Pulse Wave-Driven Machine Learning for Non-Invasive Coronary Artery Calcification Detection: Validation and Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation of pulse wave analysis combined with machine learning for the non-invasive detection of coronary artery calcification, a major cardiovascular risk factor.

Pulse Wave-Driven Machine Learning for Non-Invasive Coronary Artery Calcification Detection: Validation and Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the validation of pulse wave analysis combined with machine learning for the non-invasive detection of coronary artery calcification, a major cardiovascular risk factor. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational pathophysiology linking vascular dynamics to CAC, details methodological approaches for model development including feature extraction and algorithm selection, addresses critical challenges in clinical deployment such as algorithmic bias and regulatory compliance, and evaluates performance metrics and comparative effectiveness against traditional screening methods. The content synthesizes recent 2025 clinical evidence to outline a pathway for integrating this promising, cost-effective technology into cardiovascular risk assessment pipelines.

The Pathophysiological Link Between Pulse Wave Dynamics and Coronary Calcification

Coronary Artery Calcification as a Critical Cardiovascular Risk Marker in Renal Disease

Coronary Artery Calcification (CAC) represents a particularly aggressive form of atherosclerosis that disproportionately affects individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD). The pathophysiological relationship between renal impairment and vascular calcification creates a perfect storm for cardiovascular complications. In CKD patients, traditional Framingham risk factors converge with unique uremic stressors—including hyperphosphatemia, calciprotein particle formation, and chronic inflammation—to drive accelerated calcification within coronary artery walls [1]. This process is not merely a passive precipitation of calcium phosphate but an active, cell-mediated transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells into osteoblast-like cells, culminating in profound vascular stiffness and compromised myocardial perfusion.

The clinical implications of this process are severe. Among patients with CKD, cardiovascular mortality is 10 to 30 times higher than in the general population, with CAC serving as a central pathological feature driving this excessive risk [1]. Recent evidence from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study demonstrates that CAC progression in CKD patients occurs at an accelerated rate compared to those with preserved renal function, creating an urgent need for effective detection and monitoring strategies [2] [3]. This review comprehensively compares established and emerging technologies for CAC assessment, with particular emphasis on validating pulse wave-driven machine learning approaches within the renal disease population.

Established Methods for Coronary Artery Calcification Assessment

Computed Tomography and the Agatston Score

The quantification of coronary artery calcium via computed tomography (CT) imaging remains the undisputed gold standard for CAC assessment. The Agatston score, developed in 1990, calculates CAC burden through a weighted combination of calcified plaque area and maximum density factor observed on electrocardiogram-gated non-contrast CT scans [4] [5]. Current clinical protocols typically stratify patients into risk categories based on Agatston score ranges: zero (no identifiable plaque), 1-100 (mild), 101-400 (moderate), and greater than 400 (severe calcification) [6] [5].

The prognostic power of CAC scoring is well-established in both general and renal populations. The CRIC study prospectively evaluated 1,310 CKD participants with at least one CAC scan and found that those without baseline CAC who developed incident calcification had a 2.42-fold higher rate of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (95% CI: 1.23-4.79) and 1.82-fold higher all-cause mortality (95% CI: 1.03-3.22) after multivariable adjustment [2] [3]. Similarly, patients with baseline CAC who experienced progression (defined as ≥50 Agatston units per year) demonstrated a 1.73-fold higher mortality rate (95% CI: 1.31-2.28) [2].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of CAC Detection Technologies

| Methodology | Population Studied | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-Based Agatston Scoring | 1,310 CKD patients [2] | Hazard Ratio for Mortality: 1.73-1.82 [2] | Prognostic validation; Standardized risk categories | Radiation exposure; Cost; Limited accessibility |

| AI-Automated CAC Scoring | 79 CT scans [4] | Kappa=0.89 vs manual scoring [4] | High speed (<60 sec); Elimination of inter-reader variability | Limited validation in CKD-specific populations |

| Pulse Wave ML Model (GBDT) | 58 ESRD patients [6] [7] | Accuracy=84.1%; AUC=0.962 [6] | Non-invasive; Cost-effective; Bedside application | Small sample size; Single-center design |

| Pulse Wave ML Model (SphygmoCor) | 124 CKD stage 5 patients [8] | Balanced accuracy >80% for CAC≥100 [8] | Superior to traditional risk factors in younger patients | Limited data for CKD stages 3-4 |

Artificial Intelligence in CAC Quantification

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have transformed CAC assessment from a labor-intensive manual process to an automated pipeline with emerging clinical applications. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—a deep learning architecture specifically designed for image processing—have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in automating CAC scoring on both dedicated cardiac CT and non-gated chest CT examinations performed for other indications [4].

The clinical implementation of AI-driven CAC scoring addresses several critical limitations of traditional approaches. Automated systems eliminate inter-observer variability, significantly reduce interpretation time (with processing times under 60 seconds in some implementations), and potentially enable widespread CAC screening through opportunistic detection on non-cardiac CT studies [4]. Notably, non-gated chest CT scans performed for lung cancer screening represent a particularly promising application, as this population overlaps significantly with those at intermediate to high cardiovascular risk. Unfortunately, current reporting of incidental CAC on these studies remains inconsistent, occurring in only 44-59% of cases with visible calcification [4].

Pulse Wave-Driven Machine Learning: An Emerging Paradigm

Physiological Rationale and Technical Foundations

The fundamental premise of pulse wave analysis for CAC assessment rests on the principle that progressive vascular calcification alters arterial biomechanics in measurable ways. As coronary arteries undergo calcification, parallel changes occur in systemic arterial stiffness, pulse wave velocity, and waveform morphology—all of which can be captured and quantified through peripheral pulse wave analysis [6] [8].

The pathophysiological link between CKD and altered pulse wave characteristics involves multiple interconnected pathways. Uremia-induced vascular smooth muscle cell transdifferentiation, chronic inflammation mediated by cytokines such as galectin-3 and hs-CRP, and metabolic abnormalities including hyperphosphatemia collectively drive both coronary calcification and increased arterial stiffness [1] [9]. These changes manifest in distinct pulse wave patterns characterized by attenuated tidal waves, altered diastolic decay contours, and overall waveform smoothing that correlates with CAC severity [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Recent investigations have employed standardized protocols for pulse wave data acquisition and analysis in CKD populations. In a study of 58 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients undergoing hemodialysis, radial artery pulse waveforms were recorded before, hourly during, and after hemodialysis sessions using calibrated acquisition systems [6] [7]. Participants concurrently underwent low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for CAC quantification using Agatston scoring, establishing ground truth for model development.

The feature extraction pipeline encompassed multiple pulse wave domains:

- Morphological parameters: Primary wave amplitude, tidal wave presence and amplitude, dicrotic notch position

- Temporal characteristics: Pulse wave transit time, systolic and diastolic phase intervals

- Complexity metrics: Multiscale entropy, waveform distribution characteristics

- Hemodynamic indices: Mean amplitude, ascending/descending slope characteristics [6]

Machine learning models, particularly Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithms, were then trained to classify CAC severity into four categories (none, mild, moderate, severe) based on the extracted pulse wave features. The GBDT framework was selected for its ability to model complex nonlinear relationships between pulse wave characteristics and CAC burden while providing robustness against overfitting [6] [7].

Performance Validation and Comparative Efficacy

The validated performance of pulse wave-driven machine learning models for CAC detection is compelling, particularly considering the relatively early stage of this technological approach. In the aforementioned study of ESRD patients, the GBDT model achieved an average accuracy of 84.1% with a macro-AUC of 0.962 in fivefold cross-validation, with comparable performance (83.9% accuracy, 0.961 AUC) on an independent test set [6] [7]. Notably, the model demonstrated particular proficiency in identifying severe calcification cases, which carries the greatest clinical significance for risk stratification.

