GGBS vs. RHA Cement Mortars: Performance and Potential for Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of cementitious mortars incorporating Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA) as sustainable alternatives to ordinary Portland...

GGBS vs. RHA Cement Mortars: Performance and Potential for Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

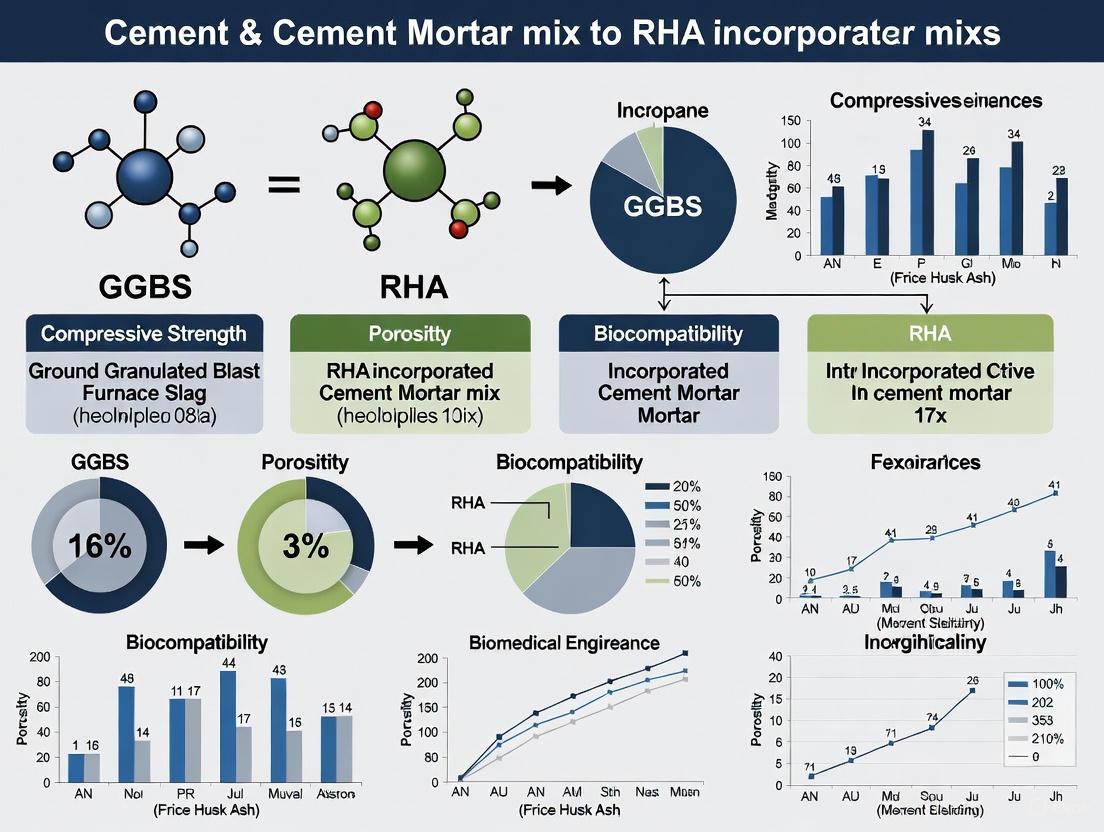

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the performance of cementitious mortars incorporating Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA) as sustainable alternatives to ordinary Portland cement, with a specific focus on their potential for biomedical applications. It explores the foundational chemistry and properties of these materials, detailing methodologies for developing GGBS-RHA blends and addressing key challenges such as workability and setting time. The content includes a rigorous comparative evaluation of mechanical strength, durability, and microstructural characteristics, validated against standards for biomedical materials. Synthesizing current research, this review aims to guide researchers and scientists in drug development and biomaterials towards optimizing these eco-friendly composites for use in bone grafts, drug delivery systems, and other clinical implants.

The Chemistry and Promise of GGBS and RHA as Sustainable Biomaterials

The pursuit of sustainable construction materials has positioned Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA) as prominent supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). As industrial and agricultural by-products, they offer a dual environmental advantage: reducing cement consumption—a significant CO₂ source—and valorizing waste streams [1] [2]. GGBS, a by-product from iron production, and RHA, derived from combusted rice husks, exhibit pozzolanic reactivity, meaning they react with calcium hydroxide in the presence of water to form cementitious compounds like calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) [3]. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of their composition, reactivity, and performance for researchers, particularly those exploring innovative applications in biomedical materials such as bone cements and implant scaffolds, where chemical resistance and biocompatibility are paramount.

Material Composition and Fundamental Properties

The performance of GGBS and RHA is intrinsically linked to their physical and chemical characteristics, which vary based on their origin and processing.

Table 1: Composition and Fundamental Properties of GGBS and RHA

| Property | Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | Rice Husk Ash (RHA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | By-product of the iron manufacturing industry [4] | Combustion residue from rice husks [3] |

| Chemical Composition | CaO (30-50%), SiO₂ (28-38%), Al₂O₃ (8-24%), MgO (1-18%) [2] | Amorphous SiO₂ (~85-95%) [3] |

| Physical Nature | Latent hydraulic [4] | Pozzolanic [3] |

| Reactivity Mechanism | Can hydrate directly with water, but is enhanced by alkaline activators; forms C-S-H, C-A-S-H gels [5] [2] | Reacts with calcium hydroxide (portlandite) to form additional C-S-H gel [3] |

| Key Factors Influencing Reactivity | Chemical composition (CaO, Al₂O₃ content), fineness [4] [2] | Combustion temperature (optimal 500-700°C), fineness, specific surface area [3] |

| Specific Surface Area | -- | High, with a porous structure [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Reactivity and Performance

Standardized experimental methods are crucial for objectively comparing the reactivity of GGBS and RHA. Below are detailed protocols for key tests.

The R³ Test for SCM Reactivity

The R³ (rapid, relevant, and reliable) test is a standardized method to evaluate the pozzolanic reactivity of SCMs in a Portland cement-like environment [4].

- Procedure: The SCM is mixed with Ca(OH)₂, K₂SO₄, and water to form a paste. The reactivity is then assessed via:

- Application: This test is highly sensitive to differences in slag fineness and composition, providing a rapid prediction of their impact on compressive strength in blended systems [4].

Pozzolanic Reactivity Assessment via Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA directly measures the consumption of calcium hydroxide (CH) in blended cement pastes, quantifying the pozzolanic reaction.

- Procedure:

- Prepare cement paste specimens with and without SCM replacement, using a standard water-to-binder ratio (e.g., 0.4) [3].

- Cure the specimens for specific durations (e.g., 1, 3, 7, 28 days).

- Crush and grind the samples to a fine powder.

- Analyze using TGA with a heating range of 50–900°C at a rate of 10°C per minute [3].

- Analysis: The weight loss corresponding to the dehydroxylation of CH (around 400-500°C) is calculated. A higher CH consumption in blended pastes indicates greater pozzolanic activity [3].

Strength Activity Index and Durability Testing in Concrete

Performance is ultimately validated in mortar or concrete mixes.

- Strength Activity Index: The compressive strength of a mortar cube with 20-30% SCM replacement is compared to a control mortar after 7 and 28 days of curing [3].

- Durability in Aggressive Environments: Concrete specimens are immersed in chemical solutions (e.g., 3% HCl, 5% MgSO₄, 3.5% NaCl) for extended periods (e.g., 62 days to 6 months). The residual compressive strength and mass loss are measured to assess chemical resistance [5] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for SCM Investigation

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | The primary SCM under investigation; a latent hydraulic material used as a partial cement replacement [4]. |

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) | The primary SCM under investigation; a highly pozzolanic material used as a partial cement replacement [3]. |

| Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) | The control binder against which the performance of GGBS and RHA blends is compared [7]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | An alkaline activator used in geopolymer synthesis and to enhance the reactivity of SCMs [5] [7]. |

| Sodium Silicate (Na₂SiO₃) | An alkaline activator often used in conjunction with NaOH in geopolymer concrete production [7]. |

| Superplasticizer | A high-range water reducer added to concrete mixes to maintain workability despite the high surface area of SCMs like RHA [5] [3]. |

| Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) | A key reagent in the R³ test and the compound consumed during the pozzolanic reaction with RHA [4] [3]. |

Comparative Performance Data in Cementitious Systems

Direct comparative studies show how GGBS and RHA influence the fresh and hardened properties of cementitious composites.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison of GGBS and RHA

| Performance Metric | GGBS Blends | RHA Blends |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Replacement Level | Up to 50-80% in CAC systems to prevent strength conversion [4] | 10-15% by weight of cement [3] |

| Compressive Strength | Enhances long-term strength; 30% GGBS replacement inhibits strength loss in CAC [4] | 10% replacement can enhance strength by 9.7-20% [3] |

| Chemical Resistance | GGBS-RHA-LECA geopolymer showed 90.6% residual strength in sulfate [5] | 10% RHA improves resistance to sulfuric acid attack by 26.91% [5] |

| Workability (Slump) | -- | Significant reduction in slump; requires superplasticizers [3] |

| Key Gel Products | C-S-H, C-A-S-H (more stable) [5] [2] | C-S-H (denser microstructure) [3] |

GGBS and RHA are both highly valuable SCMs but with distinct characteristics. GGBS is a latent hydraulic material capable of higher replacement levels and contributes significantly to long-term strength and chemical resistance by forming stable gel phases. In contrast, RHA is a highly pozzolanic material, optimal at lower replacement levels (10-15%), renowned for its ability to refine microstructure and drastically improve resistance to chemical attacks, albeit often at the cost of workability.

