Resolving Material Degradation in Biomedical Applications: Strategies for Biomaterials, Drug Delivery, and Implants

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of material degradation in the biomedical field, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Resolving Material Degradation in Biomedical Applications: Strategies for Biomaterials, Drug Delivery, and Implants

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the critical challenge of material degradation in the biomedical field, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental mechanisms behind the breakdown of polymers, metals, and biotherapeutics, and details advanced methodologies for characterizing and leveraging this degradation for drug delivery and tissue engineering. The content further covers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to prevent premature failure, and concludes with a rigorous examination of validation frameworks and comparative forced degradation studies essential for ensuring product safety, efficacy, and regulatory compliance.

Understanding the Fundamentals: Mechanisms and Impacts of Biomaterial Degradation

In the field of biomedical applications, biodegradation is defined as the biological catalytic reaction of reducing complex macromolecules into smaller, less complex molecular structures (by-products) [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this process is crucial for developing implants, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering scaffolds that function safely within the biological environment.

The ideal biodegradable biomaterial must balance structural integrity with controlled breakdown, ensuring that degradation by-products are non-toxic and can be successfully metabolized and eliminated from the body [1]. This technical support center addresses the key experimental challenges and methodological considerations in characterizing and validating biomaterial degradation, providing essential troubleshooting guidance for your research.

Fundamental Concepts: FAQs on Biodegradation Mechanisms

What is the fundamental mechanism of biomaterial biodegradation? Biodegradation occurs through the cleavage of specific chemical functional groups in polymer chains via hydrolytic or enzymatic pathways. Key susceptible functional groups include ester, ether, amide, imide, thioester, and anhydride moieties. The degradation process transforms large polymer molecules into smaller, less complex by-products that can be metabolized or excreted [1].

How does biodegradation differ from simple dissolution? A critical distinction is that biodegradation involves chemical cleavage of molecular chains, while dissolution is merely a physical process where material dissolves without chemical breakdown. This distinction is essential for accurate characterization, as gravimetric analysis (measuring weight loss) alone cannot differentiate between these processes. Confirmatory chemical analysis is necessary to verify true degradation [1].

What are the ideal characteristics of biodegradable materials for biomedical applications? Desirable properties include: (1) no induction of sustained inflammatory or toxic response upon implantation; (2) appropriate shelf-life; (3) degradation time matching the healing or regeneration process; (4) appropriate mechanical properties for the intended application; (5) non-toxic degradation by-products that can be metabolized and cleared; and (6) appropriate permeability and processability [1].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Common Experimental Pitfalls and Solutions

Problem: Gravimetric analysis suggests degradation, but chemical analysis shows no change in molecular structure. Solution: This discrepancy often indicates material dissolution rather than true degradation. Supplement gravimetric measurements with chemical characterization techniques such as FTIR, NMR, or SEC to confirm chemical breakdown. Ensure your degradation medium matches the intended physiological environment (pH, enzyme presence) [1].

Problem: Inconsistent degradation rates between experimental batches. Solution: Batch-to-batch variability is common with natural polymers. Implement strict quality control measures and characterize raw material properties for each batch. Consider synthetic alternatives like PLGA, PLA, or PVA which offer more reproducible degradation profiles [2] [3].

Problem: Difficulty assessing degradation of liquid-based formulations. Solution: Physical degradation assessment approaches like surface erosion monitoring are unsuitable for liquid formulations. Transition to chemical characterization methods including viscosity measurements, molecular weight analysis via SEC, or monitoring of degradation by-products using HPLC or mass spectrometry [1].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Problem: Need for real-time, non-invasive degradation monitoring. Solution: Current ASTM guidelines lack provisions for non-invasive, continuous monitoring. Develop customized methodologies using embedded sensors or optical techniques. Research is focusing on real-time assessment approaches that provide continuous data without sample destruction [1].

Problem: Ensuring biological relevance of in vitro degradation models. Solution: Standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) may not adequately simulate physiological conditions. Incorporate relevant enzymes, adjust pH to match specific tissue environments, and consider mechanical stress factors that mimic in vivo conditions [1] [4].

Standard Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Comprehensive Degradation Assessment Workflow

The following workflow outlines a rigorous approach for biomaterial degradation assessment, integrating physical, chemical, and mechanical evaluation methods:

Detailed Methodological Approaches

Gravimetric Analysis (Mass Loss)

- Protocol: Accurately weigh samples (W₀) before immersion in degradation medium. At predetermined timepoints, remove samples, gently rinse with deionized water, dry to constant weight, and record dry weight (Wₜ). Calculate percentage mass loss as: [(W₀ - Wₜ)/W₀] × 100.

- Troubleshooting: Ensure complete drying without degrading samples. Use controls to account for potential leaching of unbound additives. Remember that mass loss alone cannot confirm degradation [1].

Chemical Structure Analysis via FTIR

- Protocol: Collect FTIR spectra of samples before and during degradation. Focus on changes in characteristic functional group absorptions (e.g., ester C=O stretch at ~1740 cm⁻¹, amide N-H bend at ~1550 cm⁻¹).

- Troubleshooting: Ensure consistent sample preparation and scanning parameters. Look for both disappearance of original bonds and appearance of new degradation products [1].

Molecular Weight Distribution via Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

- Protocol: Dissolve sample aliquots in appropriate solvent (e.g., THF for synthetic polymers). Analyze using SEC system with refractive index detection. Compare molecular weight distributions over time.

- Troubleshooting: Ensure complete dissolution without further degradation. Use appropriate molecular weight standards for calibration [1].

Characterization Techniques: Advantages and Limitations

Comparative Analysis of Degradation Assessment Methods

Table 1: Degradation Assessment Techniques with Applications and Limitations

| Assessment Method | Key Parameters Measured | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric Analysis | Mass loss over time | Simple, cost-effective, quantitative | Cannot distinguish dissolution from degradation; requires drying |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Surface morphology, erosion patterns | Visual evidence of surface changes; high resolution | Destructive; sample preparation may introduce artifacts |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Chemical bond cleavage/formation | Confirms chemical degradation; identifies new functional groups | Limited sensitivity to subtle changes; surface-dominated for ATR-FTIR |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Molecular weight distribution | Tracks backbone cleavage quantitatively | Requires solubility; may not detect crosslinking |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Molecular structure of degradation products | Identifies specific cleavage products; quantitative | Expensive; requires specialized expertise |

| Mechanical Testing | Tensile strength, modulus | Directly measures functional property loss | Destructive; requires multiple samples for time course |

Interconnected Degradation Assessment Approaches

The most accurate degradation assessment comes from integrating multiple complementary techniques, as these approaches are interconnected and provide different perspectives on the degradation process:

Research Reagent Solutions for Degradation Studies

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biodegradation Research

| Material/Category | Examples | Function in Degradation Studies | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Polymers | Chitosan, silk fibroin, alginate, gelatin | Biocompatible, enzymatically degradable substrates | Tissue engineering, drug delivery [2] [5] |

| Synthetic Polymers | PLA, PLGA, PVA, PCL | Controlled degradation via hydrolytic cleavage; reproducible properties | Customizable implants, controlled release systems [2] [3] |

| Degradation Media | PBS, simulated body fluid, enzyme solutions | Simulate physiological environments for in vitro testing | Predictive degradation modeling [1] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Glutaraldehyde, genipin, PEG diacrylate | Control degradation rate through crosslink density | Tunable hydrogel systems [3] [5] |

| Analytical Standards | Molecular weight markers, degradation metabolites | Quantification and identification of degradation products | Method validation and standardization [1] |

Regulatory and Standardization Considerations

ASTM Guidelines and Current Limitations

Current ASTM F1635-11 guidelines specify that degradation should be monitored via:

- Mass loss (measured to 0.1% precision of total sample weight)

- Changes in molar mass (evaluated by solution viscosity or SEC)

- Mechanical testing [1]

However, these guidelines have notable limitations that researchers should address:

- They do not consider invasiveness of degradation approaches that may disturb ongoing degradation processes

- They lack provisions for continuous, real-time assessment

- They provide insufficient guidance for liquid-based formulations [1]

Future Directions in Degradation Assessment

Emerging approaches seek to address current methodological gaps through:

- Non-invasive continuous monitoring techniques that provide real-time data

- Multi-parameter assessment integrating physical, chemical, and biological responses

- Advanced analytical methods including AI-driven degradation prediction and modeling [1] [5]

Successful biodegradation assessment requires a comprehensive, multi-technique approach that confirms chemical degradation beyond simple physical changes. Researchers should:

- Combine gravimetric analysis with chemical characterization to distinguish true degradation from dissolution

- Validate in vitro methods against relevant biological environments

- Address current ASTM limitations through supplementary methodologies

- Consider the interconnected nature of chemical, physical, and mechanical property changes

By adopting these rigorous assessment frameworks, researchers can more accurately predict biomaterial behavior in physiological environments, accelerating the development of safe and effective biodegradable medical devices and implants.

