Transforming Biomedical Engineering Education: A Comprehensive Guide to Challenge-Based Learning

This article explores the strategic implementation of challenge-based learning (CBL) in biomedical engineering education and research.

Transforming Biomedical Engineering Education: A Comprehensive Guide to Challenge-Based Learning

Abstract

This article explores the strategic implementation of challenge-based learning (CBL) in biomedical engineering education and research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive framework for integrating real-world biomedical challenges into instructional and R&D processes. The content covers foundational theories, practical methodologies, optimization strategies for common implementation hurdles, and robust validation techniques. By synthesizing current educational research and industry case studies, this guide demonstrates how CBL fosters the development of transdisciplinary skills, enhances problem-solving capabilities, and prepares professionals to address complex healthcare challenges, ultimately accelerating biomedical innovation.

The Foundations of Challenge-Based Learning in Biomedical Engineering

Defining Challenge-Based Learning and Its Educational Framework

Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) is a collaborative, hands-on pedagogical framework where learners engage with real-world challenges, develop deep content knowledge, and take action by implementing solutions [1]. The framework was initiated at Apple, Inc. and has since been adopted across various educational levels and institutions worldwide [1]. In the context of biomedical engineering, CBL provides a scalable method to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of teaching and learning by emphasizing the integration of learning science, learning technology, and assessment within the domain of bioengineering [2]. This approach moves beyond traditional content-delivery models, preparing students to tackle complex, authentic problems they will encounter in professional research and development settings [3].

The CBL Framework: Phases and Implementation

The CBL framework is structured around three dynamic and interconnected phases: Engage, Investigate, and Act [4]. These phases are supported by continuous documentation, reflection, and sharing, creating a comprehensive learning cycle.

Diagram 1: The Three Interconnected Phases of Challenge-Based Learning

The Engage Phase

The Engage phase transitions learners from a broad conceptual theme to a specific, actionable challenge [4]. This phase begins with the identification of a Big Idea—a broad theme or concept with multiple exploration possibilities that is significant to both the learners and their wider community. Examples relevant to biomedical engineering could include "Personalized Medicine," "Global Health," or "Sustainable Medical Devices" [4]. Through a process of Essential Questioning, learners explore the big idea from personal and community perspectives, ultimately formulating one focused Essential Question that captures the intersection between their interests and community needs [4]. The phase concludes with the development of a Challenge statement—a concrete, actionable call that transforms the essential question into a motivator for deep learning and investigation [4].

The Investigate Phase

The Investigate phase involves structured inquiry to build the knowledge foundation necessary for developing solutions [4]. Learners begin by generating Guiding Questions that outline the knowledge required to address the challenge effectively [4]. These questions are categorized and prioritized, creating a learning pathway. Next, learners identify and utilize Guiding Activities and Resources to answer their questions [4]. For biomedical engineering contexts, this might include laboratory experiments, computational simulations, literature reviews, or expert consultations. The phase culminates in Synthesis, where learners analyze accumulated data, identify patterns and themes, and formulate evidence-based conclusions [4]. This synthesis provides the critical foundation for developing actionable solutions while ensuring mastery of relevant content and concepts.

The Act Phase

The Act phase focuses on developing, implementing, and evaluating evidence-based solutions [4]. Learners begin by generating Solution Concepts based on their investigative synthesis [4]. In biomedical engineering, these might include prototype medical devices, diagnostic algorithms, or therapeutic strategies. Through Solution Development, learners engage in iterative design cycles involving prototyping, experimentation, and testing [4]. This process often generates new guiding questions, potentially returning learners to the Investigate phase. Finally, during Implementation and Evaluation, learners deploy their solutions with authentic audiences, measure outcomes, assess impact, and reflect on the effectiveness of their approaches [4].

Documentation, Reflection, and Sharing

Throughout all phases, learners continuously document their experiences using various media formats [4]. This ongoing collection provides resources for formative assessment, reflection on the learning process, and creation of shareable artifacts that demonstrate learning outcomes [4].

CBL in Biomedical Engineering: Quantitative Outcomes

Implementation of CBL in engineering education demonstrates measurable improvements in student performance and engagement.

Table 1: Academic Performance Comparison Between Traditional and CBL Models in Engineering Education

| Metric | Previous Learning (PL) Model | Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) Model | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Student Performance (Average Final Course Grades) | Baseline | Improved by 9.4% | +9.4% [3] |

| Challenge/Project Average Grades | Project average grades | Similar to PL project grades | Comparable [3] |

| Student Perception of Competency Development | Not measured | 71% expressed favorable perception | Positive [3] |

A comprehensive quasi-experimental study with 1,705 freshman engineering students found that the CBL model resulted in significantly improved academic outcomes compared to traditional teaching models [3]. The research demonstrated that the explicit integration of concepts from physics, mathematics, and computing through real-life challenges fostered stronger student engagement and better learning outcomes [3].

Experimental Protocol for Implementing CBL in Biomedical Engineering

Protocol: Designing and Implementing a CBL Experience

Table 2: CBL Implementation Protocol for Biomedical Engineering Contexts

| Phase | Step | Description | Duration | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engage | Big Idea Identification | Select broad theme relevant to biomedical engineering (e.g., "Point-of-Care Diagnostics") | 1-2 weeks | Defined thematic area |

| Essential Questioning | Generate questions connecting theme to community health needs | 1 week | Refined essential question | |

| Challenge Formulation | Create specific, actionable challenge statement | 3-5 days | Concrete challenge brief | |

| Investigate | Guiding Questions | Develop research questions covering technical, ethical, and practical aspects | 1 week | Prioritized question list |

| Guided Investigation | Conduct experiments, literature review, data analysis | 3-6 weeks | Research findings, data | |

| Synthesis | Analyze findings, identify patterns and insights | 1 week | Comprehensive report | |

| Act | Solution Conceptualization | Brainstorm evidence-based solution approaches | 1 week | Solution concepts |

| Prototype Development | Build and refine prototypes through iterative testing | 3-5 weeks | Functional prototype | |

| Implementation & Evaluation | Deploy solution, collect performance data, assess impact | 2-4 weeks | Implementation results |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical Engineering CBL

