both approaches have significant limitations [3]. The correlation coefficient (r) in regression analysis depends not only on the agreement between methods but also on the variance of the true parameter across subjects, making interpretation potentially misleading [3]. Bland-Altman analysis, which plots differences between methods against their means, employs an arbitrary definition of agreement (95% of estimates within two standard deviations of the mean difference) that does not indicate which method performs better [3].

Maximum-Likelihood Approach for Modality Comparison

A maximum-likelihood method has been developed to evaluate and compare different estimation methods without a gold standard, with specific application to cardiac ejection fraction estimation [3]. This approach models the relationship between the true parameter value (Θp) and its estimate from modality m (θpm) using a linear model with slope am, intercept bm, and normally distributed noise term εpm with variance σm² [3]. The likelihood function is derived under assumptions that the true parameter value does not vary across modalities for a given patient and is statistically independent across patients, while the linear model parameters are characteristic of the modality and independent of the patient [3]. This framework enables estimation of the bias and variance for each modality without designating any modality as intrinsically superior, allowing objective performance ranking of imaging systems for estimation tasks [3].

Table 2: Figures of Merit for Medical Imaging System Performance Evaluation

| Task Type | Performance Metric | Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Area Under ROC Curve (AUC) | Probability that a randomly chosen positive case is ranked higher than a negative case | Tumor detection, diagnostic accuracy studies |

| Estimation | Bias | Difference between expected estimate and true parameter value | Quantitative parameter measurement (e.g., ejection fraction) |

| Estimation | Variance | Measure of estimate variability around its mean value | Measurement reproducibility, precision assessment |

| Estimation | Mean-Square Error (MSE) | Average squared difference between estimates and true values | Combined accuracy and precision assessment |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Maximum-Likelihood Modality Comparison Protocol

The maximum-likelihood approach for comparing imaging modalities without a gold standard involves a specific experimental and computational protocol [3]. For a study with P patients and M modalities, the following steps are implemented:

Data Collection: Each patient undergoes imaging with all M modalities, with care taken to minimize changes in the underlying physiological state between scans.

Parameter Estimation: For each modality and patient, the quantitative parameter of interest (e.g., ejection fraction) is extracted using the appropriate algorithm for that modality.

Likelihood Function Formulation: The joint probability of the estimated parameters given the linear model parameters ({am, bm, σm²}) is expressed by integrating over the unknown true parameter values (Θp) and assuming statistical independence across patients [3].

Parameter Estimation: The linear model parameters (am, bm, σm²) that maximize the likelihood function are determined through numerical optimization techniques.

Performance Comparison: The estimated parameters for each modality (slope, intercept, and variance) are compared to assess relative accuracy (deviation of am from 1 and bm from 0) and precision (σm²).

This methodology enables researchers to objectively rank the performance of different imaging systems for estimation tasks without requiring an infallible gold standard, addressing a fundamental limitation in medical imaging validation [3].

Standardized Reporting: Node-RADS Criteria

For lymph node assessment in oncology, the Node Reporting and Data System (Node-RADS) provides a standardized methodology for classifying the degree of suspicion of lymph node involvement [4]. This system combines established imaging findings into a structured scoring approach with two primary categories: "size" and "configuration" [4]. The size criterion categorizes lymph nodes as "normal" (short-axis diameter <10 mm, with specific exceptions), "enlarged" (between normal and bulk definitions), or "bulk" (longest diameter ≥30 mm) [4]. The configuration score is derived from the sum of numerical values assigned to three sub-categories: "texture" (internal structure), "border" (evaluating possible extranodal extension), and "shape" (geometric form and fatty hilum preservation) [4]. These scores are combined to assign a final Node-RADS assessment category between 1 ("very low likelihood") and 5 ("very high likelihood") of malignant involvement, enhancing consistency in reporting across radiologists and institutions [4].

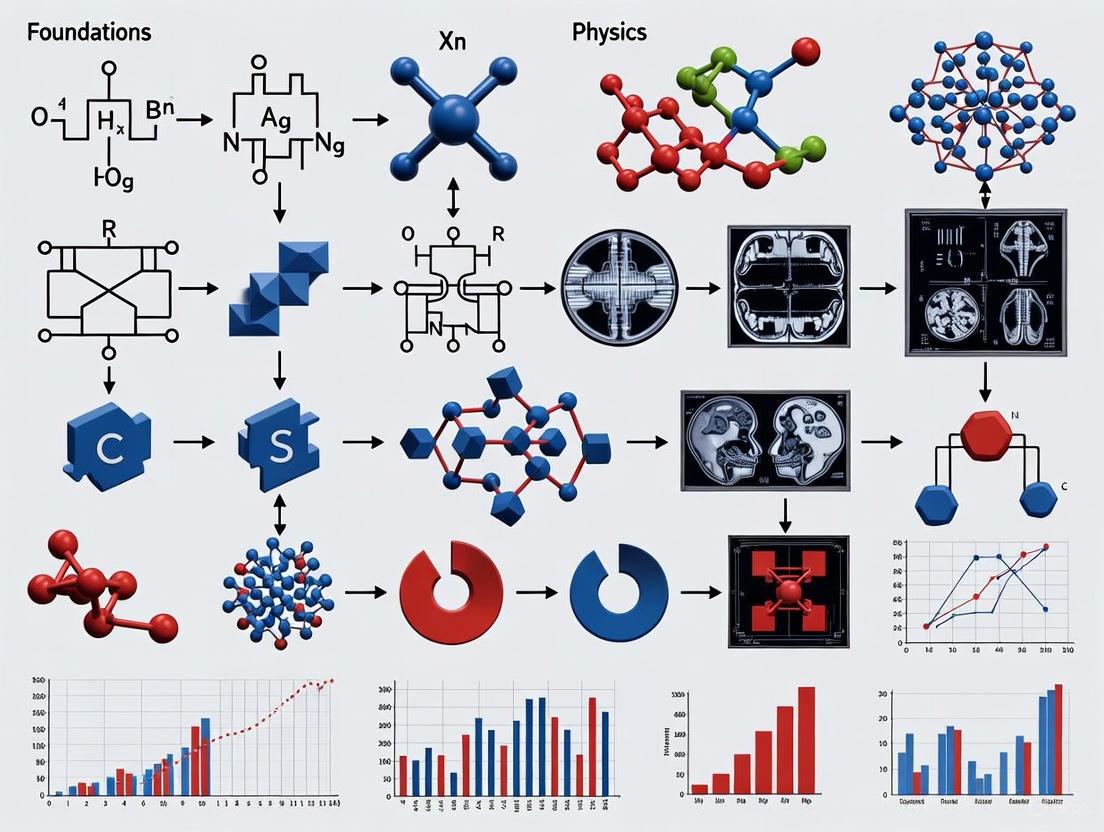

Visualization of Medical Imaging Physics Concepts

MRI Signal Formation and Detection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential physical processes involved in MRI signal formation, detection, and image reconstruction:

Node-RADS Classification Algorithm

The Node-RADS system provides a standardized methodology for lymph node assessment in oncology imaging, as visualized in the following decision workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions for Medical Imaging