Troubleshooting Guide for Degradation Experiments

Table 1: Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpectedly fast mass loss | Polymer dissolution mistaken for degradation; high solubility of oligomers in media [1]. | Confirm degradation via chemical methods (e.g., SEC, NMR) to track molecular weight reduction, not just mass loss [1]. |

| Inconsistent degradation rates between samples | Lack of control over critical factors like sample thickness, crystallinity, or molecular weight [6]. | Standardize polymer synthesis and processing parameters. Use controls with known degradation profiles for benchmarking [6]. |

| No degradation observed over time | Use of non-reactive degradation media; absence of specific enzymes for natural polymers [7]. | Validate media with control materials. For enzymatic degradation, confirm enzyme activity and accessibility to cleavage sites [7]. |

| High inflammatory response in vivo | Release of acidic or inflammatory by-products (e.g., from PLA or PGA) [6] [8]. | Consider using alternative polymers (e.g., PCL) or modify polymers to buffer pH changes [6]. |

| Mechanical failure before tissue healing | Degradation rate mismatch; mechanical properties decline faster than tissue regeneration [6] [1]. | Select a polymer with slower degradation (e.g., PLA instead of PLGA) or adjust the implant's physical dimensions [6]. |

| Difficulty assessing liquid formulation degradation | Standard physical methods (e.g., gravimetry, SEM) are unsuitable for gels or solutes [1]. | Employ chemical techniques like HPLC, SEC, or NMR to track molecular weight changes and by-product formation directly [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between hydrolytic and enzymatic degradation, and how do I test for each?

A1: The core difference lies in the degradation agent.

- Hydrolytic degradation occurs when water molecules cleave chemical bonds in the polymer backbone, such as ester bonds in PLA or PCL. It is a chemical process [6] [7].

- Enzymatic degradation is a biochemical process where specific enzymes (e.g., esterases, proteases) catalyze the cleavage of polymer chains [7] [1].

To test for each, control the experimental environment:

- For hydrolysis: Use aqueous buffer solutions (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4) and exclude enzymes. Elevated temperature (e.g., 37°C) can accelerate testing [6] [1].

- For enzymatic action: Introduce the relevant purified enzyme into the buffer. Always run a parallel control in buffer alone to differentiate enzymatic effects from simple hydrolysis [7].

Q2: Why is it critical to go beyond gravimetric analysis (mass loss) when assessing biodegradation?

A2: Gravimetric analysis, while simple, can be misleading. A decrease in sample mass might result from polymer dissolving into the media rather than degrading into smaller molecules, or from the loss of non-polymeric additives [1]. True degradation involves the scission of the polymer backbone, which is best confirmed by directly measuring a reduction in molecular weight using techniques like Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) or by identifying chemical by-products with NMR or mass spectrometry [1]. The ASTM guidelines recommend a multi-faceted approach that includes monitoring mass loss, molar mass changes, and mechanical properties [1].

Q3: How do the degradation mechanisms of biodegradable metals, like zinc alloys, differ from those of polymers?

A3: The primary mechanism for metals is corrosion, an electrochemical process, rather than hydrolysis or enzymatic action [8] [9].

- Process: Metallic Zn oxidizes, losing electrons to become Zn²⁺ ions, which then react with water and hydroxides to form corrosion products like zinc oxide and zinc hydroxycarbonate [9].

- Key Factors: The corrosion rate is influenced by the alloy's composition, microstructure, and the local physiological environment (oxygen content, pH, flow conditions) [9].

- Outcome: The metallic implant gradually dissolves, and the corrosion products are metabolized or cleared by the body, providing biofunctions like osteogenesis and antibacterial activity [9].

Q4: How can I control the degradation rate of a polyester-based scaffold for my specific application?

A4: The degradation rate of synthetic polyesters is highly tunable. You can control it through:

- Monomer Selection: Copolymerizing different monomers is highly effective. For example, PLGA degrades faster than PLA or PGA alone, and a 50:50 LA:GA ratio degrades faster than a 75:25 ratio [6].

- Crystallinity: More crystalline regions are generally more resistant to water penetration and degrade slower than amorphous regions [6].

- Molecular Weight: Higher molecular weight polymers typically degrade more slowly due to their longer polymer chains [6].

- Material Geometry: Increasing the surface-area-to-volume ratio (e.g., by creating porous scaffolds) accelerates degradation by allowing greater fluid penetration [6].

Standard Experimental Protocols for Degradation Assessment

Protocol 1: In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation of Polymer Films

This protocol outlines a standard method for tracking the hydrolytic breakdown of solid polymer samples, aligned with ASTM F1635-11 guidelines [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Simulates the ionic strength and pH of the physiological environment [1]. |

| Sodium Azide (0.02% w/v) | Added to PBS to prevent microbial growth that could confound results. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Used to rapidly quench degradation at predetermined time points for analysis. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Solvents | To dissolve polymer samples and determine molecular weight distribution. |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polymer films with precisely documented initial weight (

W0), dimensions, and thickness. Determine the initial molecular weight (Mw_i) via SEC. - Immersion: Immerse pre-weighed samples in PBS buffer (containing 0.02% sodium azide) and incubate at 37°C. Use a high buffer volume-to-sample surface area ratio to maintain sink conditions.

- Sampling: At predetermined time points, remove samples from the buffer, rinse with deionized water, and dry to a constant weight.

- Analysis:

- Gravimetric Analysis: Measure the dry weight (

Wt). Calculate mass loss:((W0 - Wt) / W0) * 100%. - Molecular Weight (SEC): Analyze the dried samples using SEC to track the reduction in molecular weight (

Mw_t) over time. - Morphology (SEM): Image the surface of the dried samples to observe cracks, pores, and surface erosion.

- Gravimetric Analysis: Measure the dry weight (

Protocol 2: Assessing Enzymatic Degradation of a Protein-Based Hydrogel

This protocol is designed for biomaterials susceptible to specific enzymatic cleavage, such as collagen-based scaffolds.

Methodology:

- Hydrogel Formation: Form hydrogels in a standardized format and document their initial mass and storage modulus (

G0). - Enzyme Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of the target enzyme (e.g., Collagenase for collagen) in an appropriate buffer at its optimal pH and temperature.

- Incubation: Immerse the hydrogels in the enzyme solution. Include a control group in buffer without the enzyme.

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: Follow steps 3-4 from Protocol 1 for gravimetric analysis.

- Rheology: Measure the storage modulus (

Gt) of the hydrogels over time to track the loss of mechanical integrity. - By-product Analysis: Use techniques like HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy to quantify the release of specific cleavage products (e.g., amino acids) in the supernatant [1].

