Navigating Ethical Frontiers: A Comprehensive Guide to Biomedical Engineering Society Codes of Ethics

This article provides a detailed examination of the ethical frameworks established by leading biomedical engineering societies, including the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) and the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society...

Navigating Ethical Frontiers: A Comprehensive Guide to Biomedical Engineering Society Codes of Ethics

Abstract

This article provides a detailed examination of the ethical frameworks established by leading biomedical engineering societies, including the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) and the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational ethical principles, their practical application in research and development, strategies for resolving complex ethical dilemmas, and the systems in place for professional validation and compliance. By integrating theoretical guidelines with real-world case studies and professional standards, this overview serves as an essential resource for upholding integrity and advancing public health in the rapidly evolving field of biomedical engineering.

The Bedrock of Integrity: Core Principles in Biomedical Engineering Ethics

The field of biomedical engineering stands at the intersection of technological innovation, human health, and ethical responsibility. Society codes of ethics serve as the foundational frameworks that translate abstract moral principles into actionable professional standards for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. These codes establish the professional mandate—the collective commitment to conduct that transcends legal requirements and embraces the broader social and ethical implications of biomedical innovation. In an era of rapid technological advancement, with emerging areas such as CRISPR genome editing, brain-computer interfaces, and artificial intelligence in medicine, these ethical codes provide the critical guidance necessary to navigate complex dilemmas while maintaining public trust [1].

The fundamental purpose of these codes is to articulate the profession's core values and expectations, creating a shared understanding of responsible conduct across disciplines and institutions. For biomedical engineers, whose work directly impacts human health and wellbeing, this ethical framework is not supplementary but central to professional identity. As noted in critical analyses of the field, "Biomedical engineering is responsible for many of the dramatic advances in modern medicine. This has resulted in improved medical care and better quality of life for patients. However, biomedical technology has also contributed to new ethical dilemmas and has challenged some of our moral values" [2]. Society codes of ethics serve as the essential compass for navigating these dilemmas, providing both direction for action and accountability mechanisms when standards are breached.

Comparative Analysis of Biomedical Engineering Society Codes

Core Ethical Principles and Their Applications

Biomedical engineering codes of ethics across professional societies share common foundational principles while emphasizing different aspects based on their organizational focus and membership. These principles provide the philosophical underpinnings for professional conduct and decision-making frameworks.

Beneficence and Non-maleficence represent complementary duties toward patients and research subjects. The principle of beneficence requires biomedical engineers to actively promote patient wellbeing through their designs, devices, and technologies, while non-maleficence demands the avoidance of harm through rigorous testing, risk assessment, and safety protocols [3]. This includes "designing, developing, and maintaining medical devices and technologies that are safe, reliable, and effective for patient use" through "rigorous testing and validation of medical devices and technologies to minimize the risk of adverse events" [3].

Respect for Autonomy acknowledges the right of patients and research subjects to make informed decisions about their care and participation. This principle requires biomedical engineers to ensure patients receive "clear and comprehensive information about medical devices and technologies used in their care to enable them to make informed decisions" [3]. This extends to respecting cultural, social, and individual factors that may influence patient autonomy and implementing appropriate safeguards for those with diminished capacity [3].

Justice in biomedical engineering ethics encompasses both distributive justice (fair allocation of resources and technologies) and social justice (addressing healthcare disparities). The principle demands that "biomedical engineers ensure fair and equitable access to healthcare technologies and services, regardless of a patient's socioeconomic status or background" [3]. This has become particularly salient during public health crises, as evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced difficult ethical decisions regarding "the allocation of medical devices, the responsibilities of science and technology, and the inadequacy of regulations and norms, which lack universality" [4].

Integrity and Honesty form the bedrock of professional relationships and scientific enterprise. These principles require truthfulness and transparency in all professional activities, including "accurately reporting research findings, disclosing potential conflicts of interest, and acknowledging the contributions of others" [3]. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) Code of Ethics specifically emphasizes "promoting transparency, implementing reporting systems for violations and establishing ethical decision-making models to standardize procedures" [5].

Comparative Table of Professional Society Codes

Table 1: Comparison of Ethical Principles Across Engineering Societies

| Ethical Principle | BMES | IEEE EMBS | NSPE | ASCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Welfare | Explicitly emphasized | Explicitly emphasized | Primary emphasis | Primary emphasis |

| Research Integrity | Required | Required through scientific integrity | Implied | Implied |

| Privacy & Confidentiality | Required | Explicit requirement for patient data | Not specified | Not specified |

| Environmental Responsibility | Not specified | Explicit requirement | Not specified | Explicitly emphasized |

| Conflict of Interest | Avoidance or disclosure required | Avoidance or disclosure required | Required | Required |

| Interdisciplinary Respect | Explicitly required | Explicitly required | Not specified | Emphasized for collaboration |

| Professional Competence | Required | Implied through research standards | Required | Required |

| Reporting Violations | Systems established | Not specified | Explicit mechanism | Explicit mechanism |

Note: BMES = Biomedical Engineering Society; IEEE EMBS = Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society; NSPE = National Society of Professional Engineers; ASCE = American Society of Civil Engineers. Data synthesized from multiple sources [5] [6] [7].

The comparative analysis reveals both universal principles and distinctive emphases across professional societies. While all major engineering codes prioritize public welfare, biomedical societies place particular emphasis on research integrity, privacy protection, and interdisciplinary collaboration—reflecting the unique challenges at the intersection of engineering, biology, and medicine. The IEEE EMBS code specifically addresses environmental responsibility, requiring members to "support the preservation of a healthy environment," while BMES emphasizes creating "a culture of knowledge exchange and mentorship" [6]. These nuances reflect how different engineering disciplines interpret and apply ethical principles within their specific professional contexts.

Implementation Framework for Ethical Decision-Making

Methodologies for Ethical Analysis and Application

Translating ethical principles into professional practice requires structured methodologies for analyzing and resolving dilemmas. Several established frameworks provide biomedical engineers with systematic approaches to ethical decision-making.

The Four Principles Approach provides a quadrant-based methodology that balances competing ethical demands through the principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice [3]. When facing an ethical dilemma, biomedical engineers using this framework would identify how each principle applies to the situation, determine where principles may conflict, and seek a resolution that respects all four principles to the greatest extent possible. This approach was developed specifically for biomedical ethics and has been widely adopted in healthcare settings.

Utilitarian Analysis applies a consequentialist framework to ethical dilemmas, seeking to maximize overall benefit and minimize harm. This methodology involves identifying all stakeholders who would be affected by a decision, calculating potential benefits and harms for each group, and selecting the course of action that produces the greatest net benefit [3]. During resource allocation decisions, such as those encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic, "utilitarianism, which focuses on maximizing overall utility or well-being, can be applied to biomedical engineering dilemmas to determine the course of action that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people" [3].

Deontological Frameworks emphasize adherence to moral duties and rules regardless of consequences. This approach involves identifying one's duties in a given situation (e.g., duty to protect patient safety, duty to maintain confidentiality, duty to be truthful) and selecting the course of action that best fulfills these obligations [3]. For biomedical engineers, this might mean upholding safety standards even when faced with pressure to accelerate product development timelines.

