Rapid Prototyping Microfluidic Devices: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Techniques for Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed exploration of 3D printing techniques for the rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices.

Rapid Prototyping Microfluidic Devices: A Comprehensive Guide to 3D Printing Techniques for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a detailed exploration of 3D printing techniques for the rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices. It covers the foundational principles of why 3D printing is revolutionizing microfluidics, delves into specific methodological workflows and biomedical applications, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies for high-fidelity prints, and offers a critical validation framework comparing different printing technologies. The guide synthesizes current best practices to accelerate innovation in lab-on-a-chip development, organ-on-a-chip models, and point-of-care diagnostic tools.

Why 3D Printing is Revolutionizing Microfluidic Device Prototyping

Application Note: Accelerated Prototyping for Microfluidic Device Research

Within the research stream of 3D printing techniques for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, the paradigm shift from traditional fabrication (e.g., soft lithography) to additive manufacturing (AM) represents a critical acceleration in the iterative design-test cycle. This note quantifies the time advantage and details protocols for leveraging this speed in microfluidic device development.

Quantitative Time Comparison: Traditional vs. Additive Manufacturing

The following table summarizes the comparative timelines for producing a single, novel prototype microfluidic device, such as a droplet generator or a concentration gradient generator.

Table 1: Prototyping Timeline Comparison for a Novel Microfluidic Device

| Fabrication Step | Soft Lithography (PDMS) | Additive Manufacturing (DLP/SLA) | Time Advantage (Factor) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Master Mold Creation | Photomask design & ordering: 3-5 business daysSU-8 spin coating, exposure, development: 4-6 hours | CAD Model Design: 1-3 hours (digital file) | ~10-20x |

| 2. Device Replication | PDMS mixing, degassing, curing: 4-6 hoursDemolding, punching, plasma bonding: 1-2 hours | 3D Printer Setup & Print Job: 1-3 hoursPost-processing (washing, curing): 30-60 min | ~3-5x |

| 3. Total Hands-on Time | ~6-9 hours | ~2-4 hours | ~2-3x |

| 4. Total End-to-End Time | 5-7 days | 4-8 hours | ~15-20x |

Data synthesized from current literature and manufacturer technical sheets (2023-2024). The AM process assumes the use of a commercially available high-resolution (e.g., 25-50 µm XY) desktop DLP/SLA printer and biocompatible resins.

Experimental Protocol: Rapid Iteration of Microfluidic Mixer Designs

Objective: To design, fabricate, and functionally test three iterations of a serpentine micromixer within one working day.

Materials & Equipment:

- CAD Software (e.g., Fusion 360, SolidWorks)

- High-Resolution DLP 3D Printer (e.g., Asiga MAX, B9 Core Series)

- Biocompatible, Clear Photopolymer Resin (e.g., Dental SG or Biomedical Clear)

- IPA (≥99%) for washing

- Post-Curing UV Chamber

- Syringe Pumps

- Inlets/Outlets (e.g., Nanoport assemblies or blunt needles)

- Visualization Setup (Microscope with high-speed camera)

- Deionized Water and Colored Dye Solutions

Procedure:

CAD Design (Iteration 1): (60 min) Model a basic two-inlet serpentine mixer channel. Critical dimensions: Channel cross-section 300 x 300 µm, total length 50 mm. Export as

.STL.Slicing & Print Preparation: (15 min) Import

.STLinto printer software. Orient at 45° to build plate to minimize stress and surface artifacts. Generate supports automatically. Slice with a layer thickness of 25-50 µm.Additive Fabrication: (90 min) Load resin, start print. The printer will fabricate the device layer-by-layer via projected UV light.

Post-Processing: (30 min)

- Wash: Transfer printed device to IPA bath. Agitate gently for 3-5 minutes to remove uncured resin.

- Dry: Use compressed air to clear channels.

- Final Cure: Place device in a UV post-curing chamber for 10-15 minutes to achieve final mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

Assembly & Test: (60 min)

- Connect fluidic inlets via bonded ports or press-fit needles.

- Mount device on microscope stage.

- Infuse two colored dyes at equal flow rates (e.g., 10 µL/min each) using syringe pumps.

- Record mixing efficiency at the outlet.

Design Iteration (2 & 3): (Remaining time) Based on observed laminar flow and poor mixing in Iteration 1, modify CAD to incorporate staggered herringbone structures (Iteration 2) or a reduced channel diameter to increase Reynolds number (Iteration 3). Repeat steps 1-5. Two additional design iterations can be completed within the same day.

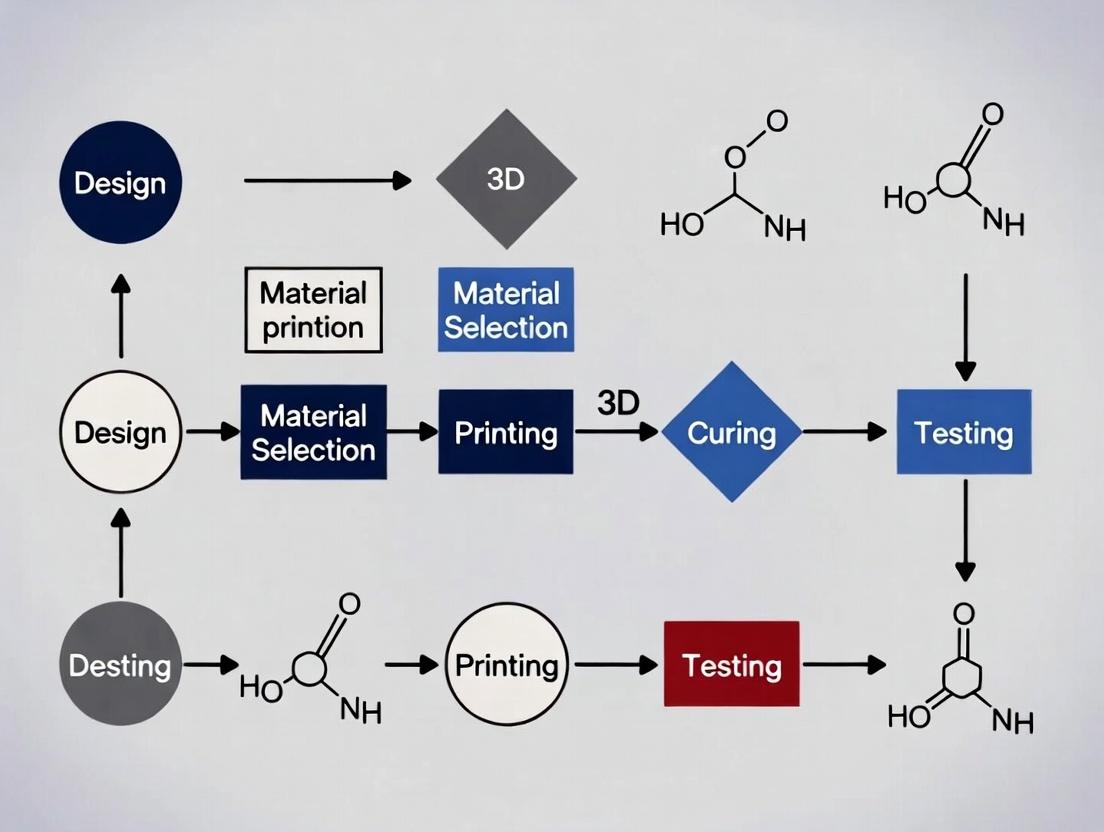

Visualization of the Accelerated Research Workflow

Title: Speed Comparison in Microfluidic Design Iteration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for AM of Microfluidics

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Rapid AM Prototyping

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-Resolution (25-50 µm) Photopolymer Resin | The core material. Biocompatible (ISO 10993) formulations are essential for cell culture or drug testing applications. Low viscosity and fast curing kinetics enable fine features and rapid printing. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA, ≥99%) | Primary wash solvent to remove uncured, liquid resin from the printed device's channels and surfaces post-print. Critical for achieving clean, functional microchannels. |

| Post-Curing UV Chamber (385-405 nm) | Provides uniform, high-intensity UV light for final cross-linking of the polymer. This step is mandatory to achieve reported mechanical properties, solvent resistance, and biocompatibility. |

| Surface Passivation Reagent (e.g., PEG-silane) | For cell-based studies. A treatment solution applied to cured resin channels to reduce non-specific cell adhesion and protein binding, mimicking the inertness of PDMS. |

| Biocompatible Bonding Agent (e.g., silicone sealant, OEM glue) | Used to seal a printed open-channel device to a flat substrate (e.g., glass slide) or to attach fluidic connectors. Must be chemically compatible and non-cytotoxic. |

| Validation Dyes (e.g., Food dyes, Fluorescein) | Aqueous solutions used for rapid, visual functional testing of device integrity, flow patterning, and mixing performance immediately after fabrication. |

Key Microfluidic Features Enabled by Modern 3D Printing

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing techniques for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, modern additive manufacturing has transcended its role as a mere prototyping tool. It now enables the direct fabrication of devices with intricate, three-dimensional architectures that are difficult or impossible to achieve with traditional lithography. This application note details the key microfluidic features unlocked by contemporary 3D printing, providing protocols for their implementation and characterizing their performance.