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Medical Imaging Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents | Paramagnetic contrast enhancement; shortens T1 relaxation time | Cerebral perfusion studies, tumor vascularity assessment, blood-brain barrier integrity evaluation [1] |

| Iron Oxide Nanoparticles | Superparamagnetic contrast; causes T2* shortening | Liver lesion characterization, cellular tracking, macrophage imaging [1] |

| Radiofrequency Coils | Signal transmission and reception; affects signal-to-noise ratio | High-resolution anatomical imaging, specialized applications (e.g., cardiac, neuro, musculoskeletal) [1] |

| Magnetic Field Gradients | Spatial encoding of MR signal; determines spatial resolution and image geometry | Slice selection, frequency encoding, phase encoding in MRI [1] |

| Photoacoustic Contrast Agents | Enhanced optical absorption for photoacoustic signal generation | Molecular imaging, targeted cancer detection, vascular mapping [2] |

| Computational Phantoms | Simulation of anatomical structures and physical processes | Imaging system validation, algorithm development, dose optimization |

The field of medical imaging represents one of the most transformative progressions in modern healthcare, fundamentally altering the diagnosis and treatment of human disease. This evolution from simple two-dimensional plane films to sophisticated hybrid and three-dimensional imaging systems exemplifies the convergence of engineering innovation and medical physics research. The journey began with Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen's seminal discovery of X-rays in 1895, which provided the first non-invasive window into the living human body [5] [6]. This breakthrough initiated a technological revolution that would eventually incorporate computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and molecular imaging, each building upon foundational principles of physics and engineering.

Medical imaging engineering has progressed through distinct phases, each marked by increasing diagnostic capability. The initial era of projection radiography provided valuable but limited anatomical information, compressing three-dimensional structures into two-dimensional representations. The development of computed tomography (CT) in the 1970s addressed this limitation by enabling cross-sectional imaging, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) later provided unprecedented soft-tissue contrast without ionizing radiation [6] [7]. The contemporary era is defined by hybrid imaging systems that combine anatomical and functional information, and by advanced 3D visualization techniques that transform raw data into volumetric representations [8] [9]. These advancements have created a new paradigm in patient management, allowing clinicians to monitor molecular processes, anatomical changes, and treatment response with increasing precision. This whitepaper examines the historical progression, technical foundations, and future directions of medical imaging systems within the context of engineering and physics research.

The Era of Plane Film: Projection Radiography

The discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen in 1895 marked the genesis of medical imaging, earning him the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 [5] [9]. This foundational technology, initially termed "X-ray radiography" or "plane film," utilized electromagnetic radiation to project internal structures onto a photographic plate, creating a two-dimensional shadowgram of the body's composition [5]. The initial applications focused predominantly on skeletal imaging, allowing physicians to identify fractures, locate foreign objects, and diagnose bone pathologies without surgical intervention [6]. The technology rapidly became standard in medical practice, with fluoroscopy later enhancing its utility by providing real-time moving images [5] [7].

Despite its revolutionary impact, plane film radiography suffered from significant limitations inherent to its design. The technique compressed complex three-dimensional anatomy into a single two-dimensional plane, causing superposition of structures and complicating diagnostic interpretation [10]. Tissues with similar radiodensities, particularly soft tissues, provided poor contrast, limiting the assessment of organs, muscles, and vasculature [5]. Furthermore, the inability to precisely quantify the spatial relationships and dimensions of internal structures restricted its use for complex diagnostic and surgical planning purposes. These constraints drove the scientific community to pursue imaging technologies that could overcome the limitations of projective geometry and provide true dimensional information, setting the stage for the development of cross-sectional and three-dimensional imaging modalities.

Technological Revolutions: From Cross-Sectional to 3D Imaging

Computed Tomography (CT)

The invention of computed tomography in the 1970s by Godfrey Hounsfield represented a quantum leap in imaging technology, effectively ending the reign of plain film as the primary morphological tool [5] [6]. Unlike projection radiography, CT acquired multiple X-ray measurements from different angles around the body and used computational algorithms to reconstruct cross-sectional images [5]. This approach eliminated the problem of structural superposition, allowing clear visualization of internal organs, soft tissues, and pathological lesions. The original CT systems required several minutes for data acquisition, but technological advances led to progressively faster scan times, with modern multi-slice CT scanners capable of acquiring entire body volumes in seconds [5].

The fundamental engineering principle underlying CT is the reconstruction of internal structures from their projections. The mathematical foundation for this process was established by Johann Radon in 1917 with the Radon transform, which proved that a two-dimensional object could be uniquely reconstructed from an infinite set of its projections [5]. In practice, CT scanners implement this principle using a rotating X-ray source and detector array that measure attenuation profiles across the patient. These raw data are then processed using filtered back projection or iterative reconstruction algorithms to generate tomographic images [5]. The transition from analog to digital imaging further enhanced CT capabilities, improving image quality, processing efficiency, and enabling three-dimensional reconstructions through techniques like multiplanar reformation and volume rendering [7] [10].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging emerged in the 1980s as an alternative imaging modality that did not rely on ionizing radiation [6] [7]. Instead, MRI utilizes powerful magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses to manipulate the spin of hydrogen nuclei in water and fat molecules, detecting the resulting signals to construct images with exceptional soft-tissue contrast [6]. This capability made MRI particularly valuable for neurological, musculoskeletal, and oncological applications where differentiation between similar tissues is crucial [10]. The development of functional MRI (fMRI) further expanded its utility by mapping brain activity through associated hemodynamic changes [10].

From a physics perspective, MRI exploits the quantum mechanical property of nuclear spin. When placed in a strong magnetic field, hydrogen nuclei align with or against the field, creating a net magnetization vector. Application of radiofrequency pulses at the resonant frequency excites these nuclei, causing them to emit signals as they return to equilibrium. Spatial encoding is achieved through magnetic field gradients, which create a one-to-one relationship between position and resonance frequency [10]. The engineering complexity of MRI systems lies in generating highly uniform and stable magnetic fields, precisely controlling gradient pulses, and detecting faint radiofrequency signals. Continued innovations in pulse sequences, parallel imaging, and high-field systems have consistently improved image quality, acquisition speed, and diagnostic capability.

Table 1: Evolution of Key Medical Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Decade Introduced | Physical Principle | Primary Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | 1890s | Ionizing radiation attenuation | Bone fractures, dental imaging, chest imaging |

| Ultrasound | 1950s | Reflection of high-frequency sound waves | Obstetrics, abdominal imaging, cardiac imaging |

| CT | 1970s | Computer-reconstructed X-ray attenuation | Trauma, cancer staging, vascular imaging |

| MRI | 1980s | Nuclear magnetic resonance of hydrogen atoms | Neurological disorders, musculoskeletal imaging, oncology |

| PET | 1970s (clinical 1990s) | Detection of positron-emitting radiotracers | Oncology, neurology, cardiology |

| SPECT | 1960s (clinical 1980s) | Detection of gamma-emitting radiotracers | Cardiology, bone scans, thyroid imaging |

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction and Visualization

The transition from two-dimensional slices to true three-dimensional imaging represents another milestone in medical imaging engineering. 3D medical imaging involves creating volumetric representations of internal structures, typically derived from multiple 2D image slices or projections [10]. This process has transformed diagnostic interpretation, surgical planning, and medical education by providing comprehensive views of anatomical relationships [10].