For biomedical applications such as developing bone cements or scaffolds, the choice depends on the desired property profile. GGBS-RHA hybrid systems appear particularly promising. The high chemical resistance and dense microstructure imparted by RHA, combined with the stable, long-term strength development from GGBS, could be engineered to create durable, biocompatible cementitious materials suited for the harsh physiological environment.

Geopolymerization is a chemical process that transforms aluminosilicate-rich materials into a stable inorganic polymer network, offering a sustainable and high-performance alternative to traditional Portland cement. In the context of biomedical applications research, such as the development of bone implants or specialized medical cements, the performance requirements for materials are exceptionally demanding. These materials must exhibit excellent mechanical strength, chemical durability, and often, specific interaction with biological systems. This review objectively compares the geopolymerization processes and performance outcomes of two key precursor materials: Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag (GGBS), an industrial by-product, and Rice Husk Ash (RHA), an agricultural waste product. The comparative analysis is framed within the broader research context of evaluating GGBS versus RHA-incorporated cement mortar mixes, highlighting how each material contributes to the formation of a stable inorganic matrix suitable for demanding applications.

The fundamental geopolymerization reaction involves a synthesis from aluminosilicate precursors through alkaline activation, resulting in a three-dimensional polymeric network of Si-O-Al-O bonds [8]. This network can manifest as either a sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel or, in calcium-rich systems like GGBS, a calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel, which co-exists with the geopolymeric gel [1]. The specific chemical and mechanical properties of the resulting geopolymer are directly governed by the selection of raw materials and the processing parameters, making the choice between GGBS and RHA a critical research decision.

Comparative Performance Data: GGBS vs. RHA Geopolymer Systems

The performance of geopolymer matrices is critically dependent on the precursor materials. The tables below summarize key quantitative data from experimental studies comparing GGBS and RHA-based systems.

Table 1: Mechanical and Durability Performance of GGBS and RHA Geopolymer Systems

| Performance Parameter | GGBS-based Geopolymer | RHA-based Geopolymer | Test Method / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive Strength | 35–69 MPa [5] [1] | ~39 MPa (30% RHA) [5] | Alkali activation, 7-28 days curing |

| Residual Compressive Strength (after 6 months in aggressive environments) | 86.4% (3% HCl), 90.6% (5% MgSO₄), 91.4% (3.5% NaCl) for 100% GGBS mix with 12M NaOH [5] | 26.91% improvement in acid attack resistance reported for RHA-concrete [5] | Exposure to chemical solutions |

| Predominant Reaction Gel | C-A-S-H and C-S-H [5] [1] | N-A-S-H [5] | SEM/EDAX Analysis |

| Typical NaOH Molarity for Optimal Performance | 8M - 12M [5] | 12M [5] | Alkaline activator concentration |

Table 2: Mix Design and Physical Properties of GGBS and RHA Precursors

| Property | GGBS | RHA |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Gravity | 2.8 [5] | 2.3 [5] |

| Primary Chemical Components | Silica, Alumina, Calcium Oxide [5] [9] | >90% Amorphous Silica [5] [10] |

| Optimal Replacement Level | 50-55% (as OPC replacement) [9] | 15-20% (as OPC replacement) [9] |

| Key Contribution to Matrix | Cementitious properties; enhances early strength and densification [5] [1] | High pozzolanic reactivity; refines pore structure and increases density [5] [10] |

| Effect on Workability | Can improve flow [11] | Reduces workability due to high surface area and porous nature [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Geopolymer Synthesis and Evaluation

Precursor Preparation and Mix Design

The synthesis of high-performance geopolymers for research requires standardized protocols to ensure reproducible results. For GGBS-based systems, the precursor is typically used as-received, benefiting from its inherent hydraulic reactivity. In contrast, RHA must be produced through controlled combustion of rice husk at around 600°C to ensure a high content of reactive amorphous silica rather than crystalline silica, which has low reactivity [5] [10]. A common binary blend for investigation involves 80% GGBS with 20% RHA, which leverages the complementary properties of both materials [5].

The alkaline activator is typically a combination of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃) solutions. The NaOH solution is prepared at varying molarities (e.g., 8M, 10M, 12M) by dissolving pellets in distilled water and allowing it to cool and stabilize before use. The activator is then prepared by mixing the sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate solutions, often at a mass ratio of 1:2.5, and allowing it to cool before combining with the solid precursors [5].

Mixing, Casting, and Curing

The standardized experimental workflow involves several key stages, as visualized below.

The process begins with the dry mixing of solid precursors (GGBS and RHA) to achieve homogeneity. The alkaline activator is then added to the dry mix, and the combination is thoroughly mixed to form a fresh geopolymer mortar or paste. This mixture is cast into molds and often subjected to heat curing at 60–80°C for 24-48 hours to accelerate the geopolymerization reaction, followed by demolding and ambient curing until the testing age [5] [8].

Performance Evaluation Protocols

- Compressive Strength: Tested on cube specimens (e.g., 70.6 mm) at defined ages (3, 7, 28, 56 days) using a compression testing machine following relevant standards [10].

- Durability Assessment: Specimens are immersed in aggressive solutions (e.g., 3% HCl, 5% MgSO₄, 3.5% NaCl) for extended periods (e.g., up to 6 months). The residual compressive strength and mass loss are measured relative to untreated control specimens [5].

- Microstructural Analysis: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is used to examine the microstructure and porosity. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDAX) provides elemental composition, identifying the presence of key gels like N-A-S-H and C-A-S-H [5]. Software like ImageJ can be used with SEM images for quantitative porosity analysis [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Geopolymerization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Geopolymerization | Typical Specification for Research |

|---|---|---|

| GGBS | Calcium-rich precursor; promotes C-A-S-H/C-S-H gel formation for early strength and densification [5] [1]. | Specific gravity ~2.8; high amorphous silica and alumina content [5]. |

| RHA | Silica-rich pozzolan; contributes to N-A-S-H gel formation, refining pore structure and enhancing long-term durability [5] [10]. | Amorphous silica content >90%; specific surface area ~50-60 m²/g [5]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline activator; dissolves Si and Al species from precursors to initiate polymerization [8] [1]. | Pellets ≥97% purity; prepared as aqueous solution (e.g., 8M-14M) [5]. |

| Sodium Silicate (Na₂SiO₃) | Alkaline activator/modifier; provides soluble silica, modifying gel chemistry and enhancing reaction kinetics [8]. | Solution with SiO₂/Na₂O ratio ~2.0-3.2 [5]. |

| Lightweight Expanded Clay Aggregate (LECA) | Functional aggregate; reduces density, provides thermal insulation, and internal curing in lightweight applications [12] [5]. | Particle size 4-10mm; pre-soaked to provide internal moisture [5]. |

Geopolymerization Pathways and Material Performance Relationships

The chemical pathways and resulting material properties are directly influenced by the choice of GGBS and RHA. The following diagram illustrates the distinct reaction mechanisms and performance outcomes.

The GGBS pathway is characterized by the formation of C-A-S-H and C-S-H gels, which are similar to the hydration products in Portland cement but formed in a high-pH environment. This results in rapid strength gain and a highly dense microstructure [5] [1]. In contrast, the RHA pathway primarily forms a N-A-S-H gel, a true geopolymeric network known for its long-term stability and resistance to chemical attacks. The integration of RHA refines the pore structure, thereby reducing permeability and enhancing durability [5].