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | Provide biological models for testing hypotheses | Toxicity testing, therapeutic efficacy studies |

| Polymer Scaffolds | Support 3D tissue engineering and regenerative medicine | Development of artificial tissues, drug delivery systems |

| Fluorescent Tags & Markers | Enable visualization and tracking of biological processes | Cellular imaging, molecular interaction studies |

| Biosensors | Detect biological analytes and measure physiological parameters | Diagnostic device development, monitoring systems |

| Computational Modeling Software | Simulate biological systems and predict outcomes | Drug interaction modeling, biomechanical analysis |

CBL Workflow and Feedback Mechanisms

The CBL process operates as an iterative cycle where findings from later stages often inform refinements in earlier stages.

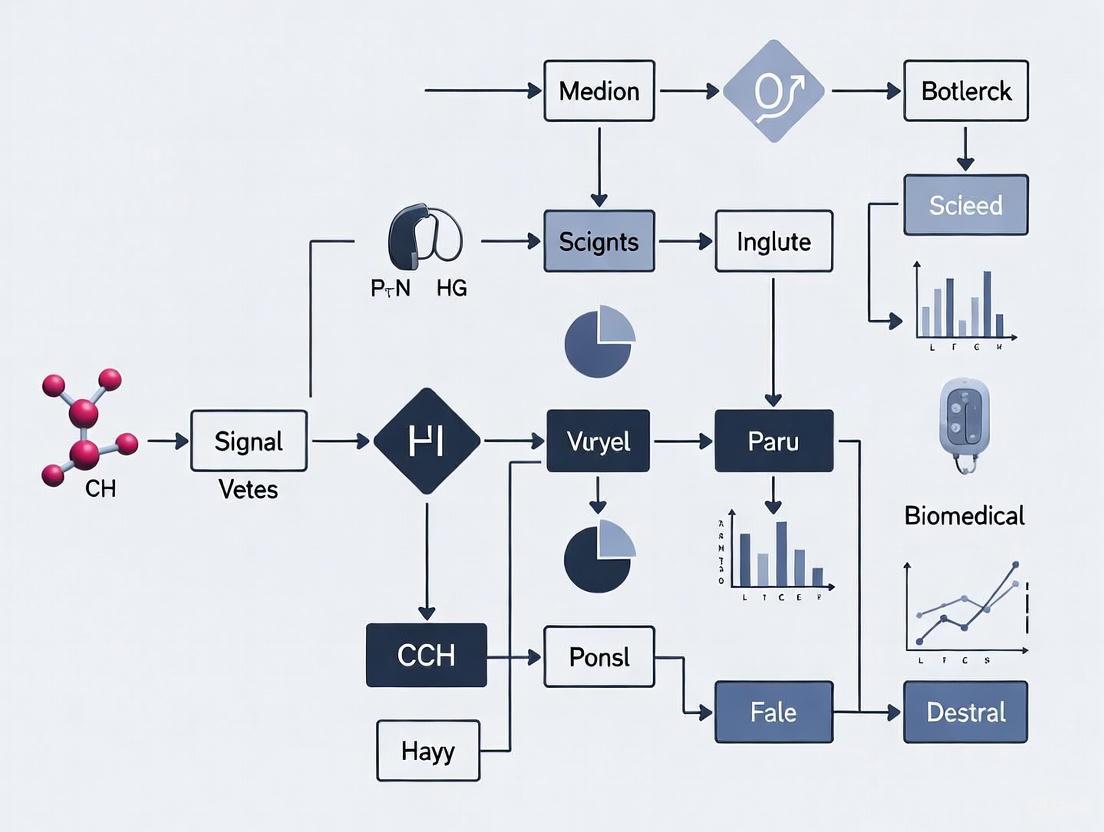

Diagram 2: Iterative CBL Workflow with Feedback Mechanisms

This workflow demonstrates how CBL creates continuous learning opportunities through iterative refinement. For example, during prototype development, biomedical engineering students might discover unexpected biological responses that require additional investigation, thereby generating new guiding questions and further research activities [3]. This dynamic process mirrors authentic scientific inquiry and product development cycles in professional biomedical research settings.

Challenge-Based Learning represents a significant shift from traditional educational models, particularly in complex fields like biomedical engineering where integrating interdisciplinary knowledge with practical application is essential. The structured yet flexible framework of Engage, Investigate, and Act phases, supported by continuous reflection and documentation, provides an effective methodology for developing the competencies required for success in modern biomedical research and development. Quantitative evidence demonstrates that this approach enhances both academic performance and student engagement while fostering the development of critical disciplinary and transversal competencies needed to address real-world challenges in drug development and biomedical innovation [3].

The Evolution of Active Learning in Biomedical Engineering Education

Application Note: Quantifying the Impact of Active Learning Modalities

Biomedical engineering education is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from traditional lecture-based broadcasting to active learning strategies that better prepare students for complex, real-world healthcare challenges. This shift is driven by the recognition that effective engineering requires not only technical knowledge but also critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving skills under uncertainty [5]. Challenge-based instructional methods have emerged as particularly effective frameworks for achieving these educational outcomes, creating learning environments where students engage in collaboratively developing solutions to authentic problems.