Key Printable Features & Quantitative Performance

The following features represent a paradigm shift in device design and functionality.

Table 1: Key 3D-Printed Microfluidic Features and Performance Data

| Enabled Feature | Description & Advantage | Achievable Dimension / Fidelity | Representative Performance Metric | Primary 3D Printing Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True 3D Channels | Helical, vertically overlapping, and tortuous internal pathways for enhanced mixing, longer path length in compact footprint. | Channel diameter: 100 - 500 µm. Vertical pitch: as low as 200 µm. | Mixing efficiency >90% within 5 mm channel length at Re ~1. | Projection Microstereolithography (PµSL), Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) |

| Integrated Valves & Pumps | Monolithically printed, actuatable elements (e.g., diaphragm valves, peristaltic pumps) for fluid control without assembly. | Membrane thickness: 150 - 300 µm. Actuation chamber volume: 1 - 10 nL. | Valve response time <50 ms. Pumping rates of 1 - 100 µL/min. | Digital Light Processing (DLP) with elastomeric resins, Multi-material PolyJet |

| High-Aspect-Ratio Structures | Tall, thin walls and deep reservoirs maximizing surface area for cell culture or filtration. | Aspect ratios (Height:Width) of 30:1 to 50:1. | Surface area increase up to 15x versus planar chip of same footprint. | PµSL, Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) based VAT Polymerization |

| Sub-100 µm Voxel Features | Ultra-fine internal textures, porous matrices, and micro-nozzles for droplet generation. | Minimum feature size: 10 - 25 µm (2PP), 25 - 50 µm (high-res DLP/PµSL). | Droplet generation consistency: CV <3% at 50 µm diameter. | Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP), High-Resolution DLP |

| Multimaterial & Gradient Structures | Spatial variation in material properties (e.g., stiffness, hydrophobicity) within a single device. | Material interface resolution: ~100 µm. Hardness gradient range: Shore A 50 to Shore D 85. | Region-selective cell adhesion (>80% difference). | Material Jetting (PolyJet), Multi-wavelength VAT Polymerization |

| Embedded Optical Elements | Integrated lenses, waveguides, and windows for in-situ detection and imaging. | Lens diameter: 300 - 2000 µm. Surface roughness (Sa): <10 nm (post-polished). | Signal collection efficiency increase of 200-300%. | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) with transparent filament, DLP with clear resin |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a 3D Helical Mixer via DLP Printing

Objective: To fabricate and characterize a microfluidic device with a 3D helical mixing channel for rapid reagent lamination.

Materials: Biocompatible, clear photopolymer resin (e.g., PEGDA-based); Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA); DLP 3D printer with XY resolution ≤50 µm; Compressed air source; UV post-curing chamber.

Procedure:

- Design: Create a 3D model with a helical channel (e.g., 300 µm diameter, 500 µm vertical pitch, 5 full turns). Include 1.5 mm inlet/outlet ports. Use computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation software to predict mixing performance.

- Print Preparation: Slice the model with layer thickness set to 25-50 µm. Ensure support structures are generated only for external overhangs, not within the internal channel.

- Printing: Load resin into the vat. Initiate the print. The process is automated, with each layer exposed by the projected UV pattern.

- Post-Processing: a. Carefully remove the print from the build platform. b. Submerge in IPA and agitate gently for 5 minutes to remove uncured resin. c. Blow-dry with clean, compressed air to clear channels. d. Cure the device in a UV chamber for 10-15 minutes to achieve final mechanical properties.

- Characterization: Connect syringe pumps to inlets. Inject two streams of dyed (e.g., blue/yellow food dye) and clear water at equal flow rates (e.g., 10 µL/min). Capture microscope images downstream and analyze pixel intensity variance to calculate mixing index.

Protocol 2: Monolithic Integration of a Diaphragm Valve via Multi-material Jetting

Objective: To print a functional, membrane-based valve within a flow channel without assembly.

Materials: Multi-material 3D printer (e.g., PolyJet); Rigid photopolymer (VeroClear/RGD810); Elastomeric photopolymer (Agilus30/FLX989); Support material (SUP705); Water jet station.

Procedure:

- Design: Model a flow channel (500 µm x 500 µm) with an enlarged chamber above it. The chamber roof is designed as a thin diaphragm (200 µm thick). Include a separate control channel port leading to the top of this diaphragm chamber.

- Material Assignment: Assign the main device body and channel walls as the rigid material. Assign the diaphragm layer as the elastomeric material. All internal voids are automatically assigned as support material.

- Printing: Send the file to the printer. The printer will jet and UV-cure all materials layer-by-layer, creating a fully integrated, multi-material part.

- Support Removal: Use a high-pressure water jet station to meticulously remove all liquid support material from the channels and chambers.

- Testing: Connect the main flow channel to a fluid reservoir and a pressure sensor. Connect the control port to a pneumatic solenoid. Apply a control pressure (0-30 psi) to deflect the diaphragm into the flow channel. Measure the pressure drop across the main channel to characterize the valve's shut-off performance.

Visualization of Workflows

Workflow for Fabricating a 3D Printed Helical Mixer

Multi-material Jetting Process for Integrated Valves

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for 3D-Printed Microfluidics

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Photopolymer Resins | Form the device matrix. Require biocompatibility (if for bio-apps), low autofluorescence, and tunable mechanical properties. | PEGDA (Polyethylene glycol diacrylate), Methacrylate-based resins (e.g., IP-L 780, PRO-BLK 10). |

| Elastomeric Photopolymers | Enable integrated flexible components like valves, pumps, and seals. Characterized by Shore hardness and elongation at break. | Agilus30 (Stratasys), Flexible (Formlabs), Elastic 50A Resin (3D Systems). |

| Support Removal Solvents | Dissolve sacrificial support material to reveal internal channels without damaging fine features. | Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), Limonene-based solutions (for some resins), Sodium Hydroxide solution (for PVA supports). |

| Surface Passivation Agents | Coat printed channel interiors to reduce non-specific adsorption of proteins or cells, and to modify wettability. | Pluronic F-127, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), (1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyl)trichlorosilane. |

| Bonding/Sealing Agents | Adhere 3D-printed parts to glass slides, membranes, or other substrates to enclose channels or create interfaces. | Optically clear adhesive (OCA) films, UV-curable glue (NOA 81), Silicone-based sealants. |

| Functionalization Reagents | Covalently attach biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, peptides) to the polymer surface for cell capture or sensing. | Sulfo-SANPAH (for acrylate surfaces), EDC/NHS chemistry, Biotin-PEG-Acrylate (incorporated during printing). |

This document provides a comparative overview of four core 3D printing technologies—Stereolithography (SLA), Digital Light Processing (DLP), PolyJet, and Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)—within the context of rapid prototyping for microfluidic device research. These technologies are evaluated for their capability to produce devices with the requisite feature resolution, channel integrity, surface finish, and biocompatibility necessary for applications in diagnostics, drug development, and biological research.

Technology Application Notes

Stereolithography (SLA)

Principle: A laser beam selectively photopolymerizes a liquid thermoset resin layer-by-layer.

- Key Advantage: Excellent feature resolution and smooth surface finish.

- Primary Limitation: Limited material choice; resins may require careful post-processing for biocompatibility.

- Microfluidic Relevance: Suitable for creating master molds for soft lithography (PDMS casting) and direct printing of transparent devices with embedded channels.

Digital Light Processing (DLP)

Principle: An entire layer of resin is cured simultaneously by projecting a digital light image.

- Key Advantage: Faster print times per layer compared to laser-based SLA.

- Primary Limitation: The pixel size of the projector limits the in-plane (XY) resolution.

- Microfluidic Relevance: Efficient for rapid iteration of microfluidic designs with good resolution, though potential for voxel-line artifacts on channel walls.

PolyJet / Material Jetting (MJP)

Principle: Inkjet-style print heads jet photopolymer materials which are instantly cured by UV light.

- Key Advantage: High resolution and the unique ability to print multiple materials (including flexible and rigid photopolymers) in a single build.

- Primary Limitation: High cost; support material removal can be challenging for complex, enclosed microchannels.

- Microfluidic Relevance: Enables fabrication of devices with integrated flexible membranes (e.g., for valves, pumps) and varied mechanical properties without assembly.

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM)

Principle: A thermoplastic filament is heated and extruded through a nozzle, depositing material layer-by-layer.

- Key Advantage: Low cost, wide material availability (e.g., ABS, PLA, biocompatible polycarbonate).

- Primary Limitation: Lower resolution, visible layer lines, and challenges in creating watertight, transparent devices.

- Microfluidic Relevance: Best suited for prototyping fluidic housings, connectors, or large-scale channel features where optical clarity and high resolution are not critical.

