Neural Engineering 2025: Decoding Brain-Computer Interfaces, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on how neural engineering interfaces with the nervous system.

Neural Engineering 2025: Decoding Brain-Computer Interfaces, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on how neural engineering interfaces with the nervous system. It explores the foundational neuroscience of survival circuits, details the latest methodological advances in implanted and non-invasive brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), addresses critical troubleshooting in translation and ethics, and examines validation strategies through synthetic tissue models and regulatory pathways. The content synthesizes cutting-edge research from 2025, highlighting both immediate clinical applications and the long-term trajectory of neurotechnology in biomedicine.

The Primal Brain: Uncovering Foundational Neural Circuits of Survival and Homeostasis

The human brain's most fundamental role, maintaining internal stability amidst fluctuating external environments, represents a core organizing principle of nervous system function. This maintenance of homeostasis—the stable physiological condition essential for survival—encompasses the regulation of blood pressure, glucose levels, energy expenditure, inflammation, and breathing rate [1]. These processes are governed by specialized networks of neurons working continuously in the background to preserve internal stability against environmental challenges. This homeostatic function predates and underlies more recently evolved cognitive capabilities, establishing it as the brain's oldest and most essential job [1].

Within the context of neural engineering, understanding these fundamental homeostatic circuits provides the foundational knowledge required to develop effective interfaces and interventions. As the field advances toward creating direct links between the nervous system and external devices for treating sensory, motor, or other neural disabilities, comprehending these basic survival mechanisms becomes paramount [2]. Neural engineering combines principles from neuroscience, engineering, computer science, and mathematics to study, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems, with applications ranging from brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) to neuroprosthetics and neuromodulation therapies [3]. This interdisciplinary approach relies fundamentally on deciphering how the brain maintains stability, offering insights for developing technologies that can interface with or restore these essential functions when compromised by injury, disease, or aging.

Computational Frameworks: Modeling Homeostatic Preservation

Biophysically Grounded Modeling of Age-Related Compensation

Advanced computational approaches have revealed remarkable homeostatic mechanisms that preserve brain function despite structural decline. Research demonstrates that the aging brain maintains functional coordination among neural assemblies through specific neurocomputational principles despite structural deterioration [4]. Using multiscale, biophysically grounded modeling constrained by empirically derived anatomical connectomes, researchers have identified how neurotransmitters compensate for structural loss during lifespan aging.

These models incorporate key biological constraints to simulate large-scale brain dynamics:

- Local inhibitory and excitatory neuronal populations with uniform properties across brain regions

- Algorithmic adjustment of GABA and glutamate concentrations to maintain regional homeostasis

- Preservation of metastability as the brain's optimal dynamic working point

- Maintenance of critical firing rates at approximately 3Hz across all brain regions, consistent with experimental data [4]

Table 1: Key Parameters in Multiscale Dynamical Mean Field (MDMF) Models of Brain Homeostasis

| Parameter | Function in Homeostasis | Age-Related Change | Impact on Network Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA Concentration | Regulates inhibitory balance | Remains invariant | Preserves topological properties of functional connectivity |

| Glutamate Concentration | Regulates excitatory signaling | Reduced with aging | Compensates for structural connectivity loss |

| Metastability | Measures brain's readiness to respond to stimuli | Maintained at optimal level | Ensures functional integration despite structural decline |

| Global Coupling Strength | Determines interaction strength between regions | Algorithmically tuned | Compensates for white-matter degradation |

Quantitative Validation Through Graph Theory

The homeostatic preservation of brain function can be quantified using graph-theoretic metrics applied to functional connectivity networks. Studies analyzing three distinct independent datasets have validated that the invariant GABA and reduced glutamate mechanism successfully explains topological variations in functional connectivity along the lifespan [4]. These computational findings demonstrate how the brain engages in continuous functional reorganization primarily driven by excitatory neurotransmitters to compensate for structural insults associated with aging.

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Homeostatic Circuits

Neural Circuit Dissection Approaches

Cutting-edge experimental research has identified specific neural circuits responsible for maintaining core homeostatic functions. The following experimental protocols represent methodologies for investigating these survival circuits:

Protocol 1: Identifying Thermoregulatory Feeding Circuits

- Objective: Identify neural circuits linking cold exposure to feeding behavior

- Methodology:

- Expose animal models to prolonged cold conditions

- Use calcium imaging or electrophysiology to track neuronal activation in thalamic Xiphoid nucleus

- Employ optogenetic or chemogenetic manipulation to validate circuit function

- Measure metabolic changes and feeding behavior during circuit manipulation

- Validation: Demonstrated that the Xiphoid nucleus circuit regulates cold-induced increases in metabolism and subsequent food-seeking behavior [1]

Protocol 2: Dissecting Satiety Signaling Pathways

- Objective: Map neural populations governing feeding cessation

- Methodology:

- Utilize in vivo recording during feeding behavior

- Identify distinct neuronal populations in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract

- Characterize separate populations receiving: (a) ingestion and taste signals from the mouth, and (b) gut fullness signals

- Test causal roles through selective inhibition/activation

- Outcome: Revealed parallel pathways for immediate meal termination (oral signals) and long-term satiety learning (gut signals) [1]

Protocol 3: Analyzing Body Temperature Regulation Circuits

- Objective: Identify neural mechanisms controlling torpor and fever responses

- Methodology:

- Record from median preoptic nucleus neurons during temperature challenges

- Manipulate neuronal activity during induced torpor and sickness responses

- Measure body temperature changes and metabolic markers

- Map connectivity to downstream effector systems

- Finding: The same neuronal population in the median preoptic nucleus acts as a bidirectional switch for body temperature, reducing temperature during torpor and permitting fever during sickness [1]

Molecular and Genetic Approaches

Protocol 4: Mapping Stress Response Pathways in Peripheral Tissues

- Objective: Identify neural mechanisms linking stress to tissue changes

- Methodology:

- Analyze sympathetic nervous system innervation of hair follicles and skin

- Measure noradrenaline release during stress conditions

- Track stem cell populations (melanocyte stem cells, hair follicle cells)

- Identify autoimmune responses triggered by neural activation

- Application: Revealed mechanisms through which stress induces hair graying and loss through sympathetic nerve-mediated stem cell depletion [1]

Protocol 5: Circuit Mapping of Protective Reflexes

- Objective: Identify sensory neurons mediating coughing and sneezing

- Methodology:

- Use single-cell RNA sequencing to characterize neuronal populations in nasal and tracheal passages

- Employ genetic targeting to label specific sensory neuron subtypes

- Test necessity and sufficiency through selective ablation and activation

- Measure reflex responses to irritants and pathogens

- Outcome: Identified distinct neuronal populations in nasal passages (sneezing) and trachea (coughing) that mediate protective upper airway reflexes [1]

Neural Engineering Interfaces with Homeostatic Circuits

Technologies for Interfacing with Stability Mechanisms

Neural engineering develops interfaces to monitor and modulate the homeostatic circuits maintaining internal stability. These technologies represent the applied extension of basic research into the brain's fundamental survival mechanisms:

Table 2: Neural Engineering Technologies for Homeostatic Regulation

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Homeostatic Applications | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Electrical modulation of neural circuits | Parkinson's disease, OCD, depression, chronic pain | FDA-approved for multiple conditions [3] |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | Non-invasive magnetic field stimulation | Treatment-resistant depression, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, migraine | FDA-approved for depression and OCD [3] |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Electrical stimulation of vagus nerve | Epilepsy, treatment-resistant depression, inflammatory conditions | FDA-approved for epilepsy and depression [3] |

| Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) | Direct brain-external device communication | Paralysis, motor restoration, communication | Early-stage clinical trials [2] |

| Neuroprosthetics | Replacement of damaged neural function | Cochlear implants, retinal implants, motor prostheses | Clinically established to emerging [2] |

Quantitative Benchmarks for Neural Interface Validation

The development of effective neural interfaces requires rigorous validation methods. Recent research has established quantitative benchmarks for evaluating neural network approaches to feature selection in complex biological data:

- Synthetic Dataset Validation: Created specialized datasets (RING, XOR, RING+OR, RING+XOR+SUM, DAG) with known ground truth to test detection of non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data [5]

- Performance Benchmarking: Systematic assessment of Deep Learning-based feature selection methods against traditional approaches like Random Forests, TreeShap, mRMR, and LassoNet [5]

- Reliability Assessment: Evaluation of gradient-based feature attribution techniques (Saliency Maps, Integrated Gradients, DeepLift) for interpreting neural network decisions [5]

These benchmarking approaches ensure that neural engineering technologies can reliably interpret complex neural signals related to homeostatic function, which is particularly important for developing closed-loop systems that automatically adjust stimulation parameters based on physiological feedback.