Several technical approaches enable 3D visualization in clinical practice. Volume rendering converts 2D data (such as CT or MRI slices) into a 3D volume, with each voxel assigned specific color and opacity based on its density or other properties [10]. Surface rendering involves extracting the surfaces of structures of interest from 2D data to create a 3D mesh, particularly useful for visualizing organ shape and size [10]. Multiplanar reconstruction reformats 2D image data into different planes, allowing creation of 3D images viewable from various angles [10]. Recent advances in computational photography have also enabled 3D reconstruction from multiple 2D images using photogrammetric techniques, though these are more applicable to external structures [11].

The development of 3D ultrasound created three-dimensional images of internal structures, while 4D ultrasound added the dimension of real-time imaging, allowing physicians to observe the movement of organs and systems [10]. In obstetrics, this technology revolutionized fetal imaging by enabling clinicians to assess development and identify abnormalities more effectively [10].

Hybrid Imaging Systems: The Convergence of Anatomy and Function

The Concept of Anato-Metabolic Imaging

Hybrid imaging represents the logical convergence of anatomical and functional imaging modalities, addressing the fundamental limitation of standalone systems that provide either structure or function but rarely both [8] [9]. The term "anato-metabolic imaging" describes this integration of anatomical and biological information, ideally acquired within a single examination [8] [9]. This approach recognizes that serious diseases often originate from molecular and physiological changes that may precede macroscopic anatomical alterations [8].

The clinical implementation of hybrid imaging began with software-based image fusion, which involved sophisticated co-registration of images from separate systems [8] [9]. While feasible for relatively rigid structures like the brain, accurate alignment throughout the body proved challenging due to the numerous degrees of freedom involved [8]. This limitation drove the development of "hardware fusion" – integrated systems that combined complementary imaging modalities within a single gantry [8] [9]. These hybrid systems, particularly PET/CT and SPECT/CT, revolutionized diagnostic imaging by providing inherently co-registered structural and functional information [8].

SPECT/CT and PET/CT Systems

The first combined SPECT/CT system was conceptualized in 1987 and realized commercially a decade later [9]. These systems integrated single photon emission computed tomography with computed tomography, initially using low-resolution CT for anatomical localization and attenuation correction [8]. Subsequent generations incorporated fully diagnostic CT systems with fast-rotation detectors capable of simultaneous acquisition of 16 or 64 detector rows [9]. This evolution significantly improved diagnostic performance, particularly in oncology, cardiology, and bone imaging [8] [9].

PET/CT development followed a similar trajectory, with the first prototype proposed in 1984 and the first whole-body system introduced in the late 1990s [9]. The combination of positron emission tomography's exceptional sensitivity for detecting metabolic activity with CT's detailed anatomical reference created a powerful tool for cancer staging, treatment monitoring, and neurological applications [9]. The success of PET/CT stems from several factors: logistical efficiency of a combined examination, superior diagnostic information from complementary data streams, and the ability to use CT data for attenuation correction of PET images [9].

PET/MR Systems

The combination of positron emission tomography with magnetic resonance imaging represents the most technologically advanced hybrid imaging platform [9]. Unlike PET/CT, PET/MR integration presented significant engineering challenges due to the incompatibility of conventional PET photomultiplier tubes with strong magnetic fields [9]. Two primary solutions emerged: spatially separated systems with active shielding of photomultiplier tubes, and integrated systems utilizing solid-state photodetectors (avalanche photodiodes or silicon photomultipliers) that function within magnetic fields [9].

PET/MR offers several advantages over PET/CT, including superior soft-tissue contrast, reduced ionizing radiation exposure (particularly beneficial for pediatric and longitudinal studies), and simultaneous rather than sequential data acquisition [9]. This simultaneity enables true temporal correlation of functional and morphological information, opening new possibilities for dynamic studies of physiological processes [9]. The multiparametric assessment capability of PET/MR, combining metabolic information from PET with various MR sequences (diffusion, perfusion, spectroscopy), provides a comprehensive biomarker platform for drug development and personalized medicine [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Hybrid Imaging Systems

| System Type | Key Technical Features | Primary Clinical Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPECT/CT | Gamma camera + 1-64 slice CT; Attenuation correction using CT data [8] [9] | Thyroid cancer, bone scans, parathyroid imaging, cardiac perfusion [8] | Wide range of established radiopharmaceuticals; improved anatomical localization over SPECT alone [8] |

| PET/CT | PET detector + multislice CT; Time-of-flight capability; CT-based attenuation correction [9] | Oncology staging/restaging, treatment response assessment, neurological disorders [9] | Logistically efficient; superior diagnostic accuracy; quantitative capabilities [9] |

| PET/MR | Silicon photomultipliers or APDs for MR compatibility; simultaneous acquisition [9] | Pediatric oncology, neurological disorders, musculoskeletal tumors, research applications [9] | Superior soft-tissue contrast; reduced radiation dose; multiparametric assessment [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

3D Reconstruction Pipeline

The generation of three-dimensional models from two-dimensional image data follows a structured computational pipeline with distinct processing stages. Recent research has optimized this pipeline through specific modifications: (1) setting a minimum triangulation angle of 3° to improve geometric stability, (2) minimizing overall re-projection error by simultaneously optimizing all camera poses and 3D points in the bundle adjustment step, and (3) using a tiling buffer size of 1024 × 1024 pixels to generate detailed 3D models of complex objects [11]. This optimized approach has demonstrated robustness even with lower-quality input images, maintaining output quality while improving processing efficiency [11].

The technical workflow begins with feature detection and matching, where distinctive keypoints are identified across multiple images and correspondences are established [11]. The structure from motion step then estimates camera parameters and sparse 3D geometry [11]. Multi-view stereo algorithms subsequently generate dense point clouds, which are transformed into meshes through surface reconstruction [11]. The final stage involves texture mapping to apply photorealistic properties to the 3D model [11]. For medical applications using CT or MRI data, the pipeline typically employs volume rendering techniques that assign optical properties to voxels based on their intensity values, followed by ray casting to generate the final 3D visualization [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Hybrid Imaging

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ^99mTc-labeled compounds (e.g., ^99mTc-sestamibi, ^99mTc-MDP) | Single photon emitting radiotracer for SPECT imaging [5] [8] | Myocardial perfusion imaging (^99mTc-sestamibi) [8]; Bone scintigraphy (^99mTc-MDP) [8] |

| ^18F-FDG (Fluorodeoxyglucose) | Positron-emitting glucose analog for PET imaging [8] | Oncology (assessment of glucose metabolism in tumors) [8]; Neurology (epilepsy focus localization) |

| ^111In-pentetreotide | Gamma-emitting radiopharmaceutical targeting somatostatin receptors [8] | Neuroendocrine tumor imaging [8] |

| ^123I and ^131I | Gamma-emitting radioisotopes of iodine [8] | Thyroid cancer imaging and therapy [8] |

| Gadolinium-based contrast agents | Paramagnetic contrast agent for MRI | Contrast-enhanced MR angiography; tumor characterization |

| Iodinated contrast agents | X-ray attenuation enhancement for CT | Angiography; tissue perfusion studies |

| Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs) | Solid-state photodetectors for radiation detection [9] | PET detector components in PET/MR systems [9] |

| Quercetin 7-O-(6''-O-malonyl)-beta-D-glucoside | Quercetin 7-O-(6''-O-malonyl)-beta-D-glucoside, MF:C24H22O15, MW:550.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6',7'-Dihydroxybergamottin acetonide | 6',7'-Dihydroxybergamottin acetonide, MF:C24H28O6, MW:412.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The future of medical imaging engineering is advancing along multiple innovative fronts, with artificial intelligence serving as a particularly transformative force. AI and machine learning algorithms are increasingly integrated throughout the imaging pipeline, from image acquisition and reconstruction to analysis and interpretation [2] [10]. Foundation AI models, with their scalability and broad applicability, possess transformative potential for medical imaging applications including automated image analysis, report generation, and data synthesis [2]. The MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI) framework represents a significant open-source initiative supporting these developments, with next-generation capabilities focusing on generative AI for image simulation and vision-language models for medical image co-pilots [2].