Casuistry or Case-Based Reasoning employs analogical thinking by comparing current ethical dilemmas with previously resolved cases [3]. This methodology involves identifying paradigmatic cases with established ethical consensus, noting relevant similarities and differences with the current situation, and determining whether the same ethical resolution should apply. This approach allows biomedical engineers to draw on established precedents while recognizing the unique aspects of each situation.

Ethical Decision-Making Workflow

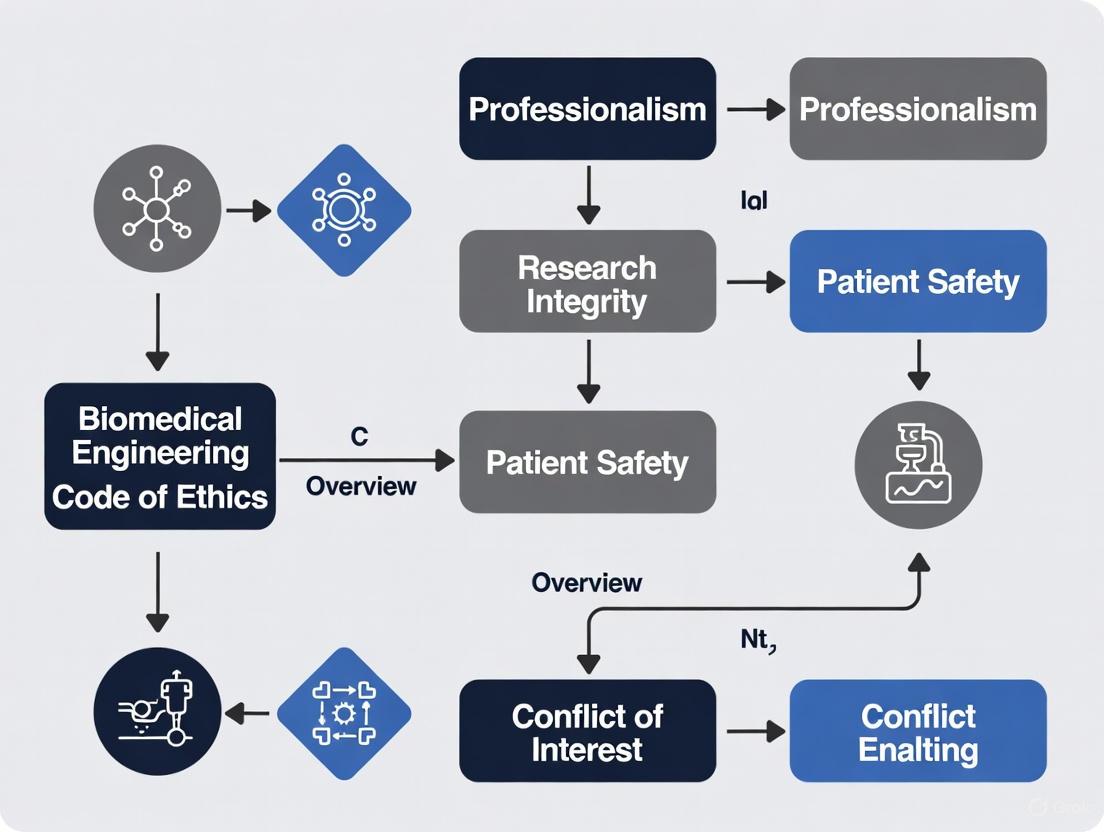

Diagram 1: Ethical Decision-Making Workflow. This diagram illustrates a systematic methodology for addressing ethical dilemmas in biomedical engineering practice and research.

The ethical decision-making workflow provides biomedical engineers with a structured process for navigating complex situations. This methodology begins with thorough fact-finding and stakeholder analysis, followed by the application of multiple ethical frameworks and consultation of relevant professional codes. After generating and evaluating alternatives, the engineer implements the chosen course of action with appropriate documentation and follow-up assessment. This systematic approach ensures consistent, transparent, and defensible ethical reasoning, particularly valuable in situations involving competing priorities or stakeholder interests.

Current Challenges and Special Considerations

Emerging Ethical Dilemmas in Biomedical Engineering Practice

Biomedical engineers today face novel ethical challenges that test the applicability and completeness of existing ethical codes. These emerging dilemmas require careful consideration and sometimes the evolution of ethical standards.

Resource Allocation and Triage Protocols became critically urgent during the COVID-19 pandemic, when biomedical engineers faced "the dilemma of identifying criteria for the allocation of medical devices" as healthcare systems were overwhelmed [4]. The pandemic revealed that "within a few weeks, the available resources (i.e., medical devices, doctors, nurses) proved to be insufficient to cover the care needs of the multitude of COVID-19 patients, beyond the ordinary needs of other patients" [4]. These situations forced difficult ethical choices between clinical criteria (prioritizing those with the greatest medical need) and utilitarian considerations (prioritizing those with the greatest likelihood of survival).

Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Medical Solutions emerged as an unregulated response to equipment shortages during the pandemic, creating new ethical concerns. The "rise of useless and potentially harmful DIY approaches to PPE and medical devices could have been easily avoided at the start of the pandemic by decision-makers initially consulting with domain experts, such as biomedical and clinical engineers" [4]. This phenomenon highlighted the tension between innovation and safety, as "although very admirable, this approach is not feasible in critical sectors such as medical devices or PPE, which require postgraduate education, years of experience and deep knowledge of relevant international standards and norms, in order to ensure appropriate levels of safety, efficacy and resilience" [4].

Dual-Use Dilemmas involve biomedical technologies developed for beneficial purposes that could be misused for harm. "In biomedical research, the dual-use dilemma is an ethical consideration regarding the potential misuse or abuse of certain biomedical technologies" [5]. For example, "research on a deadly virus such as H1N1 (swine flu) could potentially lead to advances in treatment, but it also poses risks if the dangerous pathogen gets into the wrong hands" [5]. Biomedical engineers must therefore "weigh the pros and cons of their research and seek to mitigate any misuse of dangerous substances by implementing strict security measures, ethical guidelines and oversight" [5].

Genome Editing and Enhancement Ethics represent frontier ethical challenges as technologies like CRISPR advance rapidly. Educational initiatives now prepare biomedical engineers to consider "the ethical ideas and problems" pertaining to "CRISPR and the ever-evolving field of genome engineering" [1]. These technologies raise fundamental questions about "the ownership and commercialization of organoids used in basic research" and the potential for non-therapeutic enhancements that could exacerbate social inequalities [1].

Research Reagents and Tools for Ethical Analysis

Table 2: Essential Methodologies for Ethical Analysis in Biomedical Engineering Research

| Methodology/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Four Principles Framework | Provides balanced ethical analysis through autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice | Clinical trials, device design, resource allocation decisions |

| Belmont Report Principles | Guides research ethics through respect for persons, beneficence, and justice | Human subjects research, study design, informed consent processes |

| Utilitarian Analysis | Maximizes overall benefit and minimizes harm | Public health interventions, resource allocation, policy development |

| Deontological Analysis | Focuses on moral duties and rules | Safety protocols, quality assurance, regulatory compliance |

| Casuistry (Case-Based Reasoning) | Applies precedents from established cases | Novel ethical dilemmas, institutional policy development |

| Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) | Provides independent ethical oversight | Research protocols involving human subjects, clinical investigations |

| Ethical Impact Assessment | Systematically evaluates potential ethical implications | New technology development, research program planning |

These methodologies serve as essential "research reagents" for ethical analysis, providing structured approaches to identifying, analyzing, and resolving ethical challenges in biomedical engineering. Unlike laboratory reagents, these are intellectual tools that enable systematic reasoning about moral questions. Their proper application requires both knowledge of the methodologies themselves and understanding of when each is most appropriately deployed.