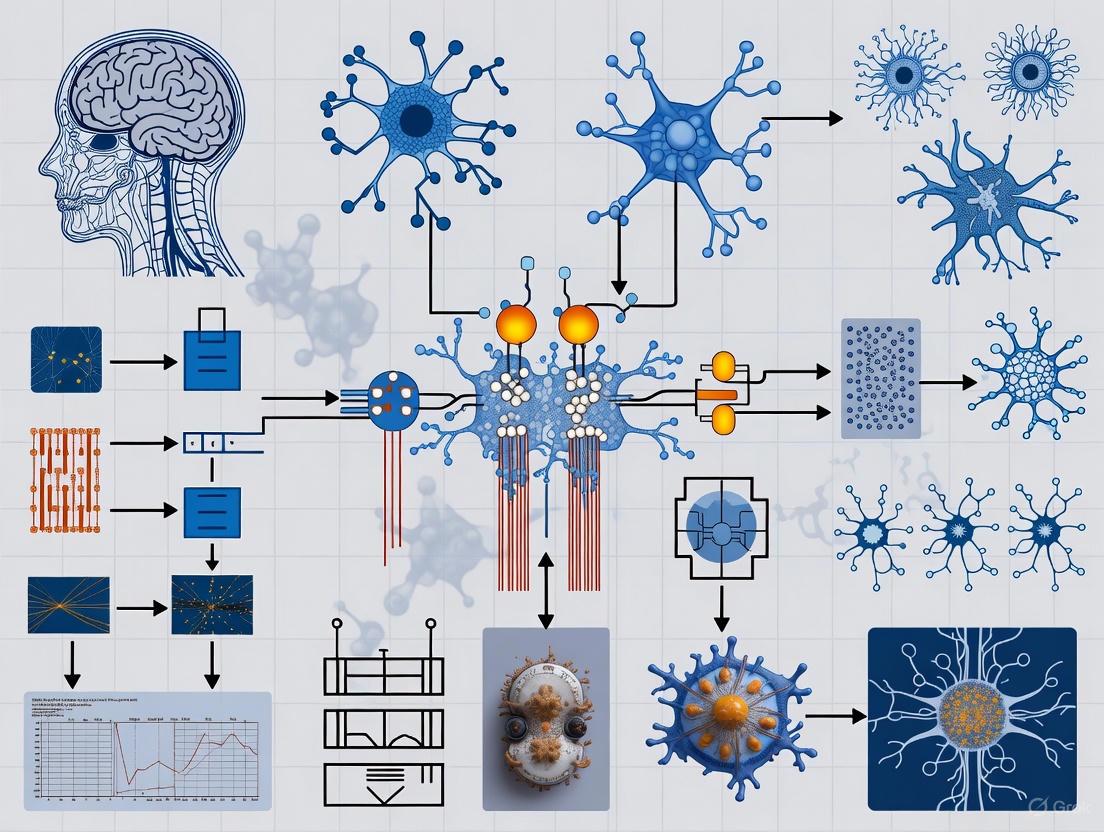

Visualization of Homeostatic Neural Circuits

Core Homeostatic Circuit Architecture

Homeostatic Neural Circuit Architecture

Neurotransmitter Homeostasis in Aging

Neurotransmitter Homeostasis in Aging

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating Neural Homeostasis

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Use in Homeostasis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multielectrode Arrays | Record extracellular action potentials from neuronal populations | Mapping neural ensemble activity in feeding circuits [2] |

| Optogenetics Tools | Light-sensitive opsins for precise neuronal control | Causally testing thermoregulation circuits [1] |

| Chemogenetics (DREADDs) | Designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs | Modulating specific neural pathways in satiety circuits [1] |

| Calcium Indicators (GCaMP) | Fluorescent sensors of neuronal activity | Monitoring population dynamics in homeostasis centers [1] |

| Anatomical Tracers | Neural pathway mapping (anterograde/retrograde) | Defining connectivity of homeostatic circuits [4] |

| Bioplistic Gene Delivery | Ballistic delivery of genetic material | Introducing receptors or sensors into specific nuclei [2] |

| fMRI/MRI | Macroscopic brain imaging and connectomics | Mapping large-scale network changes in aging [4] |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Simulate neural dynamics and connectivity | Testing homeostasis principles in silico [4] |

The brain's maintenance of internal stability through specialized neural circuits represents not only its most ancient function but also a crucial target for neural engineering interventions. Research has revealed that homeostatic preservation operates across multiple scales, from neurotransmitter-level compensation in aging to dedicated circuits regulating feeding, thermoregulation, and protective reflexes. The computational principle of maintaining metastability—a state of perpetual transition between order and disorder—emerges as a fundamental mechanism preserving brain function despite structural decline [4].

Neural engineering interfaces with this fundamental biology by developing technologies that can monitor, interpret, and modulate these homeostatic circuits. From deep brain stimulation for neurological disorders to brain-computer interfaces for paralysis, these applications build upon our understanding of how the brain naturally maintains stability. As quantitative benchmarking approaches improve the reliability of neural signal interpretation [5], and as experimental methods advance our dissection of homeostatic circuits [1], the potential for targeted interventions grows accordingly. This synergy between basic neuroscience and neural engineering promises not only to restore lost function in disease states but also to enhance our fundamental understanding of the brain's oldest and most essential job: maintaining the internal stability that enables all other functions.

The nervous system performs the brain's oldest job: maintaining internal stability amidst fluctuating external environments [1]. Neural circuits for energy balance are fundamental evolutionary adaptations that enable organisms to regulate blood pressure, glucose levels, energy expenditure, inflammation, and breathing through sophisticated networks working quietly in the background [1]. Understanding these circuits represents a critical frontier in neuroscience with profound implications for treating metabolic disorders, developing therapeutic hypothermia, and advancing neural engineering applications.

This technical guide examines the architectural principles and functional mechanisms of neural circuits governing energy homeostasis, focusing specifically on the transition from hunger states to torpor—a regulated hypometabolic state enabling survival during fasting. The integration of neural engineering methodologies with basic neuroscience research is revolutionizing our capacity to map, manipulate, and model these circuits, offering unprecedented opportunities for therapeutic intervention and bidirectional neural interfaces.

Core Neural Circuits Regulating Energy Balance

Central Circuitry for Feeding Behavior and Satiety

The neural regulation of feeding involves distributed circuits that integrate sensory signals, metabolic needs, and environmental cues. Research presented at the MIT "Circuits of Survival and Homeostasis" symposium highlights several key components:

Xiphoid Nucleus Circuitry: Li Ye's lab at Scripps Research identified a circuit centered in the Xiphoid nucleus of the thalamus that regulates behavior in response to prolonged cold exposure and energy consumption [1]. This circuit mediates the increased feeding behavior necessary to maintain energy balance during cold stress.

Brainstem Satiety Circuits: Zachary Knight's research at UCSF reveals dual mechanisms for meal termination in the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) [1]. One population of NTS neurons receives signals about ingestion and taste from the mouth to provide immediate "stop eating" signals, while a separate neural population receives fullness signals from the gut and teaches the brain over time how much food leads to satisfaction. These complementary systems collaboratively regulate feeding pace and volume.

Metabolic State Switching: Clifford Saper's research demonstrates that neurons in the median preoptic nucleus dictate metabolic states, serving as a two-way switch for body temperature [1]. These same neurons regulate both torpor during fasting and fever during sickness, highlighting their fundamental role in adaptive thermoregulation.