For biomedical applications, this dichotomy presents a strategic choice. The high strength and density of GGBS-based systems might be advantageous for load-bearing implants, while the refined, stable silicate network of RHA-based systems could offer better bioactivity or controlled degradation profiles. Furthermore, the inclusion of lightweight aggregates like LECA can be tailored to modify the density and thermal properties of the geopolymer, which could be critical for specific biomedical devices or manufacturing processes [12] [5].

The pursuit of sustainable construction materials has become a critical focus in modern materials science, driven by the need to reduce the environmental footprint of the building industry and utilize industrial waste streams. This is particularly relevant for specialized applications, including biomedical research environments where material performance and purity are paramount. Ordinary Portland cement (OPC) production is a significant source of global CO₂ emissions, contributing approximately 5-8% of the worldwide total [13] [14]. For every tonne of cement produced, an average of 0.89 tonnes of CO₂ is emitted [15]. This environmental burden, coupled with the challenge of managing industrial and agricultural waste products, has accelerated research into supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) as partial replacements for OPC.

Among the most promising SCMs are Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag (GGBS), a by-product from iron production, and Rice Husk Ash (RHA), an agricultural waste product from rice processing. When incorporated into cementitious mixes, these materials not only reduce the clinker factor in cement but can also enhance specific material properties. This guide provides an objective comparison of GGBS and RHA-incorporated cement mortar mixes, with specific consideration for their potential in biomedical applications where controlled environments, electromagnetic shielding, and chemical resistance may be required.

Material Properties and Reaction Mechanisms

Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag (GGBS)

GGBS is a latent hydraulic material obtained by quenching molten iron slag from a blast furnace in water or steam, then grinding it to a fine powder. Its chemical composition primarily consists of calcium oxide (CaO), silica (SiO₂), and alumina (Al₂O₃). The glassy, amorphous structure of GGBS is highly reactive in alkaline conditions, such as those provided by Portland cement hydration. GGBS particles are generally finer than OPC, with a typical Blaine fineness of 400-600 m²/kg [13]. Chemically, GGBS contains substantial lime (38.5% CaO) and silica (31.1% SiO₂), which enables its pozzolanic and latent hydraulic properties [16].

The reaction mechanism of GGBS involves both pozzolanic reactions and hydraulic hardening. In the presence of calcium hydroxide (a by-product of OPC hydration), GGBS reacts to form additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) phases, the main strength-giving component in cementitious systems. The higher fineness of GGBS contributes to a filler effect, densifying the microstructure and reducing porosity. Furthermore, GGBS consumption of calcium hydroxide leads to a more refined pore structure and reduced permeability, enhancing durability [14].

Rice Husk Ash (RHA)

RHA is produced by controlled combustion of rice husks, agricultural waste from rice milling. When burned at optimal temperatures (500-700°C), RHA contains 85-95% amorphous silica with high specific surface area and porosity [17]. Its extremely high silica content (90-95% SiO₂) is primarily in reactive amorphous form, making it a highly efficient pozzolanic material [17]. The porous structure and high surface area of RHA contribute to its significant water demand when incorporated into mortar mixes.

The reaction mechanism of RHA is predominantly pozzolanic, where the amorphous silica reacts with calcium hydroxide from cement hydration to form additional C-S-H gel. The high reactivity of RHA leads to rapid consumption of calcium hydroxide, resulting in a densified microstructure with reduced pore size and enhanced interfacial transition zone between aggregate and paste. The resulting C-S-H gel has a lower calcium-to-silica ratio compared to conventional OPC hydration products, contributing to improved mechanical strength and chemical resistance [11].

Experimental Comparison and Performance Data

Methodology for Performance Evaluation

Standard experimental protocols for evaluating cement mortar mixes involve preparing specimens with varying replacement levels of OPC with SCMs, followed by testing for fresh and hardened properties. The typical methodology includes:

Mix Preparation: Mortar mixes are prepared with a standard sand-to-binder ratio and water-to-binder ratio, with OPC partially replaced by GGBS or RHA at predetermined percentages (e.g., 10-30% for RHA, 10-90% for GGBS) [18] [11] [13]. Superplasticizers may be used to maintain constant workability across different mixes [13].

Fresh Properties Testing: Flow table tests according to ASTM C1437 measure workability, with recording of any water requirement adjustments [11].

Mechanical Strength Testing: Compressive strength tests are performed on cube specimens (typically 50mm or 70mm cubes) at standardized ages (7, 28, 56, 90 days) using compression testing machines according to ASTM C109. Flexural strength is determined via three-point bending tests on prism specimens [18] [11] [13].

Specialized Testing: For comprehensive performance evaluation, additional tests may include electromagnetic shielding effectiveness [18], thermal performance at elevated temperatures [19], and microstructural analysis using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction [16] [17].

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Fresh and Mechanical Properties of GGBS and RHA Mortars

| Property | Testing Standard | GGBS Performance | RHA Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workability | ASTM C1437 | Improves flowability; reduces yield stress and plastic viscosity [13] | Reduces workability due to high surface area and porous nature [11] |

| Optimal Replacement Level | - | 30-50% for balanced performance [13] | 10-20% for optimal strength [11] |

| 7-Day Compressive Strength | ASTM C109 | Lower than control at high replacement levels; 10% replacement shows minimal reduction [18] | Varies with replacement level; 10% replacement shows comparable strength [18] |

| 28-Day Compressive Strength | ASTM C109 | Enhanced strength at 30-50% replacement; 40% replacement shows optimal performance [13] | Improved strength; optimal at 10-20% replacement [18] [11] |

| Long-Term Strength (56-90 days) | ASTM C109 | Significantly enhanced due to continued pozzolanic reactions [13] | Continued strength gain due to pozzolanic reactions [11] |

| Flexural Strength | ASTM C348 | Improved with optimal replacement (40% GGBS) [13] | Enhanced, particularly in combination with UGGBS [11] |

| EM Shielding Effectiveness | Custom setup | Improves absorption parameters at 10-30% replacement [18] | Enhances electromagnetic absorption capabilities [18] |

Table 2: Durability and Specialized Properties for Biomedical Applications

| Property | Testing Method | GGBS Performance | RHA Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonation Resistance | Phenolphthalein indicator test [14] | Lower resistance than OPC; requires proper curing [14] | Improved due to reduced Ca(OH)₂ content [14] |

| Chloride Ion Penetration | ASTM C1202 | Significantly reduced permeability and chloride ingress [13] | Enhanced resistance due to pore refinement [11] |

| Thermal Performance | Exposure to elevated temperatures (100-700°C) [19] | Maintains better residual strength at elevated temperatures [19] | Improved thermal resistance due to stable silica structure [19] |

| Microstructure | SEM, XRD analysis | Denser matrix with reduced porosity [13] | Refined pore structure with reduced Ca(OH)₂ [11] [17] |

| Environmental Impact | CO₂ footprint calculation | Reduces CO₂ emissions by utilizing industrial waste [13] [14] | Agricultural waste utilization; circular economy [11] [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Cement Mortar Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Portland Cement | ASTM C150 Type I/II | Primary binder and control reference |

| Ground Granulated Blast-Furnace Slag | ASTM C989 Grade 100 | Supplementary cementitious material with latent hydraulic properties |

| Rice Husk Ash | High amorphous silica content (>85%) | Highly reactive pozzolanic material |

| Ultrafine GGBS (UGGBS) | High fineness (>600 m²/kg) | Enhanced reactivity and filler effect |

| Standard Sand | ASTM C778 | Standardized fine aggregate for mortar mixes |

| Superplasticizer | ASTM C494 Type F/P | Water reducer for workability control |

| Sodium Hydroxide | Reagent grade (98% purity) | Alkaline activator for geopolymer studies |

| Sodium Silicate | Reagent grade (Na₂SiO₃) | Alkaline activator for geopolymer studies |

| Micronized Biomass Silica | High purity silica from agricultural waste | Enhanced pozzolanic reactivity in specialized mixes |

Performance Analysis and Discussion

Workability and Rheology

The fresh properties of mortar mixes significantly impact their application and placement. GGBS consistently improves the rheological behavior of cement mortars, reducing both plastic viscosity and yield stress, which enhances flowability and pumpability [13]. This property is particularly advantageous for applications requiring precise placement or injection in biomedical device embedding or specialized laboratory constructions.

In contrast, RHA incorporation reduces workability due to its high specific surface area and porous nature, which increases water demand [11]. This challenge can be mitigated through the use of water-reducing admixtures or by combining RHA with other SCMs that improve flow characteristics. The combination of RHA with ultrafine GGBS (UGGBS) has been shown to significantly improve flow characteristics while maintaining the pozzolanic benefits of RHA [11].