Hybrid imaging continues to evolve with emerging modalities like photoacoustic imaging, which combines optical and ultrasound technologies to provide high-resolution functional and molecular information from deep within biological tissues [2]. This technique shows particular promise for cancer detection, vascular imaging, and functional brain imaging [2]. Computational imaging approaches are also advancing, with techniques like lensless holographic microscopy offering sub-micrometer resolution from single holograms and computational miniature mesoscopes enabling single-shot 3D fluorescence imaging across wide fields of view [12].

The integration of imaging with augmented and virtual reality represents another frontier, creating immersive environments for surgical planning, medical education, and patient engagement [10]. These technologies leverage detailed 3D models derived from medical image data to provide intuitive visualizations of complex anatomy and pathology. Additionally, ongoing developments in detector technology, such as solid-state detectors and organ-specific system designs, continue to push the boundaries of spatial resolution, sensitivity, and quantitative accuracy in medical imaging [9]. These innovations collectively promise to enhance the role of imaging as a biomarker in drug development, enabling more precise assessment of therapeutic efficacy and accelerating the development of new treatments.

The historical progression from plane film to hybrid and 3D imaging systems demonstrates remarkable innovation in applying physics and engineering principles to medical challenges. Each technological advancement – from Roentgen's initial discovery to modern integrated PET/MR systems – has expanded our ability to visualize and understand human anatomy and physiology. This evolution has transformed medical imaging from a simple diagnostic tool to an indispensable technology supporting personalized medicine, drug development, and fundamental biological research.

The current era of hybrid and 3D imaging represents not an endpoint but a platform for future innovation. The convergence of artificial intelligence with advanced imaging technologies, development of novel contrast mechanisms and radiotracers, and creation of increasingly sophisticated visualization methods promise to further enhance our capability to investigate and treat human disease. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these advancements offer powerful tools for quantifying disease progression, evaluating treatment response, and understanding pathological processes at molecular and systemic levels. The continued collaboration between imaging scientists, clinical researchers, and industry partners will ensure that medical imaging remains at the forefront of medical innovation, building upon its rich history to create an even more impactful future.

Medical imaging is a cornerstone of modern healthcare and biomedical research, providing non-invasive windows into the human body. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of five fundamental imaging modalities—Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), and Ultrasound—within the context of imaging engineering and physics research. Each modality exploits different physical principles to generate contrast, yielding complementary information about anatomical structure, physiological function, and molecular processes. Understanding these core principles, technical capabilities, and limitations is essential for researchers developing novel imaging technologies, contrast agents, and computational methods, as well as for professionals applying these tools in drug development and clinical translation. This review synthesizes the fundamental engineering physics, current technological advancements, and experimental methodologies that define the state-of-the-art in medical imaging research.

Core Physical Principles and Technical Specifications

The diagnostic utility of each imaging modality is determined by its underlying physical principles and engineering implementation. The interaction of different energy forms with biological tissues creates contrast mechanisms that are captured and reconstructed into diagnostic images.

Fundamental Physics of Image Formation

Computed Tomography (CT) uses X-rays, which are a form of ionizing electromagnetic radiation. As X-rays pass through tissue, their attenuation is governed primarily by the photoelectric effect and Compton scattering [13]. The differential attenuation of these rays through tissues of varying density and atomic composition forms the basis of CT image contrast. The resulting attenuation data from multiple projections are reconstructed using algorithms like filtered back projection or iterative reconstruction to generate cross-sectional images representing tissue density in Hounsfield Units (HU) [14].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) leverages the quantum mechanical properties of hydrogen nuclei (primarily in water and fat molecules) when placed in a strong magnetic field. When exposed to radiofrequency pulses at their resonant frequency, these protons absorb energy and transition to higher energy states. The subsequent return to equilibrium (relaxation) emits radiofrequency signals that are detected by receiver coils. The timing of pulse sequences (repetition time TR, echo time TE) weights the signal toward different tissue properties: proton density, T1 relaxation time (spin-lattice), or T2 relaxation time (spin-spin) [15] [14].

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) detects pairs of gamma photons produced indirectly by a positron-emitting radionuclide (tracer) introduced into the body. When a positron is emitted, it annihilates with an electron, producing two 511 keV gamma photons traveling in approximately opposite directions [16] [17]. Coincidence detection of these photon pairs by a ring of detectors allows localization of the tracer's concentration. The resulting images represent the spatial distribution of biochemical and physiological processes.

Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) also uses gamma-ray-emitting radioactive tracers. Unlike PET, SPECT radionuclides decay directly, emitting single gamma photons [17]. These photons are detected by gamma cameras, typically equipped with collimators to determine the direction of incoming photons. Tomographic images are reconstructed from multiple 2D projections acquired at different angles, showing the 3D distribution of the radiopharmaceutical [16].

Ultrasound utilizes high-frequency sound waves (typically 1-20 MHz) generated by piezoelectric transducers. As these acoustic waves travel through tissues, they are reflected, refracted, scattered, and absorbed at interfaces between tissues with different acoustic impedances [14]. The reflected echoes detected by the transducer provide information about the depth and nature of tissue boundaries. Different modes (B-mode, Doppler, M-mode) process this echo information to create structural or functional images.

Table 1: Quantitative Technical Comparison of Imaging Modalities

| Parameter | CT | MRI | PET | SPECT | Ultrasound |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 0.2-0.5 mm [18] | 0.2-1.0 mm [18] | 4-6 mm [17] | 7-15 mm [17] | 0.1-2.0 mm (depth-dependent) [19] |

| Temporal Resolution | <1 sec | 50 ms - several min | 10 sec - several min | several min | 10-100 ms (real-time) |

| Penetration Depth | Unlimited (whole body) | Unlimited (whole body) | Unlimited (whole body) | Unlimited (whole body) | Centimeter range (depth/frequency trade-off) |

| Primary Contrast Mechanism | Electron Density, Atomic Number | Proton Density, T1/T2 Relaxation, Flow | Radiotracer Concentration | Radiotracer Concentration | Acoustic Impedance, Motion |

| Radiation Exposure | Yes (Ionizing) | No (Non-ionizing) | Yes (Ionizing) | Yes (Ionizing) | No (Non-ionizing) |

Advanced Engineering Implementations

Technological innovations continue to enhance the capabilities of each modality. Dual-Energy CT (DECT) utilizes two different X-ray energy spectra (e.g., 80 kVp and 140 kVp) to acquire datasets simultaneously. The differential attenuation of materials at these energies enables material decomposition, allowing generation of virtual non-contrast images, iodine maps, and virtual monoenergetic reconstructions [13]. Photon-Counting CT (PCCT), an emerging technology, uses energy-resolving detectors that count individual photons and sort them into energy bins, offering superior spatial resolution, noise reduction, and spectral imaging capabilities [13].