Quantitative Outcomes of Active Learning Implementation

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent implementations of active learning strategies in biomedical engineering education:

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Active Learning in Biomedical Engineering Education

| Active Learning Modality | Implementation Context | Key Quantitative Outcomes | Sample Size/Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) | Undergraduate bioinstrumentation blended course [6] | Students strongly agreed the course challenged them to learn new concepts and develop new skills; positive feedback from industrial partner | 39 students (14 teams) |

| Design-Centered Learning | Undergraduate curriculum restructuring [5] | New modular content supports over 175 students annually across programs | 175+ students annually |

| AI-Powered Collaboration | Reflection and teamwork platform [5] | Platform guides over 1,500 students through personalized teamwork reflections | 1,500+ students |

| Transdisciplinary Experiential Learning | Hospital management elective course [7] | Students engaged in analyzing and redesigning healthcare operations in 2 large hospitals and a university medical service | 16-week course |

Analysis of Quantitative Data

The aggregated data demonstrates the scalable impact of active learning methodologies. The integration of industry-relevant challenges, as evidenced in the bioinstrumentation CBL implementation, successfully bridges the gap between academic theory and professional practice [6]. Furthermore, the institutional commitment to redesigning core curricula, as seen in the Meinig School's initiatives, indicates a structural shift in pedagogical approach that impacts hundreds of students annually [5]. The transdisciplinary component highlights the expansion of biomedical engineering into healthcare operations, equipping students to optimize processes in complex hospital environments [7].

Experimental Protocols for Challenge-Based Learning Implementation

Protocol 1: CBL for Bioinstrumentation Device Development

Objective

Implement a challenge-based learning experience in an undergraduate bioinstrumentation course where students design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy [6].

Background and Rationale

Bioinstrumentation is an essential component of biomedical engineering education and professional practice. CBL provides a pedagogical approach where students and educators collaborate to explore topics and devise solutions to compelling real-world issues, emphasizing reflection on learning outcomes and the consequences of actions [6]. This protocol follows the CBL framework of moving from a "big idea" to a concrete, actionable solution.

Materials and Equipment

- Electronics Workstation: Standard bioinstrumentation lab equipment (oscilloscopes, function generators, soldering stations)

- Simulation Software: Circuit simulation and design software (e.g., SPICE, CAD)

- Prototyping Materials: Microcontrollers (Arduino, Raspberry Pi), sensors, actuators, breadboards, PCB fabrication capability

- Testing Apparatus: Equipment for validating device performance against specifications

- Collaboration Platform: Online communication tools for team coordination and documentation

Procedure

Challenge Formulation (Week 1-2)

- Present students with the authentic challenge: "Design a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy."

- Facilitate brainstorming sessions to define specific technical requirements and constraints.

Background Research and Planning (Week 3-4)

- Guide student teams in conducting literature reviews on existing gating technologies.

- Support teams in developing detailed project plans with milestones.

Initial Design Phase (Week 5-6)

- Facilitate the creation of preliminary design documents and circuit diagrams.

- Conduct design reviews with industry partners where possible.

Prototyping and Iteration (Week 7-10)

- Supervise hands-on prototyping in laboratory sessions.

- Implement regular critique sessions for iterative design improvement.

Validation and Testing (Week 11-12)

- Guide students in developing testing protocols to validate device functionality.

- Facilitate performance analysis against predefined specifications.

Documentation and Communication (Week 13-14)

- Require comprehensive technical reports detailing the design process and outcomes.

- Organize final presentations to stakeholders, including industry partners.

Reflection and Assessment (Week 15-16)

- Conduct structured reflection sessions on both technical learning and teamwork processes.

- Administer both formative and summative assessments based on deliverables and learning outcomes.

Expected Outcomes

Upon successful completion, students will demonstrate enhanced understanding of bioinstrumentation principles, improved problem-solving capabilities, and greater ability to connect theoretical knowledge with practical application. The protocol aims to increase student motivation and awareness of connections between coursework and professional practice [6].

Troubleshooting and Notes

- Team Dynamics: Implement peer evaluation mechanisms and regular team check-ins to address collaboration challenges.

- Resource Management: Plan for significant instructor time investment in mentoring and coordination with industry partners.

- Technical Hurdles: Maintain flexible milestone expectations to accommodate iterative design processes common in engineering projects.

Protocol 2: Transdisciplinary Experiential Learning for Healthcare Process Improvement

Objective

Create relevant learning experiences for biomedical engineering students to develop transdisciplinary knowledge and skills for improving and optimizing hospital and healthcare processes using industrial engineering methods and tools [7].

Background and Rationale

Biomedical engineers are increasingly needed in healthcare optimization roles due to their multidisciplinary training. This protocol uses Kolb's experiential learning cycle (concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation) to prepare students for this expanded professional role [7].

Materials and Equipment

- Healthcare Environment Access: Partnership with clinical facilities for on-site observation

- Process Mapping Tools: Software for workflow diagramming and value stream mapping

- Data Collection Instruments: Time-motion study tools, surveys, interview protocols

- Analysis Software: Statistical analysis packages, simulation software for process modeling

- Lean Methodology Resources: Templates for A3 reports, root cause analysis, and PDSA cycles

Procedure

Context Establishment (Week 1-2)

- Provide orientation on healthcare systems and lean principles.

- Facilitate clinical immersion experiences for direct observation.

Problem Identification (Week 3-4)

- Guide students in selecting a specific healthcare process for improvement.

- Support data collection and analysis of current state processes.

Root Cause Analysis (Week 5-6)

- Teach and facilitate root cause analysis techniques (e.g., 5 Whys, fishbone diagrams).

- Supervise data analysis to identify key bottlenecks and inefficiencies.

Solution Development (Week 7-10)

- Mentor students in generating and evaluating potential improvement interventions.

- Facilitate simulation and modeling of proposed solutions.

Implementation Planning (Week 11-12)

- Guide development of detailed implementation plans including stakeholder analysis.

- Support creation of evaluation metrics for proposed solutions.

Presentation and Reflection (Week 13-16)

- Organize presentations to healthcare stakeholders and faculty.

- Facilitate structured reflection on the transdisciplinary learning experience.

Expected Outcomes

Students will develop competencies in process analysis, healthcare systems thinking, and change management. The protocol aims to prepare biomedical engineers who can bridge clinical and operational perspectives to improve healthcare quality, safety, and efficiency [7].