Mechanical Strength Development

The compressive strength development pattern differs significantly between GGBS and RHA mixtures. GGBS mixtures typically exhibit slower early-age strength gain (up to 7 days) but demonstrate significantly enhanced long-term strength development due to prolonged pozzolanic reactions [13]. The optimal replacement level for GGBS in mortar mixes ranges between 30-50%, with 40% replacement showing particularly strong performance in compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strength [13].

RHA mixtures show more varied strength performance depending on the replacement level. At optimal replacement levels (10-20%), RHA can enhance 28-day compressive strength due to its high pozzolanic reactivity and micro-filler effect [11]. However, higher replacement levels may lead to reduced strength unless additional measures such as particle size optimization or chemical activation are implemented. The blend of GGBS and UGGBS with RHA has demonstrated superior mechanical performance in ternary mix systems [11].

Specialized Properties for Biomedical Applications

For potential biomedical research environments, several specialized properties become relevant:

Electromagnetic Shielding: Both GGBS and RHA have demonstrated capability to improve electromagnetic wave absorption parameters in cement-based composites [18]. This property could be valuable for creating shielded environments for sensitive electronic medical equipment or specialized laboratories.

Thermal Performance: At elevated temperatures (100-700°C), both materials contribute to maintaining residual mechanical properties, with GGBS-based geopolymer concrete showing particularly enhanced fire resistance [19]. This characteristic could be beneficial for specialized high-temperature applications or safety considerations in laboratory settings.

Microstructural Refinement: Both GGBS and RHA contribute to microstructural densification through pore refinement and reduced permeability [11] [13]. This enhanced microstructure could potentially improve resistance to chemical attacks from disinfectants or specialized cleaning agents used in biomedical environments.

Experimental Workflow for Mortar Performance Evaluation

The comparative analysis of GGBS and RHA-incorporated cement mortar mixes reveals distinct advantages and optimal application scenarios for each material. GGBS excels in applications requiring enhanced workability, pumpability, and long-term strength development, with optimal performance at 30-50% replacement levels. RHA offers superior pozzolanic reactivity and mechanical strength at lower replacement levels (10-20%), particularly when its water demand challenges are properly managed.

For biomedical research applications, where specialized requirements such as electromagnetic shielding, thermal resistance, and chemical durability may be needed, both materials offer valuable properties that can be leveraged through optimized mix designs. Ternary blends combining GGBS, UGGBS, and RHA may provide the most balanced performance profile, capitalizing on the complementary characteristics of these sustainable materials while addressing their individual limitations.

The integration of these industrial and agricultural by-products into cementitious materials represents a significant opportunity to advance sustainability in construction while meeting the specialized performance requirements of biomedical research environments. Future research should focus on durability characterization under specific chemical exposures relevant to biomedical settings and the development of standardized testing protocols for these specialized application scenarios.

The pursuit of advanced biomaterials for bone repair and tissue engineering demands materials that are not only mechanically competent and biocompatible but also environmentally sustainable. Traditional bioceramics and synthetic bone grafts often involve energy-intensive manufacturing processes. In this context, investigating sustainable alternative materials is crucial. This guide provides a performance comparison of two such materials—Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA)—when incorporated into cementitious mortar mixes for potential biomedical applications. The comparison is framed by their material properties, chemical composition, and performance in simulated bodily environments, highlighting their potential and challenges as bone-analogous materials.

GGBS is a by-product from the iron-making industry in blast furnaces, with an annual global output of approximately 338–390 million tons [20]. Its chemical composition is predominantly CaO (30-50%), SiO₂ (28-40%), and Al₂O₃ (8-24%) [21] [13] [20]. The presence of significant calcium and silica is a key rationale for its biomedical exploration, as these are foundational elements of natural bone mineral. Furthermore, its latent hydraulic reactivity allows it to form stable, dense reaction products like calcium aluminosilicate (C-A-S-H) gel when activated [21] [20], a structure that could be tailored to mimic the bone matrix.

RHA is derived from the controlled combustion of rice husk, an agricultural waste. Its primary component is highly reactive amorphous silica (SiO₂ content often exceeding 85-91%) [10] [22]. This high silica content provides excellent pozzolanic activity, reacting with calcium hydroxide to form additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel [22] [23]. From a biomedical perspective, silica is a known bioactive material, playing a critical role in bone formation and biomineralization. The porous, amorphous structure of RHA also presents a potential scaffold for cell attachment and bone ingrowth.

The synergy of combining these materials is also of significant interest. RHA-based alkali-activated composites (AAC) blended with GGBS have been explored in construction, demonstrating enhanced strength and microstructural density [24]. This synergy could be leveraged in biomaterials to create a composite with optimized concentrations of calcium and silica, potentially accelerating the formation of a bioactive hydroxyapatite layer in vivo.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes the key properties of GGBS and RHA mortar mixes based on data from construction materials research, which serve as proxies for their potential performance in biomedical contexts.

Table 1: Comparative properties of GGBS and RHA mortar mixes

| Property | GGBS Mortar Mixes | RHA Mortar Mixes | Remarks for Biomedical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Replacement Level | 30-50% of cement [13]; High-volume (70-95%) is feasible with activators [20] | 10-20% as sand replacement [10]; 15-30% as cement replacement [22] [23] | Indicates the proportion for stable composite formation. High-volume GGBS requires alkaline activation. |

| Compressive Strength | Long-term strength significantly enhanced; can exceed OPC concrete [13]. Optimal mixes (30-50% GGBS) show excellent strength development. | Up to 33.8% increase reported with 3% ZrO₂ & 10% RHA vs. control [10]. Enhanced by ~20% with 15% RHA & 10% seashell powder [23]. | Proxy for mechanical competence and load-bearing potential in non-critical bone defects. |

| Reaction Products | C-A-S-H gel, Mg-Al Layered Double Hydroxide (LDH) [20]. | Additional C-S-H gel from pozzolanic reaction [22] [23]. | C-S-H and C-A-S-H are analogous to the inorganic component of bone (hydroxyapatite). |

| Porosity & Density | Lowers permeability and refines pore structure [13] [20]. Microstructure becomes denser with age. | Significantly reduces porosity (18-22%) [23]. High silica content leads to a denser matrix [22]. | Low porosity is desirable to prevent bacterial colonization; controlled micro-porosity is needed for osseointegration. |

| Chemical Resistance | Enhanced resistance to chloride and sulfate attacks [13]. | Improved chloride penetration resistance and sulfate resistance [22] [23]. | Indicates potential stability in the corrosive, ionic environment of the human body. |

| Key Chemical Composition | Rich in CaO, SiO₂, Al₂O₃, MgO [21] [13]. | Very high SiO₂ (amorphous), with minor K₂O, P₂O₅ [10] [22]. | Ca and Si are bioactive. Mg can enhance osteogenesis; P is a component of bone mineral. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Performance Tests

The following methodologies are adapted from standardized construction materials testing and can be viewed as foundational protocols for initial in vitro biomaterial assessment.

Compressive Strength Testing

Objective: To evaluate the mechanical integrity of the set mortar, analogous to the mechanical strength required for bone cement or scaffolds.

- Specimen Preparation: Prepare mortar mixes with a standard binder-to-sand ratio (e.g., 1:3). Cast specimens in 70.6 mm cube molds. For GGBS mixes, use alkaline activators (e.g., sodium silicate and sodium hydroxide) [25]. For RHA mixes, replace a portion of cement or sand as per the experimental design [10] [23].

- Curing: Cure specimens under specified conditions (ambient temperature or elevated temperature for geopolymers) for set periods (e.g., 3, 7, 28, and 56 days) in a humidity chamber [25] [24].

- Testing: Test the cubes for compressive strength using a universal testing machine at a specified load rate as per standards like IS 516:2018 [10]. The compressive strength is calculated as the maximum load carried by the specimen divided by its cross-sectional area.

Porosity and Chloride Ion Penetration Resistance

Objective: To assess the microstructural density and durability, which correlates with the material's ability to resist degradation and biofilm formation.

- Apparatus: Rapid Chloride Permeability Test (RCPT) setup, vacuum saturation setup, weighing balance.

- Procedure:

- Porosity: Saturate dried, pre-weighed disc-shaped specimens under vacuum. Weigh the specimens in water and in a saturated surface-dry condition. Calculate the total porosity based on the volume of permeable pore space [22] [23].

- Chloride Resistance: Subject the saturated specimens to an RCPT, where a voltage is applied across the specimen, and the total charge passed in 6 hours is measured. A lower charge passed indicates higher resistance to chloride ion penetration [26] [22].

Microstructural Analysis

Objective: To characterize the reaction products, pore structure, and elemental composition, which are critical for understanding bioactivity.