Degradation Pathways and Experimental Workflow

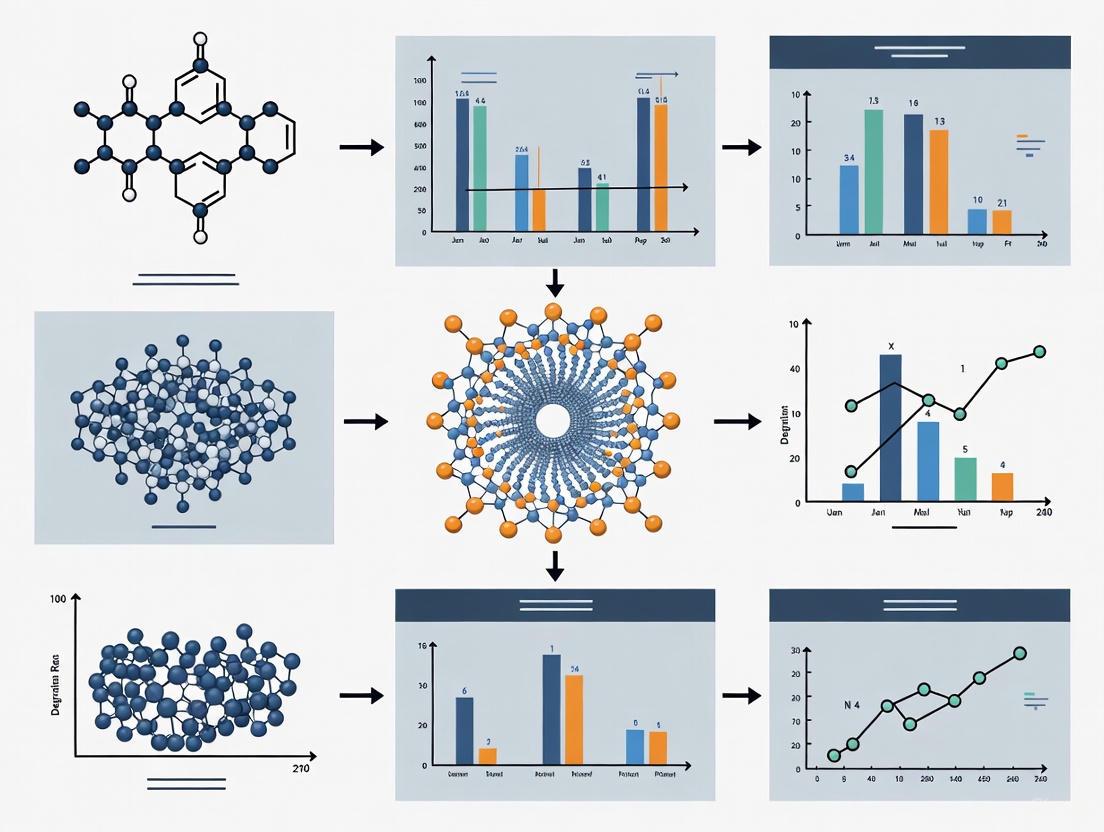

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for assessing biomaterial degradation, highlighting the parallel paths for different mechanisms and the suite of analytical techniques used.

This technical support center provides a focused resource for researchers and scientists navigating the challenges of material degradation in biomedical applications. The following guides and FAQs address common experimental issues with two key material classes: biodegradable polymers and biodegradable metals. Understanding and controlling their degradation profiles is critical for developing effective implants, drug delivery systems, and tissue engineering scaffolds.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Uncontrolled or Unexpected Degradation Rates

Problem: The material (polymer or metal) degrades too quickly or too slowly in in vitro or in vivo environments, compromising its function and biocompatibility.

| Material Class | Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | - Hydrolytic Degradation: Highly sensitive to environmental temperature and humidity. A 50°C increase can accelerate PLA hydrolysis by 30-50% [10].- Enzymatic Degradation: Presence of specific enzymes (e.g., esterases, lipases) rapidly cleaves polymer backbones[cite:7].- Material Crystallinity: High crystalline regions (e.g., in PLA) are more resistant to degradation than amorphous regions[cite:9]. | 1. Characterize the polymer's crystallinity via DSC.2. Measure the pH of the degradation medium; hydrolysis of esters (e.g., in PLA, PCL) can cause acidification[cite:9].3. Test for enzyme activity in the biological medium. | - For too-fast degradation: Increase polymer crystallinity or use polymers with higher glass transition temperatures (Tg)[cite:9].- For too-slow degradation: Incorporate additives like SnCl2 (0.5 wt% can accelerate PLA hydrolysis by ~40%) or copolymerize to reduce crystallinity[cite:7]. |

| Biodegradable Metals | - Alloy Composition & Microstructure: Different phases within an alloy (e.g., in Zn-Mg) can create galvanic couples, accelerating corrosion[cite:3].- Local Environmental Changes: The degradation process itself can alter the local pH and oxygen concentration, changing the corrosion rate[cite:3].- Fluid Dynamics: Static vs. dynamic flow conditions significantly affect ion transport and corrosion product buildup. | 1. Perform metallographic analysis to identify secondary phases.2. Monitor the pH and dissolved oxygen in the immersion medium over time.3. Characterize corrosion products using SEM/EDS and XRD. | - Use high-purity metals to control intermetallic phases.- Employ surface modifications (e.g., coatings) to create a barrier layer initially.- Design alloys with specific elements (e.g., Li for Zn alloys) to form more stable corrosion layers[cite:3]. |

Issue 2: Inadequate Mechanical Performance During Degradation

Problem: The material loses mechanical integrity (e.g., strength, elasticity) too rapidly, failing to provide support for the required healing period.

| Material Class | Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | - Plasticizer Leaching: Additives like glycerol can leach out, causing embrittlement[cite:5].- Molecular Weight Drop: Chain scission from hydrolysis reduces molecular weight and strength long before mass loss is evident[cite:5][cite:7]. | 1. Use Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) to track molecular weight loss over time.2. Perform periodic mechanical testing (tensile, compression) on samples immersed in simulated physiological fluid. | - Blend polymers (e.g., PCL into PLA) to improve toughness and tailor the degradation profile[cite:7].- Use cross-linking agents to create a more stable network and slow strength loss. |

| Biodegradable Metals | - Localized Corrosion: Pitting corrosion creates stress concentrators, leading to premature mechanical failure[cite:3].- Loss of Load-Bearing Cross-Section: General corrosion uniformly reduces the effective cross-sectional area. | 1. Use micro-CT scanning to visualize and quantify internal pitting in 3D.2. Conduct in situ mechanical testing during degradation. | - Design alloys with homogenous microstructures (e.g., fine-grained Zn alloys).- For Zn alloys, adding elements like Li and Mn can significantly increase strength (UTS > 500 MPa) and ductility (up to 108%)[cite:3]. |

Issue 3: Adverse Biological Responses

Problem: The degradation process elicits an undesirable inflammatory response, toxicity, or tissue irritation.

| Material Class | Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodegradable Polymers | - Acidic Degradation Products: Accumulation of acidic monomers (e.g., lactic acid from PLA) can cause local pH drop and inflammatory response[cite:7][cite:9].- Oligomer & Monomer Release: These smaller molecules, often overlooked, can be toxic or act as signaling molecules[cite:9]. | 1. Measure pH change in the local microenvironment.2. Use liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to identify and quantify released oligomers and monomers.3. Perform cell viability assays (e.g., WST-8) with degradation product extracts[cite:2]. | - For acidity: Incorporate buffering agents (e.g., calcium carbonate) into the polymer matrix.- For oligomer toxicity: Modify the polymer with short-chain PEG to enhance histocompatibility[cite:7]. |

| Biodegradable Metals | - Rapid Ion Release: A sudden, high local concentration of metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺) can be cytotoxic[cite:3][cite:4].- Particulate Debris: Metal micro/nano particles from degradation can be phagocytosed, causing inflammation. | 1. Use Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) to track ion release kinetics.2. Analyze tissue sections (histology) for the presence of particulates and immune cell infiltration. | - Control corrosion rate through alloying to ensure a steady, low release of ions (e.g., Zn is essential and has a high tolerance)[cite:3].- Ensure degradation products are biocompatible and participat in natural biological processes (e.g., Zn²⁺ in signaling)[cite:3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key differences in the fundamental degradation mechanisms between biodegradable polymers and metals?

- Biodegradable Polymers primarily degrade via:

- Hydrolysis: Water molecules cleave chemical bonds in the polymer backbone (e.g., ester bonds in PLA, PCL)[cite:7][cite:9].

- Enzymatic Degradation: Specific enzymes (e.g., lipases, esterases) secreted by microorganisms or cells target and break the polymer chains[cite:7].

- Biodegradable Metals degrade primarily through:

- Corrosion: An electrochemical process where the metal oxidizes, losing electrons. In physiological environments, this is often influenced by chlorides, pH, and oxygen content[cite:3][cite:4]. The degradation rate is governed by the composition and the stability of the resulting oxide/hydroxide layers.

FAQ 2: How can I accurately simulate and test for degradation in a physiological environment?

A robust in vitro protocol should consider the following:

- Medium Selection: Use standardized simulated body fluids (SBF), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or more specific media like human duodenal fluid, depending on the target implantation site [11].

- Temperature Control: Maintain a constant 37°C.

- Sterility: Conduct tests under sterile conditions to distinguish abiotic hydrolysis from microbial degradation.

- Dynamic vs. Static: Agitation or flow systems better mimic in vivo conditions than static immersion.

- Monitoring: Key metrics include mass loss, molecular weight loss (for polymers), ion release (for metals, via ICP-MS), pH change, and mechanical property decay.

FAQ 3: We are seeing high variability in our degradation data. What are the primary factors to control?