Table 1: Key Neural Circuits in Energy Balance

| Circuit Location | Primary Function | Regulatory Role | Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xiphoid nucleus (Thalamus) | Cold-induced feeding | Links thermal stress to energy intake | Mouse cold exposure models |

| Caudal NTS (Brainstem) | Meal termination | Processes orosensory and gastric signals | Real-time feeding behavior analysis |

| Median Preoptic Nucleus (Hypothalamus) | Metabolic state switching | Controls torpor/fever transitions | Chemogenetic manipulation in mice |

| VLM-CA neurons (Brainstem) | Torpor induction | Coordinates cardiovascular and thermoregulatory changes | Fasting-induced torpor model in mice |

| VTA-NAc-mPFC pathway | Reward valuation | Integrates motivational and metabolic signals | MDD computational models in mice |

Torpor Regulation Circuits

Torpor represents an energy-conserving state characterized by pronounced reductions in body temperature, heart rate, and thermogenesis. Recent research illuminates the specialized circuits governing this adaptive hypometabolism:

Brainstem Catecholaminergic Initiation: Catecholaminergic neurons in the ventrolateral medulla (VLM-CA) play a pivotal role in initiating torpor during fasting [6]. These neurons become activated approximately 6 hours post-food deprivation, preceding the onset of core body temperature decline. Inhibition of VLM-CA neurons significantly disrupts fasting-induced torpor, reducing core temperature drops, physical activity suppression, and torpor duration [6].

Coordinated Physiological Control: VLM-CA neurons orchestrate multiple torpor-related physiological changes through distinct projection pathways [6]. They regulate heart rate via projections to the dorsal motor vagal nucleus and control thermogenesis through connections with the medial preoptic area. This distributed control mechanism enables the coordinated reduction of cardiovascular function and energy expenditure characteristic of torpor.

Temporal Dynamics: Activation of VLM-CA neurons produces a distinctive physiological sequence where heart rate reduction precedes body temperature decline, mirroring patterns observed in natural torpid animals [6]. This temporal relationship suggests a likely causal relationship between cardiovascular changes and subsequent thermoregulatory adjustments.

Energy-State-Dependent Temporal Organization

The brain's regulation of energy balance extends to the temporal organization of behavior, as demonstrated by research on nocturnal-diurnal switching:

Energy Balance and Behavioral Timing: Research by van Rosmalen et al. demonstrates that energy balance can fundamentally reorganize daily activity patterns [7]. By manipulating the wheel-running activity required for food rewards (work-for-food paradigm), researchers can switch mice from nocturnal to diurnal phenotypes, simulating natural responses to food scarcity.

Transcriptomic Reprogramming: The transition between nocturnal and diurnal states involves extensive transcriptomic changes across multiple brain regions [7]. The habenula emerges as particularly affected, suggesting a crucial role in behavioral timing switches, while the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) shows more limited changes in core clock gene expression.

Metabolic Drivers: The nocturnal-diurnal switch follows the circadian thermoenergetics hypothesis, where animals shift activity to warmer daytime periods to reduce energy expenditure when facing energetic challenges [7]. This behavioral adaptation is accompanied by approximately 40% lower plasma glucose levels throughout the 24-hour cycle.

Experimental Methodologies and Neural Engineering Approaches

Advanced Circuit Mapping and Manipulation

Contemporary neural engineering provides powerful tools for delineating energy balance circuits:

Chemogenetic Circuit Interrogation: Studies of VLM-CA neurons employ designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) to precisely manipulate neuronal activity [6]. For inhibition, researchers bilaterally inject AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry into the VLM of Dbh-Cre mice, enabling neuronal silencing through CNO administration. For activation, AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry enables chemogenetic excitation. Electrophysiological validation confirms appropriate neuronal responses to CNO administration.

Functional Circuit Tracing: VLM-CA neuron projections are mapped using anterograde and retrograde tracing techniques, revealing functional connectivity to the dorsal motor vagal nucleus (cardiac control) and medial preoptic area (thermoregulation) [6]. This projection mapping establishes the architectural basis for coordinated physiological control during torpor.

Temporal Activity Mapping: Fos immunostaining at multiple time points (6, 9, and 15 hours post-food deprivation) reveals the dynamic recruitment of VLM-CA neurons during fasting-induced torpor [6]. Over 95% of fasting-activated Fos+ VLM-CA neurons localize to the rostral and middle VLM regions, with peak activation at 6 hours preceding torpor initiation.

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Neural Circuit Analysis

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Parameters | Output Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemogenetic Manipulation (DREADDs) | Causally link neuronal activity to physiological outcomes | AAV delivery; CNO dosage: 1-5 mg/kg; Cre-dependent expression | Body temperature (telemetry), heart rate, activity monitoring, metabolic rate (O2 consumption/CO2 production) |

| Fos Immunostaining | Map neuronal activation patterns | Tissue collection at strategic time points; Fos antibody staining | Percentage of Fos+ neurons in target populations; spatial distribution of activation |

| Work-for-Food Paradigm | Investigate energy-state-dependent behavior | Progressive increase in wheel revolutions per food pellet (e.g., +20 revs/pellet for 3 days, then +10 revs/pellet) | Activity onset/offset timing, phase advances, body weight, food obtained, plasma glucose levels |

| Rhythmic Transcriptome Analysis | Identify molecular adaptations | Tissue collection every 4h over 24h; RNA-seq of 17 brain regions | Cycling transcripts identification; phase and amplitude comparisons between states |

Computational Modeling and Neural Interface Technologies

Computational approaches and advanced neural interfaces provide complementary insights into energy balance circuits:

Computational Modeling of Energy Coding: Research by Li et al. develops biological neural network models of the VTA-NAc-mPFC dopaminergic pathway to investigate neural energy coding patterns in major depressive disorder [8]. These models calculate neural energy consumption based on ion channel dynamics and reveal disease-specific alterations in energy efficiency.

Visual Analysis Tools: Novel interactive visualization systems assist researchers in extracting hypothetical neural circuits constrained by anatomical and functional data [9]. These tools enable Boolean query-based neuron identification, linked pathway browsing, and multi-scale visualization from individual neurons to brain regions.

Quantum Neural Networks: Emerging computational approaches employ quantum and hybrid quantum neural networks to solve complex differential equations governing neural dynamics [10]. Under favorable parameter initializations, these networks can achieve higher accuracy than classical neural networks with fewer parameters and faster convergence.

Neural Engineering Interfaces with Nervous System Research

Bidirectional Neural Interfaces

Neural engineering interfaces are transforming our approach to energy balance circuitry through bidirectional communication with the nervous system:

Implanted Brain-Computer Interfaces: Advanced implanted BCIs provide unprecedented access to neural signals governing energy-related behaviors [11]. Research focuses on optimizing device design, neural encoding strategies, and understanding device-user co-adaptation for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Artificial Sensory Feedback: Electrical stimulation of central and peripheral nervous system structures creates artificial sensations that can be integrated into energy balance circuits [11]. Animal studies investigate how stimulation-based feedback influences neural circuits, induces neuroplasticity, and modulates behavior in neuroprosthetic applications.

Human-Centered Design: The neural engineering field increasingly emphasizes centering disabled users in technology development, incorporating principles of disability justice and design justice to create effective, ethically grounded solutions [11].

Translation and Commercialization Pathways

Efforts to translate basic research on energy balance circuits into clinical applications face distinct challenges and opportunities:

Neurotechnology Incubators: Initiatives like NeuroTech Harbor and the NIH Blueprint Medtech Incubator hubs provide resources to accelerate neurotechnology translation, addressing risks to commercial viability, technical development, and team composition [11].

Regulatory Navigation: Successful translation requires understanding FDA regulatory pathways for neurological devices, including requirements for demonstration of safety and efficacy through appropriate clinical trial designs [11].