- Specimen Preparation: Crush hardened samples and collect fragments. Stop the hydration process using solvent exchange. Coat samples with a conductive material (e.g., gold) for SEM.

- Techniques:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Examine the surface morphology, identify gel structures (C-S-H, C-A-S-H), and observe pore distribution at high magnification [25] [24].

- Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) Analysis: Determine the elemental composition (Ca, Si, Al, etc.) at specific points or areas on the SEM sample [24].

- X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Identify the crystalline phases present (e.g., portlandite, quartz) and confirm the amorphous nature of the binder gels by analyzing the diffraction patterns [10].

The logical workflow for a comprehensive evaluation of these materials is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for preparing and testing GGBS- and RHA-incorporated mortars

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance in Biomedical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | Latent hydraulic aluminosilicate precursor. Requires activation to form a solid binder. | Source of calcium and silica for potential bone-analogous mineral formation. |

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) | Highly reactive pozzolanic material rich in amorphous silica. | Source of bioactive silica; its porous structure may mimic bone scaffolding. |

| Alkaline Activators | Typically a combination of Sodium Silicate (Na₂SiO₃) and Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) solutions. | Essential for dissolving GGBS and RHA to initiate geopolymerization. Alkali concentration impacts reaction kinetics and final structure. |

| Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) | Primary binder in control mixes or as a co-binder. | Provides a baseline for comparison and supplies calcium hydroxide for RHA's pozzolanic reaction. |

| Fine Aggregate | Standard sand meeting specific gradation standards (e.g., IS 383:1970). | Provides the composite's granular skeleton, contributing to its overall mechanical strength. |

| Superplasticizer | High-range water-reducing admixture (e.g., ASTM C494 Type F). | Adjusts workability without increasing water content, ensuring a dense final microstructure with minimal voids. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Ion solution with inorganic ion concentrations nearly equal to human blood plasma. | Critical for bioactivity testing. Used to assess the material's ability to form a hydroxyapatite layer on its surface in vitro. |

This comparison guide outlines the fundamental properties of GGBS and RHA as potential starting points for sustainable biomaterial development. The experimental data, primarily from construction science, shows that both materials can form stable, strong, and dense matrices with tailored chemistry—GGBS being a calcium-rich option and RHA a silica-rich alternative. Their demonstrated chemical resistance suggests potential stability in the human body, while their key elemental compositions are intrinsically linked to bone bioactivity. Future research must pivot towards direct in vitro biocompatibility and bioactivity testing, including cell viability assays and immersion studies in SBF, to validate their true potential for biomedical applications such as bone grafts, cement, or porous scaffolds. The synergy of GGBS and RHA in a single composite also presents a compelling avenue for developing a new class of sustainable, multi-component bioceramics.

Developing and Processing GGBS-RHA Blends for Biomedical Formulations

The pursuit of sustainable and high-performance construction materials has led to significant research into optimizing the use of industrial and agricultural by-products in cementitious systems. For researchers exploring specialized applications, including biomedical contexts such as drug development platforms or bioreactor design, understanding the precise performance characteristics of these materials is paramount. This guide provides an objective comparison of mortar mixes incorporating Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and Rice Husk Ash (RHA) as partial replacements for ordinary Portland cement (OPC), analyzing binary, ternary, and quaternary mix designs. The performance is evaluated based on mechanical strength, durability, microstructural properties, and sustainability indicators, with all data synthesized from recent experimental studies to support informed material selection for advanced research applications.

Comparative Performance Data of Mix Designs

Binary Blended Mixtures

Binary blends involve replacing a portion of OPC with a single supplementary cementitious material (SCM), such as GGBS or RHA. Experimental studies have demonstrated that these substitutions significantly influence material properties.

GGBS Binary Blends: Research indicates that a binary mortar with 30% GGBS substitution for OPC demonstrates satisfactory long-term performance. When exposed to real-world conditions similar to an underground garage (XC3 exposure class), this mix showed a refined pore structure and improved durability over time due to continued hydration reactions [27]. The presence of GGBS promotes the formation of additional CSH phases, leading to a denser microstructure [27].

RHA Binary Blends: RHA is prized for its high pozzolanic reactivity, attributable to its amorphous silica content, which can exceed 90% [10]. As a sand replacement, a blend with 10% RHA demonstrated a significant 33.8% increase in 28-day compressive strength compared to a control mortar when combined with a 3% zirconia cement replacement [10]. The optimal replacement level for cement with RHA generally falls between 10% and 30% by weight, with studies showing enhancements in compressive, flexural, and split tensile strength [28].

Ternary Blended Mixtures

Ternary binders incorporate two different SCMs alongside clinker, often yielding synergistic effects that enhance overall performance beyond what binary systems can achieve [27].

GGBS and Fly Ash (SF): A ternary blend with 15% GGBS and 15% fly ash has shown exceptional mechanical performance, delivering the best results at 250 days among several tested blends in long-term studies. The combination of slag's hydraulic properties and fly ash's pozzolanic activity creates a more refined and stable microstructure over time [27].

GGBS and Limestone (SL): A mix containing 15% GGBS and 15% limestone is another viable ternary option, conforming to standardized commercial cement type CEM II/B [27]. The GGBS contributes to hydration and pore refinement, while the limestone primarily acts as a filler, enhancing the physical structure of the mortar [27].

RHA and Metakaolin: Research into geopolymer cements using RHA and metakaolin with an alkaline activator has achieved a compressive strength of 0.80 MPa at 7 days under optimized production parameters. The statistical model for this mix showed high reliability (β values < 0.05) for predicting strength development [29].

Quaternary Blended and Alkali-Activated Mixtures

More complex mixtures, including quaternary blends and alkali-activated composites (AAC), represent the forefront of sustainable binder technology.

RHA-GGBS-Bauxite AAC: A study optimizing RHA-based AAC blended with GGBS and bauxite developed two key mixes. For oven-cured specimens, the optimal mix was 750 kg/m³ RHA, 1100 kg/m³ bauxite, and 150 kg/m³ GGBS, achieving compressive strengths of 18-24 MPa. For ambient-cured applications, the optimal proportions were 945.3 kg/m³ RHA, 889.1 kg/m³ bauxite, and 165.6 kg/m³ GGBS [24]. Microstructural analysis confirmed the formation of gel phases and partial crystallinity, contributing to the material's strength [24].

Fly Ash-GGBS Geopolymer: In geopolymer bricks, a mix with 20% GGBS content in fly ash, activated with 10M NaOH and cured at 80°C for 28 days, yielded a very high compressive strength of 49.63 MPa. The inclusion of GGBS enhanced the bulk density and durability while reducing porosity and water absorption, creating a compact matrix with abundant C-S-H formation [30].

Table 1: Summary of Optimal Mix Designs and Their Performance

| Mix Type | Precursor Components & Ratios | Key Performance Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary | OPC + 30% GGBS | Improved long-term microstructure refinement and durability under XC3 exposure. | [27] |

| Binary | OPC + 10-30% RHA (Cement replacement), 10% RHA (Sand replacement) + 3% ZrO₂ | 33.8% increase in 28-day compressive strength; enhanced pozzolanic reactivity. | [28] [10] |

| Ternary | OPC + 15% GGBS + 15% Fly Ash | Best mechanical performance at 250 days; synergistic microstructural refinement. | [27] |

| Ternary | OPC + 15% GGBS + 15% Limestone | Conforms to CEM II/B standard; filler effect and hydration. | [27] |

| Ternary (Geopolymer) | RHA + Metakaolin + Alkaline Activator | Optimized 7-day strength of 0.80 MPa; reliable predictive model (R²=0.8951). | [29] |

| Quaternary (AAC) | RHA + GGBS + Bauxite + Alkaline Activator | Compressive strength of 18-24 MPa; dense microstructure with gel formation. | [24] |

| Quaternary (Geopolymer) | Fly Ash + GGBS (20%) + Sand + Alkaline Activator (10M) | High compressive strength (49.63 MPa); low porosity and water absorption. | [30] |

Table 2: Sustainability and Durability Indicators

| Material Property | GGBS-Based Mixes | RHA-Based Mixes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Hydraulic activity forming CSH phases [27]. | Pozzolanic reaction with Ca(OH)₂ to form secondary CSH [28] [10]. |

| Key Durability Traits | Refined pore network; improved resistance to chlorides and sulfates [27]. | Reduced permeability; enhanced resistance to chloride, sulfate, and ASR [28]. |

| Carbon Footprint | Reduces CO₂ emissions by lowering clinker factor [27]. | Utilizes agricultural waste; significantly reduces cement demand and associated CO₂ [28]. |

| Optimal Replacement Level | 15-30% in ternary/blended systems [27]. | 10-30% as cement replacement [28]; 10-50% as sand replacement [10]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for replicating the experimental work or formulating these advanced cementitious mixes in a research setting.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Mix Design | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | Hydraulic addition; enhances long-term strength and refines microstructure via CSH formation [27]. | Verify fineness and chemical composition per relevant standards (e.g., EN 197-1). |