Society codes of ethics in biomedical engineering represent more than static documents—they embody a dynamic professional mandate that evolves alongside technological capabilities and social expectations. These codes serve simultaneously as compass, contract, and covenant: guiding professional judgment, establishing standards for accountability, and affirming the profession's commitment to societal wellbeing. As biomedical engineering continues to advance into new frontiers—from neuroengineering to synthetic biology—these ethical frameworks will require continual refinement and interpretation to address emerging challenges.

The true measure of these ethical codes lies not merely in their formulation but in their integration into the daily practice of biomedical researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This requires both formal education, such as dedicated ethics courses that provide "the foundational knowledge the students need to become well-rounded, ethical engineers" [1], and organizational cultures that support ethical conduct through "reporting systems for violations and establishing ethical decision-making models to standardize procedures" [5]. Through this integration, biomedical engineers can fulfill their professional mandate: to harness technological innovation for human benefit while conscientiously navigating the ethical dimensions of their work.

The integration of ethical principles into biomedical engineering practice provides a crucial framework for navigating the complex moral landscape of healthcare technology development. As the field of biomedical engineering operates at the intersection of patient care and technological innovation, the adoption of a structured ethical approach becomes paramount for ensuring responsible research and development. The four principles of biomedical ethics—beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice—have emerged as cornerstones of ethical decision-making in healthcare contexts since their systematic articulation by Beauchamp and Childress in their seminal work, Principles of Biomedical Ethics [8]. These principles offer a comprehensive framework that guides professionals in balancing competing values and obligations when developing medical technologies and conducting research.

Within biomedical engineering, these principles transcend theoretical discourse to inform daily practice, institutional policies, and professional standards. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) and other professional organizations have codified expectations for ethical conduct that reflect these core principles [5]. More recently, the development of a formal "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" has created a symbolic counterpart to medicine's Hippocratic Oath, explicitly incorporating these principles into a ceremonial pledge for graduating engineers [9] [10]. This evolution underscores the growing recognition that ethical frameworks must be deeply embedded in the professional identity of biomedical engineers, whose decisions directly impact patient safety, healthcare efficacy, and the equitable distribution of medical resources.

The Four Ethical Principles: Foundations and Applications

Detailed Analysis of Core Principles

Beneficence

The principle of beneficence establishes a positive obligation for biomedical engineers to act in ways that promote the welfare and best interests of patients and other stakeholders. This principle requires more than merely avoiding harm; it demands active contribution to patient well-being through the design, development, and implementation of biomedical technologies [11] [12]. In practical terms, beneficence translates to creating medical devices and systems that actively improve health outcomes, enhance quality of life, and advance medical capabilities. For example, developing more effective diagnostic equipment, creating more responsive prosthetic limbs, or designing telemedicine platforms that expand access to care all represent applications of the beneficence principle.

The ethical commitment to beneficence requires biomedical engineers to prioritize projects and design choices that maximize potential benefits for end users. This involves not only technical excellence but also consideration of how technologies will integrate into clinical workflows and patient lives [5]. The principle acknowledges that biomedical engineering has a fundamental moral purpose: to apply engineering expertise toward improving human health. This positive duty distinguishes beneficence from the merely prohibitive nature of non-maleficence, establishing an affirmative ethical mandate for the profession [13].

Non-Maleficence

Non-maleficence, embodied by the maxim "first, do no harm" (primum non nocere), obligates biomedical engineers to refrain from causing harm or injury to patients through acts of commission or omission [8]. This principle finds practical application in rigorous risk assessment, comprehensive safety testing, and systematic error mitigation throughout the design and development process. The profound responsibility associated with non-maleficence in biomedical engineering is highlighted by historical cases where its violation led to tragic outcomes, such as the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine incidents, where design flaws and safety oversights resulted in patient fatalities [5].

The implementation of non-maleficence requires a proactive approach to identifying potential harms, including direct physical injuries, secondary complications, and more subtle psychological or social impacts. Biomedical engineers must establish robust quality control systems, implement fail-safe mechanisms, and conduct thorough failure mode analysis to satisfy their ethical duty of non-maleficence [5]. This principle also extends to considering potential misuse of technologies and implementing appropriate safeguards. In situations where some risk is unavoidable, non-maleficence requires careful weighing of potential harms against anticipated benefits, ensuring that risks are minimized and clearly communicated to users [8].

Autonomy

The principle of autonomy recognizes the right of individuals to make informed decisions about their own healthcare and participation in research [11]. This principle provides the ethical foundation for informed consent processes, truth-telling requirements, and respect for patient values and preferences. For biomedical engineers, supporting autonomy involves designing technologies that enhance rather than diminish patient self-determination, such as creating interfaces that provide clear information for decision-making or developing adjustable devices that accommodate individual preferences and needs [10].

The practical application of autonomy in biomedical engineering extends beyond device design to research practices and commercial interactions. Engineers must ensure that research participants receive complete and accurate information about procedures, risks, and benefits, and that their consent is voluntary and free from coercion [12]. This principle also demands transparency about device capabilities and limitations, avoiding deception or exaggeration that would undermine meaningful consumer choice. The growing emphasis on patient-centered design in medical technology reflects the increasing importance accorded to autonomy in biomedical engineering practice [13] [8].

Justice

The principle of justice requires the fair, equitable, and appropriate distribution of healthcare benefits and resources [8]. In biomedical engineering, this principle addresses concerns about accessibility, affordability, and the equitable distribution of technological innovations across diverse populations. Justice considerations prompt critical examination of how medical technologies might exacerbate or ameliorate existing healthcare disparities based on socioeconomic status, geographic location, race, ethnicity, or other factors [5].

The application of justice in biomedical engineering practice includes designing technologies with scalability and cost-effectiveness in mind, advocating for equitable access to medical innovations, and considering the needs of underserved populations during the research and development process [10]. This principle also encompasses fair subject selection in research, ensuring that participant burdens and benefits are distributed justly across communities. The growing emphasis on global health technology represents one response to justice concerns, focusing on developing appropriate, affordable technologies for resource-limited settings [14].

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles in Biomedical Engineering Practice

| Principle | Core Meaning | Primary Application in BME | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficence | Duty to promote well-being and act in patients' best interests | Developing technologies that actively improve health outcomes | Benefit-risk analysis, therapeutic efficacy, quality of life improvement |

| Non-maleficence | Obligation to avoid causing harm | Rigorous safety testing, risk assessment, and error mitigation | Failure mode analysis, safety standards, harm prevention |

| Autonomy | Respect for individuals' right to self-determination | Informed consent processes, user-controlled devices, transparent design | Truth-telling, informed choice, respect for patient values |

| Justice | Fair distribution of benefits and burdens | Equitable access to technology, inclusive design, fair subject selection | Healthcare disparities, affordability, accessibility |

Interrelationship and Balancing of Principles

The four ethical principles do not function in isolation but rather form an interconnected framework that must be applied collectively to address complex ethical challenges. In practice, principles often come into tension, requiring careful balancing. For example, the development of an innovative but expensive medical technology might promote beneficence for those who can access it while potentially conflicting with justice if it remains unavailable to underserved populations [8]. Similarly, a perfectly safe device (non-maleficence) might provide limited therapeutic benefit (beneficence), necessitating trade-offs between these principles.