Comparative Quantitative Data

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications for Microfluidic Prototyping

| Parameter | SLA | DLP | PolyJet/MJP | FDM | Notes for Microfluidics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical XY Resolution (µm) | 25-150 | 30-100 | 20-85 | 100-400 | Determines minimum feature size (channel width, pillar diameter). |

| Typical Layer Height (µm) | 10-150 | 10-100 | 16-30 | 50-400 | Impacts Z-axis resolution, channel roof quality, and stair-stepping artifacts. |

| Print Speed | Medium | Fast (per layer) | Medium-Slow | Slow-Medium | DLP excels at flat, small-area layers; speed depends on volume and resolution. |

| Biocompatible Materials | Limited, Specific Resins | Limited, Specific Resins | Limited, Specific Resins | Good Selection (e.g., PP, PC, PETG) | Requires validation for cell culture or biological fluids. |

| Channel Transparency | High (Post-processed) | High (Post-processed) | High | Low-Medium | Critical for microscopy. SLA/DLP/PolyJet offer optical clarity. |

| Surface Roughness (Ra, µm) | 0.1-1.0 | 0.3-1.5 | 0.2-0.8 | 5-20 | Roughness affects fluid flow, cell adhesion, and optical clarity. |

| Multi-Material Capability | No | No | Yes | Limited (Dual Extrusion) | PolyJet uniquely allows simultaneous rigid/soft materials for integrated features. |

| Relative Cost of Printer | Medium-High | Medium | High | Low | FDM is most accessible; material costs vary significantly. |

Table 2: Suitability for Common Microfluidic Prototyping Tasks

| Prototyping Task | Recommended Technology (Ranked) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Master Mold | SLA > DLP > PolyJet > FDM | SLA provides the best combination of smooth vertical walls and fine detail. |

| Transparent, Monolithic Device | SLA / DLP > PolyJet > FDM | SLA/DLP resins yield watertight, clear devices suitable for imaging. |

| Device with Integrated Valve | PolyJet > SLA/DLP > FDM | PolyJet can print elastomeric membranes and rigid structures in one process. |

| Low-Cost, Iterative Prototyping | FDM > DLP > SLA > PolyJet | For large, non-transparent components where cost and speed are primary. |

| Biocompatible Fluidic Path | FDM (with specific filament) > SLA/DLP/PolyJet (validated resin) | Depends on chemical/biological resistance; often requires post-curing & testing. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Microfluidic Mixer via SLA for PDMS Soft Lithography

Objective: To create a high-resolution master mold for replicating PDMS-based microfluidic gradient generators. Materials: Biocompatible SLA resin (e.g., Formlabs Dental SG or equivalent), IPA (≥99%), PPE, SLA printer, UV post-curing station, silanizing agent (Trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane). Procedure:

- Design: Create the positive channel design (height: ~100-200 µm) in CAD. Export as STL with appropriate orientation (minimizing supports on critical channel surfaces).

- Printing: Load the STL into the printer slicer. Generate supports with a touchpoint size of 0.3-0.5 mm. Initiate the print using manufacturer-recommended settings for high resolution.

- Post-Processing:

- Washing: Transfer the printed part to an IPA bath. Agitate gently for 3-5 minutes to remove uncured resin.

- Drying: Air dry or use compressed air to remove all IPA.

- Post-Curing: Place the part in a UV curing chamber for 15-30 minutes per side to ensure full polymerization and stability.

- Mold Preparation: Place the cured resin master in a desiccator with a few drops of silanizing agent for 1 hour under vacuum. This creates an anti-adhesion layer for PDMS release.

- PDMS Casting: Pour a 10:1 mixture of PDMS base and curing agent over the master, degas, and cure at 65°C for 2 hours. Carefully peel the PDMS replica from the master.

Protocol 2: Direct Printing of a Cell Culture Chamber via DLP

Objective: To directly fabricate a sterile, transparent microfluidic chamber for adherent cell culture. Materials: Biocompatible, cell-culture validated DLP resin (e.g., BEGO MED610 or Asiga BIO MED), IPA (≥99.7%), USP Glycerin, UV post-curing station, sterile PBS, 70% ethanol, UV sterilizer. Procedure:

- Design & Print: Design a chamber with inlet/outlet ports and a culture area (~1 mm height). Print using the DLP printer's "high resolution" mode.

- Post-Processing:

- Wash in IPA for 3 minutes, followed by a second wash in fresh IPA for 2 minutes.

- Rinse the device in a bath of USP Glycerin for 1 minute to reduce IPA-induced surface tension and potential cracking.

- Rinse immediately with copious amounts of sterile, deionized water.

- Post-cure under UV light for 30 minutes, submersed in water to minimize oxygen inhibition and increase biocompatibility.

- Sterilization & Preparation:

- Soak the device in 70% ethanol for 20 minutes.

- Rinse thoroughly with sterile PBS 3x.

- Expose the internal channels to UV light in a biosafety cabinet for 30 minutes prior to cell seeding.

- Cell Seeding: Introduce cell suspension via the inlet port using a pipette or syringe pump, allow cells to adhere, then connect to a perfusion system if required.

Visualization of Technology Selection Workflow

Title: Decision Workflow for Selecting 3D Printing Technology in Microfluidics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for 3D Printed Microfluidic Device Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible / Class I Certified Resins | Enable direct contact with biological fluids or cells; reduce cytotoxicity. | Formlabs Biocompatible Resin, Asiga BIO MED, BEGO MED610. Must be validated for specific application. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA, ≥99%) | Primary solvent for washing uncured resin from vat polymerization (SLA/DLP) prints. | High purity reduces residue. Often used in a two-bath system. |

| UV Post-Curing Chamber | Ensures complete polymerization of printed parts, improving mechanical properties and biocompatibility. | Critical for achieving stable, long-term performance of resin-based devices. |

| Silanizing Agent (e.g., Fluorosilane) | Treats master molds to facilitate easy release of PDMS casts, preventing damage. | Applied via vapor deposition in a desiccator. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | Elastomer used with master molds to create gas-permeable, optically clear microfluidic devices. | Sylgard 184 is standard; mixing ratio (e.g., 10:1) controls stiffness. |

| Specific Thermoplastic Filaments | Provide chemical resistance or biocompatibility for FDM-printed fluidic components. | Polypropylene (PP), Polycarbonate (PC), PETG. Require printer compatibility. |

| Plasma Surface Treater | Activates PDMS and plastic/glass surfaces for irreversible bonding to create sealed channels. | Creates hydrophilic surfaces necessary for permanent sealing. |

| Syringe Pumps & Tubing | Provide controlled fluid flow through printed devices for testing and application. | Essential for perfusion culture, shear stress studies, and device characterization. |

Application Notes

In the context of 3D printing for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, the selection of materials is governed by a critical triad: biocompatibility for cell culture or bioassays, optical transparency for visualization and detection, and sufficient mechanical properties for device integrity and function.

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility is non-negotiable for devices intended for biological applications. It ensures minimal undesired interaction between the device material and biological entities (cells, proteins, reagents). For 3D printed microfluidics, this often requires post-processing to remove cytotoxic residues (e.g., uncured monomers, photoinitiators) from the printing process. Assessment involves cytotoxicity assays (e.g., ISO 10993-5) and cell adhesion/proliferation studies.

Optical Transparency

High transparency across visible and UV spectra is essential for real-time microscopic observation, spectrophotometric detection, and fluorescent imaging. Many as-printed polymers exhibit cloudiness due to light scattering from microstructural imperfections. Achieving clarity often involves optimizing print parameters (layer height, curing) and applying post-print polishing or coating protocols.

Mechanical Properties

Mechanical strength determines a device's durability and its ability to withstand operational pressures and connections. Key properties include tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and fracture toughness. For microfluidics, resistance to solvent-induced swelling and the ability to form leak-free seals (often via bonding) are paramount.

Table 1: Common 3D Printing Materials for Microfluidics

| Material (Trade Name/Class) | Biocompatibility (Cell Viability %) | Transparency (Haze %) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Young's Modulus (MPa) | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereolithography (SLA) Resin (Standard) | ~50-70 (post-cured) | 85-90 (High Haze) | 45-65 | 2000-2500 | Requires extensive ethanol washing and UV post-cure; often cytotoxic without treatment. |

| SLA Resin (Biocompatible, e.g., Dental SG) | >95 (post-cured & washed) | 80-85 | 50-60 | 2200-2400 | Designed for biomedical contact; ethanol extraction is still critical. |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) Resin (Clear) | ~75-85 | 88-92 (Moderate Haze) | 40-55 | 1800-2200 | Better inherent clarity than standard SLA; biocompatibility varies by formulation. |

| PolyJet (VeroClear) | ~60-75 | 90-93 | 50-60 | 2000-3000 | Multi-material capability; support removal can leave residues affecting bio-assays. |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) - ABS | <50 (poor) | Opaque | 30-40 | 2000 | Generally unsuitable for live-cell applications; used for structural prototyping only. |

| FDM - PLA | ~70-80 (surface treated) | Semi-translucent | 50-70 | 3000-3500 | More biocompatible than ABS; can be surface smoothed (e.g., with acetone vapor) for better sealing. |

| 2-Photon Polymerization (2PP) - IP-S | >90 | >95 (Excellent) | 100-120 | 5000-6000 | High-resolution, excellent properties; cost-prohibitive for large devices. |

Table 2: Post-Processing Impact on Material Properties

| Post-Processing Method | Effect on Biocompatibility (Viability Δ%) | Effect on Transparency (Haze Δ%) | Effect on Tensile Strength (Δ%) | Protocol Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol Wash (SLA/DLP) | +40 to +60 | +5 (Improvement) | -5 to -10 | 30-60 min + drying |

| UV Post-Curing | -10 to +5 (Can leach initiators) | -2 to -5 (Can yellow) | +15 to +25 | 15-60 min |

| Heat Treatment (PLA) | +10 to +15 (If sterilizable) | -20 (Can reduce clarity) | ±5 | 1-2 hrs |

| Oxygen Plasma Treatment | +20 (Improves wettability) | Minimal | Minimal (surface only) | 1-5 min |

| Solvent Vapor Smoothing (ABS) | -30 (Often toxic) | -50 (Greatly improves) | -15 | 10-30 min |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Biocompatibility via Direct Contact Cytotoxicity Assay (ISO 10993-5)

Objective: To evaluate the cytotoxicity of a 3D printed microfluidic device material using L929 fibroblast cells. Materials:

- 3D printed test specimens (sterilized)

- L929 fibroblast cell line

- Complete cell culture medium (DMEM + 10% FBS)

- 24-well tissue culture plate

- AlamarBlue or MTT reagent

- CO2 incubator

- Microplate reader

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Print 10mm diameter discs (2mm thick). Post-process per intended protocol (e.g., wash, cure). Sterilize via 70% ethanol immersion (30 min) and UV exposure (30 min per side).