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) | Highly reactive pozzolan; reacts with portlandite to enhance density and strength [28] [10]. | Amorphous content is critical; controlled burning at ~600°C is recommended [10]. |

| Fly Ash (Class F) | Pozzolanic addition; contributes to long-term strength and refines pore structure [27]. | Low calcium content; ensures compliance with ASTM C618. |

| Alkaline Activator (NaOH/Na₂SiO₃) | Activates geopolymerization in aluminosilicate precursors like RHA and fly ash [29] [24] [30]. | Molarity (e.g., 4M-12M NaOH) and silicate modulus are key optimization parameters [30]. |

| Metakaolin | High-reactivity aluminosilicate precursor for geopolymers [29]. | Used in ternary geopolymer systems with RHA [29]. |

| Bauxite | Aluminosilicate source in alkali-activated composites [24]. | Blended with RHA and GGBS to form quaternary AAC systems [24]. |

| Zirconia (ZrO₂) | Nano-filler for cement; provides micro-filling, nucleation, and enhances chemical resistance [10]. | Used in low percentages (1-5%) as a partial cement replacement [10]. |

| Superplasticizer | Water-reducing admixture; maintains workability at low water/cementitious ratios. | Essential for mixes with high SCM content or low water demand. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Long-Term Performance of Ternary Blended Mortars

This methodology is designed to evaluate the durability and microstructural development of mortars under real-world exposure conditions [27].

- Materials and Mix Proportions: Prepare binders according to Table 1. A typical ternary blend, such as "SF," consists of 70% CEM I 42.5 R, 15% GGBS, and 15% fly ash. Use standard sand conforming to EN 196-1.

- Sample Preparation and Curing: Cast mortar prisms (e.g., 40x40x160 mm). Initially moist-cure for 24 hours, then demold and cure in water until 28 days of age.

- Exposure Conditions: Transfer the samples to an in-situ exposure station simulating a specific environment, such as an underground garage (corresponding to exposure class XC3 per Eurocode 2). This environment typically has moderate CO₂ concentrations and humidity variations.

- Testing and Characterization: Perform tests at intervals (e.g., 28, 90, 250 days).

- Compressive and Flexural Strength: Conduct mechanical tests according to EN 196-1.

- Microstructural Analysis: Use Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) to analyze pore structure and distribution.

- Durability Tests: Measure water absorption, diffusion coefficient, and carbonation depth [27].

Protocol 2: Optimization of RHA-based Alkali-Activated Composites

This protocol focuses on the mix design, experimental testing, and optimization of quaternary AAC systems [24].

- Mixture Proportioning: Develop multiple mixes with varying proportions of RHA, bauxite, GGBS, alkali activators, and water. A Central Composite Design (CCD) can be used to structure the experimental runs.

- Mixing and Curing: Dry-mix all solid precursors thoroughly. Add the alkaline activator solution and mix until homogeneous. Cast samples into cubes (e.g., 50x50x50 mm). Employ two curing regimes: oven curing (e.g., 60-80°C for 24-48 hours) followed by ambient curing, and full ambient temperature curing.

- Compressive Strength Testing: Test the specimens at specified ages (e.g., 7, 14, 28 days) using a compression testing machine, following relevant standards (e.g., BS EN).

- Regression Analysis and Optimization: Use software like MATLAB to perform regression analysis on the experimental data. Generate a model to predict compressive strength as a function of all input variables. Determine the optimal mix proportions that maximize strength.

- Microstructural Validation: Analyze samples from the optimal mix using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) to study gel formation, elemental composition, and phase identification [24].

Protocol 3: Compressive Strength Evaluation with Machine Learning Prediction

This protocol integrates experimental material science with advanced data modeling for property prediction [10].

- Mix Design and Sample Preparation: Proportion mortars at a 1:3 (binder:sand) ratio with a constant water-to-cement ratio (e.g., 0.50). Incorporate zirconia (1-5% by cement mass) and RHA (10-50% by sand mass). Cast cubes (70.6 mm) and cure in water.

- Testing Schedule: Test compressive strength at multiple ages (3, 7, 14, 28, and 56 days) per standards like IS 516:2018.

- Machine Learning Modeling: Compile a dataset of mix proportions, curing age, and compressive strength. Partition data into training and test sets. Train multiple ensemble models (e.g., CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest) using k-fold cross-validation. Evaluate models based on R² score and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Explainable AI Analysis: Use feature importance analysis (e.g., SHAP) to identify the most influential parameters (e.g., curing age, RHA content, zirconia content) on the compressive strength [10].

Visualizing Experimental and Analytical Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and computational workflow for developing and optimizing advanced mortar mixes, as exemplified in the cited studies.

This comparison guide synthesizes experimental data to objectively evaluate the performance of GGBS and RHA in various mortar mix designs. Key findings indicate that while binary mixes provide a solid foundation for improvement, ternary and quaternary systems often deliver superior performance due to synergistic effects. GGBS excels in long-term microstructural refinement and durability in blended cements, whereas RHA offers exceptional pozzolanic reactivity and strength enhancement, particularly in geopolymer and alkali-activated systems. The choice of an optimal precursor ratio is highly dependent on the target application, performance requirements, and sustainability goals. For biomedical research applications requiring material consistency and specific surface properties, the enhanced density and refined microstructure of ternary GGBS-fly ash mixes or optimized RHA-based AACs present promising avenues for further investigation.

The development of sustainable construction materials is a critical pursuit in modern materials science, driven by the need to mitigate the significant environmental impact of ordinary Portland cement (OPC) production [31]. Alkali-activated materials (AAMs) and geopolymers have emerged as promising alternatives, offering superior mechanical properties and the potential to utilize industrial and agricultural waste products [31] [32]. The performance of these materials is profoundly influenced by the type and characteristics of the alkaline activators used. This guide provides a detailed comparison of conventional activators against an innovative alternative—sodium silicate synthesized from rice husk ash (RHA)—with a specific focus on molarity effects and synthesis protocols. While the primary data is derived from construction materials research, the fundamental chemical principles and material properties discussed provide valuable insights for researchers exploring similar alkali-activated systems in biomedical applications, such as the development of bioactive cements or bone scaffolds, where control over mechanical strength, porosity, and chemical durability is paramount.

Alkaline Activators in Context: Conventional vs. RHA-Derived Solutions

Alkaline activators are strong basic solutions that dissolve silicon (Si) and aluminum (Al) species from precursor materials, initiating a polymerization process that results in a hardened binder [31] [5]. The most common activators include sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (KOH), and sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃, also known as waterglass) [31]. The combination of sodium silicate and sodium hydroxide is particularly effective, as it provides the necessary alkalinity and additional soluble silica, leading to the formation of a denser microstructure [5].

Conventional sodium silicate is typically produced from quartz sand and sodium carbonate at temperatures around 1400°C, an energy-intensive process with a high carbon footprint [33] [34]. In contrast, sodium silicate derived from Rice Husk Ash (RHA) offers a sustainable and often more economical alternative. RHA is an agricultural waste product containing a high percentage of silica (often over 90-95%) [33] [35]. Using RHA as a silica source for activator synthesis leverages a widely available waste material, reduces energy consumption, and creates a closed-loop system for agricultural by-products.

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional and RHA-Derived Sodium Silicate Production

| Feature | Conventional Sodium Silicate | RHA-Derived Sodium Silicate |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Silica Source | Quartz sand [33] | Rice Husk Ash (RHA) [33] [34] |

| Typical Synthesis Process | Fusion with Na₂CO₃ at ~1400°C [33] [34] | Fusion or reflux with NaOH at lower temperatures (e.g., 90-1500°C) [33] [36] |

| Environmental Impact | High energy consumption, high CO₂ emissions [34] | Utilizes agricultural waste, lower processing energy [34] |

| Key Advantage | Established, consistent industrial production | Sustainable, cost-effective, and customizable synthesis |

Synthesis Protocols for Sodium Silicate from RHA

Two primary methods for synthesizing sodium silicate from RHA are documented in the literature: a reflux method performed at atmospheric pressure and a high-temperature fusion method.