Investment Landscape: Neurotechnology ventures addressing energy balance disorders must navigate a complex investment landscape, requiring compelling value propositions, clear regulatory pathways, and convincing competitive landscapes [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Characteristics | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dbh-Cre Mouse Line | Enables targeted genetic access to catecholaminergic neurons | Expresses Cre recombinase under dopamine β-hydroxylase promoter | Specific manipulation of VLM-CA neurons in torpor studies [6] |

| DREADD Vectors (AAV-DIO-hM4Di/hM3Dq) | Chemogenetic neuronal manipulation | Cre-dependent; design receptor activated by CNO | Bidirectional control of neuronal activity in energy balance circuits [6] |

| Telemetry Temperature Sensors | Continuous physiological monitoring | Implantable abdominal probes; continuous data recording | Monitoring core body temperature dynamics during torpor [6] |

| Work-for-Food Paradigm System | Investigate energy balance-behavior relationships | Programmable wheel-running to food reward ratio | Studying nocturnal-diurnal switching in response to energy deficit [7] |

| Metabolic Chamber Systems | Comprehensive energy expenditure assessment | Measures O2 consumption, CO2 production, respiratory exchange ratio | Quantifying metabolic rate changes during torpor and feeding states [6] |

Visualization of Neural Circuits and Experimental Approaches

VLM-CA Neuron Circuit in Torpor Regulation

Torpor Induction Pathway: This diagram illustrates how VLM-CA neurons coordinate fasting-induced torpor through distinct projections to cardiovascular and thermoregulatory centers.

Experimental Workflow for Torpor Research

Torpor Investigation Methodology: This workflow outlines the integrated experimental approach combining physiological monitoring, molecular biology, and interventional techniques.

The neural circuits governing energy balance from hunger to torpor represent sophisticated control systems that maintain metabolic homeostasis through distributed networks spanning brainstem, hypothalamic, and limbic structures. Neural engineering interfaces provide increasingly powerful tools to map, manipulate, and model these circuits, revealing both their architectural principles and operational dynamics. The continued integration of advanced computational approaches, precise circuit manipulation tools, and human-centered design principles promises to accelerate the translation of this knowledge into therapeutic interventions for metabolic disorders, energy balance dysregulation, and conditions requiring controlled hypometabolism.

The brain-body axis serves as a fundamental conductor of organismal physiology, enabling bi-directional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral tissues. This cross-talk is particularly crucial for regulating immune responses during sickness, injury, and stress [12]. The brain must tightly control inflammation to preserve the viability of largely non-regenerative neurons while still mounting an effective defense against pathogens [12]. Essential to this process is the function of microglial cells, the resident immune cells of the brain that comprise 10-12% of all brain cells and are particularly concentrated in regions such as the hippocampus, hypothalamus, basal ganglia, and substantia nigra [12]. Under physiological conditions, healthy neurons actively maintain microglia in a quiescent state through secreted and membrane-bound signals including CD200 and CX3CL1 (fractalkine) [12]. However, both aging and stress can compromise this normal neuronal control of microglial reactivity, decreasing the brain's resiliency to inflammatory insults and creating a primed or sensitized microglial state [12]. Recent research has revealed that a body-brain circuit informs the brain of emerging inflammatory responses and allows the brain to tightly modulate the course of peripheral immune reactions [13]. Understanding these communication pathways offers new possibilities for modulating a wide range of immune disorders, from autoimmune diseases to cytokine storm and shock [13].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Brain-Body Communication

Communication Pathways in Neuroimmune Signaling

The bi-directional communication between the immune system and central nervous system is critical for mounting appropriate immunological, physiological, and behavioral responses to infection and injury [12]. The innate immune system serves as the host's first line of defense, with innate immune cells detecting potential insults via pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize and respond to both infectious elements and endogenous danger signals induced by tissue damage [12]. Upon activation, these cells synthesize and release cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) that serve as major mediators of the immune response [12].

Peripheral cytokines access the brain and induce sickness behavior through several established mechanisms [12]:

- Active transport mechanisms or diffusion at circumventricular organs where blood vessels lack a functional blood-brain barrier

- Induction of inflammatory mediators from brain endothelial cells that propagate the immune signal within the brain

- Neural pathways via the afferent vagus nerve that transmit signals to the CNS when stimulated by peripheral cytokines

The Role of Microglia in CNS Homeostasis and Inflammation

Microglia in the healthy adult brain exist in a quiescent or "resting" state characterized by a small soma and long, thin ramified processes [12]. Despite being termed "resting," these cells are highly active, continuously scanning the CNS microenvironment with estimates that the complete brain parenchyma is monitored every few hours [12]. When activated by inflammatory stimuli, microglia undergo morphological transformation with shorter, stouter processes and larger soma size, upregulate cell surface molecules including major histocompatibility markers, and release immune mediators that coordinate both innate and adaptive immune responses [12].

Table 1: Microglial States in Health and Disease

| State | Morphology | Surface Markers | Cytokine Profile | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting (Quiescent) | Small soma, ramified processes | Low MHC expression | Minimal cytokine production | Continuous tissue surveillance, homeostasis maintenance |

| Activated (Physiological) | Deramified, larger soma | Increased MHC I/II, cytokine receptors | Controlled pro-inflammatory release | Host defense, tissue repair, debris clearance |

| Primed (Sensitized) | Intermediate activation | Upregulated MHCII | Minimal basal production, exaggerated response to stimulus | Heightened readiness, associated with aging/stress |

| Chronic Activation | Amoeboid morphology | Sustained high MHC | Prolonged pro-inflammatory release | Neurotoxicity, tissue damage |

The magnitude of microglial activation is influenced by the type and duration of the stimulus, the current CNS microenvironment, and exposure to prior and existing stimuli [12]. While microglial activation is necessary for host defense and neuroprotection, increased or prolonged activation can have detrimental and neurotoxic effects [12]. Healthy neurons maintain microglia in their resting state via multiple signaling mechanisms, and a reduction in these regulatory factors can lead to a reactive microglia phenotype [12].

Quantitative Proteomic Landscape of Neuronal Development

Advanced proteomic approaches have revealed extensive remodeling of the neuronal proteome during differentiation, which shapes how neurons communicate and respond to signals. A comprehensive quantitative analysis of hippocampal neurons identified 1,793 proteins (approximately one-third of all 4,500 proteins quantified) that undergo more than 2-fold expression changes during neuronal differentiation [14]. This substantial reprogramming indicates the dynamic nature of neuronal development. Unsupervised fuzzy clustering of significantly changing proteins revealed six distinct expression profiles, with clusters 1-3 containing upregulated proteins and clusters 4-6 containing downregulated proteins during differentiation [14].

Table 2: Key Proteomic Changes During Neuronal Differentiation

| Developmental Stage | Days In Vitro | Key Biological Processes | Representative Protein Changes | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axon Formation | DIV1 (Stage 2-3) | Cell cycle exit, initial polarization | Downregulation of DNA replication factors (Mcm2-7, Pold2) | Establishment of post-mitotic state, neuronal commitment |

| Dendrite Outgrowth | DIV5 (Stage 4) | Dendritic arborization, adhesion | Upregulation of NCAM1, actin-binding proteins | Formation of neuronal connections, network formation |

| Synapse Maturation | DIV14 (Stage 5) | Synaptogenesis, network refinement | Upregulation of synaptic proteins, neurotransmitter receptors | Functional network establishment, plasticity |

This quantitative map of neuronal proteome dynamics highlights the stage-specific protein expression patterns that underlie various neurodevelopmental processes [14]. In particular, the neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM1 was found to be strongly upregulated during dendrite outgrowth, where it stimulates dendritic arbor development by promoting actin filament growth at the dendritic growth cone [14]. Such developmental changes establish the fundamental capacity of neurons to participate in brain-body communication throughout the lifespan.