- Cell Seeding: Seed L929 cells in a 24-well plate at 1x10^4 cells/well in 1 mL medium. Incubate for 24 hrs (37°C, 5% CO2) to form a semi-confluent monolayer.

- Direct Contact: Carefully place one sterilized test specimen directly onto the cell monolayer in triplicate wells. Include a negative control (cells alone) and a positive control (e.g., latex).

- Incubation: Incubate for 24 hours.

- Viability Assessment: Aspirate medium. Add fresh medium containing 10% AlamarBlue. Incubate for 4 hrs. Measure fluorescence (Ex560/Em590) using a microplate reader.

- Analysis: Calculate cell viability as a percentage of the negative control. Viability >70% is generally considered non-cytotoxic.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Transparency and Haze Measurement

Objective: To measure the total light transmittance and haze of a 3D printed material sample. Materials:

- 3D printed samples (polished and unpolished, 1mm thick, optically flat)

- Haze meter or UV-Vis spectrophotometer with integrating sphere

- Calibration standards

Methodology:

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the haze meter or spectrophotometer using the provided air blank and standard reference.

- Sample Mounting: Securely mount the 3D printed sample in the specimen holder.

- Total Transmittance (Tt): Measure the total amount of light transmitted through the sample.

- Diffuse Transmittance (Td): Measure the amount of light scattered by more than 2.5 degrees from the incident beam.

- Calculation: Calculate Haze (%) using the formula: Haze (%) = (Td / Tt) x 100. A lower haze value indicates greater clarity.

- Reporting: Report both Total Transmittance (%) and Haze (%) for each sample condition.

Protocol 3: Tensile Testing for Mechanical Property Characterization

Objective: To determine the tensile strength and Young's modulus of a 3D printed polymer. Materials:

- 3D printed tensile "dog-bone" specimens (Type V per ASTM D638)

- Universal tensile testing machine

- Calipers

Methodology:

- Specimen Preparation: Print at least 5 dog-bone specimens with build orientation aligned with the tensile axis. Condition specimens at standard temperature/humidity (e.g., 23°C, 50% RH) for 48 hrs.

- Dimensional Measurement: Use calipers to precisely measure the width and thickness of the narrow gauge section of each specimen.

- Machine Setup: Mount the specimen in the grips of the tester. Set the grip separation and crosshead speed (typically 5 mm/min for plastics).

- Testing: Initiate the test. The machine will apply a uniaxial load until specimen failure. Record the force vs. displacement data.

- Data Analysis:

- Tensile Strength at Break: Calculate as maximum load / original cross-sectional area.

- Young's Modulus: Calculate the slope of the initial linear portion of the stress-strain curve.

Diagrams

Title: Material Validation Workflow for 3D Printed Microfluidics

Title: Cytotoxicity Pathways from Material Leachables

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Biocompatible SLA/DLP Resins (e.g., Formlabs BioMed, PEGDA-based) | Photopolymer resins formulated with reduced cytotoxic components, enabling direct printing of cell-compatible structures after proper washing. |

| AlamarBlue / MTT Cell Viability Reagents | Colorimetric or fluorometric indicators of metabolic activity, used to quantify cytotoxicity of printed materials in ISO 10993-5 assays. |

| Anhydrous Ethanol (200 proof, HPLC grade) | Primary solvent for post-print washing to extract unreacted monomers and photoinitiators from resin-based prints, critical for biocompatibility. |

| (3-Acryloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane | A silane coupling agent used to surface-functionalize 3D printed channels, improving hydrophilicity and biomolecule bonding for assays. |

| Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Sylgard 184 | The gold-standard elastomer for microfluidics; often used in hybrid devices with 3D printed rigid components or molds. |

| Oxygen Plasma System | Used for surface activation of printed plastics to achieve permanent, high-strength bonding of device layers and to modify wettability. |

| UV Ozone Cleaner | Alternative to plasma for surface activation and for degrading organic contaminants to improve bonding and optical clarity. |

| Automated Liquid Handling System | Enables precise, reproducible filling of microfluidic channels with cells, hydrogels, or reagents for high-throughput screening applications. |

The advent of desktop 3D printing has fundamentally shifted the paradigm for prototyping microfluidic devices. Traditionally reliant on cleanroom-based photolithography—a process characterized by high cost, limited access, and slow iteration—microfluidic innovation was bottlenecked. Within the thesis context of 3D printing for rapid prototyping, this democratization enables research labs to conduct in-house design, fabrication, and testing cycles within hours, rather than weeks. This agility accelerates research in cell biology, point-of-care diagnostics, and drug development, allowing for rapid optimization of droplet generators, organ-on-a-chip platforms, and gradient generators.

Quantitative Data: Comparing Fabrication Techniques

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Microfluidic Device Prototyping Techniques

| Parameter | Traditional PDMS Soft Lithography | Commercial High-Res SLA/DLP | Desktop FDM Printing | Experimental μSLA (355nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Feature Resolution | 1 – 100 µm | 25 – 100 µm | 100 – 300 µm | 10 – 50 µm |

| Typical Biocompatibility | Excellent (PDMS) | Moderate (Requires post-processing) | Low (Potential for leaching) | Moderate to High (Depends on resin) |

| Setup/Capital Cost (USD) | $100k+ (Cleanroom) | $2,000 – $20,000 | $300 – $3,000 | $5,000 – $15,000 |

| Cost per Device Prototype | $50 – $200 | $2 – $20 | $1 – $10 | $5 – $30 |

| Design-to-Device Time | 1 – 7 days | 1 – 4 hours | 2 – 6 hours | 30 mins – 2 hours |

| Optical Clarity | High | Moderate to High | Low | High |

| Key Strength | Gold-standard resolution & biocompatibility | Good balance of speed, cost, resolution | Extreme accessibility & material variety | Near-cleanroom resolution on desktop |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid Prototyping of a Droplet Generator via Desktop DLP Printing Objective: To fabricate and test a flow-focusing droplet generator for monodisperse water-in-oil emulsion formation. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method: 1. Design: Create a 3D model of the device (channel width: 150 µm, height: 150 µm, flow-focusing junction: 100 µm) using CAD software (e.g., Autodesk Fusion 360, SolidWorks). Include fluidic ports for 1/16" outer diameter tubing. 2. Preparation for Print: Import the STL file into the printer's slicing software (e.g., Chitubox). Orient the device at a 45-degree angle to minimize layer artifacts on critical channel surfaces. Generate supports with light touchpoints. 3. Printing: Use a biocompatible, PEGDA-based resin. Initiate printing. Post-print, immerse the device in isopropanol in an ultrasonic bath for 3 minutes to remove uncured resin. Cure under 405 nm UV light for 15 minutes. 4. Bonding & Assembly: Plasma treat the device and a flat printed substrate for 60 seconds. Bring surfaces into immediate contact. Bake at 60°C for 15 minutes to enhance bond strength. Insert and glue PEEK tubing into port holes. 5. Testing & Validation: Connect syringe pumps for the aqueous (1% fluorescent dye) and oil (HFE-7500 with 2% surfactant) phases. Initiate flow (Qcontinuous: 100 µL/min, Qdispersed: 20 µL/min). Image droplet formation using a high-speed camera mounted on an inverted microscope. Analyze droplet diameter and uniformity using ImageJ software.

Protocol 2: Surface Treatment for Enhanced Biocompatibility of Printed Devices Objective: To render a 3D-printed resin device hydrophilic and biologically inert for mammalian cell culture. Method: 1. Post-Cure Cleaning: After initial UV cure, soak the device in ethanol for 2 hours, then in deionized water for 1 hour with gentle agitation. 2. Surface Coating: Prepare a 1 mg/mL solution of Poly-L-lysine-graft-polyethylene glycol (PLL-g-PEG) in HEPES buffer. 3. Incubation: Fill the channels of the device with the PLL-g-PEG solution and incubate at room temperature for 1 hour. 4. Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse channels with sterile PBS buffer (pH 7.4) to remove non-adsorbed polymer. 5. Validation: Assess hydrophilicity via contact angle measurement. Validate biocompatibility by seeding HUVEC cells into the channel and assessing viability (>90% expected) via live/dead assay after 24 hours.