In MRI, the development of high-field systems (3T, 7T) increases signal-to-noise ratio, while advanced sequences like diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), arterial spin labeling (ASL), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) provide unique functional and metabolic information. Contrast-enhanced techniques rely on paramagnetic gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs), which alter the relaxation times of surrounding water protons [15]. These are classified as extracellular, blood-pool, or hepatobiliary agents, each with specific pharmacokinetics and indications [15].

Hybrid imaging systems, such as PET/CT, PET/MRI, and SPECT/CT, combine the functional data from nuclear medicine with the anatomical detail of CT or MRI. This integration allows precise localization of metabolic activity and improves diagnostic accuracy [16]. Fusion imaging in ultrasound similarly overlays real-time ultrasound data with pre-acquired CT or MRI datasets, providing enhanced guidance for interventions and biopsies [19].

Research Applications & Experimental Protocols

The selection of an imaging modality in research is dictated by the specific biological question, required resolution, and the nature of the contrast mechanism being probed.

Protocol 1: Tumor Phenotyping with DECT

DECT enables quantitative tissue characterization beyond conventional CT.

- Objective: To differentiate intra-tumoral hemorrhage from iodine contrast staining in a neuro-oncology model.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Animal Model: Employ an orthotopic or transgenic brain tumor model.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire DECT data using a dual-source scanner (e.g., Source 1: 80 kVp, Source 2: 140 kVp) immediately after administration of an iodinated contrast agent.

- Post-processing: Reconstruct virtual monoenergetic images (VMI) at 40-70 keV and material-specific images (iodine and calcium maps) using a three-material decomposition algorithm [13].

- Data Analysis: Measure iodine concentration (mg/mL) within the lesion on iodine maps. On VMI, regions of iodine uptake will show higher attenuation at lower keV, while hemorrhage will not.

- Validation: Correlate DECT findings with post-mortem histology (Perls' Prussian blue for iron in hemorrhage).

Protocol 2: Target Engagement Study with PET

PET is the gold standard for quantitative in vivo assessment of target engagement in drug development.

- Objective: To quantify the occupancy of a novel dopamine D2 receptor antagonist in a non-human primate model.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Radiotracer: Use a specific D2 receptor ligand like [11C]Raclopride.

- Baseline Scan: Perform a 60-minute dynamic PET scan following IV bolus injection of [11C]Raclopride. Acquire arterial blood samples for input function generation.

- Intervention: Administer the candidate therapeutic compound at a predetermined dose.

- Post-Dose Scan: Repeat the dynamic PET scan at the time of expected peak plasma concentration of the therapeutic.

- Kinetic Modeling: Analyze dynamic data using a reference tissue model (e.g., simplified reference tissue model, SRTM) or compartmental modeling with the arterial input function to estimate binding potential (BP~ND~) in the striatum at baseline and post-dose [17].

- Data Analysis: Calculate receptor occupancy as:

Occupancy (%) = [1 - (BP~ND~ post-dose / BP~ND~ baseline)] * 100.

Protocol 3: Liver Fibrosis Staging with Ultrasound Elastography

This protocol assesses tissue mechanical properties, a biomarker for chronic liver disease.

- Objective: To non-invasively stage liver fibrosis in a pre-clinical model of steatohepatitis.

- Experimental Workflow:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize and shave the abdomen for adequate transducer contact.

- System Setup: Use an ultrasound system equipped with a shear wave elastography (SWE) module and a curved array transducer.

- Image Acquisition: Position the transducer in an intercostal view to visualize the right liver lobe. Activate the SWE mode and acquire a cine-loop of the liver while holding the transducer steady.

- Quantification: Place a region of interest (ROI) within the homogeneous color-coded elastography box in the liver parenchyma, avoiding large vessels. Record the mean Young's modulus value (in kilopascals, kPa) from multiple measurements [20].

- Validation: Compare ultrasound-derived stiffness measurements with the histopathological Metavir score from liver biopsy.

Diagram 1: Generic research imaging workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

The fidelity of imaging experiments is critically dependent on the reagents and materials used to generate contrast and ensure experimental validity.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Primary Function | Exemplars & Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Iodinated Contrast Media | Increases X-ray attenuation in vasculature and perfused tissues for CT angiography and perfusion studies. | Iohexol, Iopamidol. Used in DECT to generate iodine maps for quantifying tumor vascularity [13]. |

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents (GBCAs) | Shortens T1 relaxation time, enhancing signal on T1-weighted MRI. | Gadoteridol (macrocyclic, non-ionic). Used for CNS and whole-body contrast-enhanced MRI to delineate pathology [15]. |

| PET Radionuclides & Ligands | Serves as a positron emitter for labeling molecules to track biological processes. | [¹¹C]Raclopride (half-life ~20 min) for neuroreceptor imaging; [¹â¸F]FDG (half-life ~110 min) for glucose metabolism [16] [17]. |

| SPECT Radionuclides & Ligands | Gamma emitter for labeling molecules, allowing longer imaging windows than PET. | Technetium-99m (half-life ~6 hrs), often bound to HMPAO for cerebral blood flow; Indium-111 for labeling antibodies [16] [17]. |

| Anthropomorphic Phantoms | Mimics human tissue properties for validating image quality, dosimetry, and reconstruction algorithms. | 3D-Printed Phantoms. Custom-fabricated using materials tuned to mimic CT Hounsfield Units or MRI relaxation times of various tissues [18]. |

| High-Frequency Ultrasound Probes | Increases spatial resolution for imaging superficial structures in preclinical research. | >20 MHz Transducers. Provide cellular-level resolution for dermatological, ophthalmic, and vascular small-animal imaging [19] [20]. |

| 21,24-Epoxycycloartane-3,25-diol | 21,24-Epoxycycloartane-3,25-diol, MF:C30H50O3, MW:458.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 20S,24R-Epoxydammar-12,25-diol-3-one | 20S,24R-Epoxydammar-12,25-diol-3-one, MF:C30H50O4, MW:474.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Frontiers & Engineering Challenges

The field of medical imaging is rapidly evolving, driven by engineering innovations and computational advancements.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Quantitative Imaging: AI is transforming image reconstruction, denoising, segmentation, and diagnostic interpretation [21] [20]. Deep learning models can automatically detect tumors in breast ultrasound and segment fetal anatomy in obstetric scans [20]. However, challenges such as the "black box" problem, model generalizability across diverse populations, and "alert fatigue" among radiologists need to be addressed through rigorous validation and evolving regulatory frameworks like the EU AI Act [21].

3D Printing of Physical Phantoms: Additive manufacturing enables the creation of sophisticated, patient-specific phantoms for validating imaging protocols and reconstruction algorithms [18]. Current limitations include printer resolution and the limited library of materials that accurately mimic all tissue properties (e.g., simultaneously replicating density, speed of sound, and attenuation) [18].

Miniaturization and Point-of-Care Systems: The proliferation of portable and handheld devices, particularly in ultrasound (POCUS), is democratizing access to diagnostic imaging [19] [20]. These devices empower clinicians in emergency, critical care, and low-resource settings but raise important questions regarding quality assurance and operator training.

Therapeutic Integration: Imaging is increasingly guiding therapy. Techniques like High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) and histotripsy use focused ultrasound energy for non-invasive tumor ablation [20]. Furthermore, focused ultrasound can transiently open the blood-brain barrier, enabling targeted drug delivery to the brain [20].