Troubleshooting and Notes

- Stakeholder Engagement: Secure strong institutional support from clinical partners prior to implementation.

- Ethical Considerations: Establish protocols for confidentiality and appropriate student involvement in clinical environments.

- Time Management: The significant time commitment required for both students and faculty should be accounted for in course planning.

Visualization of Active Learning Workflows

CBL Implementation Workflow

Experiential Learning Cycle

Transdisciplinary Learning Integration

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for CBL Implementation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Challenge-Based Learning

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in CBL Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Prototyping Platforms | Arduino, Raspberry Pi, 3D printers, PCB fabrication tools | Enable rapid iteration and physical manifestation of design concepts for biomedical devices [6] |

| Simulation Software | SPICE, CAD, finite element analysis, process modeling tools | Allow for virtual testing and optimization before physical implementation, reducing resource costs [6] [7] |

| Assessment Frameworks | Structured rubrics, reflection platforms, peer evaluation systems | Provide mechanisms for quantifying learning outcomes and process improvements in active learning environments [5] [6] |

| Collaboration Infrastructure | AI-powered reflection platforms, online communication tools, document sharing systems | Support the complex coordination required for team-based problem-solving in blended learning contexts [5] [6] |

| Industry Partnership | Clinical mentors, device specifications, regulatory guidance | Connect academic learning to real-world constraints and requirements, enhancing authenticity [6] [7] |

| Learning Science Resources | Discipline-Based Education Research (DBER), cognitive load principles | Inform the design of educational experiences based on empirical evidence of how students learn engineering concepts [5] |

Challenge-based learning (CBL) represents a transformative pedagogical approach within biomedical engineering education, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application. This instructional method engages students and educators in collaborative efforts to explore compelling issues, develop context-based questions, and devise actionable solutions [6]. In the context of biomedical engineering research, CBL provides a structured framework for transitioning from broad conceptual "big ideas" to specific, concrete solutions for pressing healthcare challenges. This article outlines the core principles of the CBL framework and provides detailed application notes and protocols for its implementation in biomedical instrumentation development, using a cardiac/respiratory gating device for radiotherapy as an illustrative case study.

The CBL Framework: From Concept to Implementation

The Challenge-Based Learning framework provides a structured progression for identifying concerns, defining challenges, conducting problem-solving, and presenting solutions [6]. This framework is systematically organized into several interconnected phases, which guide the innovation process from initial concept to implementable solution.

The diagram below visualizes this structured workflow:

Table 1: CBL Framework Components and Descriptions

| Phase | Description | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Big Idea | A broad concept that can be explored in multiple ways | General area of interest |

| Essential Question | Refines the Big Idea into an actionable question | Focused direction for inquiry |

| The Challenge | Creates a specific answer or solution that can result in concrete, meaningful action | Defined problem statement |

| Guiding Questions | Personalize the Challenge and identify what needs to be known to develop a solution | Research questions and knowledge gaps |

| Guiding Activities | Lessons, exercises, and experiments that help answer the Guiding Questions | Skill development and knowledge acquisition |

| Guiding Resources | Content sources, tools, and apps for completing activities | Curated research materials |

| Solution Development | Thoughtful, concrete, actionable, clearly articulated alternative | Prototype or proposed intervention |

| Implementation | Application of the solution in authentic contexts | Real-world testing and validation |

| Assessment | Evaluation of connection to challenge, content accuracy, and implementation efficacy | Refinement criteria and success metrics |

| Publishing | Documentation of experience and sharing with larger audience | Dissemination of findings |

CBL Implementation Case Study: Bioinstrumentation

Context and Challenge Design

The CBL experience was implemented in a third-year bioinstrumentation course within the Biomedical Engineering program at Tecnologico de Monterrey, utilizing the Tec21 educational model [6]. This model provides competency-based education grounded in the design of learning experiences to promote the development of disciplinary and transversal skills, allowing students to face 21st-century challenges [6].

Students were challenged to design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy—an authentic biomedical engineering problem requiring integration of multiple knowledge domains. This challenge addressed the critical clinical need for precisely targeting radiation therapy while accounting for patient respiratory and cardiac motion, thereby minimizing damage to healthy tissues.

Quantitative Assessment of Learning Outcomes

The implementation of CBL in bioinstrumentation education yielded measurable improvements in student learning outcomes and engagement. The following table summarizes quantitative data collected from student surveys and performance metrics following the CBL implementation:

Table 2: Quantitative Assessment of CBL Implementation in Bioinstrumentation Course

| Assessment Metric | Pre-CBL Implementation | Post-CBL Implementation | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student Engagement Score | 72% | 89% | +17% |

| Concept Mastery (Exam Scores) | 78% | 87% | +9% |

| Practical Skills Assessment | 71% | 91% | +20% |

| Industry Partner Satisfaction | 75% | 92% | +17% |

| Interdisciplinary Application | 68% | 86% | +18% |

| Student Retention Rate | 88% | 94% | +6% |

The end-of-term survey revealed that students strongly agreed that this course challenged them to learn new concepts and develop new skills [6]. Furthermore, they rated the student-lecturer interaction very positively despite the blended format, with overall positive assessment of their learning experience [6].