A separate investigation of 124 CKD stage 5 patients evaluated a pulse wave-based classifier using the SphygmoCor system and demonstrated balanced accuracy exceeding 80% for detecting clinically significant CAC (Agatston score ≥100) [8]. This study further revealed that the pulse wave-based approach outperformed models using traditional risk factors alone, particularly among younger patients (under 50 years old), suggesting potential value for early detection in high-risk populations [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pulse Wave CAC Detection Studies

| Research Tool | Specification Purpose | Experimental Function | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Artery Pulse Wave Acquisition System | SphygmoCor (AtCor Medical) [8] or equivalent | Capture peripheral pulse waveform data at radial artery | 58 ESRD patients [6]; 124 CKD stage 5 patients [8] |

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) Algorithm | Machine learning framework | Classify CAC severity from pulse wave features | 84.1% accuracy, 0.962 AUC for CAC severity stratification [6] |

| Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) | Non-contrast, ECG-gated protocol | Reference standard for Agatston score calculation | CAC severity classification per standard categories (0, 1-100, 101-400, >400) [6] |

| Pulse Wave Feature Extraction Pipeline | Morphological, temporal, complexity domains | Quantify pulse waveform characteristics for model input | Significant variation across CAC groups and during hemodialysis [6] |

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Emerging Approaches

When evaluated against established CAC detection methodologies, pulse wave-driven machine learning demonstrates a distinct performance profile with complementary strengths and limitations. Traditional CT-based approaches provide unparalleled anatomical visualization and extensive prognostic validation across diverse populations, including robust data from the CRIC study specifically in CKD patients [2] [3]. AI-enhanced CAC scoring builds upon this foundation with improved efficiency and reproducibility while maintaining high diagnostic accuracy [4].

The pulse wave analysis paradigm sacrifices some degree of accuracy for substantial advantages in accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and practical implementation. The 84-85% accuracy demonstrated in current validation studies [6] [8] falls short of the near-perfect agreement between AI and manual CT scoring (kappa=0.89) [4]. However, the non-invasive nature, minimal cost, and point-of-care applicability of pulse wave analysis position it as a promising screening tool rather than a replacement for definitive CT-based assessment.

This distinction is particularly relevant in nephrology practice, where serial monitoring of cardiovascular risk is necessary but frequent CT imaging is impractical due to cost, radiation exposure, and accessibility limitations. Pulse wave technology could potentially fill this gap by identifying which CKD patients warrant definitive CT-based CAC assessment, thereby optimizing resource utilization while maintaining vigilant cardiovascular risk surveillance.

Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

The validated association between CAC progression and adverse clinical outcomes in CKD populations [2] [3] underscores the critical importance of effective detection strategies. Pulse wave-driven machine learning approaches offer a promising adjunct to existing methodologies, particularly for serial monitoring and initial risk stratification in resource-limited settings.

Several research priorities emerge to advance this field. First, validation in larger, multi-center CKD cohorts spanning earlier disease stages (CKD 3-4) is essential to establish generalizability beyond ESRD populations. Second, technical refinement of feature extraction algorithms and exploration of alternative machine learning architectures may enhance diagnostic accuracy. Third, longitudinal studies evaluating the ability of pulse wave-based CAC monitoring to guide therapy and improve clinical outcomes would represent the ultimate validation of this approach.

For drug development professionals, the emergence of reliable, non-invasive CAC monitoring tools creates opportunities for efficient endpoint assessment in clinical trials targeting cardiovascular risk reduction in CKD populations. The ability to serially evaluate CAC progression without repeated CT imaging could significantly reduce trial costs and participant burden while maintaining objective assessment of therapeutic efficacy.

In conclusion, while CT-based CAC assessment remains the gold standard for cardiovascular risk stratification in renal patients, pulse wave-driven machine learning represents a promising complementary technology with distinct advantages for screening and serial monitoring. Further validation and refinement of this approach may substantially enhance cardiovascular risk management in the vulnerable CKD population.

The arterial system is not merely a passive conduit for blood flow but a dynamic interface where hemodynamic forces interact with vascular biology. Arterial stiffness represents a key manifestation of vascular aging and pathology, fundamentally altering how pressure waves travel through the arterial tree. These alterations produce characteristic changes in pulse waveform morphology that can be quantified and analyzed. The relationship between arterial properties and pulse contours forms the foundation for non-invasive cardiovascular assessment, particularly as technological advances enable increasingly sophisticated analysis techniques.

Central to this relationship is the phenomenon of wave reflection, wherein pressure waves encounter impedance mismatches at branching points and vascular beds, generating reflected waves that travel backward toward the heart. In compliant, healthy arteries, these reflected waves arrive during diastole, potentially enhancing coronary perfusion. With increased arterial stiffness, wave velocity rises, causing reflected waves to arrive earlier during systole, augmenting central systolic pressure and increasing cardiac afterload. This dynamic interplay between forward and reflected waves creates distinct morphological features in the arterial pulse contour that carry diagnostic information about vascular health [10].

Technical Comparison of Arterial Assessment Methodologies

Functional versus Morphological Assessment Approaches

Vascular assessment methodologies generally fall into two categories: functional measures of arterial dynamics and morphological measures of arterial structure. Each approach offers distinct advantages and captures different aspects of vascular pathology, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Vascular Assessment Methodologies

| Assessment Type | Specific Measures | Physiological Correlate | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional | Carotid-femoral PWV (cfPWV) | Aortic stiffness | Gold standard, strong prognostic value | Requires multi-site measurement |

| Brachial-ankle PWV (baPWV) | Global arterial stiffness | Simple, non-invasive | Includes muscular arteries | |

| Augmentation Index (AIx) | Wave reflection magnitude | Independent prognostic value | Heart rate dependent | |

| Pulse Wave Upstroke Time (UT) | Ventricular ejection characteristic | CAC association [11] | Limited standalone value | |

| Morphological | Carotid Intima-Media Thickness (cIMT) | Early structural adaptation | Well-validated, predictive | Measurement variability |

| Coronary Artery Calcium (CAC) | Advanced atherosclerosis | Direct coronary assessment | Radiation exposure, cost |

Hemodynamic Parameter Performance Characteristics

Different hemodynamic parameters demonstrate varying strengths in their associations with coronary artery calcification across patient populations. Table 2 summarizes key performance characteristics from clinical studies.

Table 2: Hemodynamic Parameters and Coronary Artery Calcification Associations

| Parameter | Population | CAC Association | Statistical Strength | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cfPWV | Framingham Offspring (n=1,015) | Positive with TAC, AAC, CAC | OR 1.48 per SD for CAC [12] | Multivariable adjusted |

| Framingham Gen 3 (n=1,905) | Stronger in younger cohort | OR 2.69 per SD for TAC [12] | Age effect modification | |

| baPWV | Prospective cohort (n=1,124) | CAC progression predictor | OR 2.14 (Q4 vs Q1) [13] | 2.7-year follow-up |

| Pulse Wave UT | Clinical (n=133) | Independent CAC correlate | P=0.038 [11] | Multivariate analysis |

Experimental Protocols in Pulse Wave Analysis

Standardized Pulse Wave Acquisition Protocol

The methodology for pulse wave acquisition follows rigorous standardization to ensure reproducible measurements:

Patient Preparation: Participants refrain from alcohol, caffeine, and hot drinks for 12 hours prior to measurement. They rest in a supine position for at least 5 minutes in a temperature-controlled room (20-24°C) before measurement begins [10].

Equipment Setup: Blood pressure cuffs are appropriately sized and positioned on the right upper arm (brachial artery) and right lower leg (anterior tibial artery). For carotid-femoral PWV measurement, distance measurements are taken between the suprasternal notch and femoral artery using a tape measure [10].

Signal Acquisition: Multiple pulse wave recordings (typically 10-20 consecutive beats) are obtained at each measurement site. Measurements with motion artifacts or poor signal quality are immediately repeated. The entire protocol typically takes 15-20 minutes per subject [10].

Signal Processing: Acquired waveforms are processed using automated algorithms that identify fiducial points (systolic upstroke, peak systolic, diastole). The quality index threshold is typically set to >80% for acceptable recordings [6].

Pulse Wave Feature Extraction Methodology

The morphological analysis of pulse waves focuses on specific characteristic points and derived parameters:

Primary Feature Identification: The analysis identifies the systolic main wave (P1), tidal wave (P2), and dicrotic wave (P3) on the pulse contour. With increasing arterial stiffness and CAC severity, the tidal wave becomes progressively attenuated and less distinguishable from the main wave [6].