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Title: Rapid Prototyping Iterative Cycle

Title: Core Thesis Research Pillars

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D-Printed Microfluidics Prototyping

| Item Name | Category | Function & Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible (PEGDA-based) Resin | 3D Printing Material | A photopolymer resin formulated for reduced cytotoxicity, enabling direct cell culture within printed devices. |

| PLL-g-PEG | Surface Coating | A copolymer that adsorbs to surfaces, creating a bio-inert, hydrophilic layer that prevents non-specific protein and cell adhesion. |

| HFE-7500 with 2% Krytox-JW | Fluidics Reagent | A fluorinated oil/surfactant system for creating stable, biocompatible water-in-oil droplets for digital assays. |

| Oxygen-Plasma Cleaner | Equipment | Treats printed resin surfaces to create temporary hydrophilic surfaces and enable permanent bonding of device layers. |

| PEEK Tubing (1/16" OD) | Fluidic Interconnect | Inert, high-pressure tubing for connecting syringes and pumps to microfluidic devices with minimal dead volume. |

| Digital Syringe Pump | Equipment | Provides precise, pulseless flow control for introducing reagents, cells, or oil phases into microfluidic channels. |

Step-by-Step Workflows and Cutting-Edge Biomedical Applications

Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) Principles for Microfluidics

This application note details specific Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM) principles for the rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, within the broader research context of a thesis on advanced 3D printing techniques. The goal is to enable researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to translate complex microfluidic designs into functional, monolithic prototypes with minimal iteration, leveraging the unique capabilities of vat photopolymerization (e.g., SLA, DLP), material jetting, and high-resolution powder bed fusion.

Foundational DfAM Principles for Microfluidics

Principle 1: Embracing Monolithic Design

Move away from designs dependent on multi-part assembly. 3D printing enables the integration of features like mixers, valves, and chambers into a single, leak-free component.

Principle 2: Designing for the Printing Axis (Build Orientation)

Channel orientation critically impacts resolution, surface finish, and success rate. Vertical channels require support structures and may have elliptical distortion, while horizontal channels have superior resolution but can trap resin.

Principle 3: Optimizing Channel Geometry for Printability

Avoid unsupported horizontal spans and design channels with aspect ratios suitable for the printer's resolution. Incorporate rounded corners to reduce stress concentrations and improve fluid flow.

Principle 4: Managing Supports and Post-Processing

Strategically place supports on non-critical external surfaces to preserve internal channel integrity. Design access points for support material removal from internal channels.

Principle 5: Material and Biocompatibility Considerations

Select resins or polymers certified for biocompatibility (e.g., USP Class VI, ISO 10993) if used with biological samples. Understand material properties like permeability, autofluorescence, and chemical resistance.

Quantitative Data on Print Performance

Table 1: Comparison of 3D Printing Technologies for Microfluidics

| Technology | Typical Lateral Resolution (µm) | Typical Vertical Resolution (µm) | Minimum Channel Size (µm) | Common Materials | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereolithography (SLA) | 25-150 | 25-200 | ~100 | Acrylate resins, biocompatible resins | High resolution, smooth surface finish | Limited material choice, may require post-curing |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | 30-100 | 25-150 | ~50-100 | Acrylate and epoxy resins | Faster print speed for full layers | Potential pixelation artifacts |

| Material Jetting (PolyJet) | 20-50 | 16-30 | ~200 | Acrylic-based photopolymers | Multi-material printing, high detail | Channels prone to clogging with support material |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) | <1 | <1 | ~1 | Custom photoresins | Sub-micron resolution | Extremely slow, very small build volume |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | 200-500 | 100-300 | ~500 | ABS, PLA, PP | Low cost, wide material range | Low resolution, anisotropic strength, leakage |

Table 2: Impact of Build Orientation on Channel Fidelity

| Channel Orientation | Dimensional Accuracy | Surface Roughness (Ra) | Risk of Feature Collapse | Support Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal (parallel to build plate) | High | Low (top surface) to High (bottom) | Low for small spans | No |

| Vertical (perpendicular to build plate) | Medium (may ovalize) | Medium | Low | Yes (external) |

| 45° Angle | Medium-High | Medium | Medium | Yes |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of a Monolithic Mixing Device

Protocol 1: Design and Printing of a 3D Serpentine Micromixer

Objective: To fabricate and characterize a monolithic 3D-printed micromixer for rapid fluid diffusion.

Materials & Equipment:

- CAD Software (e.g., Fusion 360, SolidWorks)

- High-Resolution DLP/SLA 3D Printer (e.g., Asiga, Formlabs)

- Biocompatible, Clear Photoresin (e.g., Formlabs Biomedical Clear, or similar)

- Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) ≥ 99%

- Ultrasonic Cleaner

- UV Post-Curing Chamber

- Compressed Air or Nitrogen Gun

- Syringe Pumps

- Inlet/Outlet Connectors (e.g., barbed luer fittings)

- Food Dye or Analytical Tracers for Testing

Procedure:

- Design (DfAM Application):

- Model a 3D serpentine channel with a circular cross-section of 300 µm diameter.

- Incorporate inlet and outlet ports with widened, tapered receptacles (1.5 mm diameter) to facilitate tubing insertion.

- Add a 0.5 mm thick, easily breakable support lattice outside the main device body to connect the port openings to the build plate, keeping all channel interiors completely support-free.

- Orient the device so the channel axis is primarily horizontal to maximize XY resolution.

- Export design as an STL file with appropriate tolerance (e.g., 0.01 mm).

Preparation & Printing:

- Import STL into printer slicer software.

- Automatically generate supports for the external support lattice and device base. Manually ensure no supports are generated inside channels.

- Set layer thickness to 25-50 µm, depending on printer capability.

- Initiate print.

Post-Processing:

- Carefully remove the build plate from the printer.

- Gently detach the external support lattice from the device ports.

- Immerse the device in IPA for 5 minutes in an ultrasonic cleaner to remove uncured resin.

- Rinse with fresh IPA and dry with a stream of clean, dry air or nitrogen.

- Post-cure the device in a UV chamber for 15-20 minutes per side, as per resin specifications.

Testing & Characterization:

- Connect syringe pumps to inlets via tubing and fittings.

- Infuse two streams—one of deionized water, the other of dyed water—at equal flow rates (e.g., 10 µL/min each).

- Visually or microscopically observe mixing efficiency along the serpentine channel.

- Quantify mixing index (η) by analyzing image intensity profiles across the channel width at multiple points downstream using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Visualization: DfAM Workflow for Microfluidics

Title: DfAM Workflow for 3D Printed Microfluidic Prototypes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Prototyping and Testing

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photoresin (e.g., Formlabs Biomedical Clear, Dental SG) | Primary printing material for cell-compatible devices. | Verify USP Class VI or ISO 10993 certification. Check optical clarity and permeability for your application. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA), 99%+ | Washing uncured resin from printed parts. | High purity reduces contamination. Use in well-ventilated areas. |

| UV Post-Curing Chamber (e.g., Formlabs Form Cure) | Final polymerization of washed prints to achieve final mechanical properties and biocompatibility. | Ensures consistent, wavelength-appropriate curing as per resin specs. |

| Cytocompatible Sterilant (e.g., Ethanol 70%, Ethylene Oxide) | Sterilization of devices prior to cell culture. | Avoid autoclaving as it may deform prints. EtO is effective but requires aeration. |

| PDMS or Silicone Sealant (Biocompatible) | Sealing interfaces or bonding 3D-printed parts to glass slides or other substrates. | Ensure compatibility with printed material and assay conditions (e.g., non-leaching). |

| Fluidic Connectors (e.g., Barbed Luer, Press-fit) | Connecting microfluidic devices to pumps and tubing. | Design inlet/outlet ports to match connector size for a leak-free seal. |

| Fluorescent Tracers or Beads | Visualizing flow patterns, quantifying mixing efficiency, or measuring velocities. | Select size appropriate for channel dimensions. Check for adsorption to printed material. |

| Surface Passivation Agent (e.g., Pluronic F-127, BSA) | Treating channel walls to minimize nonspecific adsorption of proteins or cells. | Critical for quantitative bioassays and maintaining cell viability. |

Abstract This application note details a standardized workflow for transitioning from a digital CAD model to a functional, leak-free microfluidic prototype, framed within a thesis on advanced 3D printing techniques for rapid prototyping in research. The protocol emphasizes design for additive manufacturing (DFAM), post-processing, and validation, targeting researchers and professionals in drug development requiring quick iteration of microfluidic architectures.

1. Introduction Within rapid prototyping research, the gap between a computational design and a physically reliable device is bridged by a meticulous workflow. This protocol addresses critical bottlenecks—fidelity, sealing, and surface quality—specific to microfluidics, leveraging vat photopolymerization (e.g., DLP, SLA) and material jetting 3D printing techniques for their superior resolution.