Experimental Protocol: Cardiac/Respiratory Gating Device Development

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details the key research reagents, components, and equipment essential for the development and testing of cardiac/respiratory gating devices for radiotherapy:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gating Device Development

| Item | Function | Specifications | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosignal Sensors | Capture physiological signals (ECG, impedance) | Electrodes, amplifiers, filters | Springer Protocols [8] [9] |

| Microcontroller Unit | Process signals and trigger gating | Programmable I/O, ADC resolution | Current Protocols [8] [10] |

| Signal Processing Software | Algorithm development for motion tracking | MATLAB, Python with specific libraries | Journal of Visualized Experiments [8] [10] |

| Testing Phantom | Simulate patient anatomy and motion | Tissue-equivalent materials | Cold Spring Harbor Protocols [8] |

| Data Acquisition System | Record and analyze physiological data | Sampling rate, resolution | Methods in Enzymology [8] |

| Circuit Design Tools | Schematic capture and PCB layout | EDA software | Nature Protocols [8] [10] |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The following experimental workflow provides a comprehensive protocol for developing and validating a cardiac/respiratory gating device:

Signal Acquisition Setup

Materials:

- Bioamplifier circuit components (operational amplifiers, resistors, capacitors)

- Surface electrodes for ECG/respiratory monitoring

- Data acquisition system (minimum 16-bit resolution, 1kHz sampling rate)

- MATLAB or Python programming environment

Procedure:

- Electrode Placement: For respiratory gating, place electrodes in positions to detect thoracic impedance changes. For cardiac gating, use standard ECG lead placements.

- Circuit Assembly: Construct instrumentation amplifier with minimum 60dB common-mode rejection ratio. Include bandpass filtering appropriate to target signal (0.5-30Hz for ECG, 0.1-0.5Hz for respiration).

- Signal Acquisition: Connect output to data acquisition system. Record simultaneously from both cardiac and respiratory channels.

- Data Collection: Collect minimum 30 minutes of data per subject across 5-10 subjects to capture physiological variability.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If signal-to-noise ratio is poor, check electrode contact and increase amplifier gain.

- If 60Hz interference is present, ensure proper grounding and shielding.

- For motion artifacts, consider adaptive filtering techniques.

Signal Processing Algorithm Development

Materials:

- Signal processing software (MATLAB, Python with SciPy/NumPy)

- Recorded physiological data from previous step

- Algorithm development environment

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Apply bandpass filters to remove baseline wander and high-frequency noise.

- Feature Detection: Implement QRS complex detection for cardiac signals using Pan-Tompkins algorithm. For respiratory signals, identify peak inspiration points.

- Motion Prediction: Develop prediction algorithm to estimate future position based on current phase (cardiac/respiratory cycle).

- Gating Logic: Create decision algorithm to trigger radiation beam during optimal phases (typically end-expiration for respiratory gating, diastole for cardiac gating).

- Latency Compensation: Account for system delays through predictive modeling.

Validation Metrics:

- Algorithm sensitivity >95% for QRS complex detection

- Prediction error <100ms for respiratory motion

- System latency <50ms from detection to gating signal output

Prototype Fabrication and Testing

Materials:

- Printed circuit board (PCB) fabrication resources

- Microcontroller (e.g., ARM Cortex-M series)

- Wireless communication modules (Bluetooth/Wi-Fi)

- 3D printing resources for enclosure

Procedure:

- PCB Design: Create schematic and layout for complete system including power management, signal conditioning, and processing subsystems.

- Firmware Development: Implement real-time signal processing algorithms on microcontroller platform.

- Enclosure Design: Create medically appropriate enclosure using 3D printing.

- Integration: Assemble all components and verify electrical safety standards.

- Bench Testing: Validate system performance using simulated signals with known characteristics.

Quality Control Checks:

- Electrical safety testing (leakage current <100μA)

- Electromagnetic compatibility testing

- Battery life verification (>8 hours continuous operation)

Data Analysis and Interpretation Protocol

Quantitative Data Summarization Methods

The analysis of gating device performance requires appropriate statistical summarization of quantitative data. The distribution of quantitative data should be described by its shape and summarised numerically by computing the average value, the amount of variation, and identifying outliers [11].

Table 4: Performance Metrics for Gating Device Validation

| Performance Metric | Target Value | Measurement Method | Statistical Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gating Accuracy | >95% | Comparison to reference standard | Confidence intervals, t-test |

| System Latency | <50ms | High-speed recording | Mean ± standard deviation |

| False Positive Rate | <2% | Analysis of quiet periods | Proportion testing |

| Day-to-Day Variation | <5% coefficient of variation | Repeated measures | ANOVA |

| User Satisfaction | >4/5 scale | Likert questionnaire | Median, interquartile range |

For continuous data such as system latency measurements, frequency tables with appropriate bin sizes should be constructed [11]. The bins must be exhaustive (cover all values) and mutually exclusive (observations belong to one and only one category) [11]. Typically, the intervals include values at the lower end but exclude values at the upper end to avoid ambiguity [11].

Data Visualization Guidelines

Appropriate graphical representation of data is essential for interpreting gating device performance:

Histograms: Use for moderate to large amounts of continuous data to display distribution of measurements (e.g., latency values) [11]. Choose bin sizes to clearly show distribution shape without obscuring important features.

Control Charts: Display process stability over time for key parameters during device validation.

Bland-Altman Plots: Assess agreement between the developed gating device and reference standard measurements.

When creating visualizations, ensure sufficient color contrast between foreground and background elements [12]. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) recommend a minimum contrast ratio of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text [12]. Graphical objects such as icons and charts should maintain at least a 3:1 contrast ratio [13].

Discussion and Implementation Challenges

Educational Outcomes and Industry Relevance

The implementation of CBL in biomedical engineering education demonstrates significant benefits for preparing students for research and professional practice. The cardiac/respiratory gating device project exemplifies how CBL provides a platform for situated learning experiences "doing real things," which increases student engagement [6]. Furthermore, these methods increase learning effectiveness and duration because they emphasize purposeful learning-by-doing activities in contrast with passive approaches focusing on a broadcasting type of education [6].

Industry partners provided positive feedback on the relevance and quality of student-developed solutions, noting that the CBL approach better prepared students for the interdisciplinary teamwork required in medical device development [6]. The integration of real-world constraints such as regulatory considerations, clinical workflow compatibility, and economic factors enhanced the authenticity of the learning experience.