The process of ethical decision-making in biomedical engineering typically involves identifying which principles are relevant to a particular situation, assessing their relative weight in that context, and seeking solutions that honor the most compelling ethical claims [8]. This balancing process requires practical wisdom and moral reasoning rather than mechanical application of rules. The "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" implicitly acknowledges this interplay by structuring its commitments hierarchically, with safety and well-being (encompassing non-maleficence and beneficence) receiving priority, followed by other commitments that reflect autonomy and justice [10].

Diagram 1: Ethical Decision Framework in Biomedical Engineering. This diagram illustrates how the four core principles inform the ethical decision-making process in biomedical engineering, requiring balancing and application through specific procedures to achieve ethical practice.

Implementation in Biomedical Engineering Practice

Institutionalization Through Codes and Pledges

The ethical principles of beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice have been institutionalized within biomedical engineering through various formal mechanisms, including professional codes of ethics and, more recently, ceremonial pledges. The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) Code of Ethics embodies these principles by outlining norms and obligations that "fulfill a biomedical engineer's commitment to honesty and conscientiousness in scientific inquiry and technology development, and to advancing public health" [5]. This code provides concrete guidance for professional conduct that reflects the underlying principles, such as prioritizing patient safety (non-maleficence) and maintaining research integrity (justice).

The recently developed "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" represents a significant advancement in professional identity formation, creating a symbolic counterpart to medicine's Hippocratic Oath that is specifically tailored to biomedical engineering [9]. This pledge explicitly incorporates the four principles through ten specific commitments, with the first commitment prioritizing "safety, health, and well-being" (beneficence and non-maleficence) and subsequent commitments addressing autonomy (ensuring "autonomy and dignity"), justice (non-discrimination, environmental sustainability, universal health coverage), and related ethical concerns [10]. The structured hierarchy of these commitments provides practical guidance for resolving conflicts between principles, with safety and well-being receiving priority.

Practical Application in Research and Development

The implementation of ethical principles extends beyond formal documents to daily practice in biomedical engineering research and development. This practical application occurs through several key processes:

Risk-Benefit Analysis: Systematic evaluation of potential harms against anticipated benefits represents a primary methodology for balancing beneficence and non-maleficence [10]. This analytical process requires quantitative assessment where possible, complemented by qualitative consideration of values and preferences. The Nuremberg Code established that "the degree of risk to be taken should never exceed that determined by the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved by the experiment" [10], establishing a foundational approach for ethical risk-benefit assessment in biomedical engineering.

Informed Consent Protocols: Implementing autonomy requires developing comprehensive informed consent processes that ensure research participants and patients understand procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives [12]. For biomedical engineers, this extends to creating clear documentation for clinical trials, designing intuitive device interfaces that support user understanding, and ensuring transparency about device capabilities and limitations.

Inclusive Design Practices: Applying the principle of justice involves actively considering diverse user needs during the design process to avoid technologies that disproportionately benefit specific populations while excluding others [5]. This includes addressing physical variability through ergonomic design, accommodating different technical literacies through intuitive interfaces, and considering economic constraints through appropriate technology development.

Ethical Oversight Mechanisms: Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) provide formal oversight for research involving human subjects, evaluating proposals for ethical considerations, scientific merit, and regulatory compliance [12]. These boards assess whether research protocols adequately address all four ethical principles, particularly through risk minimization (non-maleficence), informed consent (autonomy), fair subject selection (justice), and potential benefits (beneficence).

Table 2: Ethical Assessment Framework for Biomedical Engineering Research

| Research Phase | Primary Ethical Considerations | Application Methods | Documentation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Development | Social value, scientific validity | Literature review, stakeholder consultation | Research protocol, rationale for approach |

| Risk-Benefit Assessment | Non-maleficence, beneficence | Systematic risk identification, benefit analysis | Risk categorization, mitigation strategies |

| Participant Selection | Justice, fairness | Inclusion/exclusion criteria, recruitment plan | Demographic representation plan |

| Informed Consent | Autonomy, respect for persons | Consent form development, process design | Documentation of consent process |

| Ongoing Monitoring | Non-maleficence, beneficence | Data safety monitoring, interim analysis | Safety reports, protocol modifications |

Case Studies Illustrating Ethical Challenges

Real-world cases provide valuable insights into the critical importance of rigorously applying ethical principles in biomedical engineering:

Therac-25 Radiation Therapy Incidents: This case represents a profound failure of non-maleficence, where software design flaws and inadequate safety engineering resulted in fatal radiation overdoses to patients [5]. The incidents highlighted the essential responsibility of biomedical engineers to implement comprehensive safety measures, including fail-safe mechanisms, rigorous testing protocols, and thorough investigation of error reports. The tragedy underscored how technological complexity creates ethical obligations for engineers to anticipate and prevent potential harms through defensive design strategies.

Bjork-Shiley Heart Valve: This case involved a prosthetic heart valve with a design flaw that led to strut failure and catastrophic outcomes for patients [5]. Despite early indications of problems, the devices remained on the market, representing failures in both non-maleficence (continuing to expose patients to known risks) and autonomy (withholding information about device performance that would have influenced patient and surgeon decisions). The case illustrates the ethical imperative for transparent reporting of device performance and prompt response to safety concerns.

Theranos Blood Testing Technology: This case involved deceptive claims about the capabilities of blood testing technology, representing fundamental violations of autonomy (through deception that undermined meaningful consent) and justice (by potentially exacerbating health disparities through inaccurate results) [10]. The case highlights the ethical responsibility of biomedical engineers to maintain integrity in technology development, avoid exaggeration of capabilities, and ensure transparent validation of performance claims.

Emerging Challenges and Evolving Applications

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The rapid integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into biomedical engineering presents novel ethical challenges that require both application and potential adaptation of the four principles framework. The "black box" nature of some AI systems creates tension with autonomy, as limited explainability may undermine meaningful informed consent and patient understanding [15]. Similarly, AI systems trained on biased datasets may perpetuate or amplify healthcare disparities, creating justice concerns that must be addressed through careful attention to data sourcing and algorithm design [15].

The principle of non-maleficence takes on new dimensions in AI-enabled medical devices, where harms may emerge from unexpected system behaviors, adversarial attacks, or distributional shifts in input data. Beneficence requires that AI systems demonstrably improve upon existing approaches rather than simply automating suboptimal processes. The European High Level Expert Group on AI and other regulatory bodies have responded to these challenges by proposing frameworks that build upon the traditional principles while adding new dimensions such as explicability, reflecting the unique characteristics of AI systems [15].

Global Health and Resource Constraints

Biomedical engineering in global health contexts intensifies concerns about justice, as resource constraints may limit access to medical technologies that are routinely available in high-income settings. This challenge has prompted growing interest in "frugal innovation" approaches that prioritize affordability and accessibility without compromising safety and efficacy [5]. Such approaches represent practical applications of justice, ensuring that biomedical engineering serves diverse populations rather than exclusively focusing on high-resource settings.

The consideration of environmental sustainability in biomedical engineering, as reflected in the "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" [10], represents an extension of justice concerns to intergenerational equity. Sustainable design practices, responsible end-of-life management for medical devices, and consideration of environmental impacts throughout the product lifecycle all reflect the expanding scope of ethical responsibility for biomedical engineers working within a principles framework.