Diagram 2: Key drivers in imaging technology.

CT, MRI, PET, SPECT, and Ultrasound form a powerful, complementary arsenal in the medical imaging engineering landscape. Each modality, grounded in distinct physical principles, offers unique advantages for probing anatomical, functional, and molecular phenomena in biomedical research. The ongoing convergence of these technologies with artificial intelligence, material science, and miniaturization is pushing the boundaries of diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of the engineering physics, experimental protocols, and emerging capabilities of these modalities is paramount for designing robust studies, interpreting complex data, and driving the next wave of innovation in personalized medicine. The future of medical imaging lies in the intelligent integration of these multimodal data streams to provide a holistic, quantitative view of health and disease.

Radiation is a fundamental physical phenomenon that plays a critical role in medical imaging, therapeutic applications, and scientific research. Understanding the mechanisms by which radiation interacts with biological tissues is paramount for optimizing diagnostic techniques, developing effective radiation therapies, and ensuring safety for both patients and healthcare professionals. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of radiation-tissue interactions, focusing on the biological consequences at molecular, cellular, and systemic levels, while framing these concepts within the foundations of medical imaging engineering and physics research. The content is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require a comprehensive synthesis of current knowledge, experimental methodologies, and safety frameworks governing radiation use in biomedical contexts.

Radiation is broadly categorized as either ionizing or non-ionizing, based on its ability to displace electrons from atoms and molecules [22] [23]. Ionizing radiation, which includes X-rays, gamma rays, and particulate radiation (alpha, beta particles), carries sufficient energy to ionize biological molecules directly. Non-ionizing radiation, encompassing ultraviolet (UV) radiation, visible light, infrared, microwaves, and radio waves, typically lacks this ionization energy but can still excite atoms and molecules, leading to various biological effects [22]. The energy deposition characteristics of ionizing radiation are described by its linear energy transfer (LET), which classifies radiation as either high-LET (densely ionizing, such as alpha particles and neutrons) or low-LET (sparsely ionizing, such as X-rays and gamma rays) [22]. This distinction is crucial as high-LET radiation causes more complex and challenging-to-repair cellular damage per unit dose compared to low-LET radiation [22].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Radiation-Tissue Interaction

Physical Energy Deposition and Direct Effects

The interaction of ionizing radiation with biological matter occurs through discrete energy deposition events. In aqueous systems, these events are classified based on the energy deposited: spurs (<100 eV, ~4 nm diameter), blobs (100-500 eV, ~7 nm diameter), and short tracks (>500 eV) [22]. These classifications help model the initial non-homogeneous distribution of radiation-induced chemical products within biological systems. The direct effect of radiation occurs when energy is deposited directly in critical biomolecular targets, particularly DNA, resulting in ionization and molecular breakage. This direct interaction breaks chemical bonds and can cause various types of DNA lesions, including single-strand breaks (SSBs), double-strand breaks (DSBs), base damage, and DNA-protein cross-links [22].

Table 1: Classification of Radiation Types and Their Key Characteristics

| Radiation Type | Ionizing/Non-Ionizing | LET Category | Primary Sources | Penetration Ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha particles | Ionizing | High | Radon decay, radioactive elements | Low (stopped by skin or paper) |

| Beta particles | Ionizing | Low to Medium | Radioactive decay | Moderate (stopped by thin aluminum) |

| X-rays | Ionizing | Low | Medical imaging, X-ray tubes | High |

| Gamma rays | Ionizing | Low | Nuclear decay, radiotherapy | Very high |

| Neutrons | Ionizing | High | Nuclear reactors, particle accelerators | Very high |

| Ultraviolet (UV) | Non-ionizing (borderline) | N/A | Sunlight, UV lamps | Low (mostly epidermal) |

| Visible light | Non-ionizing | N/A | Sunlight, artificial lighting | Moderate (superficial) |

| Radiofrequency | Non-ionizing | N/A | Communication devices | High |

Indirect Effects and Radical-Mediated Damage

In biological systems composed primarily of water, the indirect effect of radiation plays a significant role in cellular damage. When ionizing radiation interacts with water molecules, it leads to radiolysis, generating highly reactive species including hydroxyl radicals (OH•), hydrogen atoms (H•), and hydrated electrons (eâ»aq) [22] [23]. These reactive products, particularly hydroxyl radicals, can diffuse to critical cellular targets and damage DNA, proteins, and lipids. Approximately two-thirds of the biological damage from low-LET radiation is attributed to these indirect effects [23]. The presence of oxygen in tissues can fix radiation damage by forming peroxy radicals, making well-oxygenated cells generally more radiosensitive than hypoxic cells—a phenomenon with significant implications for radiotherapy of tumors with poor vasculature.

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental pathways of radiation-induced biological damage:

Molecular and Cellular Responses to Radiation

DNA Damage and Repair Mechanisms

DNA represents the most critical target for radiation-induced biological damage due to its central role in cellular function and inheritance. Ionizing radiation creates various types of DNA lesions, with double-strand breaks (DSBs) being particularly significant because of their lethality and potential for mis-repair, which can lead to chromosomal aberrations such as translocations and dicentrics [22]. The complexity of DNA damage depends on radiation quality, with high-LET radiation producing more complex, clustered lesions that are challenging for cellular repair systems to process correctly [22]. Recent research has revealed that ionizing radiation also induces alterations in the three-dimensional (3D) architecture of the genome, affecting topologically associating domains (TADs) in an ATM-dependent manner, which influences DNA repair efficiency and gene regulation [22].

Beyond DNA damage, radiation induces significant alterations to RNA molecules, including strand breaks and oxidative modifications [22]. Damage to protein-coding RNAs and non-coding RNAs can disrupt protein synthesis and gene expression regulation. Specific techniques, such as adding poly(A) tails to broken RNA termini for RT-PCR detection, have been developed to study radiation-induced RNA damage [22]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as crucial regulators of biological processes affected by radiation, with approximately 70% of the human genome being transcribed into RNA while only 2-2.5% codes for proteins, suggesting extensive regulatory networks potentially disrupted by radiation exposure [22].

Cellular Response Pathways and Fate Decisions

Following radiation-induced damage, cells activate complex response networks that determine their fate. The diagram below illustrates the key cellular decision-making pathways after radiation exposure:

Cells exhibit different sensitivity to radiation based on their proliferation status, differentiation state, and tissue of origin. Rapidly dividing cells, such as those in bone marrow and the gastrointestinal system, are particularly vulnerable to radiation damage [23]. At low doses (below 0.2-0.3 Gy for low-LET radiation), some cell types exhibit hyper-radiosensitivity (HRS), where they demonstrate increased radiosensitivity compared to what would be predicted from higher-dose responses [24]. This phenomenon may occur because lower radiation doses fail to activate full DNA damage repair mechanisms efficiently. Additionally, exposure to low radiation doses can sometimes induce an adaptive response, where pre-exposure to low doses protects cells against subsequent higher-dose exposure, potentially through priming of DNA repair and antioxidant systems [24].