2. Materials & Reagent Solutions (The Scientist's Toolkit)

| Item/Category | Specific Example/Product | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Printing Resin | Formlabs Biomedical Clear Resin (RGUS) | High-transparency, biocompatible photopolymer for DLP/SLA printing of channel structures. |

| Support Material | Formlabs Basic Support Resin | Provides scaffolding for overhangs; dissolved post-print. |

| Solvent for Post-Processing | Isopropanol (IPA), ≥99% | Primary wash to remove uncured resin from printed parts and channels. |

| Post-Curing Device | Formlabs Form Cure | UV light chamber for final polymerization, enhancing mechanical strength and biocompatibility. |

| Surface Passivation Agent | (3-Glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) | Functionalizes channel surfaces to reduce analyte adsorption and control hydrophilicity. |

| Bonding Agent | Uncured resin layer or silicone adhesive | Creates a permanent, leak-free seal between printed layers or to a substrate. |

| Validation Dye | Food dye (Blue #1) or Fluorescein | Aqueous solution for visual and fluorescent leak testing and flow visualization. |

| Precision Pressure Source | Elveflow OB1 MK4 Pressure Controller | Delivers precise, pulseless pressure to drive fluids for device characterization. |

3. Core Workflow Protocol Note: All steps involving solvents or UV light require appropriate PPE (safety glasses, nitrile gloves, lab coat).

3.1. CAD Design & Preparation (Pre-Print)

- Software: Utilize CAD software (e.g., SolidWorks, Fusion 360, FreeCAD) for design.

- Critical DFAM Parameters:

- Channel Dimensions: Compensate for XY shrinkage (typically 2-4%) and critical feature size (>150 µm recommended for reliable printing).

- Orientation: Angle the device (~20-45°) to minimize stairstepping on channel roofs and reduce large, flat cross-sectional areas.

- Support Strategy: Auto-generate supports with touchpoint size of 0.4-0.6 mm on non-critical external surfaces. Manually add supports to any internal channel overhangs.

- File Export: Slice model using printer-specific software (e.g., PreForm for Formlabs) and export as

.slc,.photon, or printer-native format.

3.2. Printing & Primary Post-Processing

- Printing: Follow manufacturer instructions for selected resin. Record key parameters (Table 1).

- Primary Wash:

- Post-print, immediately submerge the device in IPA in a first wash bath for 5 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Transfer to a second clean IPA bath for an additional 3 minutes.

- For internal channels, use a syringe with IPA to gently flush channels until no oily residue is visible.

- Support Removal: Carefully clip away support structures using flush cutters. Sand touch points with fine-grit (400+) sandpaper if needed for bonding.

- UV Post-Curing:

- Place device in post-curing chamber.

- Cure for 15-20 minutes per side at 60°C (or as per resin datasheet). Ensure all surfaces, especially internal channels, receive UV exposure.

3.3. Sealing & Bonding Protocol

- Method A (Resin Bonding for Enclosed Channels):

- Print device as an open-faced "master" and a flat "lid."

- Lightly coat the bonding surface of the master with a thin layer of fresh, uncured resin using a lint-free wipe.

- Carefully align and place the lid.

- Cure the assembly under a flood UV lamp or in the post-curing chamber for 10 minutes.

- Method B (Adhesive Gasket Bonding):

- Cut a thin PDMS sheet or use a silicone adhesive gasket.

- Align between the printed part and a glass slide.

- Apply uniform pressure using a clamp or weight for 24 hours.

3.4. Functional Validation & Testing

- Leak Test:

- Connect one device inlet to a pressure controller or syringe pump.

- Fill channels with validation dye solution.

- Gradually increase pressure to 2x intended operating pressure (e.g., from 50 kPa to 100 kPa). Hold for 10 minutes.

- Visually inspect for droplets or seepage under a stereomicroscope.

- Fidelity Assessment:

- Image cross-sections of critical channels (e.g., mixers, pores) using optical profilometry or microscopy.

- Measure channel width/height at 3 points along its length. Compare to CAD dimensions.

4. Data Summary & Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Common 3D Printing Techniques for Microfluidics

| Technique | Typical XY Resolution (µm) | Typical Layer Height (µm) | Print Time (for 10x10x5 mm device) | Biocompatibility Post-Cure | Recommended Minimum Channel Size (µm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereolithography (SLA) | 50-140 | 25-100 | ~1.5 hours | Good (with specific resins) | 150 |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | 30-100 | 10-50 | ~0.5 hours | Good (with specific resins) | 100 |

| Material Jetting (PolyJet) | 20-85 | 16-30 | ~0.75 hours | Moderate (requires coating) | 200 |

Table 2: Post-Processing Impact on Dimensional Fidelity (Example Data)

| Post-Curing Time (min) | Shrinkage in X-Y (%) | Shrinkage in Z (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Water Contact Angle (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 48 | 75 |

| 20 (Recommended) | 2.8 | 4.2 | 65 | 78 |

| 30 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 68 | 79 |

5. Visualized Workflows

Title: Core 3D Printing Prototyping Workflow

Title: Iterative Post-Curing Validation Loop

Fabricating Complex 3D Microchannels and Multi-Layer Devices

This application note details advanced 3D printing protocols for fabricating complex, three-dimensional microfluidic networks. Within the broader thesis on rapid prototyping for microfluidics, these methods address the critical challenge of moving from 2D planar designs to true 3D architectures, which are essential for mimicking physiological vasculature, creating high-density fluidic circuits, and integrating multi-functional layers for drug development applications.

Key 3D Printing Techniques & Quantitative Comparison

The selection of a fabrication technique depends on resolution, material, build time, and biocompatibility requirements. The following table summarizes the primary methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of 3D Printing Techniques for Complex Microchannels

| Technique | Lateral Resolution (µm) | Z-Resolution (µm) | Typical Build Time (per cm³) | Biocompatible Material Availability | Key Limitation for 3D Channels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projection Micro-Stereolithography (PµSL) | 1 - 10 | 1 - 10 | 5 - 20 min | High (Acrylates, PEGDA) | Requires support for overhangs |

| Two-Photon Polymerization (2PP) | 0.1 - 0.3 | 0.1 - 0.5 | 60+ min | High (Ormocomp, IP-S) | Extremely slow for large volumes |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | 10 - 50 | 10 - 100 | 1 - 10 min | Moderate (Resins, Hydrogels) | Resolution limited by pixel size |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | 50 - 200 | 50 - 200 | 10 - 30 min | Low (PLA, ABS) | Surface roughness, layer adhesion |

| Inkjet 3D Printing | 20 - 50 | 5 - 20 | 5 - 15 min | Moderate (Acrylics, Silicones) | Material property limitations |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Fabricating 3D Helical & Spiral Microchannels via PµSL

Objective: To create a free-standing, 3D helical microchannel (500 µm diameter, 5-turn helix) for studying shear stress effects on cell cultures.

Materials & Equipment:

- PµSL printer (e.g., Boston Micro Fabrication, BMF)

- Biocompatible resin (e.g., PEGDA 700 Da with 1% w/v LAP photoinitiator)

- Isopropyl alcohol (IPA, 99.9%)

- Nitrogen gun

- UV post-curing chamber (365 nm, 15 mW/cm²)

- Syringe and tubing for fluidic testing.

Methodology:

- Design: Create a 3D model (.STL) of the helical channel using CAD software. Incorporate 500 µm inlet/outlet ports. Crucially, design temporary, thin (<100 µm) support structures connecting the channel to the build plate.

- Print Preparation: Load the resin into the printer vat. Set printing parameters: 405 nm light source, 10 mW/cm² intensity, 2 s exposure per layer (for 10 µm layers).

- Printing: Initiate the layer-by-layer build. The support structures will be co-printed with the channel.

- Post-Processing: a. Carefully transfer the printed part to an IPA bath. Gently agitate for 3 minutes to remove uncured resin. b. Rinse with a second, clean IPA bath for 1 minute. c. Dry using a gentle stream of nitrogen. d. Support Removal: Using fine-tip tweezers under a stereomicroscope, carefully snap away the thin support structures from the main channel. e. Final Cure: Post-cure the device in a UV chamber for 5 minutes to ensure complete polymerization and stability.

- Validation: Connect tubing to the ports, perfuse with dyed water, and inspect for leaks and full channel patency under a microscope.

Protocol B: Fabricating Multi-Layer, Membrane-Integrated Devices via DLP

Objective: To fabricate a two-layer drug-screening device with a porous membrane (20 µm thick) separating a top "gut" channel from a bottom "liver" channel.

Materials & Equipment:

- DLP printer with 385 nm source (e.g., Asiga, Formlabs)

- Clear, rigid resin (e.g., Formlabs Clear V4)

- Sacrificial resin (e.g., High Temp resin or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based)

- IPA and post-curing equipment.

- Compressed air.

Methodology:

- Design: Model three components: i) Bottom liver layer with channels, ii) A thin, perforated membrane layer (pore size: 50 µm), iii) Top gut layer. Design alignment features (e.g., pillars/holes) on all layers.

- Print Layer 1 (Bottom): Print the bottom layer with standard clear resin. Do not post-cure.

- Membrane Integration: In-Situ Method: Carefully remove the bottom layer from the build plate, rinse in IPA, and dry. Place it back in the printer vat, submerged in sacrificial resin. Print the thin membrane layer directly onto the cured bottom layer using the sacrificial resin. Rinse to partially clear the sacrificial resin, leaving the porous structure.

- Print Layer 2 (Top): Place the two-layer part back into the printer, now filled with standard clear resin. Align the print file for the top layer and print it directly onto the membrane-bottom assembly.