Research Ethics and Integrity

The principles framework continues to guide the evolution of research ethics in biomedical engineering, particularly as new research methodologies emerge. The increasing use of human biospecimens and associated data raises complex questions about autonomy and informed consent, especially regarding future uses of samples and information [12]. Similarly, justice considerations inform debates about appropriate compensation for research participation and fair distribution of research benefits across communities.

Dual-use dilemmas, where biomedical research with therapeutic intent could potentially be misused for harmful purposes, present challenges that engage all four principles [5]. Addressing these concerns requires careful balancing of the potential benefits of research (beneficence) against potential harms from misuse (non-maleficence), while respecting researcher autonomy and ensuring equitable access to beneficial technologies (justice). These considerations have led to the development of specific oversight mechanisms for research with dual-use potential, representing an institutionalized application of the principles framework.

Table 3: Essential Ethical Assessment Tools for Biomedical Engineering Research

| Assessment Tool | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-Benefit Matrix | Systematic evaluation of potential harms and benefits | Research protocol development, device design | Prioritized risks, mitigation strategies |

| Informed Consent Checklist | Ensure comprehensive disclosure and understanding | Human subjects research, clinical trials | Documentation of consent process |

| Equity Impact Assessment | Evaluate distributional effects across populations | Technology implementation, study recruitment | Identification of potential disparities |

| Dual-Use Research Review | Assess potential for malicious application | Research with security concerns | Determination of oversight needs |

| Data Privacy Impact Assessment | Evaluate privacy risks in data handling | Studies involving personal health information | Data protection protocols |

The principle-based framework of beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy, and justice provides an indispensable foundation for ethical practice in biomedical engineering. These principles inform professional codes, institutional policies, research protocols, and design decisions, creating a comprehensive approach to addressing the complex ethical challenges inherent in developing technologies that directly impact human health and well-being. As biomedical engineering continues to evolve with advancements in AI, global health, and novel therapeutic approaches, these principles offer enduring guidance while requiring thoughtful application to new contexts and technologies.

The ongoing institutionalization of these principles through mechanisms such as the "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" represents significant progress in professional identity formation, creating explicit ethical commitments that parallel medicine's Hippocratic tradition. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this principles framework provides a shared language for identifying, analyzing, and resolving ethical dilemmas, ultimately supporting the development of biomedical innovations that responsibly serve human health needs while respecting fundamental moral values.

Biomedical engineering operates at the critical intersection of technology and human health, where professional decisions directly impact patient safety, public health, and societal well-being. This unique position necessitates a robust ethical framework to guide practitioners in their complex responsibilities. Ethical codes within biomedical engineering serve as foundational documents that enshrine the profession's commitment to public welfare, establishing clear expectations for safety, social responsibility, and professional conduct. These codes transform abstract moral principles into actionable standards, ensuring that technological innovation progresses in tandem with ethical considerations [5].

The development of ethical guidelines for biomedical engineering represents the profession's recognition of its profound responsibility toward patients, research participants, and society at large. Unlike many engineering disciplines, biomedical engineering directly addresses human health, making its ethical obligations particularly stringent. Professional societies including the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES), the Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS), and the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AdvaMed) have established comprehensive codes of ethics that outline the normative principles and obligations required to fulfill a biomedical engineer's commitment to honesty, conscientiousness in scientific inquiry, and advancement of public health [6] [5].

Core Ethical Principles in Biomedical Engineering

Fundamental Ethical Frameworks

Biomedical engineering ethics draws upon established bioethical principles while incorporating discipline-specific considerations relevant to technology development and implementation. The most prevalent ethical frameworks applied in biomedical engineering include:

Principle-Based Ethics: This approach utilizes the four fundamental principles of biomedical ethics: beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (avoiding harm), respect for autonomy (honoring patient self-determination), and justice (ensuring fairness and equity) [3]. These principles provide a systematic framework for analyzing ethical dilemmas in biomedical engineering practice and research.

Virtue Ethics: This framework focuses on cultivating moral character and virtues such as integrity, compassion, courage, and honesty among biomedical engineers, providing guidance for ethical decision-making in complex situations where rules may be insufficient [3].

Duty-Based Ethics (Deontology): Emphasizes adherence to moral rules and duties, helping biomedical engineers navigate situations where they must balance competing obligations and responsibilities, such as between patient confidentiality and public safety concerns [3].

Consequence-Based Ethics (Utilitarianism): Focuses on maximizing overall utility or well-being, which can be applied to biomedical engineering dilemmas to determine the course of action that produces the greatest good for the greatest number of people, particularly in resource allocation or public health policy contexts [3].

Specific Ethical Principles for Biomedical Engineering Practice

Beyond these established frameworks, biomedical engineering ethics incorporates specific principles directly relevant to professional practice:

Table 1: Core Ethical Principles in Biomedical Engineering

| Ethical Principle | Professional Application | Public Health Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Safety Primacy | Rigorous testing and validation of medical devices; risk-benefit analysis; quality control in manufacturing | Prevents patient harm; ensures device reliability; reduces adverse health events |

| Respect for Autonomy | Informed consent processes; clear communication of risks/benefits; patient education materials | Empowers patients in healthcare decisions; respects individual values and preferences |

| Justice and Equity | Designing accessible technologies; addressing healthcare disparities; fair resource allocation | Promotes equitable healthcare access; reduces health disparities among populations |

| Confidentiality | Data encryption; secure storage; strict access controls; HIPAA compliance | Protects patient privacy; prevents misuse of sensitive health information |

| Professional Competence | Continuing education; staying current with research; appropriate training and certification | Ensures high-quality care; reduces errors from outdated knowledge or skills |

| Honesty and Integrity | Accurate reporting of research findings; disclosure of conflicts of interest; transparency about limitations | Builds public trust; enables informed decision-making by clinicians and patients |

| Environmental Responsibility | Sustainable design practices; proper disposal of medical devices; reducing carbon footprint | Minimizes ecological harm; promotes long-term planetary health |

These principles collectively establish a comprehensive ethical foundation that guides biomedical engineers in fulfilling their primary obligation: to hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public in the performance of their professional duties [16] [3].

Codification of Ethics: From Principles to Practice

Professional Society Codes of Ethics

Professional societies have translated fundamental ethical principles into formal codes of conduct that establish normative standards for biomedical engineering practice. These codes provide specific guidance on ethical obligations and professional behavior:

Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) Code of Ethics: BMES establishes clear expectations for professional conduct, emphasizing that biomedical engineers must "hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public, including patients, research participants, coworkers, healthcare workers, and the public." The code explicitly prohibits harassment and discrimination while requiring reporting of ethical violations [17].

Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS) Code of Ethics: EMBS provides guidelines specifically addressing research ethics, including requirements to "respect human dignity and privacy of patients and human subjects," "ensure proper safeguarding of all confidential information," and "conduct clinical research studies in accordance with Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) and Good Clinical Practices (GCP)." The code also emphasizes environmental responsibility and interdisciplinary collaboration [6].

AdvaMed Code of Ethics: Focusing on medical technology companies, the AdvaMed Code provides guidance on ethical interactions with healthcare professionals, based on the values of "innovation, education, integrity, respect, responsibility, and transparency." The recently updated code specifically addresses data ethics in digital health technologies, emphasizing responsible data handling to protect patient privacy while delivering beneficial technologies [18].