For consistent results, strictly control these parameters:

- Material Properties: Crystallinity, molecular weight distribution (polymers), grain size and phase distribution (metals), and surface roughness.

- Experimental Conditions: Temperature, pH, buffer concentration, volume-to-surface-area ratio of the sample, and the agitation rate of the immersion medium. Even small deviations can significantly alter degradation kinetics.

FAQ 4: Are "biodegradable" products always safe for biomedical use? What are the hidden risks?

Not necessarily. "Biodegradable" does not automatically mean "biocompatible." Key risks include:

- Toxic By-products: Degradation can release undesirable monomers, oligomers, or metal ions[cite:9]. For example, some BP oligomers are considered an "iceberg" of polymer debris with potential toxicity[cite:9].

- Inflammation from Fragments: Both polymer and metal degradation can generate micro- and nano-scale particles that may provoke an immune response[cite:9].

- Rapid Acidification: Some polymers (like PLA) can create an acidic microenvironment upon degradation, leading to inflammation and tissue damage[cite:7].

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1:In VitroDegradation Testing for Biodegradable Polymers

Objective: To determine the degradation profile of a biodegradable polymer in a simulated physiological environment.

Materials:

- Polymer samples (e.g., films, 3D scaffolds)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4, or other relevant media

- Incubator shaker (37°C, sterile conditions)

- Analytical balance (±0.01 mg)

- Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC) system

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Cut samples to a standard size (e.g., 10x10x1 mm). Record initial dry mass (W₀), dimensions, and characterize initial molecular weight and crystallinity.

- Immersion: Immerse each sample in a sufficient volume of PBS (e.g., 20:1 volume-to-surface area ratio) in sealed containers. Place in an incubator shaker set to 37°C and a low agitation speed.

- Sampling Interval: Remove samples in triplicate at predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 7, 14, 28 days, etc.).

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, dry to constant weight, and measure dry mass (W₁). Calculate mass loss:

(W₀ - W₁)/W₀ * 100%. - Molecular Weight: Use GPC to determine the change in molecular weight and distribution over time.

- Thermal Properties: Use DSC to track changes in glass transition temperature (Tg) and crystallinity.

- Morphology: Use SEM to observe surface erosion, cracking, or pore formation.

- Mass Loss: Rinse retrieved samples with deionized water, dry to constant weight, and measure dry mass (W₁). Calculate mass loss:

Protocol 2:In VitroDegradation Testing for Biodegradable Metals

Objective: To evaluate the corrosion rate and mode of a biodegradable metal sample.

Materials:

- Metal alloy samples (e.g., discs, wires)

- Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) or Hanks' solution

- Incubator (37°C, sterile conditions)

- Analytical balance (±0.01 mg)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

- X-ray Diffractometer (XRD)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Polish samples to a standard surface finish, clean, and sterilize. Record initial dry mass and dimensions.

- Immersion: Immerse samples in SBF at 37°C under sterile, static conditions. Ensure an adequate volume-to-surface area ratio.

- Sampling Interval: Remove samples and collect immersion medium at set intervals.

- Analysis:

- Mass Loss: After removal, clean samples to remove corrosion products according to an ASTM standard (e.g., using chromic acid). Measure the final mass to calculate the corrosion rate.

- Solution Analysis: Use ICP-MS to quantify the concentration of released metal ions (e.g., Zn²⁺, Mg²⁺) in the collected medium.

- Surface Analysis: Use SEM to examine the surface for pitting or uniform corrosion. Use EDS and XRD to identify the chemical composition and phases of corrosion products.

Degradation Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Degradation Mechanism Diagrams

Diagram Title: Fundamental Degradation Pathways for Polymers and Metals

Material Selection and Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Material Selection Workflow Based on Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard isotonic solution for in vitro degradation studies, mimicking salt concentrations in the body. | Maintains pH 7.4; suitable for initial hydrolysis screening but lacks proteins and cells. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | A solution with ion concentrations similar to human blood plasma. | More accurately mimics the in vivo mineral deposition (biomineralization) on materials. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | A widely used synthetic biodegradable polymer. | Degradation rate is highly dependent on crystallinity and molecular weight. Releases acidic by-products [10] [12]. |

| Polycaprolactone (PCL) | A synthetic biodegradable polyester with a low melting point and high elasticity. | Degrades slower than PLA; often blended to modify degradation rates and flexibility [10]. |

| Zn-Li Alloy | A high-strength biodegradable metal for load-bearing applications. | Li significantly strengthens Zn; degradation products can promote osteogenesis for bone implants [9]. |

| Enzymes (Esterases, Lipases) | Used to study enzymatic polymer degradation or simulate inflammatory conditions. | Concentrations and activity units must be standardized for reproducible results [10]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Analyzes thermal transitions (Tg, melting point, crystallinity) of polymers. | Changes in crystallinity during degradation can be tracked, indicating chain scission and reorganization. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Precisely quantifies trace metal ion concentrations in solution. | Essential for measuring metal ion release kinetics from biodegradable metals and composites [9] [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Degradation Kinetics

Q1: Why is my hydrogel degrading too quickly, causing a premature burst release of the drug?

A: Rapid degradation and burst release are frequently caused by:

- Insufficient Crosslinking Density: A low density of crosslinks in the polymer network creates larger pores and faster breakdown. Solution: Increase crosslinker concentration or use a crosslinker with higher functionality. Characterize the new formulation's mesh size and swelling ratio [13].

- High Enzyme Concentration: For enzymatically-degraded hydrogels (e.g., chitosan-based), an unexpectedly high local concentration of enzymes (e.g., lysozyme) can accelerate breakdown. Solution: Incorporate enzyme inhibitors or design the hydrogel with enzyme-cleavable sequences that match the target tissue's specific enzyme profile [14] [15].

- Unexpected Environmental pH: If a hydrogel is designed for pH-sensitive degradation (e.g., in an acidic tumor microenvironment), testing in a different pH can yield invalid results. Solution: Always calibrate your degradation experiments to the precise pH, ionic strength, and enzyme composition of the target physiological environment [14] [16].

Q2: What can cause slow or incomplete degradation, leading to poor tissue integration and potential chronic inflammation?

A: Slow degradation often stems from:

- Excessive Crosslinking: An overly dense network can hinder the diffusion of water, ions, or enzymes needed for degradation. Solution: Optimize crosslinker ratio and explore different crosslinking mechanisms (e.g., physical ionic crosslinking vs. chemical covalent crosslinking) to fine-tune stability [13] [15].

- Material Biostability: Some synthetic polymers (e.g., certain polyesters) have inherently slow hydrolysis rates. Solution: Use copolymers or incorporate rapidly degrading natural polymers like alginate or chitosan to create hybrid systems with tailored degradation profiles [13] [16].

- Lack of Specific Enzymes: If relying on enzymatic degradation, ensure the target tissue expresses the required enzyme at sufficient levels. Solution: Conduct a thorough literature review or preliminary immunohistochemistry to confirm enzyme presence before designing your material [15].

Q3: How do I reconcile the conflicting requirements for mechanical strength and desirable degradation rates?

A: This is a central challenge in biomaterial design. A strong, durable network often degrades slowly.

- Solution: Develop composite or hybrid hydrogels. For example, reinforce a soft, fast-degrading natural polymer (e.g., chitosan) with a synthetic polymer (e.g., PEG) or nanoparticles to enhance mechanical strength without drastically altering the degradation kinetics. The synthetic component can provide structural integrity, while the natural component dictates the degradation rate [14] [16].

- Solution: Utilize hierarchical network structures. Design a dual-crosslinked system where a primary network provides initial strength and a secondary, weaker network controls the drug release profile [13].

Q4: My in vitro degradation data does not match in vivo results. What are the potential reasons?

A: This common discrepancy arises from oversimplified in vitro models.

- Complex In Vivo Milieu: The in vivo environment contains a dynamic mix of cells, enzymes, and mechanical stresses (e.g., fluid flow, tissue compression) not replicated in standard PBS incubation. Solution: Develop more sophisticated in vitro models that include relevant cell cultures (e.g., macrophages), enzyme cocktails, or mechanical stimulation to better predict in vivo performance [13] [16].