Time-Domain Parameters: These include pulse transit time (time between systolic foot and diastolic notch), upstroke time (time from diastolic minimum to systolic maximum), and ejection duration (systolic phase) [11] [6].

Amplitude Ratios: The augmentation index is calculated as the difference between the second and first systolic peaks divided by pulse pressure, expressed as a percentage. Reflection magnitude is derived from harmonic analysis of forward and backward waves [10].

Complexity Features: Non-linear analysis includes multiscale entropy and complexity indices that quantify the irregularity of pulse waveforms, with higher CAC burden associated with reduced complexity [6].

Machine Learning Model Development Protocol

The application of machine learning to pulse wave analysis follows a structured pipeline:

Feature Engineering: Initial pulse wave features undergo selection based on univariate associations with CAC scores. Highly correlated features (r > 0.8) are removed to minimize multicollinearity. Feature importance is ranked using random forest or XGBoost intrinsic metrics [8] [6].

Model Architecture: Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) models are implemented with nested cross-validation to optimize hyperparameters. The typical architecture includes 100-500 estimators, maximum depth of 3-6, and learning rate of 0.01-0.1 [6].

Validation Framework: Models are evaluated using fivefold cross-validation with strict separation of training and validation sets. Performance metrics include area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC), accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score [8] [6].

Clinical Implementation: Successful models are tested on independent validation cohorts with different demographic characteristics to assess generalizability. The output typically provides both binary classification (high CAC vs. low CAC) and continuous risk prediction [8].

Research Reagents and Experimental Toolkit

Essential Research Materials and Instruments

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Pulse Wave Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Instrument | Research Function | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Wave Acquisition | SphygmoCor System (AtCor Medical) | Applanation tonometry for central hemodynamics | Central pressure waveforms, augmentation index |

| Vascular Explorer (Enverdis) | Oscillometric PWV measurement | Multi-site PWV (aortic, carotid-femoral, brachial-ankle) | |

| VP-1000 System (OMRON) | Automated baPWV measurement | Simultaneous brachial and tibial waveform capture | |

| Computational Analysis | Dr. Wise AI-Assisted Diagnosis System | Automated pulse wave feature extraction | Volumetric analysis, threshold-based segmentation |

| Scikit-learn Python Library | Machine learning implementation | GBDT, random forest, SVM algorithms | |

| Validation Reference | Multi-detector CT (MDCT) | CAC quantification gold standard | Agatston scoring protocol, ECG-gated acquisition |

Performance Comparison of Pulse Wave Analysis Techniques

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Methodologies

Different pulse wave analysis approaches demonstrate varying capabilities for detecting coronary artery calcification, with machine learning-enhanced methods showing particular promise.

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Pulse Wave Analysis Methods for CAC Detection

| Methodology | Study Population | Accuracy Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWV-based Classification | Community cohort (n=2,920) [12] | OR 1.48-2.69 per SD for CAC | Strong prognostic value | Requires multiple measurement sites |

| Pulse Wave ML (GBDT) | ESRD patients (n=58) [6] | 84.1% accuracy, 0.962 AUC | Superior in younger patients [8] | Single-center validation |

| Pulse Wave ML (Multiple Algorithms) | CKD patients (n=124) [8] | >80% balanced accuracy | Non-invasive, cost-effective | Limited to high-risk population |

| baPWV Quartile Analysis | Health screening (n=1,124) [13] | OR 2.14 for CAC progression | Simple measurement | Moderate accuracy alone |

Age-Stratified Performance

The performance of pulse wave analysis techniques varies significantly across age groups, with machine learning approaches demonstrating particular utility in younger populations. In patients under 50 years old, pulse wave-based classifiers show superior sensitivity compared to traditional risk factor-based models [8]. This enhanced performance in younger cohorts suggests that functional arterial assessment may detect early vascular changes before advanced calcification develops.

The relationship between arterial stiffness and CAC also demonstrates age-dependent patterns, with stronger associations observed in younger individuals from the Framingham Third Generation Cohort compared to the older Offspring Cohort [12]. This effect modification by age underscores the importance of considering life-course vascular changes when interpreting pulse wave parameters.

The systematic analysis of pulse morphology provides a non-invasive window into coronary artery health, with particular value for early risk stratification. Machine learning-enhanced pulse wave analysis demonstrates performance characteristics that suggest potential clinical utility, especially in younger populations and high-risk groups where traditional risk factors may lack sensitivity. The integration of functional arterial assessment with morphological evaluation creates a comprehensive vascular profiling approach that may enhance personalized cardiovascular risk prediction and monitor response to therapeutic interventions across the cardiovascular disease spectrum.

Coronary Artery Calcification (CAC) is a well-established marker of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk. The emergence of pulse wave analysis, enhanced by machine learning, presents a promising frontier for the non-invasive assessment of CAC severity. This guide objectively compares the performance of this novel approach against traditional imaging, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of validating pulse wave-driven machine learning for CAC detection. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these morphological patterns and the experimental data supporting them is crucial for advancing diagnostic technologies and therapeutic interventions. Recent studies demonstrate that specific, quantifiable changes in pulse wave morphology are directly associated with increasing CAC severity, enabling machine learning models to achieve classification accuracy exceeding 80% [6] [7] [14].

Comparative Performance of Pulse Wave Analysis vs. Traditional CAC Assessment

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of pulse wave-driven machine learning models in detecting CAC severity, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pulse Wave-Based ML Models for CAC Assessment

| Study and Patient Population | Key Pulse Wave Features Utilized | Machine Learning Model | Classification Task | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD patients on hemodialysis (N=58) [6] [7] [14] | Waveform morphology (NA, NB, NC, PB, PC), descending limb parameters, complexity/distribution features. | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | 4-class severity (No, Mild, Moderate, Severe CAC) | Accuracy: 84.1% (cross-val), Macro-AUC: 0.962; excelled in identifying Severe cases. |

| CKD stage 5 patients (N=124) [8] [15] | Morphological pulse wave features from radial and brachial arteries. | Not Specified (Pulse wave-based classifier) | Binary (High CAC ≥100 Agatston units) | Balanced Accuracy: >80%; superior sensitivity in patients <60 years old. |

| Multi-center study (N=348) [16] | Harmonic differences (e.g., |ΔC10|, |ΔD9|, ΔP1CV) between left and right hands. | Logistic Regression | Binary (SYNTAX score ≥22) | AUC: 0.89 (Males), AUC: 0.92 (Females) |

The data indicates that pulse wave analysis is particularly effective in stratified risk assessment. The model tested on ESRD patients demonstrated robust performance across four distinct levels of CAC severity [6] [14], while the approach also showed high balanced accuracy for binary classification of high-risk CAC in a CKD population [8]. A key advantage is its enhanced sensitivity in younger patient cohorts, where traditional risk factors may be less indicative [8] [15].

Characteristic Pulse Wave Morphological Patterns

The association between pulse wave morphology and CAC severity is not random; it follows a distinct, observable pattern. The quantifiable features underlying these morphological changes are detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Characteristic Pulse Wave Morphological Changes Associated with Increasing CAC Severity

| Morphological Feature | Description of Change with Increasing CAC Severity | Physiological Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Tidal/Dicrotic Wave | Becomes progressively attenuated and less distinguishable from the main wave [6] [14]. | Increased arterial stiffness and altered wave reflections due to vascular calcification [6]. |

| Overall Waveform Contour | Evolves into a smoother morphology with a less defined diastolic phase [6] [14]. | Reduced vascular compliance and damping of secondary waves. |

| Specific Parameter: NB | Significantly increases in Mild/Moderate groups vs. No Calcification group [14]. | Directly associated with the hemodynamic impact of calcification. |

| Specific Parameter: PB | In Severe Calcification group, becomes significantly higher than in Mild/Moderate groups during HD [14]. | Indicates a shift in the timing and magnitude of reflected waves. |

| Left-Right Harmonic Differences | Harmonic indices (e.g., amplitude, energy, phase) show greater asymmetry between hands [16]. | Suggests that localized coronary lesions create detectable, asymmetrical effects on systemic circulation. |