The Biomedical Engineer's Pledge: A Symbolic Commitment

A significant development in biomedical engineering ethics is the creation of the "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge," which serves as a symbolic commitment for graduating students and professionals. Modeled after the Hippocratic Oath but adapted to the unique ethical landscape of biomedical engineering, the pledge comprises ten specific promises [10]:

- Holding paramount the safety, health, and well-being of patients, research participants, coworkers, healthcare workers, and the public

- Exercising the profession with integrity and responsibility

- Ensuring the autonomy and dignity of patients and research participants

- Safeguarding patient and research participant data

- Non-discrimination based on age, gender, race, religion, or other identity factors

- Avoiding patient deception or fraud

- Sharing knowledge without violating human rights

- Promoting replacement, reduction, and refinement of animal research

- Contributing to environmental and economic sustainability of healthcare

- Demonstrating respect and gratitude to teachers, colleagues, and society

The pledge explicitly introduces ethical aspects not fully addressed in some existing codes, including avoidance of patient deception, minimization of animal experimentation, and promotion of universal healthcare coverage [10].

Implementation Framework: Integrating Ethics into Practice

Ethical Integration in Research and Development

The translation of ethical principles into daily practice requires systematic approaches throughout the research, development, and implementation lifecycle of biomedical technologies. The following workflow illustrates how ethical considerations integrate into each stage of biomedical engineering practice:

This systematic integration of ethics throughout the technology development lifecycle ensures that biomedical innovations prioritize public health and social responsibility at every stage.

Educational Integration and Accreditation Standards

The integration of ethics into biomedical engineering education represents a critical implementation pathway for ensuring future professionals internalize these principles. ABET accreditation criteria specifically require that engineering programs demonstrate their graduates have "an ability to recognize ethical and professional responsibilities in engineering situations and make informed judgments, which must consider the impact of engineering solutions in global, economic, environmental, and societal contexts" [19].

Effective educational approaches for ethics integration include:

Dedicated Ethics Courses: Covering fundamental principles of justice, beneficence, nonmaleficence, objectivity, autonomy, integrity, loyalty, veracity, and accountability through case studies and guided debate [20] [10].

Project-Based Learning: Incorporating ethical analysis into design projects, requiring students to conduct risk-benefit assessments, examine environmental impacts, and address ethical, legal, and social aspects of their projects [20].

Safe Medical Device Design Training: Teaching risk classification, application of relevant standards, and risk minimization techniques through hands-on activities in project-based courses [20].

Sustainability Integration: Requiring life cycle analyses and environmental impact reporting alongside technical and business considerations in student projects [20].

The "Biomedical Engineer's Pledge" has been implemented as a graduation tradition at several universities, serving as a symbolic rite of passage that reinforces ethical commitment at the start of professional careers [10].

Essential Methodologies for Ethical Biomedical Engineering

Risk Assessment and Safety Protocol Implementation

Ensuring patient safety requires systematic methodologies for risk assessment and implementation of safety protocols throughout the device lifecycle:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Biomedical Engineering

| Research Component | Function in Ethical Practice | Implementation Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) Protocols | Protect human research participants; ensure ethical study design | Submit detailed research proposals; document informed consent processes; report adverse events |

| Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) Guidelines | Ensure quality and integrity of preclinical research data | Implement quality control systems; document all procedures; validate equipment and methods |

| Good Clinical Practice (GCP) Guidelines | Ensure ethical conduct of clinical trials; protect participant rights and data | Train research staff; establish monitoring procedures; maintain comprehensive documentation |

| Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) | Proactively identify potential device failures and harms | Systematic analysis of components and processes; risk priority number calculation; mitigation planning |

| Post-Market Surveillance Systems | Monitor device performance after commercialization; identify safety issues | Establish reporting mechanisms; track real-world performance; implement corrective actions when needed |

| Data Encryption and Security Protocols | Protect patient privacy and confidential health information | Implement access controls; secure data transmission; regular security audits |

These methodologies provide the practical framework for implementing ethical principles, particularly the foundational commitment to patient safety and well-being [6] [5] [3].

Ethical Dilemma Resolution Framework

Biomedical engineers frequently encounter ethical dilemmas requiring structured resolution approaches. The following framework provides a systematic methodology for addressing such situations:

This structured approach ensures that ethical decisions are made systematically rather than arbitrarily, incorporating relevant facts, principles, and stakeholder perspectives while aligning with established ethical codes [5] [3].

Case Studies in Ethical Success and Failure

Historical Case Analyses

Real-world cases provide powerful illustrations of the practical importance of ethical codes in biomedical engineering:

Therac-25 Radiation Therapy Machine (1980s): This case involved a software-controlled radiation therapy machine that malfunctioned, delivering lethal radiation doses to patients. The ethical failures included inadequate safety design, insufficient testing, lack of proper risk assessment, and failure to respond appropriately to early reports of problems. This case demonstrates the critical importance of rigorous safety protocols, comprehensive testing, and responsive reporting systems—all emphasized in modern ethical codes [5].

Bjork-Shiley Heart Valve (1970s-1980s): This prosthetic heart valve exhibited design flaws that led to strut fractures and patient deaths. Despite early indications of problems and reports of malfunctions, the valves remained on the market for years, resulting in hundreds of failures and fatalities. The case highlights the ethical imperative of responding promptly to safety concerns and prioritizing patient welfare over commercial interests [5].

Theranos (2010s): This company made misleading claims about its blood testing technology, committing widespread fraud that endangered patients who received inaccurate test results. The case illustrates violations of multiple ethical principles, including honesty, integrity, patient safety, and transparency [10].

Positive Implementation Cases

UBORA E-Infrastructure: This platform supports the cocreation of open-source medical devices, addressing ethical imperatives of technological equity and universal healthcare. By enabling collaborative development of safe, effective, and accessible medical technologies, this initiative embodies ethical principles of justice, equity, and global health responsibility [20].

Sustainable Medical Device Initiatives: Various projects have focused on developing environmentally sustainable medical technologies, addressing the ethical principle of environmental responsibility. These include devices designed for reduced resource consumption, improved recyclability, and lower carbon footprints throughout their lifecycle [20] [10].

As biomedical engineering continues to evolve with advancements in artificial intelligence, neurotechnology, synthetic biology, and personalized medicine, ethical codes must similarly progress to address emerging challenges. The ongoing revision of codes by professional societies such as AdvaMed, which recently updated its Code of Ethics to specifically address data-driven technologies, demonstrates this dynamic nature of ethical guidance in the field [18].

The fundamental commitment of biomedical engineering to public health, safety, and social responsibility remains constant, even as its technological capabilities transform. By establishing clear ethical principles, implementing them through systematic methodologies, and cultivating professional cultures that prioritize ethical practice, biomedical engineering can continue to develop innovative technologies that serve humanity while maintaining the public trust that forms the foundation of the profession.

The field of biomedical engineering operates at the critical intersection of technology, healthcare, and human welfare, making ethical practice not merely an adjunct but a foundational component of the profession. The principle of respect for persons forms a cornerstone of this ethical framework, encompassing the protection of patient autonomy, privacy, and the right to self-determination [6]. This principle manifests operationally through stringent adherence to protocols surrounding patient privacy, data confidentiality, and informed consent—each serving as a vital mechanism for upholding human dignity in healthcare and research settings [6]. As technology evolves to include more wearable devices, complex data analytics, and interconnected health systems, the responsibilities of biomedical engineers in implementing these safeguards have become both more complex and more critical.

The Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) and other professional organizations codify these obligations, emphasizing that professionals must "respect human dignity and privacy of patients and human subjects" and "ensure proper safeguarding of all confidential information" [6] [5]. These guidelines are not abstract ideals but practical requirements that directly impact patient safety, trust in medical institutions, and the integrity of scientific research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, navigating this landscape requires a sophisticated understanding of both technical requirements and ethical imperatives, as failures can result in profound harm to individuals and populations, particularly vulnerable groups [21]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for integrating these essential principles into daily practice and research methodologies.

Patient Privacy and Data Confidentiality

Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) establishes the primary federal standard for protecting patient health information in the United States [22]. HIPAA consists of two main rules: the Privacy Rule, which governs the use and disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI), and the Security Rule, which sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronic PHI (ePHI) [22]. PHI encompasses any individually identifiable health information transmitted or maintained in any form or medium, including electronic, paper, or oral communication [22]. The scope of these regulations extends beyond traditional healthcare settings to include biomedical engineers involved in device design, data system development, and clinical research.

HIPAA's definition of PHI includes 18 specific identifiers that constitute protected information, ranging from names and geographic subdivisions to device identifiers and serial numbers [22] [21]. The law applies to covered entities (healthcare providers, health plans, healthcare clearinghouses) and their business associates, which includes many biomedical engineering contexts where patient data is accessed, processed, or stored [22]. Importantly, many states have implemented more stringent privacy laws, particularly regarding sensitive health information related to HIV status, mental health, genetic testing, and substance abuse treatment—in such cases, the more restrictive rule takes precedence [22].

Table 1: Key Elements of Protected Health Information (PHI) Under HIPAA

| Category | Specific Identifiers | Protection Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Identifiers | Names, geographic subdivisions smaller than a state, all elements of dates (except year) directly related to an individual, telephone numbers, vehicle identifiers | Must be removed for de-identified data sets; requires strict access controls in identified form |

| Digital Identifiers | Email addresses, IP addresses, URLs, device identifiers and serial numbers | Must be encrypted during transmission and storage; secure authentication required for access |

| Biometric Identifiers | Fingerprints, voiceprints, full face photographic images | Considered highly sensitive; requires enhanced protection and specific authorization for use |

| Administrative Identifiers | Medical record numbers, health plan beneficiary numbers, account numbers, certificate/license numbers | Must be protected in all forms; requires audit trails for access and disclosure |

Practical Implementation in Biomedical Engineering

Biomedical engineers implement data privacy through both technical safeguards and organizational policies. Technical safeguards include encryption of data both in transit and at rest, implementation of secure authentication protocols, and regular security audits [5]. Particularly vulnerable areas include wireless networks used to access medical records, which must have encryption functions activated to prevent interception, and portable storage devices like laptops and flash drives, which should either avoid storing PHI entirely or employ robust encryption methods when storage is necessary [22].

Organizational policies must address access controls, workforce training, and breach notification procedures. The HIPAA security rule emphasizes risk analysis, requiring healthcare institutions and their partners to "identify and address the appropriate security options to ensure data security" [22]. This includes developing protection against reasonably anticipated threats to data integrity and confidentiality, ensuring compliance among workforce members, and implementing unique user identification systems that go beyond basic password protection [22]. Biomedical engineers developing medical devices or health information systems must incorporate privacy-by-design principles, building in security features during the development phase rather than adding them as an afterthought.

The emergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning in healthcare introduces novel privacy challenges, as these systems often require large datasets for training and validation [21]. Biomedical engineers must ensure that data used for algorithm development does not compromise patient privacy through re-identification risks, even in supposedly de-identified datasets. This requires sophisticated techniques such as differential privacy and federated learning, which allow model development without centralizing sensitive patient data [21].

Figure 1: The Protected Health Information (PHI) Lifecycle. All phases require specific security measures with destruction occurring only after meeting legal retention requirements [21].

Informed Consent in Research and Clinical Applications

Theoretical Foundations and Ethical Imperatives

Informed consent represents a fundamental ethical and legal requirement in both clinical practice and research contexts, serving as the practical embodiment of respect for personal autonomy [23]. Historically rooted in responses to ethical abuses such as the Tuskegee Study and Nazi medical experiments, informed consent has evolved from a simple signature on a document to a comprehensive communication process between healthcare providers/researchers and patients/subjects [23]. This process ensures that individuals maintain the ultimate authority over what happens to their bodies and personal health information, particularly in research environments where biomedical engineers may be developing novel devices or therapeutic approaches.

The functional purpose of informed consent extends beyond mere legal protection for institutions and researchers; it represents the intersection of values including autonomy, non-domination, self-ownership, and personal integrity [23]. For consent to be truly "informed," it must encompass several key elements: the nature of the procedure or research intervention, the potential risks and benefits, reasonable alternatives, and the risks and benefits of those alternatives [23]. Additionally, researchers must assess the patient's or subject's understanding of these elements, ensuring comprehension rather than merely providing information. This is particularly crucial in biomedical engineering contexts where complex technologies may be difficult for laypersons to understand.

Methodological Implementation and Documentation

The implementation of valid informed consent requires structured methodologies that address common barriers to understanding. The Joint Commission requires documentation of all consent elements, which typically includes: the nature of the procedure or intervention, risks and benefits, reasonable alternatives, risks and benefits of alternatives, and assessment of patient understanding [23]. Biomedical engineers involved in clinical trials or device testing must ensure that consent processes adequately convey technical information in accessible language, using appropriate educational materials and verification techniques.

Effective methodologies for obtaining informed consent include:

- The Teach-Back Method: Asking patients to explain in their own words what they have understood about the procedure, risks, and alternatives, which allows for correction of misunderstandings [23].

- Utilization of Graphical Tools and Interactive Media: Visual representations of complex procedures or statistical risks can significantly improve comprehension compared to purely verbal or written descriptions [23].

- Cultural and Linguistic Adaptation: Working with medical interpreters for non-native speakers and adapting materials to account for cultural health beliefs and decision-making patterns [23].

- Structured Decision-Making Tools: Using evidence-based templates that standardize the presentation of risk/benefit information while allowing personalization to individual clinical circumstances.

Table 2: Standards for Adequate Informed Consent in Research Settings

| Legal Standard | Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective Standard | What this specific patient needs to know and understand to make an informed decision | Ideal for personalized medicine approaches; requires individualized assessment of patient values and comprehension |

| Reasonable Patient Standard | What the average patient would need to know to be an informed participant in the decision | Most common standard in clinical practice; balances efficiency with respect for autonomy |

| Reasonable Clinician Standard | What a typical clinician would disclose about a procedure or intervention | Traditional approach that defers to professional norms; increasingly supplemented by patient-centered standards |

Documentation of informed consent must extend beyond a signed form to include notes in progress records or research files that reflect the discussion process, specific questions asked by the patient or subject, and the responses provided [23]. This documentation becomes particularly important in biomedical engineering research where innovative devices or therapies may have uncertain risk profiles or novel mechanisms of action. Research indicates that the four required elements of informed consent—nature of the procedure, risks, benefits, and alternatives—are documented on consent forms only 26.4% of the time, highlighting a significant area for improvement in both clinical and research settings [23].