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Identifying Neural Circuits Regulating Inflammation

Recent research has identified specific neural circuits that regulate body inflammatory responses through sophisticated experimental approaches [13]. The fundamental methodology involves:

Immune Challenge and Neural Activity Mapping:

- Immune stimulation: Intraperitoneal injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to elicit innate immune responses

- Neural activity monitoring: Screening brains for induction of the immediate early gene Fos as a proxy for neural activity

- Circuit identification: Identifying activated brain regions through immunohistochemistry and in vivo imaging

Functional Validation Approaches:

- Genetic silencing: Using Cre-dependent Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) to inhibit specific neuronal populations

- Circuit activation: Employing excitatory DREADDs to activate identified pathways

- Pathway interruption: Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy to disrupt body-to-brain signaling

Cell-Type Specific Characterization:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing: Profiling 4,008 cells from the caudal nucleus of the solitary tract (cNST) to identify distinct neuronal populations

- Genetic targeting: Using Vglut2-cre and Vgat-cre mice to selectively manipulate glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons

- Marker identification: Identifying dopamine β-hydroxylase (Dbh) as a candidate marker for inflammation-regulating neurons

Diagram 1: Neural Circuit Regulating Peripheral Inflammation. This diagram illustrates the body-brain circuit identified through LPS challenge experiments, showing the pathway from peripheral immune activation to brainstem processing and back to immune regulation, including key experimental interventions [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Neuroimmune Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Category | Function in Experiments | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Immune activator | Canonical immune stimulus derived from Gram-negative bacteria | Elicit innate immune responses for studying neuroimmune activation [13] |

| DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) | Chemogenetic tool | Genetically engineered receptors that modulate neuronal activity when bound by inert ligands | Selective activation or inhibition of specific neural populations in body-brain circuits [13] |

| GCaMP6s | Neural activity indicator | Genetically encoded calcium indicator for monitoring neural activity | Record real-time neuronal responses in awake behaving animals using fiber photometry [13] |

| TRAP (Targeted Recombination in Active Populations) | Genetic labeling system | Labels actively firing neurons with Cre-recombinase for subsequent manipulation | Permanent genetic access to neurons activated during specific stimuli or behaviors [13] |

| scRNA-seq (Single-cell RNA sequencing) | Transcriptomic profiling | Measures gene expression at single-cell resolution | Identify distinct cell types and states in neural circuits; characterized 4,008 cNST cells [13] |

Dysregulated Cross-Talk in Aging and Stress

Both aging and stress shift the CNS microenvironment toward a pro-inflammatory state characterized by increased microglial reactivity and reduced anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory factors [12]. During normal aging, the brain microenvironment develops chronic low-level inflammation with microglial priming - a sensitized state where microglia reside in an intermediate activation state characterized by morphological deramification and upregulation of cell surface markers like MHCII, but with minimal basal production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [12]. When additional immune challenges occur, these primed microglia respond with pronounced and prolonged release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, shifting the response from physiological to pathological [12].

Stress-induced disruption of normal neuronal-microglial communication leads to aberrant central immune responses when additional stressors are applied [12]. The concurrent decline in normal function of both neurons and microglia during aging contributes to dysfunctional interactions under inflammatory conditions [12]. This dysregulated cross-talk creates a vulnerable brain state with reduced resiliency to inflammatory insults.

Diagram 2: Dysregulated Neuronal-Microglial Cross-Talk in Aging and Stress. This diagram illustrates how aging and stress disrupt normal communication between neurons and microglia, leading to a primed microglial state that responds excessively to subsequent immune challenges [12].

Implications for Neural Engineering and Therapeutic Development

The growing understanding of brain-body communication mechanisms opens new avenues for neural engineering approaches to modulate these pathways for therapeutic benefit. Key implications include:

Bioelectronic Medicine:

- Targeted neuromodulation of identified body-brain circuits could potentially suppress pro-inflammatory responses while enhancing anti-inflammatory states

- Closed-loop systems might detect early inflammatory changes and deliver precise neural stimulation to rebalance immune function

- Selective interface technologies could enable precise targeting of specific neural populations identified through scRNA-seq characterization

Diagnostic and Monitoring Applications:

- Neural interface technologies could monitor activity in body-brain circuits to assess inflammatory states and disease progression

- Biomarker development based on identified molecular signatures (e.g., DBH-positive neurons) could guide therapeutic targeting

- Circuit-specific readouts may enable early detection of dysregulated neuroimmune communication before overt pathology develops

The revelation that brain-evoked transformation can effectively change the course of an immune response offers new possibilities for modulating a wide range of immune disorders [13]. Rather than targeting individual immune molecules or cells, therapeutic approaches that engage the natural body-brain circuit for immune regulation may provide more balanced and system-wide effects with reduced side effects.

The intricate cross-talk between the brain and body represents a fundamental regulatory system for maintaining health and responding to challenges. The neural mechanisms mediating these communications during sickness, injury, and stress involve precisely coordinated signaling pathways that inform the brain of peripheral immune status and allow the brain to shape appropriate immune responses. Disruption of these communication pathways during aging and stress creates vulnerability to excessive inflammation and neurological complications. Emerging technologies in neural engineering offer promising approaches to interface with these natural regulatory systems, potentially leading to novel therapeutic strategies for a wide range of inflammatory and neurological conditions. As our understanding of these mechanisms grows, so too does our ability to develop targeted interventions that restore balance to the brain-body axis.

The pursuit of effective treatments for neurological disorders faces a significant challenge: the translational gap between discoveries in conventional animal models and their application in human patients. While rodents have been indispensable to basic neuroscience research, many aspects of human brain organization, circuit complexity, and neurodegenerative disease pathology are poorly replicated in these distant phylogenetic relatives [15]. Neural engineering, which aims to develop technologies for understanding, repairing, and enhancing neural systems, requires models that faithfully recapitulate human neurobiology to ensure these innovations translate successfully to clinical applications [3]. The gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus), a small, nocturnal primate, has emerged as a promising translational model that occupies a unique evolutionary position between rodents and humans, offering unprecedented opportunities for bridging this gap [16] [17]. This whitepaper examines the biological rationale, experimental resources, and methodological approaches for utilizing the mouse lemur as a model system for human-relevant neurological insights within the context of neural engineering research.

Table: Key Characteristics of the Gray Mouse Lemur as a Neural Model

| Feature | Specification | Advantage for Neural Research |

|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Position | Primate (Strepsirrhine) | Closer to humans than rodents; shares primate-specific neural features [15] |

| Body Size | 60-120 grams | Practical for laboratory settings; reduced housing costs [18] |

| Lifespan | 8-12 years in captivity | Enables longitudinal aging studies [18] |

| Brain Features | Primate-like organization with cortical specialization | Includes features like granular prefrontal cortex and layered LGN absent in rodents [17] |

| Reproductive Maturity | 8-10 months | Permits rapid colony expansion compared to larger primates [19] |

The Mouse Lemur as a Primate Model System

Evolutionary Position and Practical Advantages

The mouse lemur occupies a strategic phylogenetic position as a primate that diverged early in primate evolution, providing a crucial evolutionary link for comparative neuroscience [16]. As a primate, mouse lemurs share homologous brain organization with humans, including specialized motor, perceptual, and cognitive abilities not found in rodents [15]. This evolutionary proximity translates to significant advantages for modeling human neurological conditions, particularly age-related neurodegenerative disorders where rodent models have shown limited predictive validity.

Despite their phylogenetic sophistication, mouse lemurs retain practical advantages typically associated with traditional animal models. Their small body size (approximately 12 cm body length, 60-120 g), relatively short lifespan (approximately 12 years), and rapid maturity (reaching reproduction in their first year) make them logistically and economically feasible for laboratory research [18]. These characteristics enable researchers to maintain substantial colonies at lower costs compared to larger primate species while still studying age-related neurological changes over a tractable timeframe. Furthermore, mouse lemurs exhibit marked seasonal rhythms in response to photoperiod changes, providing an natural system for investigating how environmental factors influence neural function and aging [18].