The progression of these patterns is systematic. In individuals without significant CAC, the pulse waveform displays a well-defined main wave followed by clear tidal and dicrotic waves [6]. As CAC burden increases, these secondary waves begin to merge closer to the main wave and diminish in amplitude, leading to a smoother, more monolithic waveform contour, which is especially pronounced in cases of severe calcification [6] [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Patient Recruitment and Data Acquisition

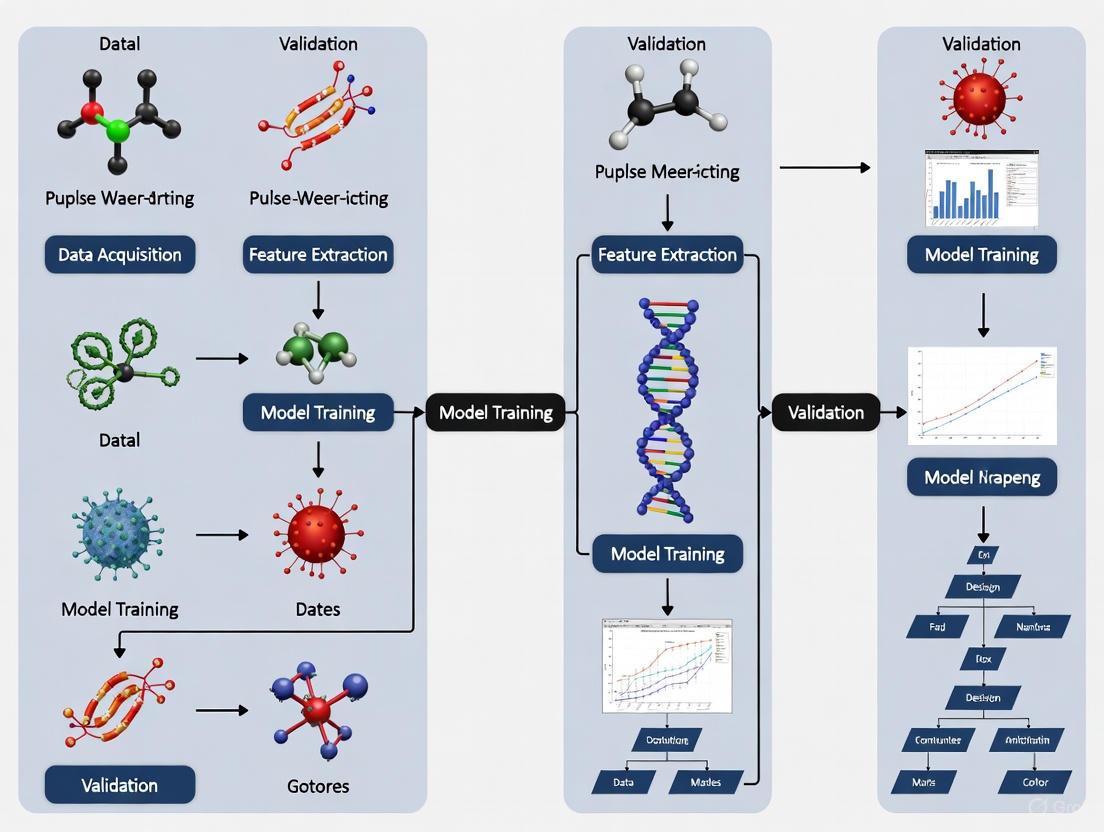

The following workflow diagram outlines the standard experimental protocol for pulse wave-based CAC assessment.

Key Steps in the Experimental Workflow:

Cohort Selection: Studies typically focus on high-risk populations, such as patients with End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis [6] [14] or those with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) [8] [15]. Participants are enrolled with informed consent under Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved protocols.

Ground Truth Assessment: The severity of CAC is definitively classified using computed tomography (CT) scans. The Agatston score is the clinical gold standard, with studies often using a four-tier classification: No calcification (0), Mild (1-100), Moderate (101-400), and Severe (>400 Agatston units) [6] [17] [14].

Pulse Wave Recording: Pulse wave signals are non-invasively recorded using devices like the SphygmoCor system (AtCor Medical) [8] [15] or similar hardware. Signals are typically captured from the radial or brachial artery at a high sampling rate. In studies involving hemodialysis patients, recordings may be taken at multiple time points before, during, and after dialysis to track dynamic changes [6] [14].

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction: The raw pulse wave signals are pre-processed (e.g., filtered, normalized). Subsequently, a wide array of features is extracted. These can be broadly categorized into:

- Morphological Parameters: Quantifying the amplitude and timing of the main wave, tidal wave, and dicrotic wave (e.g., NA, NB, PC) [14].

- Complexity and Distribution Features: Reflecting the signal's entropy and statistical properties.

- Harmonic Features: Obtained via Fourier transform to decompose the waveform into its constituent frequencies [16].

- Left-Right Difference Metrics: Calculating the absolute difference in harmonic indices between the two hands [16].

Machine Learning Model Development

The processed data is then used to train predictive models.

Model Selection: Commonly used algorithms include Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) [6] [14] and Logistic Regression [16]. GBDT is often favored for its ability to model complex, non-linear relationships between multiple features.

Training and Validation: The dataset is split into training and testing sets. Model performance is rigorously evaluated using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., fivefold) to ensure generalizability and to avoid overfitting. Final model performance is reported on a held-out independent test set [6] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Pulse Wave CAC Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Wave Acquisition System | Non-invasively captures high-fidelity arterial waveform signals. | SphygmoCor system (AtCor Medical) [8] [15]. |

| LDCT/CT Scanner | Provides the ground truth Agatston score for CAC severity classification. | Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) [6]. |

| Signal Processing Software | For pre-processing, feature extraction, and harmonic analysis of pulse waves. | Custom scripts in Python/MATLAB for Fourier analysis [16]. |

| Machine Learning Framework | Provides environment for developing and training predictive models (GBDT, etc.). | Common frameworks like Scikit-learn, XGBoost, or TensorFlow. |

| Harmonic Analysis Algorithm | Decomposes pulse wave into harmonics to quantify energy and phase differences. | Fourier transform for 0th to 11th harmonics [16]. |

The evidence confirms that specific morphological patterns in pulse waves are systematically associated with the severity of Coronary Artery Calcification. The progressive attenuation of tidal waves and smoothing of the overall waveform contour provide a physically interpretable signature of increasing arterial stiffness and calcific burden. When these morphological features are leveraged by machine learning models—primarily Gradient Boosting Decision Trees—the resulting tools demonstrate high diagnostic performance, with accuracy exceeding 80% and AUC values above 0.96 in multi-class severity assessment. This methodology validates the thesis that pulse wave-driven machine learning is a robust, non-invasive, and cost-effective strategy for CAC detection and risk stratification, offering a compelling alternative to traditional CT-based screening, especially in high-risk and younger patient populations.

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a well-established marker of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease, with its presence and severity directly correlated with increased risk of major adverse cardiac events. The accurate detection and quantification of CAC is therefore crucial for risk stratification and clinical decision-making. The current clinical gold standard for CAC assessment, the Agatston score, is derived from electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated computed tomography (CT) scans. However, this and other established imaging modalities present significant limitations that hinder their utility for widespread screening and frequent monitoring, creating an urgent need for alternative approaches. This review objectively compares the performance of current gold-standard CAC detection methods against emerging alternatives, with a specific focus on validating pulse wave-driven machine learning as a non-invasive screening tool. By examining the technical constraints, clinical applicability, and performance metrics of each approach, we provide a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to evaluate the next generation of CAC detection technologies.