- Cellular Activity: Immune cells like macrophages can phagocytose hydrogel fragments, drastically accelerating clearance in a way pure hydrolysis cannot mimic. Solution: Include macrophage co-culture assays in your degradation studies to account for the cellular component of degradation [14].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Degradation Kinetics

Protocol 1: Gravimetric Analysis for Degradation Rate

Purpose: To quantitatively measure the mass loss of a hydrogel sample over time under simulated physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Pre-formed hydrogel samples (e.g., discs or cylinders)

- Degradation buffer (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4, or a specific buffer mimicking the target site like pH 6.5 for tumors)

- Optional: Enzyme solution (e.g., lysozyme for chitosan) in buffer

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.1 mg)

- Incubator/shaker set to 37°C

- Freeze dryer or vacuum oven

Method:

- Initial Mass (W₀): Pre-weigh each dry hydrogel sample (W₀).

- Equilibrium Swelling: Place each sample in a large volume of buffer (to ensure sink conditions) and allow it to swell to equilibrium at 37°C. Record the swollen mass (W_s).

- Degradation Incubation: Transfer the swollen hydrogels to fresh vials containing the degradation buffer (with or without enzymes). Place vials in an incubator at 37°C.

- Mass Monitoring: At predetermined time points, remove samples from the incubation medium. Gently rinse with deionized water to remove ions and buffer salts.

- Drying and Weighing: Lyophilize or vacuum-dry the samples until a constant dry mass (W_t) is achieved.

- Calculation: Calculate the remaining mass percentage at each time point:

- Remaining Mass (%) = (W_t / W₀) × 100

Plot Remaining Mass (%) versus Time to visualize the degradation profile.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Drug Release Kinetics

Purpose: To correlate the degradation of the hydrogel with the release profile of an encapsulated therapeutic agent.

Materials:

- Drug-loaded hydrogel samples

- Release medium (e.g., PBS, often with 0.1% w/v sodium azide to prevent microbial growth)

- Incubator/shaker at 37°C

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer, HPLC, or other suitable analytical instrument for drug quantification

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Immerse each drug-loaded hydrogel in a known volume of release medium.

- Sampling: At scheduled intervals, withdraw a small aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) of the release medium for analysis.

- Replenishment: Immediately replace the withdrawn volume with fresh, pre-warmed release medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in the aliquot using a pre-calibrated standard curve.

- Cumulative Release Calculation:

- Calculate the cumulative amount of drug released at each time point, accounting for dilution from replenishment.

Plot Cumulative Drug Released (%) versus Time on the same graph as the degradation profile (from Protocol 1) to directly visualize the critical link.

Quantitative Data on Hydrogel Degradation and Drug Release

Table 1: Swelling and Degradation Characteristics of Common Biopolymers [15]

| Biopolymer | Typical Swelling Degree (g/g in Water) | Key Degradation Mechanism | Notes on Degradation Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate | 1.65 - 3.85 | Ion exchange (chelators), hydrolysis | Slow hydrolysis; rapid in presence of chelators like citrate. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose | 50 - 200 | Microbial/enzymatic degradation | High swelling can lead to faster enzymatic breakdown. |

| Chitosan | >100% (100% swelling) | Enzymatic (lysozyme) | Degradation rate is highly dependent on deacetylation degree and crystallinity. |

| Starch | 500 - 1200% | Enzymatic (amylase) | Very rapid degradation in the presence of amylase. |

Table 2: Impact of Crosslinking on Hydrogel Properties [13] [14]

| Crosslinking Strategy | Impact on Mechanical Strength | Impact on Degradation Rate | Typical Drug Release Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (Ionic, H-bonding) | Moderate | Fast, often reversible | Can be burst-heavy, sensitive to environmental ions/pH. |

| Chemical (Covalent) | High | Slow, tunable via crosslink density | Sustained, more predictable, often zero-order kinetics. |

| Enzyme-Sensitive Peptides | Variable | Highly specific, triggered | On-demand release upon exposure to specific enzymes. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Degradation and Release Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | A natural polymer forming cationic hydrogels; degrades via lysozyme [14]. | Viscosity and degradation rate depend on molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A synthetic polymer used to create "stealth," tunable hydrogels [16]. | Biocompatible; degradation kinetics can be controlled by using hydrolyzable ester or peptide crosslinkers. |

| Genipin | A natural, low-toxicity crosslinker for polymers like chitosan [14]. | Preferable to glutaraldehyde; creates blue-pigmented hydrogels and slows degradation. |

| Lysozyme | An enzyme used to simulate the enzymatic degradation of chitosan-based hydrogels in vitro [14]. | Concentration should mimic physiological levels found in the target tissue (e.g., serum, tissues). |

| Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) | Enzymes used to create smart, disease-responsive hydrogels that degrade in diseased tissues (e.g., cancer) [16]. | Specific peptide sequences (e.g., cleavable by MMP-2 or MMP-9) must be incorporated into the hydrogel network. |

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Hydrogel Degradation and Drug Release Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Kinetics Study

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My in vitro degradation experiment shows mass loss, but I cannot detect any by-products. What could be wrong with my methodology?

A: Mass loss alone is not a definitive confirmation of degradation, as it could result from the dissolution of soluble material rather than true chemical breakdown [1]. To confirm degradation, you must supplement gravimetric analysis with chemical characterization techniques. We recommend the following protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Place your biomaterial samples (we recommend n=5 per time point for statistical significance) in the appropriate degradation medium (e.g., PBS at 37°C, with or without enzymes like lipase or protease) [1].

- Monitor Mass Loss: Regularly measure mass loss according to ASTM F1635-11 guidelines, ensuring samples are dried to a constant weight with a precision of 0.1% [1].

- Chemical Analysis: Simultaneously, analyze the degradation medium for by-products. Use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to identify and quantify specific chemical monomers like adipic acid, terephthalic acid, or glycolic acid [1] [17]. Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) is recommended for tracking changes in the molecular weight of the polymer itself [1].

Q2: The degradation by-products from my poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) device seem to be altering the local pH, causing unexpected cellular toxicity. How can I investigate this?

A: You are likely observing an autocatalytic effect where acidic by-products lower the local pH, accelerating degradation and causing cytotoxicity [17]. To investigate:

- pH Monitoring: Use a micro-pH probe to track the pH of the degradation medium in real-time throughout your experiment.

- By-product Quantification: Correlate pH changes with the quantified release of acidic monomers like glycolic acid using HPLC [17].

- Validate with Bioassays: Perform standardized bioassays to confirm the toxic effect. The zebrafish embryo model is a sensitive in vivo tool. Expose embryos to your by-products and monitor key endpoints:

Q3: How can I distinguish between hydrolytic and oxidative degradation mechanisms for my PEG-based implant?

A: The primary mechanism can be identified by tailoring the experimental environment and analyzing the chemical outcomes.

- For Hydrolytic Degradation: Conduct aging studies in aqueous buffers at physiological temperature (37°C) and pH (7.4). Hydrolysis will typically cleave ester bonds in polymers like PEGDA or PLA, which you can confirm by using NMR to detect the formation of terminal hydroxyl and carboxylate groups [18].

- For Oxidative Degradation: Expose samples to an oxidizing environment, such as a solution of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). Oxidation often targets ether bonds in polymer backbones, like that of PEG. The shift to a more stable chemistry, such as replacing PEG diacrylate (PEGDA) with PEG diacrylamide (PEGDAA) which resists hydrolysis, can also provide evidence that hydrolysis was the dominant mechanism in the original material [18].

Q4: My biodegradable material is failing in vivo much faster than predicted by in vitro tests. What are the most common reasons for this discrepancy?

A: This is a common challenge, often attributed to the oversimplification of in vitro models. Key factors in vivo that are difficult to fully replicate in vitro include:

- Dynamic Mechanical Loads: In vitro tests are often static, while implants in the body experience stress, strain, and friction, leading to mechanical degradation modes like fatigue and fretting [19].

- Complex Biological Milieu: The in vivo environment contains cells (e.g., macrophages) that release reactive oxygen species and enzymes, leading to oxidative and enzymatic degradation not present in simple buffer solutions [18] [19].

- Protein Adsorption: The adsorption of proteins onto the material surface can trigger an immune response and alter the degradation profile [18].

- In-Service Degradation: The device might be exposed to harsher conditions than anticipated, such as variable pH or chemical exposure [19].

Mitigation Strategy: Implement more advanced in vitro tests that simulate these conditions, such as using bioreactors that apply mechanical strain or incorporating macrophage co-cultures and enzymes into your degradation media [18].

Quantitative Data on Degradation By-Product Toxicity

The table below summarizes toxicity data for common biodegradable plastic monomers, providing a reference for assessing the biological impact of degradation products.