Non-Targeted Effects and Bystander Signaling

Radiation effects are not limited to directly irradiated cells. Non-targeted effects, including bystander effects and genomic instability in the progeny of irradiated cells, contribute significantly to the overall biological response [24]. Bystander effects refer to biological responses observed in cells that were not directly traversed by radiation but received signals from irradiated neighboring cells. These effects are mediated through two primary mechanisms: secretion of soluble factors by irradiated cells and direct signaling through cell-to-cell junctions [24]. The radiation-induced bystander effect (RIBE) has the greatest influence on DSB induction at doses up to 10 mGy and follows a super-linear relationship with dose [24]. Additionally, radiation-induced genomic instability (RIGI) manifests as a delayed appearance of de novo chromosomal aberrations, gene mutations, and reproductive cell death in the progeny of irradiated cells many generations after the initial exposure [24].

Quantitative Radiation Dosimetry and Safety Standards

Dosimetry Metrics and Reference Levels

Accurate radiation dosimetry is essential for quantifying exposure, assessing biological risks, and implementing protective measures. The fundamental dosimetric quantities include absorbed dose (energy deposited per unit mass, measured in milligrays, mGy), equivalent dose (accounting for radiation type effectiveness, measured in millisieverts, mSv), and effective dose (sum of organ-weighted equivalent doses, measured in mSv) [25]. For computed tomography (CT) imaging, specific standardized metrics have been established, including CTDIvol (volume CT dose index) and DLP (dose-length product) [26]. Regulatory bodies have established reference levels and pass/fail criteria for various imaging protocols to ensure patient safety while maintaining diagnostic image quality.

Table 2: ACR CT Dose Reference Levels and Pass/Fail Criteria [26]

| Examination Type | Phantom Size | Reference Level CTDIvol (mGy) | Pass/Fail Criteria CTDIvol (mGy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Head | 16 cm | 75 | 80 |

| Adult Abdomen | 32 cm | 25 | 30 |

| Pediatric Head (1-year-old) | 16 cm | 35 | 40 |

| Pediatric Abdomen (40-50 lb) | 16 cm | 15 | 20 |

| Pediatric Abdomen (40-50 lb) | 32 cm | 7.5 | 10 |

Radiation Protection Principles and Safety Implementation

Radiation protection follows three fundamental principles: justification (ensuring the benefits outweigh the risks), optimization (keeping doses As Low As Reasonably Achievable, known as the ALARA principle), and dose limitation (applying dose limits to occupational exposure) [25]. For medical staff working with radiation, practical protection strategies include minimizing exposure duration, maximizing distance from the source (following the inverse square law), and employing appropriate shielding [25]. Personal protective equipment (PPE) for radiation includes lead aprons (typically 0.25-0.5 mm lead equivalence), thyroid shields, and leaded eyeglasses, which can reduce eye lens exposure by up to 90% [25]. Regular use of dosimeters for monitoring cumulative radiation exposure is essential for at-risk healthcare personnel, though compliance remains challenging, with studies indicating that up to 50% of physicians do not wear or incorrectly wear dosimeters [25].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Radiation Effects

In Vitro and In Vivo Radiation Biology Techniques

The study of radiation effects on biological systems employs diverse experimental approaches spanning molecular, cellular, tissue, and whole-organism levels. Standardized protocols have been developed for quantifying specific radiation-induced lesions, such as double-strand breaks, using techniques like the γ-H2AX foci formation assay detected through flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy [22]. For RNA damage assessment, researchers have established methods to detect strand breaks using RT-PCR with poly(A) tail addition to broken RNA termini [22]. Advanced spectroscopic techniques, including Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) and Raman micro-spectroscopy, have been fruitfully employed to monitor radiation-induced biochemical changes in cells and tissues non-destructively [24]. These vibrational spectroscopies provide detailed information about molecular alterations in proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids following radiation exposure.

Recent systems biology approaches have integrated multi-omics data to elucidate complex radiation response networks. A 2025 study employed heterogeneous gene regulatory network analysis combining miRNA and gene expression profiles from human peripheral blood lymphocytes exposed to acute 2Gy gamma-ray irradiation [27]. This approach identified 179 key molecules (23 transcription factors, 10 miRNAs, and 146 genes) and 5 key modules associated with radiation response, providing insights into regulatory networks governing processes such as cell cycle regulation, cytidine deamination, cell differentiation, viral carcinogenesis, and apoptosis [27]. Such integrative methodologies offer comprehensive perspectives on the molecular mechanisms of radiation action beyond single-marker studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for Radiation Biology Studies

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Damage Detection | γ-H2AX antibody, Comet assay, PCR-based break detection | Quantifying DSBs, SSBs, and other DNA lesions | Sensitivity varies by method; γ-H2AX is DSB-specific |

| RNA Damage Assessment | Poly(A) tailing RT-PCR, RNA sequencing | Detecting RNA strand breaks and oxidative damage | Specialized protocols needed for damaged RNA |

| Vibrational Spectroscopy | FT-IR, Raman micro-spectroscopy | Non-destructive biomolecular analysis of cells/tissues | Requires specialized instrumentation and data analysis |

| Cell Viability Assays | Clonogenic survival, MTT, apoptosis assays | Measuring reproductive death and cell survival | Clonogenic assay is gold standard for survival |

| Omics Technologies | Transcriptomics, miRNA profiling, network analysis | Systems-level understanding of radiation response | Bioinformatics expertise required for data interpretation |

| Radiation Sources | Clinical linear accelerators, gamma irradiators, X-ray units | Delivering precise radiation doses to biological samples | Dose calibration and quality assurance critical |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Radiation Studies

The diagram below illustrates a systematic research workflow for investigating radiation effects using integrated experimental approaches:

Emerging Concepts and Therapeutic Applications

Nanotechnology and Radiation Medicine

Nanotechnology offers innovative approaches to enhance the efficacy of radiation therapy while mitigating damaging effects on normal tissues. Nanoparticles can serve as radiosensitizers when incorporated into tumor cells, increasing the local radiation dose through various physical mechanisms, including enhanced energy deposition and generation of additional secondary electrons [22]. High-atomic number (high-Z) nanomaterials, such as gold nanoparticles, exhibit enhanced absorption of X-rays compared to soft tissues, making them promising agents for dose localization in tumor targets. Additionally, nanotechnology-based platforms are being developed for targeted delivery of radioprotective agents to normal tissues, potentially reducing side effects during radiotherapy [22]. These approaches aim to overcome radioresistance in certain tumor types by interfering with DNA repair pathways or targeting hypoxic regions within tumors.

Radiation Modifiers and Drug Development

Research into chemical compounds that modify radiation response represents an active area of therapeutic development. Natural products, including polyphenols, flavonoids, and alkaloids, demonstrate promising radioprotective effects by scavenging reactive oxygen species and enhancing DNA repair mechanisms [28]. Conversely, radiosensitizers such as chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., cisplatin) can enhance radiation-induced damage in tumor cells, particularly when combined with inhibitors of DNA repair pathways like poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors [28]. A 2025 network pharmacology study identified several potential therapeutic compounds for alleviating radiation-induced damage, including small molecules like Navitoclax and Traditional Chinese Medicine ingredients such as Genistin and Saikosaponin D, which may target specific radiation-response pathways identified through systems biology approaches [27].