Limitations of Current Gold-Standard CAC Detection Methods

Current modalities for detecting vascular calcification, while clinically valuable, face persistent limitations that affect their sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Current CAC Detection Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Key Limitations | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECG-Gated CT | >400 µm (clinical systems) [18] | Radiation exposure, high cost, limited access, cannot detect microcalcifications (<50 µm) [6] [18] [19] | Gold standard for Agatston scoring; excellent for macrocalcification detection [19] |

| Non-ECG-Gated CT | >400 µm (clinical systems) [18] | Motion artifacts, overestimation of calcification volume (blooming artefacts), overlap in attenuation between iodine contrast and calcification [18] [20] | Suitable for screening; prognostic value for cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular events [20] |

| Na[18F]F PET | 4-5 mm (clinical systems) [18] | Cannot differentiate between physiological and pathological calcification; low specificity; requires hybrid imaging (CT/MRI) for anatomy [18] | Detects active microcalcification sites; high target-to-background ratio [18] |

| Intravascular Ultrasound (IVUS) | ~100 µm [18] | Invasive procedure; unable to penetrate calcium to measure thickness; detects only macrocalcifications [18] | Near-histology quality images of vascular wall and plaque; used in specialized catheterization procedures [18] |

A critical limitation across all conventional imaging techniques is the inability to reliably detect microcalcifications (calcifications with a diameter below 50 µm), which are a key indicator of plaque instability and increased rupture risk [18]. Although preclinical CT systems can achieve resolutions of up to 1 µm, clinical CT systems, including the novel photon-counting CT, lack the spatial resolution to identify these early, high-risk calcification events [18]. This represents a significant diagnostic gap, as the identification of microcalcifications could allow for interventions at a stage where plaque stability can still be modulated [18].

Furthermore, issues of cost, accessibility, and patient burden are pronounced. ECG-gated CT scans, while precise, are performed less frequently (approximately 0.5 million per year in the U.S.) compared to non-ECG-gated chest CT scans (10.6 million per year), and face greater challenges with insurance coverage [19]. The necessity for iodine-based contrast agents in diagnostic images and the associated radiation exposure further limit the feasibility of CT for routine, repeated screening [18] [19].

Experimental Protocols for Current and Emerging Methods

Protocol for Agatston Scoring via ECG-Gated CT

The traditional Agatston method quantifies CAC through a manual-to-semi-automated process on non-contrast, ECG-gated CT scans [19]. The protocol involves:

- Image Acquisition: A non-contrast CT scan is performed with prospective ECG-gating to capture images during diastole, minimizing cardiac motion artifacts.

- Voxel Identification: Software automatically identifies voxels within the coronary arteries with an attenuation greater than 130 Hounsfield Units (HU), a threshold set to distinguish calcium from surrounding tissues.

- Area and Weighting Calculation: The area of all qualifying voxels is calculated. Each calcified area is then multiplied by a density weighting factor (1-4) based on its peak HU value.

- Score Calculation: The Agatston score is the sum of these weighted calcium scores across all coronary arteries. Patients are stratified into risk categories: 0 (very low), 1-99 (mild), 100-299 (moderate), 300-399 (moderate to severe), and ≥400 (severe) [6] [19].

Protocol for AI-Driven CAC Scoring on Non-ECG-Gated CT

Artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, is being applied to overcome the limitations of ECG-gated scans by leveraging the more abundant non-ECG-gated chest CTs [19]. A typical protocol involves:

- Data Curation: A large dataset of non-ECG-gated chest CT scans is assembled, often retrospectively.

- Model Training: A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a type of deep learning model, is trained on this dataset. The model is taught to identify and quantify coronary calcium deposits.

- Validation: The AI-generated CAC scores are validated against the reference standard of ECG-gated CT Agatston scores.

- Outcome Correlation: The model's performance is further assessed by correlating its scores with clinical outcomes, such as major adverse cardiac events. Studies have shown that AI-generated scores from non-gated CTs maintain strong agreement with manual methods and support effective risk stratification [19].

Protocol for Pulse Wave-Driven Machine Learning Assessment of CAC

Emerging as a radically non-invasive and cost-effective alternative, pulse wave analysis uses machine learning to infer CAC severity from arterial waveform characteristics [6] [8]. A representative study protocol is as follows:

- Patient Enrollment & Reference Standard: A cohort (e.g., 58 patients with end-stage renal disease) is enrolled. CAC severity is definitively classified using low-dose CT (LDCT) into categories (e.g., 0, 1-100, 101-400, >400 Agatston units) [6].

- Pulse Wave Acquisition: Radial artery pulse waveforms are recorded non-invasively over a period, for instance, before, during, and after hemodialysis, using a device like the SphygmoCor system [6] [8].

- Feature Extraction: Key morphological features are extracted from the pulse waveforms. These include parameters related to the waveform's morphology (e.g., attenuation of tidal waves), descending limb, complexity, and distribution [6]. With increasing CAC severity, the tidal waves become progressively attenuated, resulting in a smoother overall waveform [6].

- Model Training and Validation: A Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) model is trained using the extracted pulse wave features to classify CAC severity. The model's performance is evaluated using fivefold cross-validation and an independent test set [6]. One study achieved an average accuracy of 84.1% and a macro-AUC of 0.962, demonstrating robust performance, particularly in identifying severe calcification cases [6]. Another study focusing on high CAC (≥100) reported a balanced accuracy exceeding 80% [8].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of this experimental protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Pulse Wave-Driven CAC Detection Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SphygmoCor System | Non-invasive acquisition of radial artery pulse waveforms [8]. | A commercial device for applanation tonometry and pulse wave analysis. |

| Low-Dose CT (LDCT) | Provides the reference standard Agatston score for model training and validation [6]. | Used to classify patients into CAC severity groups. |

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | A machine learning algorithm that builds an ensemble of decision trees for classification tasks [6]. | Used to correlate pulse wave features with CAC severity. |

| Pulse Wave Features | Quantitative parameters extracted from the waveform signal used as model input [6]. | Includes morphology, descending limb, complexity, and distribution parameters. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A class of deep learning neural networks used for automated analysis of medical images [19]. | Applied for direct CAC scoring on non-ECG-gated CT scans. |

The current gold-standard methods for CAC detection, while foundational to cardiovascular risk assessment, are constrained by significant limitations in detecting early-stage microcalcifications, issues of cost, accessibility, and patient safety. The validation of emerging technologies, particularly pulse wave-driven machine learning, demonstrates a promising paradigm shift. The experimental data confirms that this non-invasive approach can classify CAC severity with high accuracy (exceeding 80% balanced accuracy and AUC of 0.962), offering a viable, cost-effective, and repeatable screening tool. For researchers and drug development professionals, this technology not only presents a new avenue for early patient identification and risk stratification but also opens the possibility of frequent monitoring of CAC progression or regression in response to therapeutic interventions, a capability that was previously impractical with traditional imaging modalities.

Building a Predictive Model: From Signal Acquisition to Machine Learning Algorithm

The accurate acquisition and preprocessing of radial artery waveforms represent a critical foundation for advancing cardiovascular diagnostic research, particularly in the validation of non-invasive biomarkers for coronary artery calcification (CAC). Coronary artery calcification, a well-established marker of atherosclerotic burden and a powerful predictor of cardiovascular events, has traditionally been assessed using computed tomography (CT) [4] [21]. However, CT screening is costly, resource-intensive, and impractical for large-scale population use, motivating the search for alternative, more accessible modalities [22]. The radial artery pulse waveform contains rich physiological information regarding vascular stiffness, cardiac function, and hemodynamic properties that may correlate with coronary artery health [23] [24]. This guide systematically compares the performance, technical specifications, and implementation requirements of contemporary radial artery signal acquisition technologies, providing researchers with objective data to inform their experimental designs for pulse wave-driven machine learning applications.