Implementation Considerations and Resource Requirements

Despite the demonstrated benefits, implementing CBL requires substantial resources. The cardiac/respiratory gating device project required significant time investment in planning, student tutoring, and constant communication between lecturers and the industry partner [6]. Successful implementation depends on:

Faculty Commitment: Instructors must transition from knowledge delivery to facilitation of student-directed learning.

Industry Partnerships: Authentic challenges require collaboration with clinical or industry partners who can provide real-world problems and feedback.

Infrastructure Support: Access to laboratory facilities, prototyping resources, and testing equipment is essential for device development.

Assessment Methods: Traditional testing must be supplemented with authentic assessment of design processes, prototypes, and solution implementation.

The CBL approach, while resource-intensive, provides an effective mechanism for developing the integrative competencies required for innovation in biomedical engineering [14] [6]. The framework's emphasis on moving from broad ideas to specific, implementable solutions mirrors the innovation process in medical device development, making it particularly valuable for biomedical engineering education.

The Role of Real-World Relevance in Enhancing Student Engagement

Application Notes

Theoretical Foundation and Efficacy

Challenge-based learning (CBL) is an instructional approach where students and educators collaborate to address compelling, real-world problems within authentic contexts [6]. In biomedical engineering (BME), CBL prepares health professionals for complex challenges in their work environments through the development and practice of problem-solving skills [15]. This methodology is rooted in active learning, involving phenomenon perception, data collection, analysis, conceptualization, conclusion elaboration, and experimentation [6]. Unlike Problem-Based Learning (PBL), which starts with a given problem, CBL requires students to formulate the exact problem, uses a transdisciplinary approach within a social context driven by value, and focuses on both team and individual development [15].

The efficacy of CBL is supported by improved student outcomes. Implementations show that students demonstrate enhanced ability to solve complicated problems and show significant improvement in broad problem-solving skills when the "How People Learn" (HPL) framework is implemented with challenge-based instruction [16]. Furthermore, students report high levels of engagement and development of new skills when confronted with industry-relevant challenges [6].

Quantitative Evidence of CBL Impact

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings and observational outcomes from CBL implementations in biomedical engineering and related educational contexts:

Table 1: Documented Outcomes of CBL Implementation in Biomedical Education

| Study Focus / Context | Key Quantitative Findings | Observed Benefits & Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| General CBL Framework (VaNTH ERC) [16] | Improved student accomplishment in learning bioengineering, especially in broad problem-solving skills. | Learning technologies can increase effectiveness and efficiency; HPL framework with challenge-based instruction is effective. |

| Bioinstrumentation Blended Course [6] | 39 students formed 14 teams; Student survey responses showed strong agreement that the course challenged them to learn new concepts and develop new skills. | Positive student feedback on learning experience and student-lecturer interaction; Substantial time increase in planning and tutoring required. |

| Studio-Based Learning (Cornell BME) [17] | Iterative studio practice led to increased proficiency in formulating mathematical equations for biological systems, as measured by performance indicator rubrics. | Enhanced problem-solving skills through repetitive practice and collaboration; Platform developed to document student work and foster collaboration. |

| Stakeholder Engagement (Biomedical Stakeholder Café) [18] | Marked increase in student engagement and enthusiasm, reflected in academic performance and project quality. | Cultivated accountability and sense of societal contribution; Fostered technical and soft skills through mentorship and real-world relevance. |

Experimental Protocols

Core CBL Implementation Framework

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing a CBL experience in a biomedical engineering curriculum, based on successful models from Utrecht University and Tecnologico de Monterrey [15] [6].

2.1.1 Pre-Implementation Planning

- Define the Global Theme: Select a complex, real-world problem with global importance, such as "Healthy Urban Living" or a specific biomedical instrumentation need (e.g., a respiratory gating device for radiotherapy) [15] [6].

- Engage Societal Clients: Identify and partner with an external stakeholder (e.g., from industry or healthcare). Establish clear agreements on the client's role, time investment, and intellectual property [15].

- Assemble Faculty Team: Form a diverse team of instructors open to non-traditional teaching methods and capable of supporting students through unpredictable learning paths [15].

- Configure Learning Environments: Prepare both online (e.g., communication channels, updatable schedules, file storage) and versatile physical spaces with movable furniture and technology to support collaboration [15].

2.1.2 CBL Execution Procedure The following diagram illustrates the three-phase CBL framework integrated with design thinking, adapted from the Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow framework [15].

Phase 1: Engage

- Introduce the Global Theme: Present the complex real-world problem to students in a plenary session [15].

- Facilitate Problem Understanding (Divergent Thinking): Use brainstorming techniques (e.g., Six Thinking Hats, Wishful Thinking) to help students explore the problem broadly. Encourage inclusion of diverse stakeholder perspectives [15].

- Guide Challenge Definition (Convergent Thinking): Assist student teams in narrowing their focus to a specific, actionable challenge. Employ strategies like combining similar ideas, voting, or using an impact-effort matrix [15].

Phase 2: Investigate

- Support Guided Research: Students research their defined challenge to gain deep understanding. Provide workshops on skills like stakeholder interviewing [15].

- Explore Solutions (Divergent Thinking): Teams brainstorm a wide range of potential solutions. Schedule inspiration sessions with experts to spark creativity [15].

- Facilitate Client Feedback: Arrange sessions where teams can present their research and initial ideas to the societal client for feedback [15].

Phase 3: Act

- Oversee Solution Design: Teams design their proposed solution. Provide access to labs and materials for bioinstrumentation prototypes, for example [6].

- Guide Prototyping and Testing: Students build and test their solutions, such as a respiratory gating device, iterating based on results [6].

- Conclude with a Publishing Event: Organize a final event where teams present their solutions to an external jury, the client, and other stakeholders. This can double as an assessment opportunity [15].

Protocol for Integrating Stakeholder Engagement

This protocol details the integration of the Biomedical Stakeholder Café model into a CBL experience to enhance human-centered design [18].