Table 1: Toxicity of Common Biodegradable Plastic Degradation Products in Zebrafish Model

| Degradation Product | Source Polymer | Tested Concentrations | Key Toxicological Endpoints Observed | LC50 (if reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipic Acid | PBAT | Up to 100 mg/L | Inhibition of plant growth (Lycopersicon esculentum, Lactuca sativa) [17] | Fish: 97 mg/L (Pimephales promelas) [17] |

| Terephthalic Acid | PBAT | Not specified in results | Impairment of testicular functions in male Rattus norvegicus [17] | Information missing from search results |

| Glycolic Acid | PGA | 456.3 mg/L | Induction of embryo malformations in Rattus norvegicus [17] | Information missing from search results |

| 1,4-Butanediol | PBAT | Not specified in results | Information missing from search results | Information missing from search results |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Vitro Hydrolytic Degradation of PEG-based Hydrogels

This protocol is adapted from studies on PEGDA hydrogels and can be adapted for other hydrolytically degradable polymers [18].

Objective: To assess the mass loss, swelling behavior, and by-product release of hydrogels under simulated physiological conditions.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- PEGDA Hydrogel: Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate, the primary test material [18].

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4: Standard degradation medium to simulate body fluid [18].

- Lysozyme or other relevant enzymes: To simulate enzyme-mediated degradation [1].

- Liquid Nitrogen: For quickly stopping degradation before analysis.

- Deionized Water: For rinsing samples.

- Lyophilizer (Freeze-dryer): For drying samples to constant mass.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Synthesize hydrogel discs (e.g., 5mm diameter x 2mm thickness) via UV photopolymerization. Determine the initial dry mass (W₀) after lyophilization.

- Degradation Study: Immerse each sample in 10-20 mL of PBS (with or without enzymes) and incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation. Use a minimum of n=5 samples per group for statistical power.

- Sampling and Analysis: At predetermined time points (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14, 28):

- Mass Loss: Remove samples, rinse with deionized water, freeze-dry, and measure dry mass (Wₜ). Calculate mass loss as:

(W₀ - Wₜ)/W₀ × 100%. - Swelling Ratio: After rinsing but before drying, measure the wet mass (Ww). Calculate the mass swelling ratio (Qm) as:

Q_m = W_w / Wₜ. - By-product Analysis: Analyze the degradation medium using HPLC or NMR to quantify the release of PEG fragments, acrylic acid, or other expected monomers [18].

- Mechanical Testing: Periodically measure the compressive or tensile modulus to correlate degradation with functional loss.

- Mass Loss: Remove samples, rinse with deionized water, freeze-dry, and measure dry mass (Wₜ). Calculate mass loss as:

Protocol 2: Assessing By-product Toxicity Using Zebrafish Embryos

This protocol uses zebrafish as a model organism to evaluate the biological effects of degradation products [17].

Objective: To determine the developmental toxicity of degradation by-products like adipic acid, terephthalic acid, and glycolic acid.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Test Compounds: Adipic acid, terephthalic acid, glycolic acid, 1,4-butanediol of high purity [17].

- Zebrafish Embryos: Wild-type (e.g., AB strain), 4-6 hours post-fertilization (hpf).

- Embryo Medium: Standard aqueous medium for raising embryos.

- Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO): For solubilizing compounds, keeping final concentration ≤0.1% [17].

- 3,4-Dichloroaniline (DCA): Use as a positive control for toxicity validation [17].

Methodology:

- Exposure Setup: Dispense 20-30 healthy embryos into 24-well plates, with one embryo per well in 2 mL of embryo medium.

- Dosing: Expose embryos to a range of concentrations of the individual by-products or a mixture. Include a negative control (embryo medium only) and a positive control (e.g., 4 mg/L DCA).

- Incubation and Monitoring: Incubate plates at 28.5°C and monitor endpoints at 96 hpf:

- Survival Rate: Count the number of live versus dead embryos.

- Hatching Rate: Record the number of embryos that have hatched from their chorions.

- Heartbeat Rate: Manually count heartbeats over a 15-second period under a microscope for at least 10 larvae per group.

- Body Length: Measure the standard body length from the head to the tip of the tail using image analysis software.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare results from treatment groups to the negative control using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., one-way ANOVA) to determine significant effects.

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Biomaterial Degradation Assessment Workflow

Diagram 2: Biological Response to Degradation By-products

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Degradation and Toxicity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard aqueous medium for simulating physiological conditions and studying hydrolytic degradation [1] [18]. |

| Specific Enzymes (e.g., Lipase, Protease) | Introduced to degradation media to simulate enzyme-mediated biodegradation pathways relevant to the in vivo environment [1]. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | A widely studied, synthetic hydrogel model system for understanding hydrolytic degradation mechanisms, particularly of ester linkages [18]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | An analytical technique used to separate, identify, and quantify individual degradation by-products (e.g., adipic acid, glycolic acid) in a solution [1] [17]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Spectroscopy used to determine the molecular structure of polymers and their degradation fragments, confirming chemical breakdown [1] [18]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Chromatography method used to monitor changes in the average molecular weight and molecular weight distribution of a polymer as it degrades [1]. |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) Embryos | A vertebrate model organism used for in vivo toxicity screening of degradation products, allowing assessment of developmental endpoints like heartbeat and morphology [17]. |

Methodologies and Applications: Harnessing Degradation for Controlled Release and Regeneration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I achieve a constant, zero-order drug release profile instead of a declining (Fickian) release from my biodegradable polymer device? Achieving zero-order release requires shifting from diffusion-controlled to degradation-controlled release. This can be accomplished by engineering your device's geometry to manage the degradation front. Using vat polymerization 3D printing, you can design structures with specific surface area to volume (SA/V) ratios, strut beam sizes, and pore sizes that modulate the rate of water penetration and acidic byproduct egress. This controls the onset of bulk degradation, which in turn can compensate for the reduction in diffusion-driven release over time, leading to a more constant release profile [20].

Q2: What are the key considerations for selecting a biopolymer for a long-term (e.g., 6-month) implantable drug delivery system? For long-term implants, the material must balance degradation rate with mechanical integrity. Key considerations include:

- Copolymer Ratios: PLGA with a higher lactic acid to glycolic acid ratio (e.g., 75:25) degrades more slowly than 50:50 PLGA, making it suitable for extended release [21].

- Crystallinity: Highly crystalline polymers like pure PGA degrade more predictably but may have slower hydrolysis rates.

- Drug Stability: Ensure the polymer's processing conditions (e.g., melt temperature for spinning) do not degrade the therapeutic agent [21].

Q3: My shape memory polymer (SMP) device is not recovering its shape consistently upon stimulation. What could be wrong? Inconsistent shape recovery can stem from several factors:

- Insufficient or Inhomogeneous Stimulus: For light-triggered SMPs, ensure the photothermal coating (e.g., polydopamine) is uniformly applied and that light intensity is sufficient to heat the entire device above its transition temperature [21].

- Material Issues: Incomplete crosslinking during resin synthesis for 3D printing can lead to a poorly defined polymer network, hindering recovery. Verify your photoinitiator concentration and UV curing time [22] [20].

- Geometric Constraints: The physical environment of the implant site might be restricting the device's movement. Re-evaluate the programmed temporary and permanent shapes for biocompatibility with the anatomical location [22].

Q4: How can I create a device that releases multiple drugs in a specific sequence? Sequential drug release is achievable through multimaterial fiber design. Using a thermal drawing process, you can create a single fiber with multiple, isolated drug reservoirs. Each reservoir is sealed with a biodegradable polymer (e.g., PLGA) with a distinct degradation rate. The polymer with the fastest degradation rate will release its drug first, followed by the next, allowing for pre-programmed, sequential therapy from a single implant [21].