Comparative Analysis of Acquisition Modalities

The selection of an appropriate sensing modality represents the first critical decision in establishing a radial artery acquisition protocol. Current technologies can be broadly categorized into pressure-based sensor arrays, optical systems, and hybrid approaches, each with distinct operational characteristics and performance trade-offs.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Radial Artery Acquisition Modalities

| Acquisition Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Measurable Parameters | Signal Quality Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS Pressure Sensor Array [23] | 0.65 mm pitch, 18 sensors spanning 11.6 mm | Not explicitly stated | 3D pulse envelope, pulse width, dynamic pulse width, pulse wave velocity (PWV) | High linearity (±0.1% FS), low hysteresis (0.15% FS), validated against Doppler ultrasound |

| Fabry-Perot Interferometry [25] | Sub-micrometer displacement sensitivity | Limited by sensor bandwidth and interpolation methods | Arterial pulse waveform (APW), phase dynamics, rate of change | Robust to artifacts, provides complete morphological waveform |

| Multimodal FCG-PPG Sensor [26] | Single measurement site | Simultaneous mechanical-optical acquisition | PW morphology, derivatives, time delay between mechanical and optical signals | Normalized cross-correlation >0.98 between modalities |

| Piezoelectric Tonometry [26] | Single point measurement | Suitable for wearable monitoring | PW morphology, pulse transit time (PTT) | Does not require artery applanation |

Table 2: Technical Implementation Requirements and Limitations

| Modality | Skin Contact Requirement | Calibration Complexity | Subject Discomfort | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS Pressure Sensor Array [23] | Direct contact, finger-worn by practitioner | Requires specialized calibration | Minimal when worn by practitioner | complex fabrication, system integration |

| Fabry-Perot Interferometry [25] | Applanation tonometry required | Python-based processing pipeline | Moderate due to applanation | Signal ambiguity at turning points, exceeds λ/4 amplitude |

| Multimodal FCG-PPG Sensor [26] | Direct contact at fingertip | Requires synchronization of dual sensors | Minimal, wearable design | Unexplained delay between optical/mechanical signals |

| Piezoelectric Tonometry [26] | Direct contact, no applanation | Frequent recalibrations needed | Low, suitable for long-term monitoring | Less stable than pressure sensors for quantitative measurements |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

MEMS Pressure Sensor Array Fabrication and Deployment

The ultra-dense MEMS pressure sensor array protocol employs 18 miniature silicon piezoresistive pressure sensors (0.4 mm × 0.4 mm each) packaged on a flexible printed circuit board with a 0.65 mm pitch, creating an effective sensing span of 11.6 mm—3–5 times the diameter of the typical radial artery [23].

Implementation Workflow:

- Sensor Fabrication: Fabricate sensors using a microhole inter-etch and sealing (MIS) process creating beam-island-reinforced structures for high sensitivity (108 mV/3.3 V) and linearity

- Array Assembly: Attach sensors to FPC substrate with precise positional alignment and connect via wire bonding

- Environmental Protection: Coat bonding wires with stiff epoxy resin for reliability while removing material between sensors to maintain flexibility

- Signal Acquisition: Position array over radial artery at inch, bar, and cubit points; record simultaneously from all 18 channels while applying three pressure levels (superficial, medium, deep)

- Data Processing: Construct 3D pulse envelope images from spatial-temporal data; calculate pulse width and dynamic pulse width through envelope analysis

This protocol enables direct measurement of pulse wave velocity by calculating the pulse transit time between the brachial and radial arteries using the same sensor arrays [23].

Fabry-Perot Interferometric Signal Processing Pipeline

The interferometric approach captures arterial pulsation through precise optical path length changes in a low-finesse Fabry-Perot cavity, requiring specialized processing to reconstruct the arterial pulse waveform [25].

Processing Protocol:

- Signal Acquisition: Obtain interferometric time-domain signals from Fabry-Perot sensor applied with applanation tonometry at radial artery

- Preprocessing: Implement outlier removal followed by Butterworth high-pass filtering to eliminate baseline drift

- Normalization: Apply min-max normalization to standardize signal amplitude across subjects and sessions

- Feature Extraction: Calculate rate of change and its Hilbert transform to identify signal envelope and critical points

- Breakpoint Detection: Employ interactive refinement to identify phase change points, constrained by physiological boundaries (even number of breakpoints per cardiac cycle)

- Waveform Reconstruction: Reconstruct arterial pulse waveform from processed interferometric signal using segmented approach

The complete Python-based processing pipeline is publicly available as open-source code, enhancing reproducibility and community development [25].

Multimodal Finger Pulse Wave Sensing

This protocol enables simultaneous mechanical and optical pulse wave acquisition from the same measurement site, providing complementary data streams for enhanced parameter extraction [26].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sensor Integration: Co-locate piezoelectric Forcecardiography (FCG) and photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors in a single housing unit

- Signal Synchronization: Implement hardware or software synchronization to ensure temporal alignment of FCG and PPG data streams

- Data Acquisition: Record finger pulse waves simultaneously from both modalities under resting conditions

- Signal Processing: Apply inversion to PPG light intensity signal; normalize both signals; calculate first and second derivatives

- Cross-Modal Analysis: Compute normalized cross-correlation between FCG and PPG waveforms and their derivatives

- Parameter Extraction: Identify fiducial points in original and derivative signals for morphological parameter calculation

This approach reveals an consistent but unexplained time delay between mechanical (FCG) and optical (PPG) pulse wave signals, highlighting the complex biomechanics of pulse propagation [26].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Critical Components for Radial Artery Waveform Research

| Component | Specification/Function | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MEMS Pressure Sensors [23] | Ultra-small (0.4 mm × 0.4 mm) piezoresistive sensors with high sensitivity (108 mV/3.3 V) | Beam-island reinforced silicon sensors fabricated via MIS process |

| Flexible Printed Circuit Boards [23] | Flexible substrate for sensor integration while maintaining anatomical conformity | Custom FPC with 0.65 mm pitch for 18-sensor array |

| Fabry-Perot Interferometer [25] | Low-finesse optical cavity for precise displacement measurement via phase modulation | Fiber-optic FPI with elastic membrane for applanation tonometry |

| Multimodal Sensor Housing [26] | Integrated mechanical structure for co-locating FCG and PPG elements | Custom housing with piezoelectric FCG and reflective PPG sensors |

| Signal Processing Libraries [25] | Python-based tools for filtering, normalization, and feature extraction | Public GitHub repository: FPI-Pulse-Waveform-Extraction |

| Validation Instrumentation [23] | Reference standard for protocol validation | Color Doppler ultrasound for dynamic pulse width measurement |

The methodological comparison presented in this guide demonstrates significant trade-offs between spatial resolution, implementation complexity, and quantitative accuracy across radial artery acquisition modalities. For machine learning applications targeting coronary artery calcification detection, the MEMS pressure sensor array provides superior spatial characterization of pulse propagation phenomena, which may encode information about coronary vascular health [23]. The Fabry-Perot interferometric approach offers high precision for waveform morphology analysis, while multimodal sensing captures complementary physiological relationships [25] [26]. Researchers should select acquisition protocols based on specific feature requirements for their predictive models, considering that pulse wave velocity and specific morphological features have demonstrated associations with vascular stiffness and coronary artery disease progression [27] [24]. As pulse wave-driven machine learning advances, standardized acquisition and preprocessing protocols will be essential for developing robust, generalizable models for non-invasive coronary artery calcification assessment.

Within the rapidly evolving field of cardiovascular informatics, the validation of pulse wave-driven machine learning (ML) for detecting coronary artery calcification (CAC) represents a critical research frontier. CAC, the deposition of calcium in coronary artery walls, is a definitive marker of atherosclerosis and a powerful predictor of cardiovascular events. The current diagnostic gold standard, computed tomography (CT) for CAC scoring, involves radiation exposure and significant cost, limiting its suitability for widespread screening [6] [28]. Consequently, non-invasive, cost-effective alternatives are urgently needed.

Pulse wave analysis has emerged as a promising non-invasive methodology for cardiovascular assessment. The central thesis of this approach posits that the morphological, temporal, and complexity parameters embedded within pulse wave signals contain rich information about arterial stiffness, endothelial function, and the hemodynamic alterations caused by vascular calcification [6] [29] [28]. The validation of pulse wave-driven ML models hinges on the rigorous engineering of these features to create robust, generalizable tools for CAC detection. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the feature categories and experimental protocols that underpin this innovative research domain.