Reflux Method for Sodium Silicate Synthesis

This method is suitable for producing a sodium silicate solution under milder conditions [33].

- Material Preparation: Obtain white RHA, typically produced by burning rice husks at controlled temperatures (e.g., 600°C), which results in high silica content and desirable reactivity [33] [5].

- Dissolution: The RHA is dissolved in a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. A common ratio is 100 grams of RHA to 600 mL of NaOH solution (a 1:6 w/v ratio) [33].

- Heating and Stirring: The mixture is heated to 90°C for 1 hour under reflux conditions with constant stirring (e.g., at 1100 rpm) to facilitate silica dissolution [33].

- Filtration: The resulting solution is filtered to remove any unreacted residues or impurities, yielding a sodium silicate solution [33].

High-Temperature Fusion Method

This traditional method involves solid-state reaction at high temperatures and can be adapted using different sodium sources [36].

- Mixing: RHA is thoroughly mixed with a solid alkali source. This can be:

- Fusion: The mixture is heated to a high temperature, typically between 1200°C and 1500°C, for 2 to 4 hours to form solid sodium silicate [36].

- Dissolution: The fused product is dissolved in hot water (90-150°C) to create an aqueous sodium silicate solution. A typical w/w ratio of sodium silicate to water is between 1:10 and 1:20 [36].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps for both synthesis methods:

Performance Comparison: Molarity, Mechanical Properties, and Microstructure

The molarity of the alkaline activator is a critical factor that directly influences the dissolution of precursor materials, the geopolymerization reaction kinetics, and the final properties of the hardened matrix.

Effect on Compressive Strength

The data indicates that an optimal molarity exists for maximizing compressive strength, beyond which performance may decline.

- RHA-derived Sodium Silicate with Fly Ash: A study using RHA-derived sodium silicate with fly ash found that a combination of 10M NaOH and sodium silicate yielded the highest compressive strength, achieving a 16.21% increase. Conversely, increasing molarity to 12M led to a 13.23% decrease in strength [33].

- GGBS-RHA Geopolymer Concrete: In systems combining Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) and RHA, a molarity of 12M NaOH was identified as optimal. One study on lightweight geopolymer concrete reported that a mix with 100% GGBS and 12M NaOH (12G) demonstrated the best performance, retaining 86.4% to 91.4% of its compressive strength after six months of exposure to aggressive chemical environments [5].

- Conventional Activators in One-Part Systems: Research on one-part alkali-activated materials, which use solid activators, found that an optimal ternary activator blend (with a 6:3:1 ratio of Na-silicate: Na-hydroxide: Na-carbonate) achieved a compressive strength of 47 MPa [31].

Table 2: Effect of Activator Molarity on Compressive Strength in Different Systems

| Binder System | Activator Type | NaOH Molarity | Compressive Strength Performance | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fly Ash-based Geopolymer | RHA-derived Na₂SiO₃ + NaOH | 10 M | Highest strength, 16.21% increase | [33] |

| Fly Ash-based Geopolymer | RHA-derived Na₂SiO₃ + NaOH | 12 M | Reduced strength, 13.23% decrease | [33] |

| GGBS-RHA Geopolymer Concrete | Commercial Na₂SiO₃ + NaOH | 12 M | Best performance, >85% residual strength after chemical exposure | [5] |

| One-Part Alkali-Activated Slag | Ternary Solid Activator (Na-silicate:hydroxide:carbonate) | N/A (Solid blend) | 47 MPa, 80% lower CO₂ vs. OPC | [31] |

Microstructural Development

The molarity of the activator and the source of silicate significantly impact the microstructural properties of the final material.

- Low Molarity (e.g., 8M): Often results in insufficient dissolution of the precursor materials, leading to a less dense microstructure with higher porosity and, consequently, lower strength [33] [5].

- Optimal Molarity (e.g., 10-12M): Provides adequate alkalinity for effective dissolution of Si and Al species, promoting the formation of a dense and compact matrix. The reaction products in GGBS-RHA systems, such as calcium-(sodium)-alumino-silicate-hydrate (C-(N)-A-S-H) gel, contribute to this dense microstructure, which enhances durability and mechanical strength [31] [5].

- Excessive Molarity (e.g., >12M): Can lead to overly rapid setting and the potential for microcracking, which compromises the structural integrity and results in reduced strength, as observed in the fly ash system with 12M NaOH [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Alkali-Activation Research

| Item | Function in Research | Typical Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) | Primary silica source for sustainable activator synthesis; can also be used as a solid precursor. | White ash from controlled burning (~600°C) is preferred for high reactivity and amorphous silica content [33] [5]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Provides high alkalinity to dissolve precursors; used in synthesis of RHA-based silicate and as a co-activator. | Available in pellet or flake form; high purity (e.g., 98-99%) is recommended for consistent results [33] [5]. |

| Sodium Silicate (Na₂SiO₃) | Serves as a source of soluble silica for the formation of aluminosilicate gels; the benchmark for comparison. | Commercial "waterglass"; characterized by its SiO₂:Na₂O weight ratio (e.g., 2.0 to 3.2) [37]. |

| Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | Calcium-rich precursor that enhances early strength and forms C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels. | Off-white powder; specific gravity ~2.8 [5]. |

| Fly Ash | Aluminosilicate-rich precursor, a common base for geopolymers. | Class C or F according to ASTM C618 [31] [33]. |

| Trona | Sodium source (sodium carbonate-sodium bicarbonate) for the fusion synthesis of sodium silicate. | Can be a more economical alternative to pure sodium carbonate [36]. |

| Superplasticizer | To improve workability of fresh mixes without adding excess water. | Naphthalene-based superplasticizers are commonly used in geopolymer systems [5]. |

The choice of alkaline activator and its molarity is a fundamental determinant in the performance of alkali-activated materials. RHA-derived sodium silicate presents a scientifically validated and environmentally superior alternative to conventional waterglass. The experimental data consistently shows that an optimal molarity exists—often between 10M and 12M for NaOH—which maximizes compressive strength and microstructural density. While this guide is based on research for construction applications, the principles of activator synthesis, molarity optimization, and their impact on the mechanical and microstructural properties of the final product are directly transferable to the design and development of advanced materials in other fields, including biomedical research. The ability to fine-tune these parameters allows researchers to engineer materials with specific strength, porosity, and chemical resistance profiles to meet diverse application needs.

The performance of cementitious materials in biomedical applications, such as bone cements, dental restorations, and drug delivery scaffolds, is critically dependent on their mechanical integrity, chemical durability, and setting behavior. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two principal material systems: Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS)-based binders and Rice Husk Ash (RHA)-incorporated mixes. The selection and optimization of process parameters—curing regimes, water-to-binder (w/b) ratio, and alkali-to-precursor (A/P) ratio—directly govern the reaction kinetics, microstructure development, and final properties of these materials. GGBS, an industrial by-product, offers high strength and rapid setting, while RHA, an agricultural waste, provides enhanced pozzolanic reactivity and sustainability. Understanding the influence of these parameters is essential for tailoring material properties to meet the stringent requirements of biomedical applications, where performance and biocompatibility are paramount.

Material Composition and Property Comparison

The fundamental differences in the chemical and physical properties of GGBS and RHA direct their performance in cement mortar mixes. The table below summarizes their characteristic compositions and primary roles in mortar formulations.

Table 1: Composition and Properties of GGBS and RHA

| Property | GGBS (Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag) | RHA (Rice Husk Ash) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Oxide Composition | High in CaO (36.81%), SiO₂ (34.80%), and Al₂O₃ (15.78%) [38] | Very high in SiO₂ (91.7%), with minor Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃, and K₂O [10] |

| Chemical Role | Cementitious; forms C-A-S-H and C-S-H gels upon activation [39] [40] | Pozzolanic; reacts with Ca(OH)₂ to form additional C-S-H gel [41] [10] |

| Physical Role | Contributes to early strength and dense microstructure [40] | Acts as a micro-filler and refines pore structure [41] [10] |

| Specific Gravity | 2.88 [38] | 2.2 [10] to 2.3 [5] |

| Optimal Replacement Level | Can be used as a 100% binder or a major component [42] [40] | Typically ~10% of the binder for enhanced strength and durability [41] [10] |

The performance of mortars incorporating these materials is a direct result of their distinct compositions. The following table compares key performance metrics of GGBS-dominant and RHA-incorporated mixes based on experimental data.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GGBS vs. RHA-Incorporated Mixes

| Performance Metric | GGBS-Based Systems | RHA-Incorporated Systems | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal Compressive Strength | ~175 MPa (in ultra-high performance formulations) [43] | ~33.8% increase over control (with 3% ZrO₂ and 10% RHA) [10] | GGBS systems achieve very high absolute strength. RHA provides significant relative enhancement. |

| Optimal Alkali-to-Precursor (A/P) Ratio | 0.4 (for workability and strength) [7] | 0.4 (in GGBS-RHA systems) [7] | A/P ratio is critical for geopolymerization; 0.4 is a common optimum. |

| Residual Compressive Strength in Aggressive Environments | N/A | 86.4% (in 3% HCl), 90.6% (in 5% MgSO₄), 91.4% (in 3.5% NaCl) [5] | Demonstrates excellent durability of RHA-GGBS blends in chemically harsh conditions, relevant for biomedical implants. |

| Effect of High Temperature (≥600°C) | Significant strength loss due to paste decomposition and microcracking [42] | N/A | Critical for fire resistance of structures; GGBS mortar strength is maintained up to ~300°C [42]. |

Influence of Critical Process Parameters

Curing Regimes

The curing environment profoundly impacts the hydration and geopolymerization processes, dictating the final material's microstructure and strength.