Neurobiological Similarities to Humans

Mouse lemurs exhibit several neuroanatomical features that closely resemble those of humans and are absent in rodents. These include:

- Cortical folding with a distinct layer IV in the frontal cortex, suggesting the presence of a granular prefrontal cortex comparable to that of higher primates [17]

- Segregated basal ganglia nuclei with caudate and putamen separated by a distinct fiber tract, unlike the fused striatum of rodents [17]

- Layered lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) exhibiting a distinct six-layered structure for sophisticated visual information processing [17]

- Sublaminated primary visual cortex with layer IV divided into IVa and IVb, a characteristic unique to primates that is also observed in mouse lemurs [17]

These specialized neuroanatomical features make the mouse lemur particularly valuable for studying neural circuits and systems that are specifically relevant to human brain function and dysfunction. The presence of these primate-specific characteristics enables more accurate mapping of neural circuits and testing of neuromodulation technologies being developed in the neural engineering field [17].

Applications in Aging and Neurodegenerative Disease Research

Modeling Age-Related Cognitive Decline

The mouse lemur naturally develops age-related cognitive impairments that closely mirror those observed in human aging. Research has demonstrated that aged mouse lemurs show deficits in retention capacity and new object memory, while largely preserving the ability to form simple stimulus-reward associations [15]. Crucially, these animals exhibit high interindividual variability in cognitive aging, with some individuals maintaining cognitive function into advanced age while others show significant decline—a pattern that closely mimics human cognitive aging [15]. This variability provides a fruitful background for exploring discriminant cognitive markers and investigating the neural correlates of normal versus pathological aging.

Several behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) analogous to those in humans have been identified in aging mouse lemurs. These include alterations in locomotor activity rhythms, increased fragmentation of sleep-wake cycles, and increased activity during the normal resting phase [15]. Additionally, studies have established a correlation between glucose homeostasis impairment and cognitive deficits in middle-aged mouse lemurs, replicating the established relationship between type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative risk in humans [15]. These convergent pathophysiological mechanisms significantly enhance the translational potential of findings from this model.

Alzheimer's Disease Pathology

Mouse lemurs spontaneously develop cerebral alterations that closely resemble the neuropathological features of Alzheimer's disease in humans. Aged lemurs have been shown to accumulate amyloid beta protein in their brains and develop senile plaques with morphological and immunological properties similar to those found in Alzheimer's patients [18]. Additionally, researchers have identified the presence of apolipoprotein E alleles and presenilin proteins in mouse lemurs that are molecularly similar to those implicated in human Alzheimer's disease [18].

The spontaneous development of these Alzheimer's-like neuropathological features in a primate model provides a unique opportunity to study the natural progression of neurodegenerative processes and test potential interventions in a biologically relevant system. The presence of these pathological hallmarks, combined with the observed cognitive deficits, positions the mouse lemur as a valuable model for investigating disease mechanisms and evaluating novel therapeutic approaches, including neural engineering applications aimed at restoring cognitive function.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Animal Models for Neuroscience Research

| Characteristic | Mouse Model | Mouse Lemur Model | Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic Distance | ~75 million years [15] | ~55 million years [15] | - |

| Frontal Cortex Organization | Agranular or dysgranular | Granular prefrontal cortex [17] | Granular prefrontal cortex |

| Striatal Organization | Fused striatum | Segregated caudate/putamen [17] | Segregated caudate/putamen |

| Lateral Geniculate Nucleus | Non-layered | Six-layered structure [17] | Six-layered structure |

| Amyloid Plaque Formation | Requires genetic manipulation | Spontaneous in aging [18] | Spontaneous in aging & AD |

| Interindividual Cognitive Variability | Limited | High, human-like [15] | High |

Cellular and Molecular Insights from Recent Advances

The Tabula Microcebus Cell Atlas

Recent groundbreaking research from the Tabula Microcebus Consortium has generated a comprehensive cell atlas of the mouse lemur, profiling nearly 780,000 cells from 12 different brain regions and comparing them with equivalent data from humans, macaques, and mice [16] [20]. This landmark study, published in Nature, identified both conserved and divergent characteristics in brain cell function across species and revealed a specific cell type found only in primates [16]. The atlas provides critical insight into the architecture of primate brains and establishes the mouse lemur as a model not only for evolutionary neuroscience but also for studying brain development, aging, and disease.

The molecular cell atlas encompasses 226,000 cells from 27 mouse lemur organs, defining more than 750 molecular cell types and their full gene expression profiles [20]. This resource includes cognates of most classical human cell types, including stem and progenitor cells, and reveals dozens of previously unidentified or sparsely characterized cell types. Comparative analysis demonstrated cell-type-specific patterns of primate specialization and identified many cell types and genes for which the mouse lemur provides a better human model than mouse [20]. This comprehensive molecular foundation enables researchers to identify appropriate cellular targets for neural engineering applications and understand how neuromodulation technologies might affect specific cell populations in the primate brain.

The eLemur 3D Digital Brain Atlas

Complementing the molecular atlas, researchers have developed eLemur, a comprehensive three-dimensional digital brain atlas providing cellular-resolution data on the mouse lemur brain [17]. This resource comprises a repository of high-resolution brain-wide images immunostained with multiple cell type and structural markers, elucidating the cyto- and chemoarchitecture of the mouse lemur brain. The atlas includes a segmented reference delineated into cortical, subcortical, and other vital regions, along with a comprehensive 3D cell atlas providing densities and spatial distributions of neuronal and non-neuronal cells [17].

The eLemur atlas is accessible via a web-based viewer (https://eeum-brain.com/#/lemurdatasets), streamlining data sharing and integration and fostering the exploration of different hypotheses and experimental designs [17]. This openly accessible resource significantly lowers the barrier to entry for researchers interested in utilizing the mouse lemur model. The compatibility of eLemur with existing neuroanatomy frameworks and growing repositories of 3D datasets for rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans enhances its utility for comparative analysis and translation research, facilitating the integration of extensive rodent study data into human studies [17].

Experimental Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Atlas Generation Workflow

The creation of comprehensive brain atlases for the mouse lemur involves sophisticated methodological pipelines that integrate multiple experimental and computational approaches. The workflow for generating the eLemur atlas exemplifies this integrated approach, beginning with whole-brain sectioning accompanied by block face imaging for subsequent registration of immunofluorescence images [17]. This is followed by brain-wide multiplex immunolabeling using carefully selected markers that delineate brain structures, axonal projections, and cell types compatible with mouse lemur brain tissue.

Key markers used in these analyses include:

- NeuN and DAPI for neuronal and non-neuronal populations

- Parvalbumin (PV) for specific inhibitory neuron subtypes

- Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) for characterizing basal ganglia and dopaminergic pathways

- VGLUT2 and myelin basic protein (SMI-99) for differentiating subregional structures [17]

Following staining, high-resolution fluorescence imaging is performed, with combinatorial multiplex immunofluorescence datasets achieving resolutions of 0.65 μm in x-y dimensions. Subsequent computational processing includes image alignment, cell detection analysis, and 3D atlas generation, culminating in the implementation of an interactive web-based visualization platform that makes these resources accessible to the broader research community [17].

Cognitive and Behavioral Assessment

Well-established behavioral paradigms have been adapted for assessing cognitive function in mouse lemurs, focusing on domains relevant to human neurological disorders. These cognitive tasks cover major cognitive domains including recognition, spatial and working memories, stimulus reward associative learning, and set-shifting performances [15]. The specific protocols include:

- Spatial memory tasks utilizing maze paradigms to assess reference spatial memory

- Object recognition tests evaluating the ability to form and retain memories of novel objects

- Generalization and spatial rule-guided discrimination tasks testing executive function and cognitive flexibility

- Circadian rhythm monitoring using automated activity tracking systems to quantify disruptions in sleep-wake cycles [15]

These behavioral assessments are particularly valuable when combined with neuroimaging techniques such as MRI and histopathological analyses, enabling researchers to establish correlations between cognitive performance and neurobiological changes. The identification of individuals with natural genetic variants affecting neurological function further enhances the utility of this model for connecting specific molecular changes to behavioral outcomes [19].