Comparative Analysis of Pulse Wave Feature Categories

The utility of pulse wave signals for machine learning depends on the extraction of informative features. These parameters can be broadly categorized into morphological, temporal, and complexity-based features, each offering distinct insights into cardiovascular physiology.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Pulse Wave Feature Categories for CAC Detection

| Feature Category | Description | Key Parameters | Physiological Correlation | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological Features | Describe the shape and amplitude characteristics of the pulse waveform [6] [30]. | Main wave amplitude, tidal wave, dicrotic wave, pulse area, Smoothness, number of local extrema (#Extrema) [6] [30]. | Vascular elasticity, peripheral resistance, left ventricular function, wave reflections [6]. | Directly reflects structural and functional vascular status; features are often intuitively understandable. |

| Temporal Features | Pertain to time intervals within the cardiac cycle or between pulse waves. | Pulse Transit Time (PTT), Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV), Upstroke Time (UT), heart rate [29] [28] [31]. | Arterial stiffness; faster PWV indicates stiffer arteries [28]. | Strong, established correlation with arterial stiffness; relatively straightforward to measure. |

| Complexity Features | Quantify the irregularity, variability, or "jaggedness" of the signal over time [29] [30]. | Entropy, Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD), Root Mean Square (RMS), Autocorrelation Function (ACF) [29] [30]. | Overall state of the cardiovascular regulatory system; reduced complexity may indicate pathology. | Captures non-linear dynamics not apparent from shape or timing alone; can improve model stability in ambulatory settings [29]. |

Insights from Comparative Performance

Morphological features demonstrate high clinical relevance, as specific waveform alterations are directly observable with increasing CAC severity. For instance, the tidal wave becomes progressively attenuated and less distinguishable in severe calcification, resulting in a smoother overall waveform [6]. Concurrently, parameters like Smoothness increase and #Extrema decrease, indicating a loss of waveform complexity [30].

Temporal features, particularly PWV, provide a well-validated measure of arterial stiffness, which has a pathophysiological link to atherosclerosis. A study of 986 Japanese men established a clear association, with the prevalence of CAC rising from 20.6% in the lowest baPWV quartile to 66.7% in the highest [32]. The optimal baPWV cutoff for detecting CAC was identified as 1612 cm/s [32].

Complexity features add a crucial dimension to the feature set. Research indicates that parameters like HFD and ACF maintain significant contributions to blood pressure estimation even during high cardiac output fluctuations, whereas morphological features may become less reliable under such unstable hemodynamic conditions [29]. This suggests that complexity features can enhance model robustness.

Experimental Protocols for Feature-Driven ML Model Validation

The validation of ML models for CAC detection requires meticulously designed experiments. The following protocols detail the methodologies from key studies in the field.

Protocol 1: Radial Artery Pulse Wave Analysis for CAC Severity Stratification

This protocol is designed to extract features from radial artery waveforms to classify CAC severity in high-risk patients [6].

- Objective: To evaluate the utility of radial artery pulse waveform features for the non-invasive assessment of CAC severity in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis.

- Patient Cohort: 58 patients with ESRD. CAC severity was assessed via low-dose CT and classified into four groups using Agatston scores: no calcification (0), mild (1–100), moderate (101–400), and severe (>400) [6].

- Signal Acquisition: Radial artery pulse waveforms were recorded non-invasively before, hourly during, and after a hemodialysis session.

- Feature Extraction: A comprehensive set of features was extracted based on observed morphological differences among the CAC groups. This included parameters related to:

- Waveform morphology (e.g., main wave, tidal wave)

- Descending limb characteristics

- Signal complexity and distribution

- Mean values

- Full-process stereoscopic pulse wave features [6]

- Model Training and Validation: A Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) model was trained using the extracted waveform features. Model performance was evaluated using fivefold cross-validation and an independent test set [6].

Protocol 2: Photoplethysmography (PPG) Complexity Analysis for Hemodynamic Assessment

This protocol uses model-based simulation to interpret the temporal complexity of PPG signals and its relationship to blood pressure, a key hemodynamic parameter [29].

- Objective: To interpret stochastic PPG patterns via simulation and optimize BP estimation algorithms by understanding the physiological implications of temporal complexity.

- Simulation Framework: A modified four-element Windkessel (WK4) model was used, incorporating blood pressure-dependent compliance profiles. This model simulates PPG responses to pulse and continuous stimuli at various timescales [29].

- Complexity Quantification: The temporal complexity of the simulated and real PPG signals was quantified using:

- Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD): Measures the fractal dimension of a time series signal.

- Autocorrelation Function (ACF): Assesses the correlation of a signal with a delayed copy of itself over time [29].

- Experimental Validation: Continuous recordings of BP, PPG, and stroke volume from 40 healthy subjects were used to validate the simulation results. The contribution of HFD and ACF to BP estimation was calculated and compared against traditional morphological features [29].

Protocol 3: Pulse Wave-Based Screening for High CAC in CKD Patients

This protocol compares the effectiveness of pulse wave features against traditional risk factors for identifying high CAC scores [8] [15].

- Objective: To investigate a pulse wave analysis and ML approach for identifying CKD patients at high risk for coronary atherosclerosis (CAC ≥ 100 Agatston units) [8] [15].

- Study Population: Retrospective data from 124 patients with CKD stage 5 who underwent kidney transplantation.

- Data Collection:

- Model Development: Two ML models were developed and compared:

- Performance Analysis: Model performance was assessed based on balanced accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity, with particular attention to performance across different age groups [8] [15].

Performance Benchmarking of Feature-Based ML Models

Quantitative results from implemented studies demonstrate the efficacy of feature-engineered ML models for CAC detection and related cardiovascular assessment.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Pulse Wave Feature-Based Machine Learning Models

| Study Focus | Model Type | Key Features Used | Performance Metrics | Comparative Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAC Severity Stratification in ESRD [6] | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | Morphological, descending limb, complexity, and distribution features from radial pulse waves. | Avg. Accuracy: 84.1%Macro-AUC: 0.962 (5-fold CV)Test Set Accuracy: 83.9%Test Set AUC: 0.961 | Model performed particularly well in identifying "Severe Calcification" cases. |

| High CAC Screening in CKD [8] [15] | Pulse Wave-Based Classifier | Engineered features from SphygmoCor pulse wave signals. | Balanced Accuracy: >80%Superior sensitivity in patients <60 years old. | Outperformed a model based on Traditional Risk Factors (TRF), especially in younger patients. |

| AI in CT Angiography [33] | AI (Deep Learning) | Direct image features from CTA. | For Calcified Plaque Detection:Sensitivity: 0.93Specificity: 0.94AUC: 0.98 | Demonstrates the high performance of direct imaging but highlights the trade-off with cost/accessibility vs. non-invasive pulse wave. |

| PWV for CAC Detection [32] | Statistical Model | Brachial-ankle PWV (baPWV). | CAC Prevalence vs. baPWV Quartile: 20.6% to 66.7%.Optimal baPWV Cutoff: 1612 cm/s. | Provides a simple, validated threshold for a single temporal feature, useful for baseline screening. |

Signaling Pathways, Workflows, and Logical Frameworks

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows in pulse wave-driven feature engineering for CAC detection.

Pulse Wave to CAC Detection Logic

Feature Engineering and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the described experimental protocols requires specific tools and technologies. This table details key solutions used in the featured research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Pulse Wave CAC Studies

| Tool / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| SphygmoCor System (AtCor Medical) [8] [15] | Hardware & Software | Non-invasive acquisition and analysis of arterial pulse waves, including central aortic waveforms. | Used for pulse wave signal collection in CKD patient studies for CAC screening [8] [15]. |

| Photoplethysmography (PPG) Sensor [29] [31] | Optical Sensor | Measures volumetric changes in peripheral blood circulation, providing a PPG waveform for analysis. | Fundamental for single-site, non-invasive BP estimation and complexity analysis studies [29] [31]. |

| Biopac PPG Systems [30] | Data Acquisition Hardware | High-fidelity recording of physiological signals, including PPG and ECG, often in research laboratory settings. | Used in controlled studies for recording continuous PPG signals from fingers with synchronized ECG [30]. |

| Four-Element Windkessel (WK4) Model [29] | Physiological Model | A lumped-parameter model of the arterial system used to simulate blood flow and pressure relationships. | Employed in in-silico simulations to generate dynamic PPG signals and interpret their relationship with BP [29]. |

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) [6] | Machine Learning Algorithm | A powerful ensemble learning method that builds sequential decision trees to correct previous errors. | Achieved state-of-the-art performance (AUC >0.96) in classifying CAC severity from radial pulse wave features [6]. |

| Higuchi Fractal Dimension (HFD) [29] | Computational Algorithm | Quantifies the fractal dimension (complexity) of a time-series signal. | A key complexity feature used to quantify PPG temporal patterns and correlate them with hemodynamic states [29]. |

The accurate detection and assessment of coronary artery calcification (CAC) is a critical component of cardiovascular risk stratification. Recent advances in non-invasive methodologies, particularly those leveraging pulse wave analysis and machine learning (ML), have opened new avenues for early and efficient CAC detection. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of various ML algorithms, with a focused examination of Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDT) and their variants, within the context of CAC detection research. We summarize quantitative experimental data, detail methodological protocols from key studies, and provide visualizations of core workflows to assist researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate algorithms for their investigative needs.

Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms

The selection of an optimal machine learning algorithm is paramount for developing robust predictive models in healthcare. The table below summarizes the documented performance of various algorithms across different clinical prediction tasks, including coronary artery disease (CAD) and CAC detection.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms in Cardiovascular Disease Prediction

| Algorithm | Application Context | Reported Performance Metrics | Reference / Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | CAC Severity Classification from Pulse Waves | Accuracy: 84.1%, Macro-AUC: 0.962 (5-fold CV) | [34] [7] |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | CAD Risk Assessment from Clinical Features | AUC: 0.988 (Discovery), 0.953 (Validation) | [35] |

| XGBoost | PCI Success Prediction in CAC Patients | AUC: 0.984, F1-Score: 0.970 | [36] |

| Voting Ensemble | Geochemical Au Concentration Prediction (Methodological Reference) | Lower RMSE and MAPE vs. single models (GB, LR, DT) | [37] |

| Random Forest | General Purpose (Theoretical Framework) | High accuracy, robust to overfitting, handles missing data | [38] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | General Purpose (Theoretical Framework) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, versatile kernels | [35] [38] |

The data indicates that tree-based ensemble methods, particularly boosting algorithms like GBDT and XGBoost, consistently deliver high predictive accuracy in complex medical tasks. The GBDT model demonstrated particular proficiency in classifying CAC severity from pulse wave data, a non-invasive and clinically valuable approach [34]. Furthermore, the superior performance of XGBoost in two independent studies for CAD risk assessment and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) success prediction underscores its robustness and generalizability across different cardiovascular endpoints [35] [36]. Ensemble methods like Voting classifiers have also been shown to outperform their constituent base models, highlighting the value of combining multiple algorithms to enhance predictive power [37].

Detailed Experimental Protocols in CAC Research

Pulse Wave-Driven Machine Learning for CAC Assessment

A pivotal study by Lyu et al. (2025) established a protocol for non-invasive CAC assessment using radial artery pulse waveforms [34] [7].

- Study Population and Data Acquisition: The study enrolled 58 patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing hemodialysis. CAC severity was quantified using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and categorized into four groups based on Agatston scores: no calcification (0), mild (1–100), moderate (101–400), and severe (>400). Radial artery pulse waveforms were recorded from each patient at multiple time points: before, hourly during, and after hemodialysis [34] [7].

- Pulse Wave Feature Extraction: A comprehensive set of features was extracted from the waveform morphology. These included parameters related to the waveform's shape (e.g., main wave, tidal wave), its descending limb characteristics, complexity and distribution metrics, mean value parameters, and "full-process stereoscopic" features capturing changes over the entire dialysis session. The study reported clear morphological differences across CAC groups; for instance, the tidal wave became progressively attenuated and less distinguishable with increasing CAC severity [34].

- Model Training and Evaluation: A Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) model was trained to classify patients into the four CAC severity groups based on the extracted pulse wave features. The model's performance was rigorously evaluated using fivefold cross-validation, yielding an average accuracy of 84.1% and a macro-AUC of 0.962. These results were confirmed on an independent test set (83.9% accuracy, 0.961 macro-AUC), with the model performing exceptionally well in identifying cases of severe calcification [34] [7].

ML for PCI Success Prediction in Calcified Lesions

Another study prospectively developed ML models to predict the success of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (PCI) in patients with moderate to severe CAC [36].

- Data Source and Cohort: The study utilized data from 3271 patients with moderate to severe CAC and 17,998 patients with no/mild calcification who underwent PCI between 2017 and 2018. An external validation cohort consisted of 204 patients from a general hospital [36].

- Feature Set and Model Development: Six machine learning models were developed and validated, including k-nearest neighbor, GBDT, XGBoost, Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and SVM. The models were trained on features derived from coronary angiography, encompassing vascular characteristics and procedural details. The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to handle class imbalance [36].

- Model Performance and Interpretation: The XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance, achieving an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) of 0.984. Model interpretability was facilitated using Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP), which identified the top predictive factors for PCI failure. These included lesion length, minimum lumen diameter, and thrommonary infarction (TIMI) flow grade [36].

Workflow and Algorithm Diagrams

Pulse Wave CAC Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end experimental workflow for assessing coronary artery calcification using pulse wave-driven machine learning, as detailed in the research by Lyu et al. [34] [7].

Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) Architecture

The diagram below outlines the core architecture and learning process of a Gradient Boosting Decision Tree, which forms the basis for algorithms like GBDT and XGBoost used in the cited studies [34] [39] [36].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues essential materials and computational tools referenced in the experimental protocols for pulse wave-driven CAC machine learning research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Pulse Wave CAC Studies

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Cohort with ESRD | Primary study population for model development and validation | High prevalence of CAC provides a robust population for studying severity gradients. [34] [7] |

| Low-Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) | Gold-standard imaging for CAC quantification and labeling. | Used to calculate Agatston scores for ground truth labels. [34] [7] |

| Radial Artery Pulse Wave Recorder | Non-invasive data acquisition of vascular waveform signals. | Device capable of capturing high-fidelity morphological waveforms. [34] |

| Pulse Wave Feature Extraction Software | Computational tool for deriving morphological parameters from raw waveforms. | Extracts key features (e.g., main wave, tidal wave characteristics). [34] |

| Gradient Boosting Framework (e.g., XGBoost, GBDT) | Core machine learning library for model construction. | Offers efficient implementation of boosted tree algorithms. [34] [35] [36] |

| SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) | Post-hoc model interpretability and feature importance analysis. | Critical for understanding model decisions in a clinical context. [35] [36] |

Coronary artery calcification (CAC) represents a significant cardiovascular risk factor, particularly in vulnerable populations such as patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [6]. The accurate detection and stratification of CAC severity is crucial for early intervention and improved patient outcomes. Traditional computed tomography (CT)-based methods, while considered the clinical gold standard, pose issues related to radiation exposure, high costs, and limited accessibility for routine screening [6] [8]. In recent years, pulse wave analysis coupled with machine learning (ML) has emerged as a promising non-invasive alternative for CAC assessment. This review synthesizes recent performance benchmarks—including accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), and cross-validation results—from studies validating pulse wave-driven ML models for coronary artery calcification detection, providing researchers with a comprehensive comparison of this rapidly advancing field.

Performance Benchmarks of Pulse Wave-Driven ML Models for CAC Detection

Recent studies have demonstrated consistently strong performance of machine learning models utilizing pulse wave features for detecting and stratifying coronary artery calcification. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from pivotal studies in this domain.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Pulse Wave-Driven ML Models for CAC Detection

| Study & Population | ML Model | Accuracy (%) | AUC | Cross-Validation | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD patients on hemodialysis (N=58) [6] | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) | 84.1% (avg) | 0.962 (macro) | Fivefold | Robust performance on independent test set (83.9% accuracy, 0.961 AUC) |

| CKD stage 5 patients (N=124) [8] | Pulse wave-based classifier | >80% (balanced) | - | - | Superior to traditional risk factors, especially in patients <50 years |

| General CAD prediction [40] | Random Forest | 92% | - | Holdout validation | Outperformed clinical risk scores (71-73% accuracy) |

| SVM with RBF kernel | - | - | - | Superior to linear/polynomial SVM |

The consistency of high performance across these studies, with AUC values frequently exceeding 0.80 and accuracy above 80%, underscores the substantial potential of pulse wave-driven ML for CAC detection. The gradient boosting model demonstrated particular strength in identifying severe calcification cases [6]. Notably, pulse wave-based classifiers have shown superior balanced accuracy compared to models using traditional risk factors, especially among younger patient populations [8].

Comparative Performance Against Alternative Modalities

When evaluating pulse wave analysis against other non-invasive CAD detection methods, its performance remains competitive while offering advantages in cost, accessibility, and simplicity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison with Alternative Diagnostic Modalities

| Diagnostic Modality | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|