The field of radiation-tissue interaction continues to evolve with emerging technologies and methodologies. Advanced imaging techniques, artificial intelligence applications in treatment planning and response assessment, and novel targeted radionuclide therapies are expanding the therapeutic window for radiation-based treatments. Future research directions include refining personalized approaches based on individual radiation sensitivity profiles, developing more sophisticated normal tissue protection strategies, and integrating multi-omics data to predict treatment outcomes and long-term effects. These advances, grounded in fundamental understanding of radiation physics and biology, promise to enhance both the safety and efficacy of radiation applications in medicine and beyond.

The field of radiology has long been a fertile ground for the application of artificial intelligence (AI), primarily utilizing deep learning for specific, narrow tasks such as nodule detection or organ segmentation. These traditional models, while effective, are characterized by their limited scope and requirement for vast amounts of high-quality, manually labeled data for each distinct task [29]. The recent emergence of foundation models (FMs) represents a significant paradigm shift, moving beyond conventional, narrowly focused AI systems toward versatile base models that serve as adaptable starting points for numerous downstream applications [29] [30]. These large-scale AI models are pre-trained on massive, diverse datasets and can be efficiently adapted to various tasks with minimal fine-tuning, offering radiology unprecedented capabilities for multimodal integration, improved generalizability, and greater adaptability across the complex landscape of medical imaging [29].

This shift is particularly consequential for medical imaging engineering and physics, as FMs fundamentally alter how we approach image analysis, interpretation, and integration with other data modalities. The transformer architecture, with its attention mechanism that effectively captures long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within data, has become the technical backbone enabling this transition [29]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolution opens new frontiers in precision medicine, enabling more sophisticated analysis of imaging biomarkers, drug response monitoring, and integrative diagnostics that combine imaging with clinical, laboratory, and genomic data [29].

Fundamental Concepts and Technical Architecture

Core Architectural Principles

Foundation models distinguish themselves through several transformative technical characteristics. Unlike traditional AI models engineered for single tasks, FMs are developed through large-scale pre-training using self-supervised learning, allowing them to learn rich data representations by solving pretext tasks such as predicting masked portions of an image or text [29]. This pre-training phase leverages unstructured, unlabeled, or weakly labeled data, significantly reducing the dependency on costly, expert-annotated datasets that have traditionally bottlenecked medical AI development [29].

A defining capability of FMs is their strong transfer learning through efficient fine-tuning. The general knowledge acquired during resource-intensive pre-training can be effectively utilized for new, specific tasks with minimal task-specific data. This facilitates few-shot learning (using only a small number of task-specific examples) and even zero-shot learning (using no examples), where models adapt with substantially less specific data than conventional approaches demand [29]. For instance, an FM pre-trained via self-supervised learning on large chest X-ray datasets may be fine-tuned for rib fracture detection using only dozens of cases, whereas a conventional model might require thousands to achieve comparable performance [29].

Multimodal Integration Framework

For radiology, a development of particular importance is the capacity of FMs to be multimodal, processing and integrating diverse data types including images (X-rays, CT, MRI), text (reports, EHR documents), and potentially more [29]. The technical architecture enabling this integration involves several sophisticated components:

- Modality-specific encoders: These components compress high-dimensional inputs (such as CT scans or text reports) into lower-dimensional embeddings, capturing essential features like tissue density, anatomical structures, and radiological terms [29].

- Cross-modal alignment: Techniques like contrastive learning are employed during pre-training, where the model learns to associate matching image-report pairs by adjusting weights so their embeddings are pulled closer together in a conceptual "shared space" [29].

- Fusion modules: After individual encoders process their respective inputs, fusion mechanisms like cross-attention dynamically weigh the relevance of different parts of one modality based on the content of another [29].

- Decoders: These components transform the fused representations into desired outputs, which could range from generating text reports to segmenting relevant image regions [29].

The Transformer Backbone

The transformer architecture serves as the fundamental backbone for most foundation models, originally revolutionizing natural language processing and subsequently adapting for vision and multimodal scenarios [29]. Its central innovation—the attention mechanism—enables the model to focus on specific elements of the input sequence, effectively capturing long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within data [29]. This capability proves particularly valuable in radiology contexts, where pathological findings often depend on understanding complex anatomical relationships across multiple image slices or combining visual patterns with clinical context from reports.

Experimental Methodologies and Validation Frameworks

Pre-training Approaches for Radiology FMs

The development of radiology-specific foundation models employs several sophisticated methodological approaches, each with distinct experimental protocols:

Masked Autoencoding: This methodology involves randomly masking portions of medical images during training and tasking the model with predicting the missing parts [30]. This self-supervised approach forces the model to learn robust representations of anatomical structures and pathological patterns without requiring labeled data. The experimental protocol typically involves dividing images into patches, masking a significant proportion (often 60-80%), and training the model to reconstruct the original content through iterative optimization.

Contrastive Learning: This approach trains models to learn consistent numerical characterizations of images despite alterations to their content [30]. The experimental design creates positive pairs (different augmentations of the same image) and negative pairs (different images), with the model trained to minimize distance between positive pairs while maximizing distance between negative pairs in the embedding space. This technique proves particularly effective for learning invariances to irrelevant variations in medical images while preserving sensitivity to clinically significant findings.

Report-Image Alignment: Models are trained to associate specific image findings with corresponding radiological descriptions [30]. This methodology typically uses a dual-encoder architecture, with one network processing images and another processing text, trained using contrastive objectives to align matching image-report pairs in a shared embedding space. This approach enables the model to learn clinically meaningful representations grounded in radiological expertise.

Benchmarking and Evaluation Metrics

Rigorous evaluation of foundation models requires multifaceted assessment strategies beyond traditional performance metrics:

Table 1: Comprehensive Evaluation Framework for Radiology Foundation Models

| Evaluation Dimension | Key Metrics | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Accuracy | AUC-ROC, Sensitivity, Specificity, Precision | Retrospective validation on curated datasets with expert annotations |

| Generalizability | Performance degradation across institutions, scanner types, patient demographics | Cross-site validation using datasets from multiple healthcare systems |

| Multimodal Integration | Cross-modal retrieval accuracy, Report generation quality | Task-specific evaluation of image-to-text and text-to-image alignment |

| Robustness | Performance under distribution shift, Adversarial robustness | Stress testing with corrupted data, out-of-distribution samples |

| Fairness | Performance disparities across demographic groups | Subgroup analysis by age, gender, race, socioeconomic status |

Implementation Workflows

The transition from narrow AI to foundation models introduces new operational workflows for research and clinical implementation:

Applications and Performance in Radiology

Transformative Applications

Foundation models enable transformative applications across the radiology workflow, significantly expanding capabilities beyond traditional narrow AI:

Automated Report Generation and Augmentation: FMs can generate preliminary radiology reports based on image findings, with the potential to enhance radiologist productivity and reduce reporting turnaround times [29]. Advanced models can create findings-specific descriptions while maintaining nuanced clinical context, though challenges remain in ensuring accuracy and mitigating hallucination of non-existent findings.

Multimodal Integrative Diagnostics: By simultaneously processing images, textual reports, laboratory results, and clinical history, FMs can provide comprehensive diagnostic assessments that account for the full clinical picture [29]. This capability aligns particularly well with precision medicine initiatives, where treatment decisions increasingly depend on synthesizing diverse data sources.

Cross-lingual Report Translation: The natural language capabilities of FMs enable accurate translation of radiology reports between languages while preserving clinical meaning and terminology precision [29]. This facilitates international collaboration, medical tourism, and care for diverse patient populations.