- Post-Processing: Wash the fully assembled device in IPA to fully dissolve any remaining sacrificial resin, revealing the porous membrane. Post-cure the entire device for 15 minutes.

- Validation: Perform a diffusion test by flowing a fluorescent dye (e.g., FITC-dextran) in the top channel and measuring its appearance in the bottom channel over time via fluorescence microscopy.

Visualization of Workflows

Title: PµSL Workflow for 3D Helical Channels

Title: Multi-Layer DLP Printing with Sacrificial Membrane

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D Microfluidic Fabrication

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer (PEGDA) | A gold-standard hydrogel precursor for cell-laden devices. Low protein adsorption, tunable stiffness via molecular weight. | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, 700 Da), Sigma-Aldrich |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A highly efficient, water-soluble, and cytocompatible photoinitiator for UV/Violet light crosslinking of hydrogels. | LAP, Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI) |

| Sacrificial/Support Resin | A material printed as temporary support or a soluble interface (like a membrane) that is later removed to reveal hollow channels or pores. | Formlabs High Temp Resin (sol. in IPA), or PVA-based filament for FDM. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA, ≥99.9%) | The standard solvent for washing uncured resin from vat-photopolymerized prints. High purity prevents residue. | Lab-grade IPA, various suppliers |

| Surface Passivation Agent (Pluronic F-127) | A surfactant solution used to coat printed channels to prevent non-specific adsorption of proteins or cells, crucial for biological assays. | Pluronic F-127, Thermo Fisher Scientific |

| Fluorescent Tracers (Dextran Conjugates) | Used to validate channel patency, visualize flow profiles, and quantify diffusion/permeability in fabricated devices. | FITC-Dextran, 70 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich |

Within the broader thesis on 3D printing techniques for rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices, this spotlight focuses on the application of these devices as perfusable, physiologically relevant platforms for tissue engineering. 3D printing, particularly via stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP), enables the rapid, cost-effective fabrication of intricate, biomimetic Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) architectures and integrated porous scaffolds. This accelerates iterative design and validation, moving beyond traditional soft lithography's limitations in speed and geometric complexity.

Key Application Notes

2.1. 3D-Printed Liver-on-a-Chip for Toxicity Screening: Recent studies utilize DLP-printed chips with integrated endothelial and hepatic chamber co-cultures. Metrics include albumin/urea production (hepatocyte function) and release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, cytotoxicity).

2.2. Vascularized Proximal Tubule-on-a-Chip: SLA-printed devices featuring a porous membrane between vascular and epithelial channels model the human kidney filter. Key quantitative endpoints are albumin permeability and glucose reabsorption rates.

2.3. 3D-Bioprinted Scaffolds within Perfusion Chips: Multi-material 3D printing allows for the direct integration of cell-laden, hydrogel-based scaffolds (e.g., GelMA, alginate) into microfluidic channels, creating structured tissue constructs under flow.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Recent 3D-Printed OoC Models

| Organ Model | 3D Printing Technique | Key Functional Metric (Value) | Cytotoxicity Assay (vs. Control) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver-on-a-Chip | DLP | Albumin: 15-20 µg/day/10^6 cells | LDH release: +250% at 10mM toxin | 2023 |

| Kidney Proximal Tubule | SLA | Albumin Reabsorption: 70-75% | Barrier Integrity (TEER): -40% post-nephrotoxin | 2024 |

| Cardiac Microtissue | Inkjet Bioprinting | Contraction Rate: 0.5-1.0 Hz | Viability (Calcein-AM): >85% at Day 7 | 2023 |

| Lung Alveolar Barrier | Multi-jet Printing | Surfactant Protein B: 2.5 ng/mL/day | Pro-inflammatory Cytokine (IL-8): +300% post-challenge | 2024 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a DLP-Printed Liver-on-a-Chip Device for Drug Metabolism Studies Objective: To create a perfusable co-culture chip for evaluating hepatic metabolism and acute toxicity. Materials:

- DLP 3D Printer (e.g., Bison 1000).

- Biocompatible resin (e.g., PEGDA-based, 405nm curing).

- CAD model of chip (channel dimensions: 1000 µm wide x 300 µm high, membrane pore size: 50 µm).

- Primary human hepatocytes & endothelial cells (HUVECs).

- Collagen I solution (for coating). Procedure:

- Printing: Slice CAD file (50 µm layer height). Print using standard biocompatible resin protocol. Post-print, wash in isopropanol (2x 5 min) and UV post-cure (365nm, 15 min).

- Sterilization & Coating: Autoclave (121°C, 20 min). Introduce 0.1 mg/mL Collagen I solution into all channels, incubate (37°C, 2 hrs), rinse with PBS.

- Cell Seeding: Seed HUVECs (2x10^6 cells/mL) into the vascular channel. After 4 hrs attachment, introduce medium at 10 µL/min via syringe pump. Next day, seed hepatocytes (1.5x10^6 cells/mL) into the adjacent parenchymal channel under static conditions for 6 hrs.

- Perfusion & Assay: Initiate co-culture under continuous flow (5-10 µL/min, simulating physiological shear). On day 5 of culture, introduce test compound. Collect effluent daily for albumin (ELISA) and LDH (colorimetric assay) analysis.

Protocol 2: Seeding and Perfusion of a 3D-Bioprinted Scaffold in a Microfluidic Chip Objective: To integrate a 3D cell-laden hydrogel scaffold into a printed chip and maintain it under perfusion. Materials:

- SLA-printed chip with a dedicated scaffold chamber (5mm x 5mm x 1mm).

- GelMA hydrogel (5-10% w/v, methacryloyl degree ~70%).

- Photoinitiator (LAP, 0.25% w/v).

- Cell suspension (e.g., fibroblasts, 10 million cells/mL in PBS). Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation: Mix GelMA and LAP in PBS at 37°C until dissolved. Cool to room temp. Gently mix with cell suspension to final target cell density (e.g., 5x10^6 cells/mL).

- In-Situ Bioprinting/Seeding: Pipette the cell-laden GelMA into the scaffold chamber of the pre-sterilized chip. Expose to 405nm blue light (10 mW/cm²) for 60 seconds through a transparent chip window to crosslink.

- Perfusion Culture: Connect chip to perfusion system with culture medium. Apply a low flow rate (2-5 µL/min) for the first 24 hrs, then increase to 15-30 µL/min. Monitor scaffold contraction and cell viability via live/dead staining at days 1, 3, and 7.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for 3D-Printed OoC Development

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways in a Liver-on-a-Chip Under Toxin Exposure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for OoC & Scaffold Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Brand |

|---|---|---|

| Photopolymerizable Resin (Biocompatible) | Core material for high-resolution 3D printing of microfluidic chips. | BISON UV Resin (Biomedical Grade) |

| Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Hydrogels | Provides a biomimetic 3D scaffold for cell encapsulation and growth (e.g., GelMA, collagen, alginate). | GelMA (Cellink, Advanced BioMatrix) |

| Flow Control System | Precisely controls perfusion of media/compounds through microchannels (syringe pumps, pressure controllers). | Elveflow OB1 Pressure Controller |

| Barrier Integrity Assay Kit | Quantifies endothelial/epithelial monolayer health (e.g., via Trans-Endothelial Electrical Resistance - TEER). | Millicell ERS-2 Voltohmmeter |

| Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit | Dual-fluorescence stain (Calcein-AM/EthD-1) for visualizing live and dead cells in 3D scaffolds. | Thermo Fisher Scientific L3224 |

| Cytokine/Cell Function ELISA Kits | Quantifies organ-specific functional markers (e.g., Albumin for liver, Surfactant Protein for lung). | Human Albumin ELISA Kit (Abcam) |

| Tunable Membrane Inserts (Optional) | For chip designs requiring integrated, porous barriers; can be coated or functionalized. | Transwell inserts (Corning) |

The integration of 3D printing (additive manufacturing) techniques, such as digital light processing (DLP) and stereolithography (SLA), into microfluidic device fabrication has catalyzed a paradigm shift in point-of-care (POC) diagnostic and sensor development. This research directly supports a broader thesis on rapid prototyping by demonstrating how these techniques enable the swift iteration and functionalization of complex, low-cost, and disposable microfluidic platforms for critical POC applications. Key advantages include the rapid creation of devices with integrated features like micromixers, valves, and high-surface-area reaction chambers that are essential for sensitive detection.

Recent advancements facilitated by 3D-printed microfluidics are prominent in several diagnostic domains. The table below summarizes performance metrics from recent (2023-2024) proof-of-concept studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent 3D-Printed POC Microfluidic Devices

| Target/Analyte | Detection Method | 3D Printing Technique | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Assay Time | Key Material | Reference (Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein | Colorimetric (Lateral Flow Readout) | DLP (Resin) | 0.2 ng/mL | 15 min | PEGDA Resin | Anal. Chem. (2024) |

| E. coli O157:H7 | Electrochemical (Impedimetric) | FDM (Conductive PLA) | 10¹ CFU/mL | 30 min | Carbon-black PLA | Biosens. Bioelectron. (2023) |

| Glucose & Lactate | Electrochemical (Amperometric) | SLA (Clear Resin) | 5.2 µM (Glucose) | < 2 min | Enzyme-doped Resin | Sci. Rep. (2023) |

| Cardiac Troponin I (cTnI) | Fluorescence (Sandwich Immunoassay) | Multijet Printing (MJP) | 0.08 ng/mL | 25 min | Acrylic-based Photopolymer | Lab Chip (2024) |

| Dengue Virus NS1 | Colorimetric (Smartphone Densitometry) | SLA (Resin) | 15 ng/mL | 20 min | Commercial Biocompatible Resin | ACS Sens. (2023) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a DLP-Printed Immunoassay Chip for Protein Detection This protocol details the creation of a microfluidic chip with embedded mixing herringbone structures for a colorimetric sandwich ELISA, adapted from recent literature.