Q5: What sterilization methods are suitable for heat-sensitive biodegradable polymers like PLA and PLGA? Conventional high-temperature methods like autoclaving and gamma radiation can degrade these polymers, causing premature weakening or changes in release kinetics. Suitable alternatives include:

- Low-Temperature Gas Plasma (HPGP) Sterilization

- Ethylene Oxide (EtO) Gas Sterilization [23] Always validate the sterilization method's impact on your specific device's mechanical properties, degradation profile, and drug stability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Burst release followed by very slow release | Poor drug-polymer compatibility; high surface-area-to-volume ratio; microcracks in device. | Optimize drug loading method; reduce surface area or apply a thin, slow-degrading polymer coating; review printing/resin parameters to ensure structural integrity [20] [24]. |

| Premature loss of mechanical strength in vivo | Polymer degradation rate is too fast; acidic degradation byproducts cause autocatalytic erosion. | Switch to a slower-degrading polymer (e.g., higher L-lactide content PLGA or PCL); incorporate buffering agents (e.g., Mg(OH)₂) to neutralize acidic byproducts [25] [23]. |

| Uncontrolled, biphasic/triphasic release profile | Onset of catastrophic bulk degradation. | Redesign device geometry to control water ingress: use 3D printing to create architectures with lower SA/V ratios or smaller pore sizes to delay bulk degradation [20]. |

| Poor cell adhesion or inflammatory response on polymer scaffold | Lack of bioactivity; surface hydrophobicity; cytotoxic impurities. | Modify the surface with bioactive motifs (e.g., RGD peptides); use plasma treatment to increase hydrophilicity; rigorously purify polymers to remove residual catalysts or monomers [25] [26]. |

Table 2: Optimizing 3D Printing for Controlled Release

| Printing Parameter | Impact on Release Profile | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Area to Volume (SA/V) Ratio | Higher SA/V ratios accelerate both drug release and degradation. | For long-term release, design structures with a lower SA/V ratio. For rapid release, use higher SA/V structures like thin meshes [20]. |

| Strut Size / Wall Thickness | Thicker struts delay water penetration, pushing the onset of degradation-controlled release further in time. | Use thicker struts and walls to prolong release duration and achieve more linear release kinetics [20]. |

| Pore Size & Porosity | Larger, interconnected pores increase diffusion rates and can lead to initial burst release. | Utilize smaller, controlled pore sizes to restrict diffusion and place greater control over release in the hands of polymer degradation [20] [27]. |

| Polymer Resin Degradation Rate | Fast-degrading resins lead to quicker onset of degradation-controlled release. | Formulate resins or select polymers with degradation rates that match the desired therapeutic timeframe. Combine fast and slow degrading polymers in a single device [20] [21]. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Engineering Long-Term Controlled Release via Vat Polymerization 3D Printing

This protocol outlines the use of vat polymerization (VP) 3D printing with biodegradable resins to create devices for long-term controlled drug release [20].

1. Resin Formulation:

- Materials: Biodegradable photoreactive polyester resin (e.g., methacrylated PCL-PGA-PTMC triblock), model drug (e.g., Rhodamine B), photoinitiator.

- Procedure: Dissolve the model drug at the desired concentration (e.g., 0.2 wt%) in the liquid resin. Add a compatible photoinitiator. Mix thoroughly using a centrifugal mixer (e.g., 2500 rpm for 1 min, then 3000 rpm for 1 min) to ensure homogeneity and remove air bubbles.

2. Working Curve Analysis:

- Determine the critical exposure energy (Ec) and penetration depth (Dp) of the formulated resin using Jacob's fundamental working curve equation. This calibration is essential for establishing correct printer exposure settings to achieve the desired curing depth and structural fidelity.

3. 3D Printing & Post-Processing:

- Printing: Use a Digital Light Processing (DLP) printer to fabricate the designed geometries (e.g., cylinders, porous cubes). Maintain a constant temperature during printing.

- Washing: Post-print, wash the devices in a suitable solvent (e.g., isopropanol) to remove any uncured resin.

- Post-Curing: Cure the devices under UV light to ensure complete polymerization and maximize mechanical strength.

4. In Vitro Release Study:

- Immerse the drug-loaded devices in a release medium (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4) and maintain at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- At predetermined time points, withdraw aliquots of the release medium and analyze drug concentration using UV-Vis spectroscopy. Replace the medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Plot cumulative release versus time and fit the data to various mathematical models (e.g., Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas) to understand the release mechanism.

Protocol 2: Fabricating Multi-Drug, Sequentially Releasing SMP Fibers via Thermal Drawing

This protocol describes creating multimaterial shape memory polymer fibers (SMPFs) for sequential drug release and light-triggered actuation [21].

1. Preform Fabrication:

- Materials: PDLLA, PLGA with different LA:GA ratios (e.g., 75:25 for slow, 50:50 for fast degradation), photothermal agent (e.g., dopamine hydrochloride), drugs (e.g., Doxorubicin, Curcumin).

- Procedure: Assemble a macroscopic preform by compression molding or machining the constituent polymers. Create hollow channels within the preform using removable PTFE or steel rods to serve as future drug reservoirs. The preform should have a structured cross-section with separate compartments for different drugs.

2. Thermal Drawing:

- Heat the preform in a custom drawing tower to its softening temperature (e.g., 160°C for PDLLA/PLGA). Apply tension to draw the preform into a continuous, microstructured fiber of the desired diameter (e.g., tens of meters long with 10 µm resolution). This process preserves the internal architecture of the preform at a miniaturized scale.

3. Photothermal Coating:

- Immerse the SMPFs in a alkaline dopamine solution (e.g., 2-6 mg/mL in Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) at 40°C for 72 hours. This will result in the self-polymerization of dopamine and the deposition of a uniform polydopamine (PDA) nanoparticle coating on the fiber surface. Rinse with deionized water.

4. Drug Loading and Sealing:

- Prepare drug solutions (e.g., 50 mg/mL in PBS with 0.5% Tween 80).

- Use a vacuum-assisted method to draw the drug solutions into the fiber's hollow channels.

- Seal both ends of the drug-loaded fiber segments with a water-resistant, biocompatible glue (e.g., Araldite Rapid).

5. Characterization:

- Drug Release: Immerse sealed fiber segments in PBS at 37°C. Monitor drug release at intervals via UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Shape Memory Effect: Program the fiber into a temporary shape at elevated temperature, cool, and then trigger recovery using NIR light. Quantify recovery speed and ratio.

- Photothermal Effect: Expose PDA-coated fibers to NIR light and monitor temperature increase with a thermocouple.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Tailoring Polymer Release Profiles

| Material / Reagent | Function / Rationale for Use | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA (Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) | A benchmark biodegradable polyester. Degradation rate (weeks to years) is tuned by varying the LA:GA ratio. | 50:50 PLGA degrades fastest; 75:25 is slower. Acidic degradation products can cause autocatalytic erosion [25] [21]. |

| Methacrylated PCL-PGA-PTMC Triblock Resin | A photoreactive, fast-degrading resin for vat polymerization 3D printing. Allows room-temperature fabrication of complex, high-resolution devices. | Enables study of geometry-degradation-release relationships. Fast degradation allows observation of degradation-controlled release [20]. |

| Polydopamine (PDA) | A photothermal coating. Converts NIR light to heat, enabling remote, precise triggering of shape recovery and accelerated drug release from SMPs. | Coating thickness and density affect photothermal efficiency. Demonstrates good photostability over multiple cycles [21]. |

| Poly(D,L-lactide) (PDLLA) | An amorphous polymer with a distinct glass transition temperature (Tg). Serves as the shape memory matrix in thermally drawn fibers. | Amorphous nature ensures a sharp shape recovery transition. Good compatibility with other polymers like PLGA [21]. |

| Rhodamine B | A fluorescent small-molecule model drug (surrogate). Used for facile, quantitative tracking of release kinetics from prototype devices. | Allows for easy UV-Vis or fluorescence detection without the complexity and cost of handling active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in early R&D [20]. |

| PCL (Poly(ε-caprolactone)) | A slow-degrading, semi-crystalline polyester. Provides extended mechanical support. Often used in blends to modulate the degradation rate of faster-degrading polymers. | Degradation time >2 years. Suitable for long-term implants. Can be methacrylated for VP printing [25] [20]. |

In biomedical applications, controlled degradation is a fundamental property that enables biomaterials to perform their function and then safely break down within the body. This process involves the breakdown of large molecules into smaller, less complex structures (by-products), which can then be metabolized or excreted [1]. For researchers developing microspheres, hydrogels, and nanocomposites, understanding and controlling this process is critical to ensuring material performance, biocompatibility, and therapeutic efficacy.

The ideal degradation profile for a biomaterial is one that matches the healing or regeneration process of the target tissue. Key considerations include the mechanical properties during degradation, the non-toxic nature of the by-products, and the appropriate permeability for the intended application [1]. This technical support guide addresses common fabrication and characterization challenges to help you achieve precise control over your material's degradation behavior.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

This section provides targeted solutions for common experimental issues encountered when fabricating controlled-degradation systems.

General Degradation Challenges

Q1: My biomaterial is degrading too quickly in vitro. What factors should I investigate?