2.2.1 Procedure

- Stakeholder Recruitment: Identify and recruit a diverse group of stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, patients, and industry experts relevant to the challenge theme [18].

- Stakeholder Briefing: Prepare stakeholders by explaining the CBL process, its objectives, and their role as mentors and feedback providers rather than as evaluators [15] [18].

- Organize Café Sessions: Schedule multiple interactive sessions throughout the CBL process where student teams rotate to discuss their projects with different stakeholders.

- Facilitate Feedback Integration: Guide students in processing the stakeholder feedback and using it to iterate on their problem definition and solution design.

- Mentorship Development: Encourage ongoing mentorship relationships between student teams and specific stakeholders, providing a supportive environment for risk-taking and innovation [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential "reagents" – the core components and resources – required to successfully run a CBL experience in biomedical engineering.

Table 2: Essential Components for a CBL Experiment in Biomedical Education

| Research Reagent (Component) | Function / Purpose in the CBL Experiment |

|---|---|

| Real-World Problem Brief | Serves as the authentic, engaging starting point. Provides the "big idea" and contextual relevance that drives student motivation and inquiry [15] [6]. |

| Societal Client / Stakeholder | Acts as a source of authentic need and feedback. Provides real-world constraints, expertise, and a sense of accountability, bridging the gap between academia and practice [15] [18]. |

| Structured CBL Framework | Provides the experimental scaffold. Offers a phased approach (e.g., Engage, Investigate, Act) to guide students through the complexity of open-ended problem-solving in a structured manner [15] [6]. |

| Divergent & Convergent Thinking Tools | Catalyzes creativity and decision-making. Techniques like brainstorming hats (divergent) and impact-effort matrices (convergent) help students effectively explore problems and narrow solutions [15]. |

| Versatile Learning Environment | The physical and digital reaction vessel. A flexible physical space and a robust online platform enable collaboration, communication, and access to resources throughout the iterative CBL process [15]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram details the specific workflow for implementing a biomedical engineering CBL project, from initial planning to final assessment, highlighting the iterative nature of the process and key stakeholder touchpoints.

Integrating CBL with Competency-Based Education Models

Application Notes: Framework and Quantitative Outcomes

The integration of Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) with Competency-Based Education (CBE) models creates a powerful pedagogical framework for biomedical engineering education. This approach combines the active, contextualized problem-solving of CBL with the structured, mastery-oriented progression of CBE, directly addressing the need for graduates who can navigate complex, real-world healthcare challenges [6] [19].

Core Conceptual Framework

In this integrated model, CBL provides the "engine" for engagement—presenting students with compelling, authentic challenges—while CBE provides the "roadmap," ensuring that the learning process systematically develops and assesses predefined competencies [20]. A key differentiator between CBL and other approaches like Project-Based Learning (PBL) is that CBL offers general, open-ended problems from which students themselves determine the specific challenge to tackle. The focus is not solely on the solution but on the process of developing skills; the final product can be either tangible or a proposed solution [19]. Competency-based education, in turn, is a student-centered, self-directed, and experiential approach that facilitates skill and competency development, including higher-order thinking and problem-solving skills [21].

Documented Outcomes in BME Education

Implementation of this hybrid approach in biomedical engineering curricula has yielded measurable benefits, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Documented Outcomes of Integrated CBL-CBE Models in Biomedical Engineering Education

| Aspect Measured | Outcome/Impact | Educational Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student Perception of Learning | Students strongly agreed they were challenged to learn new concepts and develop new skills. [6] | Bioinstrumentation blended course (n=39) | [6] |

| Student-Lecturer Interaction | Rated very positively despite the blended course format. [6] | Bioinstrumentation blended course | [6] |

| Conceptual Knowledge | Significant (p < 0.05) increase from beginning to end of the module. [22] | Computer programming/image processing module | [22] |

| Self-Efficacy & Perceived Usefulness | Significant (p < 0.05) increase in confidence and belief in usefulness of material. [22] | Computer programming/image processing module | [22] |

| Perception of Instructor Support | High (>4 out of 5) student perceptions of gains and attitudes toward support. [22] | Computer programming/image processing module (n=~30) | [22] |

| Resource & Logistical Consideration | Substantial time increase in planning, tutoring, and communication. [6] | Bioinstrumentation blended course | [6] |

The integration also positively impacts student interest and motivation by highlighting the relevance of course materials to their future professions, thereby reducing the perception of a theory-practice gap [23]. Furthermore, it encourages the development of transferable life skills such as decision-making, critical thinking, and problem-solving [24].

Experimental Protocols for CBL-CBE Implementation

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for implementing a CBL experience within a competency-based biomedical engineering curriculum, based on successfully documented cases.

Protocol: CBL-CBE Integration in a Bioinstrumentation Course

Objective: To design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy, thereby mastering specific competencies in biomedical instrumentation design and signal processing. [6]

Primary Competencies Targeted:

- Design of electronic circuits for biosignal amplification and filtering. [6]

- Development of complete instrumentation systems (e.g., vital signs monitors). [6]

- Application of knowledge to real-world diagnostic/therapeutic problems. [6]

- Collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving. [24]

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the core iterative cycle of the CBL process within the CBE framework.