I. Device Design & Printing

- Design: Using CAD software (e.g., Fusion 360, SolidWorks), design a chip containing a serpentine incubation channel (500 µm wide x 300 µm high x 10 cm long) with staggered herringbone ridges (50 µm height). Include inlet and outlet ports (1.5 mm diameter). Export as an

.STLfile. - Slicing & Preparation: Import the

.STLfile into the printer's slicing software (e.g., Chitubox for DLP). Orient the chip at a 45° angle to the build platform to minimize layer stress. Set layer height to 25-50 µm. Support structures are automatically generated for overhangs. - Printing: Use a biocompatible, water-clear PEGDA-based resin. Pour resin into the vat. Initiate printing. Post-print, carefully remove the chip from the build plate.

- Post-Processing: Immerse the chip in isopropanol in an ultrasonic bath for 5 minutes to remove uncured resin. Cure under a 405 nm UV lamp for 15 minutes to ensure complete cross-linking and enhance biocompatibility.

II. Surface Functionalization & Assay Protocol

- Surface Activation: Introduce a 1% (v/v) (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) solution in ethanol into the channels. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). Flush with ethanol, then dry under nitrogen.

- Antibody Immobilization: Pump a solution of capture antibody (e.g., anti-cTnI, 10 µg/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) into the channel. Incubate overnight at 4°C. Block with 3% BSA in PBS for 2 hours at RT.

- Sample & Detection: Introduce the sample (e.g., serum spiked with antigen) into the channel. Incubate for 15 min at 37°C with passive mixing via herringbone structures. Wash with PBS-Tween (0.05%).

- Introduce a detection antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (5 µg/mL). Incubate for 10 min at 37°C. Wash thoroughly.

- Signal Generation: Inject the HRP substrate TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine). Allow color development for 3-5 min.

- Readout: Capture an image of the colored channel using a smartphone mounted on a simple dark box. Analyze the mean grayscale intensity using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ). Quantify against a standard curve.

Protocol 2: Development of an FDM-Printed Electrochemical Bacterial Sensor This protocol outlines the creation of a working electrode directly within a microfluidic chip for impedimetric detection of bacteria.

I. Integrated Electrode Printing

- Design: Design a three-electrode system (Working, Counter, Reference) within a flow cell. The working electrode is a serpentine track (1 mm width) leading to a 3 mm diameter sensing pad.

- Printing: Use a dual-extrusion FDM printer. Load the main body filament (e.g., PLA) and conductive filament (Carbon-black doped PLA). Print the chip body first. Pause the print at the layer where electrodes are to be embedded. Swap filament to the conductive material and print the electrode patterns. Resume with the main body filament to seal and complete the chip structure.

- Post-Processing: Polish the exposed electrode surface with fine-grit sandpaper (1200 grit) and rinse with deionized water.

II. Biofunctionalization & Measurement

- Electrode Activation: Cycle the working electrode in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ via cyclic voltammetry (CV) from -0.2 to 1.0 V (vs. pseudo-Ag/AgCl) at 100 mV/s for 20 cycles.

- Probe Immobilization: Apply 10 µL of a solution containing specific bacteriophage or antibody probes (20 µg/mL in PBS) onto the working electrode. Incubate in a humid chamber for 2 hours at RT. Rinse and block with 1% BSA.

- Measurement Setup: Connect the printed electrodes to a portable potentiostat. Flow PBS as the electrolyte at 50 µL/min.

- Impedimetric Detection: Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a frequency range of 10⁵ to 0.1 Hz with a 10 mV amplitude. Record the charge transfer resistance (Rct) in PBS as a baseline.

- Sample Analysis: Introduce the bacterial sample (e.g., E. coli in PBS or diluted food lysate) and incubate under static conditions for 20 min. Wash with PBS. Perform EIS measurement again. The increase in Rct is proportional to bacterial binding on the electrode surface.

Visualization of Workflows

Title: General Workflow for 3D Printed POC Sensors

Title: Colorimetric Immunoassay Protocol on a Chip

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Functionalizing 3D-Printed POC Devices

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photoresins | Base material for SLA/DLP printing; must allow protein adsorption/immobilization. | PEGDA-based resins, Formlabs Biomedical Resin, "WaterShed" mimics. |

| Conductive Filaments | Enable printing of integrated electrodes for electrochemical sensing. | Carbon-black doped PLA, Graphene-doped filaments. |

| Surface Activator (Silane) | Introduces reactive amine (-NH₂) groups onto printed polymer for biomolecule coupling. | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES). |

| Crosslinker | Covalently links activated surface to proteins (e.g., antibodies). | Glutaraldehyde, Sulfo-SMCC. |

| Capture & Detection Probes | Biological recognition elements for specific target binding. | Monoclonal antibodies, aptamers, engineered bacteriophages. |

| Blocking Agent | Reduces non-specific binding on the device surface, lowering background noise. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, or commercial blocking buffers. |

| Enzyme-Label Conjugates | Provide amplifiable signal in colorimetric or chemiluminescent assays. | HRP- or Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP)-conjugated antibodies or streptavidin. |

| Chromogenic Substrate | Produces a visible color change upon enzymatic reaction for simple readout. | TMB (HRP substrate), BCIP/NBT (ALP substrate). |

| Portable Potentiostat | Essential for electrochemical sensor readout; enables field deployment. | PalmSens, EmStat Pico, or ADInstruments devices. |

Context: This application note is framed within a broader thesis on the application of 3D printing techniques for the rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices. It details how these fabricated devices are utilized in high-throughput drug screening and delivery research.

Microfluidic devices, particularly those created via rapid prototyping methods like stereolithography (SLA) and digital light processing (DLP) 3D printing, have revolutionized high-throughput screening (HTS). They enable precise manipulation of fluids at the microliter-to-nanoliter scale, facilitating the creation of biomimetic tissue environments (organs-on-chips) and highly parallelized assay platforms. This significantly reduces reagent consumption, increases assay throughput, and accelerates the drug discovery pipeline from target validation to delivery system testing.

Key Protocols & Experimental Methodologies

Protocol 2.1: 3D Printing and Post-Processing of a Gradient Generator for Compound Screening

This protocol details the fabrication of a microfluidic gradient generator used to test multiple drug concentrations on a single cell-laden device.

Materials:

- 3D Printer: Commercial DLP/SLA printer (e.g., Asiga MAX, Formlabs Form 3).

- Resin: Biocompatible, water-resistant resin (e.g., Dental SG Resin, Formlabs BioMed Clear).

- Software: CAD software (e.g., Autodesk Fusion 360), printer slicer software.

- Post-Processing: Isopropyl alcohol (IPA), compressed air or nitrogen, UV curing chamber.

- Bonding: O2 plasma treater, PDMS, or a compatible adhesive.

Method:

- Design: Create a CAD model of a tree-like or serpentine gradient generator. Channel dimensions: 200 µm (W) x 200 µm (H).

- Print Preparation: Orient the model to minimize supports in fluidic channels. Slice with a layer thickness of 25-50 µm.

- Printing: Initiate print using manufacturer-recommended settings for the selected resin.

- Post-Processing: a. Rinse the printed part vigorously in IPA for 5 minutes to remove uncured resin. b. Dry with clean, compressed air. c. Post-cure in a UV chamber (365 nm) for 20-30 minutes.

- Sealing: Activate the device surface and a flat substrate (glass, PMMA) using O2 plasma (50 W, 1 min). Immediately bring surfaces into contact to form an irreversible seal.

- Quality Control: Perform a leakage test by flowing a colored dye (e.g., food dye in PBS) at 10 µL/min for 10 minutes.

Protocol 2.2: High-Throughput Cell Viability Assay in a 3D-Printed Microarray

Protocol for conducting a drug screen using a 3D-printed device featuring an array of cell culture chambers.

Materials:

- Device: 3D-printed microfluidic array (e.g., 96-unit chamber array).

- Cells: Target cell line (e.g., HepG2 liver cells).

- Reagents: Cell culture medium, trypsin-EDTA, drug library in DMSO, CellTiter-Glo 3D Reagent.

- Equipment: Programmable syringe pump, multichannel pipette, microplate reader.

Method:

- Cell Loading: Prepare a single-cell suspension at 2x10^6 cells/mL. Prime device with medium. Introduce cell suspension into the inlet reservoir, allowing cells to settle into chambers via gravity (30 min). Connect to pump and flow fresh medium at 1 µL/min overnight.

- Drug Treatment: Prepare drug solutions in medium at 10x the final desired concentration. Switch inlet to drug-containing medium reservoirs. Use the pump to perfuse drugs for 48 hours.