Key Research Reagents and Platforms

Table: Essential Research Resources for Mouse Lemur Neuroscience

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Markers | NeuN, DAPI, Parvalbumin, Tyrosine Hydroxylase, VGLUT2, SMI-99 [17] | Cell type identification, cytoarchitectural mapping, neural circuit tracing |

| Genomic Resources | M. murinus reference genome, single-cell RNA sequencing protocols [20] | Evolutionary comparisons, molecular profiling, genetic variant analysis |

| Digital Atlases | eLemur 3D digital brain atlas (https://eeum-brain.com/#/lemurdatasets) [17] | Anatomical reference, data integration, comparative analysis |

| Cell Atlases | Tabula Microcebus (226,000 cells from 27 organs) [20] | Cell type identification, molecular profiling, cross-species comparison |

Experimental Considerations

When designing studies using the mouse lemur model, researchers should consider several methodological factors to ensure robust and reproducible results. The seasonal biology of mouse lemurs necessitates careful consideration of photoperiod conditions in experimental design, as physiological parameters can vary significantly between long and short day periods [18]. Additionally, the interindividual variability in cognitive aging patterns requires sufficiently large sample sizes to account for different aging trajectories when studying age-related neurological changes [15].

For neural engineering applications specifically, the primate-specific neuroanatomical features of the mouse lemur brain—including its segregated basal ganglia nuclei and specialized cortical organization—may necessitate adaptations to devices and algorithms developed in rodent models [17]. However, these same features provide opportunities to test neural interfaces in a system that more closely approximates human neuroanatomy before advancing to clinical trials. The availability of detailed anatomical and molecular reference atlases enables precise targeting of neural stimulation and recording sites, facilitating the development of more effective neuromodulation strategies [17] [20].

The mouse lemur represents a transformative model system that combines practical advantages with significant neurobiological relevance to humans. Its phylogenetic position, neuroanatomical specialization, natural development of age-related neurological changes, and growing molecular and anatomical resource base position it as an ideal platform for advancing human-relevant neurological insights. For the neural engineering field, this model offers particular promise for bridging the gap between rodent studies and human applications, enabling testing of neuromodulation technologies, brain-computer interfaces, and neuroprosthetic devices in a system that shares key neural features with humans [3] [17].

The ongoing development of comprehensive research resources—including cellular atlases, genomic data, and digital brain maps—is lowering barriers to adoption and facilitating the integration of mouse lemur studies into mainstream neuroscience research [17] [20]. As neural engineering continues to advance toward more sophisticated interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders, the availability of a practical, physiologically relevant primate model will be increasingly valuable for validating technologies and ensuring their successful translation to clinical practice. The mouse lemur model thus represents not only a novel experimental system but also a critical bridge between basic neuroscience discovery and applied neural engineering innovation.

Toolkit for the Mind: Methodological Breakthroughs and Clinical Applications of Neurotechnology

The brain-computer interface (BCI) represents a transformative technology in neural engineering, creating a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the complete BCI pipeline, from signal acquisition through processing to closed-loop execution. Within the broader context of how neural engineering interfaces with the nervous system, we analyze the technical specifications, methodological considerations, and performance metrics of each pipeline component. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning has substantially advanced the decoding of neural signals, enabling more sophisticated applications in neurorehabilitation, cognitive assessment, and therapeutic intervention. This technical guide serves researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand the engineering principles and experimental protocols underlying modern BCI systems.

Neural engineering is an interdisciplinary field that combines principles from neuroscience, engineering, computer science, and mathematics to study, repair, replace, or enhance neural systems [3]. It aims to understand nervous system function, develop technologies to interact with it, and create devices that can restore or improve neural function. Brain-computer interface technology represents one of the most direct applications of neural engineering, enabling communication between the brain and external devices without relying on the brain's normal output pathways of peripheral nerves and muscles [21].

The conceptual foundation for BCI was first articulated by Jacques Vidal in 1973, and the field has since evolved from basic proof-of-concept systems to sophisticated platforms with clinical applications [21]. The efficacy of BCI systems depends fundamentally on advances in signal acquisition methodologies and processing algorithms [21]. Modern BCI systems show particular promise for addressing neurological disorders, with applications emerging in neurorehabilitation, cognitive assessment, and assistive technologies for conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), locked-in syndrome (LIS), spinal cord injury (SCI), and stroke [22] [23].

Table 1: Key Neural Engineering Technologies Relevant to BCI

| Technology | Primary Function | Clinical/Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) | Direct communication between brain and external devices | Prosthetic control, communication systems for paralyzed patients |

| Neuroprosthetics | Replacement or enhancement of damaged neural systems | Cochlear implants, retinal implants |

| Neural Signal Processing | Analysis and interpretation of nervous system signals | Brain state decoding, feature extraction for BCI control |

| Neuromodulation | Modulation of neural activity using external stimuli | Deep brain stimulation (DBS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) |

| Neural Tissue Engineering | Creation of biological substitutes for neural tissue | Stem cell therapies, biomaterial scaffolds for nerve regeneration |

A typical BCI system comprises four fundamental components that form a complete processing pipeline: (1) signal acquisition, (2) signal processing (including preprocessing, feature extraction, and feature selection), (3) classification and translation algorithms, and (4) output with feedback to create closed-loop systems [21] [22]. This pipeline enables the translation of brain activity into commands for external devices, with the "closed-loop" aspect allowing for real-time data to monitor and adjust outputs based on the user's condition [22].

Figure 1: The complete BCI pipeline illustrates the sequential stages from neural signal acquisition to closed-loop execution, with feedback influencing subsequent neural activity.

Signal Acquisition Technologies

Signal acquisition constitutes the critical first stage of the BCI pipeline, with the detection and recording of cerebral signals directly determining system effectiveness [21]. The classification of signal acquisition technologies can be understood through a two-dimensional framework encompassing surgical invasiveness and sensor operating location [21].

Surgical Dimension: Invasiveness of Procedures

The surgical dimension classifies BCI approaches based on the invasiveness of the procedure required for signal acquisition, ranging from non-invasive to minimally invasive and fully invasive techniques [21].

Non-invasive Methods: These approaches require no surgical intervention and do not cause anatomically discernible trauma. Electroencephalography (EEG) is the most prominent example, recording electrical activity along the scalp. EEG provides a practical balance of signal quality, cost, and safety, though it offers limited spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio compared to more invasive methods [21] [23].

Minimally Invasive Methods: These techniques cause anatomical trauma that spares brain tissue itself. Examples include vascular stent electrodes that leverage naturally existing cavities like blood vessels, and electrocorticography (ECoG), which involves placing a thin plastic pad of electrodes right above the brain's cortex [21] [23].

Invasive Methods: These approaches cause anatomically discernible trauma at the micron scale or larger to brain tissue. Microelectrode arrays implanted directly into gray matter fall into this category. While offering the highest signal quality, they present greater surgical risks and ethical considerations [21].

Detection Dimension: Sensor Operating Location

The detection dimension classifies BCIs based on where sensors operate during signal acquisition, which directly influences the theoretical upper limit of signal quality [21].

Non-implantation: Sensors remain on the body surface, as with EEG. This approach is analogous to "listening to a chorus from outside the building," where only large-scale sums of neuronal activity can be detected amid noise [21].

Intervention: Sensors leverage naturally existing cavities within the body, such as blood vessels, without harming the integrity of original tissue. Stent-based electrodes are an emerging technology in this category [21].

Implantation: Sensors are placed within human tissue, as with intracortical microelectrodes. These typically provide the highest signal quality but raise biocompatibility concerns and may become integrated with tissue over time, complicating removal [21].

Table 2: Comparison of BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Technology | Surgical Dimension | Detection Dimension | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Signal Quality | Clinical Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Non-invasive | Non-implantation | Low (cm) | High (ms) | Low | Minimal |

| MEG | Non-invasive | Non-implantation | Medium | High | Medium | Minimal |

| ECoG | Minimally Invasive | Implantation | High (mm) | High | Medium-High | Moderate |

| Strode Arrays | Invasive | Implantation | High (μm) | High | High | Significant |

| Stent Electrodes | Minimally Invasive | Intervention | Medium-High | High | Medium-High | Moderate |

Signal Preprocessing and Cleaning

Raw neural signals, particularly from non-invasive approaches like EEG, contain substantial noise and artifacts that must be addressed before meaningful analysis can occur. Preprocessing transforms raw data into cleaned signals suitable for feature extraction [24].