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Protocol for Ethical Implementation of Human Subject Research

Biomedical engineering research involving human subjects requires rigorous protocols to ensure ethical conduct. The following methodology outlines key steps for maintaining patient privacy, confidentiality, and valid informed consent:

Pre-Study Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval: Submit detailed research protocol to the IRB or independent ethics committee, including data collection methods, informed consent documentation, privacy safeguards, and procedures for vulnerable populations [5]. The IRB functions include approving research, providing ethical oversight, conducting periodic reviews, requiring modifications to procedures, and ensuring compliance with state and federal guidelines [5].

Participant Recruitment and Screening: Implement targeted recruitment strategies that avoid coercion or undue influence. Screen potential participants for factors that may affect their ability to provide informed consent, such as language barriers, cognitive impairments, or emotional distress [23]. For participants with limited English proficiency, utilize qualified medical interpreters rather than family members.

Comprehensive Informed Consent Process: Conduct the consent discussion in a private setting with adequate time for questions and reflection [23]. Present information using clear, non-technical language appropriate to the participant's health literacy level. Utilize the teach-back method to verify comprehension: "To make sure I've explained everything clearly, could you please tell me in your own words what you understand about this study?" [23].

Data Collection and Management: Implement data encryption for all electronic protected health information (ePHI) during transmission and storage [22]. Utilize secure data capture platforms such as Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which complies with HIPAA standards and supports single- and multiple-site research studies while allowing data to be stored at local institutions [21]. De-identify data whenever possible during export and analysis.

Ongoing Monitoring and Adverse Event Reporting: Establish clear protocols for monitoring participant safety throughout the study period. Report adverse events to the IRB according to established timelines. For long-term studies, implement periodic re-consent processes if new risks emerge or procedures change significantly.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Ethical Biomedical Engineering Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Ethical Application |

|---|---|---|

| REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) | Secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases | Enables HIPAA-compliant data collection; supports single- and multi-site research while maintaining institutional control of data [21] |

| HIPAA-Limited Data Sets | Data sets with certain direct identifiers removed but containing potentially identifiable information | Allows sharing of data for research without individual authorization under specific circumstances; requires data use agreements [21] |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) | Independent ethics committee that reviews research involving human subjects | Provides ethical oversight and approval; ensures participant rights and welfare are protected throughout research process [5] |

| Health Literacy Assessment Tools | Validated instruments to assess participant understanding of research information | Identifies comprehension gaps; allows researchers to tailor consent discussions to individual needs [23] |

| Data Encryption Software | Programs that encode data to prevent unauthorized access | Protects confidentiality during data transmission and storage; essential for mobile devices and portable storage media [22] |

Figure 2: Informed Consent Protocol Workflow. The process emphasizes comprehension verification through methods like teach-back before proceeding to research implementation [23].

Case Studies and Ethical Analysis

Historical Failures and Their Impact on Current Standards

Analysis of historical cases provides valuable lessons for contemporary biomedical engineering practice. The Therac-25 radiation therapy machine incidents represent a pivotal case where lapses in safety design and risk assessment led to patient fatalities [5]. This case demonstrates how engineering decisions directly impact patient safety and why rigorous testing, transparency in reporting potential risks, and ongoing monitoring are ethical imperatives, not just technical considerations. The failures included insufficient safety redundancies, poor error reporting systems, and inadequate investigation of early incident reports—all of which contributed to catastrophic outcomes.

The Bjork-Shiley heart valve case further illustrates the consequences of prioritizing commercial interests over patient safety [5]. Despite early indications of anomalies and reports of malfunctions, the valves remained on the market for years, resulting in over 600 valve failures and fatal outcomes. This case highlights the ethical responsibility of biomedical engineers to advocate for patient safety even when facing commercial or institutional pressure, and to ensure transparent reporting of potential device risks throughout the product lifecycle.

Contemporary Challenges in Data Privacy

Modern biomedical engineering faces novel ethical challenges regarding patient data ownership and privacy. The increasing interest of for-profit companies in acquiring databases from large healthcare systems creates new vulnerabilities for patient privacy [21]. Such arrangements raise ethical concerns about sharing patient data with entities that may exploit it for commercial interests or target vulnerable populations. Of particular concern is the use of data voluntarily provided by patients for research purposes being redirected toward commercial applications without explicit consent for these secondary uses [21].

Biomedical engineers developing health information systems, wearable devices, or data analytics platforms must implement privacy-by-design principles that anticipate these potential misuses. This includes building in data governance structures that give patients control over how their information is used, implementing robust de-identification techniques that withstand re-identification attempts, and establishing transparent policies regarding data sharing with third parties [21]. The ethical obligation extends beyond legal compliance to ensuring that data systems respect the spirit of patient trust and the context in which data was originally provided.

The principles of patient privacy, data confidentiality, and informed consent represent more than regulatory requirements—they form the ethical bedrock of trustworthy biomedical engineering practice. As technology continues to evolve with artificial intelligence, wearable sensors, and complex data analytics, these principles must remain central to both research and clinical applications. Biomedical engineers have a professional responsibility to implement systems that not only advance healthcare but also protect the fundamental rights and dignity of patients and research subjects.

Future challenges will include developing ethical frameworks for emerging technologies such as organ bioengineering, complex tissue creation, and neural interfaces, all of which present novel questions about patient safety, privacy, and consent [5]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion in research requires biomedical engineers to develop consent processes and data protection measures that are culturally competent and accessible to diverse populations [23] [5]. By maintaining a commitment to the principle of respect for persons through robust privacy protections and meaningful informed consent processes, the biomedical engineering community can continue to advance human health while upholding its fundamental ethical obligations.

Research integrity forms the ethical foundation of scientific advancement, particularly in biomedical engineering where research directly impacts healthcare and human well-being. Upholding the highest standards of rigor, honesty, and transparency is not merely aspirational but essential for maintaining public trust and ensuring the reliability of scientific evidence. As articulated by leading scientific organizations, research integrity encompasses core elements of honesty, rigour, transparency, open communication, care and respect, and accountability [24]. Within the context of biomedical engineering, this ethical framework governs both the reporting of scientific findings and the humane conduct of animal experimentation, ensuring that research advances knowledge while maintaining ethical responsibilities toward all subjects involved in the research process.

Professional societies like the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES) and IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS) establish codes of ethics that provide essential guidelines for ethical conduct. These codes emphasize respect for human dignity, privacy, proper safeguarding of confidential information, and responsible reporting of research results [6]. Furthermore, they stress the importance of observing the rights of human research subjects and ensuring responsible and humane use of animals in research [6]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to implementing these ethical principles through robust scientific reporting standards and humane animal experimentation protocols, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the biomedical field.

Fundamental Principles of Research Integrity

Research integrity encompasses a comprehensive framework of principles and responsibilities that guide ethical scientific practice. The Concordat to Support Research Integrity, endorsed by major research institutions, outlines five fundamental principles that all researchers should uphold: (1) maintaining the highest standards of rigour and integrity in all research aspects; (2) ensuring research is conducted according to appropriate ethical, legal and professional frameworks; (3) supporting a research environment underpinned by a culture of integrity; (4) using transparent, timely, and fair processes for addressing misconduct allegations; and (5) working collaboratively to strengthen research integrity [24].