- Ambient Curing vs. Sealed Curing: Research shows that sealed curing, which prevents moisture loss, results in a higher presence of Na⁺ in the matrix and promotes a more complete reaction compared to unsealed ambient curing. This leads to the formation of a more robust microstructure with superior compressive strength over time [39].

- Heat Curing: While heat curing (e.g., at 60-85°C) can accelerate strength development in some geopolymer systems, it is often impractical for in-situ applications and can increase production costs. The incorporation of calcium-rich materials like GGBS facilitates effective ambient temperature curing, which is vital for wider application, including certain biomedical settings [40].

- Curing in Biomedical Context: For biomedical materials, sealed curing that ensures a stable, humid environment may be critical to prevent premature drying and cracking, which could compromise the integrity of a bone cement or a drug-eluting implant.

Water-to-Binder (w/b) Ratio

The w/b ratio is a critical parameter controlling workability, porosity, and ultimate strength.

- Strength and Workability Trade-off: A lower w/b ratio typically yields a denser microstructure and higher compressive strength. However, an excessively low w/b can compromise workability, making the mix difficult to handle and place [42] [43]. A w/b ratio of 0.50 has been identified as a balanced point for GGBS-based geopolymer concrete, providing adequate workability without severely sacrificing strength [7].

- Weight Loss at High Temperatures: Studies on cement mortar modified with GGBFS show that higher w/b ratios are associated with increased weight loss upon exposure to elevated temperatures. This is attributed to the higher volume of evaporable water, which escapes upon heating, potentially increasing porosity and compromising the material's integrity [42].

- Biomedical Implications: In preparing injectable bone cements, a low w/b ratio is desirable for high strength, but the ratio must be high enough to ensure injectability. Furthermore, a lower porosity achieved through a low w/b ratio can enhance the material's resistance to bodily fluids.

Alkali-to-Precursor (A/P) Ratio

In alkali-activated systems, the A/P ratio determines the availability of activators for dissolving the aluminosilicate precursors.

- Optimum for Geopolymerization: An A/P ratio of 0.4 is frequently reported as optimal for GGBS-based geopolymers activated with a combination of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate. At this ratio, there is sufficient alkali to initiate and sustain the geopolymerization reaction without an excessive amount that could lead to efflorescence or brittle behavior [7].

- Effect on Fresh and Hardened Properties: The A/P ratio directly influences the workability of the fresh mix and the development of mechanical strength. A study on GGBS-based geopolymer concrete found that UCS and tensile strength peaked at an A/P ratio of 0.4, with workability being suitable at this level [7].

Experimental Protocols for Performance Evaluation

Protocol 1: Compressive Strength Development of RHA-GGBS Geopolymer

This protocol is adapted from studies optimizing alkali-activated RHA-GGBS cementitious materials [41] [7].

Material Preparation:

- Precursors: Use GGBS conforming to relevant standards (e.g., BS EN 15167-1:2006). RHA should be produced by controlled calcination of rice husk at 600-700°C for 2 hours to ensure an amorphous silica structure [41] [7].

- Alkaline Activator: Prepare a sodium silicate alternative (SSA) solution by dissolving RHA in a sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. Alternatively, use a combination of commercial sodium silicate (Na₂SiO₃) and a 10M NaOH solution. The ratio of Na₂SiO₃ to NaOH is often 1:1 by mass [7].

- Aggregates: Use standard sand or other fine aggregates as per the experimental requirement.

Mix Proportions and Specimen Casting:

- The binder should consist of 80% GGBS and 20% RHA by mass [5].

- Maintain an Alkali-to-Precursor (A/P) ratio of 0.4 and a Water-to-Binder (w/b) ratio of 0.50 [7].

- Mix dry precursors and aggregates uniformly. Add the alkaline activator solution and mix to achieve a homogeneous paste.

- Cast mortar into cube molds (e.g., 50mm or 70.6mm cubes) in layers, compacting each layer on a vibrating table.

Curing and Testing:

- Cure the specimens in a sealed condition at ambient temperature (e.g., 23±2°C) to prevent moisture loss [39].

- Demold after 24 hours and continue sealed curing until the testing age.

- Test the compressive strength at ages of 3, 7, 14, 28, and 56 days using a universal testing machine, following relevant standards (e.g., IS 516:2018) [10].

Protocol 2: Durability Evaluation in Aggressive Environments

This protocol assesses resistance to chemical attacks, crucial for biomedical implants, based on research into GGBS-RHA geopolymer concrete [5].

Specimen Preparation:

- Prepare geopolymer mortar specimens as described in Protocol 1, with a NaOH molarity of 12M.

- Cure specimens sealed at ambient temperature for 28 days.

Exposure to Aggressive Media:

- After 28 days, immerse the specimens in simulated chemical solutions: 3% HCl (simulating acidic environments), 5% MgSO₄ (simulating sulfate attack), and 3.5% NaCl (simulating saline body fluids).

- Maintain a constant temperature and solution concentration for a prolonged period, e.g., 6 months [5].

Post-Exposure Analysis:

- Residual Compressive Strength: After exposure, test the specimens for compressive strength and compare the results with control specimens cured in water.

- Microstructural Analysis: Perform Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDAX) on exposed samples to observe microstructural changes and elemental composition, identifying the formation of dense gels (C-A-S-H, N-A-S-H) or deleterious products [5].

Process Parameter Relationships and Material Properties

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the critical process parameters and their combined influence on the microstructure and final properties of the cement mortar.

Diagram Title: Parameter Impact on Mortar Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions for developing and testing GGBS and RHA-incorporated cement mortars.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research | Specification Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) | Primary cementitious precursor; provides calcium for C-S-H and C-A-S-H gel formation. | Specific gravity: ~2.88; CaO content: ~37% [38]. Conform to IS 12089 or BS EN 15167-1. |

| Rice Husk Ash (RHA) | Pozzolanic material and micro-filler; provides reactive silica for secondary C-S-H formation. | High amorphous SiO₂ content (>90%); specific gravity: ~2.2 [10]. Produced at 600-700°C. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline activator; dissolves Si and Al from precursors to initiate geopolymerization. | Purity: 98% pellets; commonly used as 8-16M solutions [38] [5]. |

| Sodium Silicate (Na₂SiO₃) | Alkaline activator; provides soluble silica for gel formation, enhancing density and strength. | Often used with NaOH in a mass ratio (SS:SH) of 1:1 to 2.5:1 [7] [40]. |

| Superplasticizer (PCE-based) | Water-reducing admixture; improves workability of low w/b ratio mixes without sacrificing strength. | Dosage typically 1-2% by binder mass; beyond saturation can cause segregation [42]. |

| Lightweight Expanded Clay Aggregate (LECA) | Artificial lightweight aggregate; reduces density and provides internal curing in composites. | 35% replacement of conventional coarse aggregate [5]. |

The systematic comparison of GGBS and RHA-incorporated cement mortars reveals a clear trade-off between absolute mechanical performance and enhancement through pozzolanic activity. GGBS-based systems are capable of achieving ultra-high strength, making them suitable for load-bearing biomedical applications. In contrast, RHA incorporation significantly improves durability and chemical resistance, which is critical for implants exposed to bodily fluids. The optimization of critical process parameters is non-negotiable; a w/b ratio of 0.50 and an A/P ratio of 0.4 under sealed, ambient curing conditions consistently emerge as a robust starting point for developing high-performance mixes. For biomedical research, future work should focus on correlating these physicochemical parameters with biological responses, such as biointegration and cytokine expression, to truly advance the field of cementitious materials for health.