- A: A rapid degradation rate often stems from an imbalance between material composition and the testing environment. Focus on these areas:

- Polymer Selection & Crosslinking Density: Materials with inherently fast hydrolysis rates (e.g., some polyesters) or a low density of crosslinks will degrade more quickly. Consider switching to a more stable polymer (e.g., PLA instead of PGA) or increasing your crosslinking density [28].

- Assessment Technique Error: A common mistake is interpreting simple dissolution as degradation. If your polymer is dissolving in the buffer without chain scission, you will see mass loss that is not true degradation. Confirm degradation by using chemical assessment techniques like SEC or NMR to monitor changes in molecular weight [1].

- Environmental Conditions: Ensure your in vitro degradation medium (e.g., PBS) has the correct pH (typically 7.4) and temperature (37°C). Small deviations can significantly accelerate hydrolysis. If using enzymatic media, verify the enzyme activity and concentration.

Q2: How can I conclusively confirm that my material is degrading, and not just dissolving?

- A: Physical tests like gravimetric analysis (measuring mass loss) can only infer degradation. To confirm it, you must use chemical characterization techniques that detect the breakdown of polymer chains [1]. The table below outlines the key methods.

Table 1: Techniques for Confirming Biomaterial Degradation

| Technique | What It Measures | How It Confirms Degradation |

|---|---|---|

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Molecular weight distribution | A shift to lower molecular weights indicates chain scission. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Chemical structure of polymer and by-products | Appearance of new peaks confirms the formation of degradation by-products. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Mass of molecules in a sample | Identifies the precise mass of small fragments and oligomers formed during degradation. |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Changes in chemical bonds | A change in functional groups (e.g., decrease in ester bonds) indicates hydrolysis. |

Fabrication-Specific Issues

Q3: I am using microfluidics to create hydrogel microspheres (HMs), but I am getting polydisperse particles. How can I improve monodispersity?

- A: Polydispersity in microfluidics is typically related to unstable flow conditions.

- Stabilize Flow Rates: Ensure a stable, pulsation-free flow of both the continuous and dispersed phases using high-precision syringe pumps. Fluctuations in flow rate are a primary cause of size variation.

- Optimize Chip Design & Surface Properties: Use a chip design (e.g., flow-focusing) appropriate for your polymer's viscosity. The channel surface should be properly treated to be wetting for the continuous phase and non-wetting for the dispersed phase to prevent wetting and breakup [29] [30].

- Control Viscosity: The viscosity ratio between the dispersed and continuous phases can significantly affect droplet formation. Aim for a ratio that falls within the stable operating regime for your device geometry.

Q4: The mechanical strength of my nanocomposite hydrogel is insufficient for the target tissue. How can I reinforce it without compromising degradation?

- A: Weak mechanical properties can be addressed by incorporating reinforcing nanomaterials and optimizing the crosslinking network.

- Incorporate Nanomaterials: Add graphene oxide (GO) or other nanoparticles like clays or hydroxyapatite to the polymer matrix. These materials provide mechanical reinforcement through strong interfacial interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking [31] [28].

- Use Dual Cross-Linking: Implement a dual cross-linking strategy. For example, combine ionic crosslinking (which provides toughness) with covalent crosslinking (which provides strength). This creates a synergistic network that is robust yet can still degrade predictably [28].

This section consolidates key quantitative data on materials and assessment methods for easy comparison and experimental planning.

Table 2: Common Biomaterials for Controlled-Degradation Systems: Advantages and Limitations

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages / Degradation Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin (GelMA) | Contains cell-adhesive RGD sequences; good biocompatibility [30]. | Poor thermal stability; low mechanical strength [30]. |

| Alginate | Biocompatible; gentle ionic crosslinking (e.g., with Ca²⁺) [29] [30]. | Excessive swelling can lead to rapid drug release; low cell adhesion [30]. |

| Chitosan | Biocompatible; inherent antibacterial properties [29] [30]. | Poor water solubility at neutral pH; degradation rate is highly pH-sensitive [30]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Excellent water solubility; highly tunable mechanical properties [30]. | Lacks cell adhesion sites; can be susceptible to oxidative degradation in vivo [30]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) in Nanocomposites | High surface area for drug loading; excellent mechanical reinforcement [31]. | Potential long-term cytotoxicity; aggregation in aqueous solutions can occur [31]. |

Table 3: Standardized Methods for Assessing Biomaterial Degradation

| Assessment Parameter | Standard Technique(s) | ASTM Guidelines / Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Loss | Gravimetric Analysis | ASTM F1635-11: Mass loss shall be measured to a precision of 0.1% of total sample weight [1]. |

| Molecular Weight Change | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), Solution Viscosity | ASTM F1635-11: Molar mass shall be evaluated by SEC or solution viscosity [1]. |

| Morphological Change | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Not a direct measure of degradation; used to visualize surface erosion and pore formation [1]. |

| Mechanical Property Change | Tensile/Compression Testing, Rheology | Monitor changes in storage/loss modulus (G'/G") or Young's modulus over time [1]. |

| By-product Identification | NMR, Mass Spectrometry, HPLC | Critical for confirming degradation and assessing by-product toxicity [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabricating Monodisperse GelMA Microspheres via Microfluidics

This protocol describes a method for creating cell-laden or drug-loaded gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) microspheres with a uniform size distribution, a key factor in achieving consistent degradation and release profiles [29] [30].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- GelMA Pre-polymer Solution: GelMA polymer dissolved in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS) at the desired concentration (e.g., 5-15% w/v).

- Photoinitiator: Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) or Irgacure 2959, added to the GelMA solution (e.g., 0.5% w/v).

- Continuous Phase: Surfactant-containing oil (e.g., 2-5% ABIL EM 90 in mineral oil).

- Crosslinking Solution: Calcium chloride solution (for alginate, if used as a composite) or a UV light source (λ = 365-405 nm, for GelMA).

Methodology:

- Microfluidic Device Setup: Prime a hydrophilic microfluidic flow-focusing device with the continuous phase (oil) to fill all channels.

- Droplet Generation: Load the GelMA pre-polymer solution (dispersed phase) into a syringe and pump it into the device at a defined flow rate (e.g., 100-500 μL/hr). Simultaneously, pump the continuous phase at a higher flow rate (e.g., 500-2000 μL/hr) to shear the aqueous stream into monodisperse droplets.

- Collection & Crosslinking: Collect the droplets in a tube. Expose the collected emulsion to UV light (e.g., 5-10 mW/cm² for 30-60 seconds) to photopolymerize the GelMA microspheres.

- Washing: Centrifuge the microspheres and wash several times with PBS or a biocompatible solvent to remove the oil and surfactant.

Diagram 1: Microsphere Fabrication Workflow

Protocol: StandardizedIn VitroDegradation Assessment

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to evaluating the degradation of solid biomaterial formulations, aligned with ASTM guidelines [1].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Degradation Medium: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) or simulated body fluid (SBF). For enzymatic degradation, add the relevant enzyme (e.g., lysozyme, collagenase) at a physiologically relevant concentration.

- Fixation Solution: Glutaraldehyde (e.g., 2.5% in buffer) for SEM sample preparation.

- Solvents for SEC/NMR: Appropriate deuterated solvents or HPLC-grade mobile phases.

Methodology:

- Pre-Degradation Characterization (Day 0): Record the initial dry mass (W₀), dimensions, and mechanical properties of samples (n≥3). Analyze one sample via SEM, FTIR, and SEC to establish the baseline.

- Immersion in Degradation Medium: Place each sample in a separate vial containing a sufficient volume of degradation medium (e.g., 20:1 medium-to-sample volume ratio). Incubate at 37°C under gentle agitation.

- Time-Point Sampling: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1, 7, 14, 28 days), remove samples from the medium.

- Rinse & Dry: Gently rinse samples with deionized water and dry to a constant weight (e.g., under vacuum) for gravimetric analysis.

- Mass Loss Calculation: Calculate the percentage mass loss as:

[(W₀ - Wₜ) / W₀] * 100, where Wₜ is the dry weight at time t.

- Post-Degradation Characterization: Perform SEM on dried samples to observe surface erosion and cracks. Use SEC to determine the change in molecular weight and NMR/FTIR to identify chemical changes and by-products.

Diagram 2: Degradation Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Fabricating Controlled-Degradation Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel polymer; provides cell-adhesive motifs [30]. | Fabrication of microspheres and scaffolds for tissue engineering. |