Experimental Protocol: EEG Preprocessing Pipeline

A standardized preprocessing protocol for EEG data involves sequential steps to address different types of noise and artifacts:

Data Importation: EEG data is typically acquired in standardized formats such as FIF (Functional Imaging File Format) or EDF (European Data Format), which can be processed using libraries like MNE-Python [24].

Bad Channel Identification and Interpolation: Visual inspection or automated algorithms identify malfunctioning electrodes. Spherical spline interpolation estimates missing data based on surrounding good channels [24].

Filtering: Multiple filtering techniques isolate signals of interest:

- High-pass filtering (cutoff ~0.1 Hz) removes slow drifts and DC offsets

- Low-pass filtering (cutoff ~30 Hz for cognitive tasks) removes high-frequency noise

- Notch filtering (50/60 Hz) eliminates power line interference [24]

Downsampling: Data sampling rates are reduced to decrease computational load while maintaining signal integrity according to the Nyquist-Shannon theorem [24].

Re-referencing: Electrode signals are recomputed against different reference schemes (e.g., linked mastoids, average reference) to improve signal interpretation [24].

Optimization of Preprocessing Parameters

Preprocessing stage optimization must balance accuracy and computational timing costs, particularly for real-time BCI applications. Research demonstrates that parameter optimization in the preprocessing stage can significantly impact final classification performance [25].

Table 3: Preprocessing Stage Optimization Results for Motor Imagery BCI

| Preprocessing Parameter | Options | Optimal for Accuracy | Optimal for Timing Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Interval | 0-2s, 0-3s, 0-4s, 0-5s | 0-4s | 0-2s |

| Time Window - Step Size | 2s-0.125s, 1s-0.125s, 0.5s-0.125s, 2s-0.5s | 2s-0.125s | 0.5s-0.125s |

| Theta Band (4-7 Hz) | Included, Not Included | Included | Not Included |

| Mu/Beta Band (8-30 Hz) | Included, Not Included | Included | Not Included |

Taguchi method optimization with Grey relational analysis has demonstrated that the highest accuracy performance is obtained with a 0-4s time interval, 2s window with 0.125s step size, and inclusion of both theta and mu/beta frequency bands [25].

Feature Extraction and Selection

Feature extraction transforms preprocessed signals into representative characteristics that capture essential patterns of underlying brain activity, reducing data dimensionality while highlighting relevant information [24].

Feature Extraction Methodologies

Time-Domain Features: These capture temporal signal characteristics, including amplitude measurements (peak-to-peak, mean, variance), latency metrics (onset latency, peak latency), and time-series analysis techniques (autoregressive models, moving averages) [24].

Frequency-Domain Features: These analyze power distribution across frequency bands, with Power Spectral Density (PSD) calculated using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and band power computations for standard frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma) [24].

Time-Frequency Features: Techniques like Wavelet Transform and Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) capture dynamic changes in frequency content over time, particularly useful for analyzing non-stationary signals [24].

Feature Selection Algorithms

Feature selection identifies the most informative characteristics from extracted features to improve model performance and avoid overfitting [26].

Filter Methods: Select features based on intrinsic characteristics independent of the machine learning algorithm. Variance Thresholding removes low-variance features, while SelectKBest chooses top features based on statistical tests like ANOVA F-value [26].

Wrapper Methods: Evaluate feature subsets by training and testing models with each subset. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) iteratively removes less important features based on classifier performance [26].

Embedded Methods: Incorporate feature selection during model training. L1 Regularization (LASSO) adds a penalty term that drives weights of less important features toward zero [26].

Advanced optimization algorithms like the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) have demonstrated exceptional performance for feature selection in BCI systems, achieving accuracy up to 98.6% when combined with k-NN classifiers for motor imagery tasks [23].

Classification Algorithms and Translation

Classification algorithms translate selected features into device commands, serving as the final decoding stage in the BCI pipeline [26].

Machine Learning Approaches

Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): A classic linear classification method that finds projections maximizing separation between classes. LDA offers simplicity, speed, and effectiveness for high-dimensional BCI data [26] [23].

Support Vector Machines (SVM): Construct optimal hyperplanes to separate different classes in feature space. Kernel functions (linear, polynomial, radial basis function) enable handling of non-linear decision boundaries [26] [23].

Other Classifiers: Various algorithms offer different trade-offs, including Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Random Forests, and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) [26] [23].

Deep Learning and Optimization

Deep learning approaches have shown increasing promise for BCI applications, with optimized architectures demonstrating significant performance improvements. Bayesian optimization for hyperparameter tuning in deep learning models has achieved 4-9% accuracy improvements over conventional classifiers [27].

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Classification Algorithms for Motor Imagery BCI

| Classification Algorithm | Average Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | 70-85% | Fast, simple, works well with high-dimensional data | Limited to linear decision boundaries |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 75-90% | Handles non-linearity via kernels, effective in high dimensions | Sensitivity to parameter tuning |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) | 80-92% | Simple, no training phase, naturally handles multi-class | Computationally intensive during execution |

| Random Forest | 78-90% | Handles non-linearity, robust to overfitting | Less interpretable, more parameters to tune |

| Optimized Deep Learning | 85-98% | Automatic feature learning, high performance | Computationally intensive, requires large data |

Closed-Loop Systems and Output

The closed-loop aspect represents the culmination of the BCI pipeline, where system outputs provide feedback to users, creating an adaptive interface that responds to brain activity in real time [22].

Feedback Mechanisms

Feedback components inform users about the computer's interpretation of their intended actions, typically conveyed through visual, auditory, or tactile modalities. This feedback enables adjustments and supports the closed-loop design essential for effective BCI operation [21].

Real-World Applications

Neurorehabilitation: BCI closed-loop systems facilitate recovery for patients with strokes, head trauma, and other neurological disorders by promoting neuroplasticity through real-time feedback [22] [3].

Assistive Technologies: These systems enable control of external devices such as prosthetic limbs, wheelchairs, or communication interfaces for individuals with motor impairments [23].

Cognitive Monitoring: BCIs integrated with AI allow for real-time monitoring of cognitive states, with particular relevance for conditions like Alzheimer's disease and related dementias [22].

Neuromorphic Engineering Approaches

Emerging neuromorphic engineering approaches implement closed-loop BCI systems using brain-inspired computing architectures. These systems offer potential advantages in power efficiency and real-time processing for adaptive brain interfaces [28].

Figure 2: Closed-loop BCI system with adaptive algorithms that adjust acquisition and processing parameters based on feedback, optimizing system performance over time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential Research Materials for BCI Development and experimentation

| Item | Specification/Example | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Recording System | Biosemi ActiveTwo, BrainVision, g.tec systems | Multi-channel electrophysiological data acquisition |

| Electrodes/Caps | Ag/AgCl electrodes, electrode caps with 32-256 channels | Signal transduction from scalp to recording system |

| Electrode Gel | Electro-Gel, Signa Gel, Ten20 conductive paste | Maintains conductivity between scalp and electrodes |

| Data Processing Software | MNE-Python, EEGLAB, BCILAB | Signal preprocessing, analysis, and visualization |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implementation of classification algorithms |

| Neuromodulation Devices | TMS, tDCS, neurostimulation systems | Investigate causal relationships in neural circuits |

| Implantable Electrodes | Microelectrode arrays, ECoG grids, Utah arrays | Invasive and minimally invasive signal acquisition |

| Bioamplifiers | g.tec amplifiers, Blackrock Microsystems | Signal conditioning and amplification |

The BCI pipeline represents a mature framework for creating direct interfaces between the brain and external devices, with clearly defined stages from signal acquisition to closed-loop execution. Advances in neural engineering have progressively enhanced each component of this pipeline, with current research focusing on optimizing preprocessing parameters, developing sophisticated feature selection algorithms, and implementing adaptive classification approaches. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning has been particularly transformative, enabling more accurate decoding of neural signals and creating more responsive closed-loop systems.