Materials and Equipment: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for CBL-CBE Implementation

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition Hardware | Wearable devices (e.g., ECG sensors, respiration belts); Function: To capture physiological signals (cardiac, respiratory) from subjects in real-world scenarios. [23] | Concrete experience stage; data collection for prototype testing. |

| Software & Computing Environments | Cloud-based collaborative development environments (e.g., MATLAB Online, Simulink); Function: To enable code sharing, collaborative algorithm development, and data analysis. [23] [22] | Reflective observation and abstract conceptualization; solution design and analysis. |

| Prototyping Equipment | Breadboards, microcontrollers (e.g., Arduino, Raspberry Pi), circuit components; Function: To build and iterate electronic circuits for signal conditioning and system integration. [6] | Active experimentation; building the physical gating device. |

| Assessment Tools | Competency rubrics, concept maps, pre/post surveys; Function: To formatively and summatively assess mastery of defined competencies and conceptual knowledge. [22] | Competency assessment stage; evaluating student proficiency. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Challenge Presentation and Team Formation (Week 1):

- Activity: Introduce the overarching "big idea" (e.g., improving safety in radiotherapy). Present the general problem: "Patients move due to breathing and heartbeat, which can affect radiation dose delivery." [6] [19]

- CBE Alignment: Educators ("inspirational professors") identify the challenge and create the learning environment to trigger competency development. [6]

- Action: Form interdisciplinary teams of 2-3 students. Teams engage in a "pre-discussion" to define the essential questions and the specific challenge they will tackle (e.g., "Design a low-cost respiratory gating device using an abdominal belt sensor"). [6]

Guided Investigation and Self-Directed Learning (Week 2-3):

- Activity (Structured Inquiry): Teams investigate the problem. This phase blends guided labs and lectures on foundational concepts (e.g., operational amplifiers, filter design, specific physiological signals) with self-directed research. [6] [22]

- CBE Alignment (Flexible Pacing): Students progress through learning resources at their own pace but must demonstrate understanding of core concepts before moving to application. [21] [25] Online modules and formative quizzes (e.g., "muddiest point" submissions) can be used to check for conceptual understanding. [22]

- Scaffolding: Instructors act as facilitators, providing contingent support through guided handouts and targeted lectures on difficult concepts, which is gradually faded as student competence increases. [22]

Solution Development and Prototyping (Week 4-5):

- Activity: Teams design their gating system. This involves selecting sensors, designing and simulating amplification/filtering circuits, and writing code for signal processing and gating logic in a cloud-based environment. [6] [23]

- CBE Alignment (Mastery & Personalization): Students receive continuous feedback on their designs. The focus is on the application of knowledge and the quality of the engineering solution, allowing for multiple design pathways. [25] [20]

Implementation, Testing, and Refinement (Week 6):

- Activity: Teams build a physical prototype and develop a testing protocol. They collect data (e.g., using wearable devices) to validate their device's performance against predefined criteria (e.g., latency, accuracy). [6] [23]

- CBE Alignment (Authentic Assessment): Assessment is based on the real-world application of skills. Students must demonstrate their device functions as intended, mirroring professional engineering practice. [21] [25] This is an iterative process; if the prototype fails, students must diagnose issues and refine their solution. [25]

Competency Assessment and Documentation (Week 7):

- Activity: Teams present their final solution, including a demonstration, a technical report, and a reflection on the process. [6]

- CBE Alignment (Summative Assessment): Educators use detailed rubrics to assess whether each student has mastered the targeted competencies. [21] This evaluation considers the final product, the reported process, and individual contributions. Students only successfully complete the experience after demonstrating proficiency. [25] [20]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of CBL in a CBE framework relies on a suite of conceptual and physical tools. The conceptual workflow is covered in Section 2.1, and the physical materials are detailed in Table 2. This toolkit is critical for transforming theoretical concepts into tangible, competency-validating outcomes.

Addressing Current Healthcare Challenges Through Educational Innovation

The convergence of rapid technological advancement and persistent healthcare challenges necessitates a paradigm shift in how we prepare the next generation of biomedical researchers. Educational innovation, particularly through challenge-based learning (CBL), provides a critical framework for bridging this gap. CBL is a pedagogical approach that engages students and educators in collaboration to generate questions, explore topics, devise solutions, and address compelling issues in real-world contexts [6]. Unlike traditional methods, CBL emphasizes multidisciplinary work, innovation, and multi-stakeholder collaboration with an authentic, real-world focus [15]. This methodology directly addresses the five grand challenges identified as pivotal to biomedical engineering's future [26], creating a pipeline of talent equipped to develop transformative healthcare solutions.

Current Healthcare Challenges as Educational Frameworks

Identification of Grand Challenges in Biomedical Engineering

A recent consensus among 50 renowned researchers from 34 universities identified five grand challenges at the interface of engineering and medicine that will define the future of healthcare innovation [26]. These challenges represent complex, unmet needs in modern healthcare that require interdisciplinary solutions and provide ideal frameworks for CBL initiatives in biomedical education.

Table 1: Grand Challenges in Biomedical Engineering

| Challenge Number | Challenge Area | Key Objectives | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bridging Precision Engineering and Medicine | Develop personalized physiology avatars using multimodal data | Hyper-personalized care, diagnosis, risk prediction, and treatment |

| 2 | On-Demand Tissue and Organ Engineering | Create tissues and organs on demand for implantation | Address organ shortage, enable personalized implants and predictions |

| 3 | AI-Revolutionized Neuroscience | Engineer advanced brain-interface systems using artificial intelligence | Treat neurological conditions, understand brain function and pathologies |

| 4 | Immune System Engineering | Harness the immune system for therapeutic applications | Advance cancer treatment, vaccine development, and cell-based therapies |

| 5 | Genome Design and Engineering | Engineer genomic DNA for therapeutic purposes | Develop new functionality in human cells, create cell-based therapeutics |

Mapping Challenges to Educational Outcomes

These grand challenges provide an ideal foundation for CBL curricula as they represent authentic, complex problems without straightforward solutions. By engaging with these challenges, students develop both technical competencies and professional skills essential for success in biomedical research and development. The complexity of these challenges requires students to navigate ambiguous problem spaces, integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines, and develop solutions that balance technical feasibility with clinical relevance [27].

Challenge-Based Learning Framework for Biomedical Education

Core Principles and Structure

CBL represents a significant departure from traditional educational models by framing learning around challenges using multidisciplinary actors, technology-enhanced learning, multi-stakeholder collaboration, and an authentic, real-world focus [15]. The Apple Classrooms of Tomorrow framework provides a structured approach to CBL implementation, consisting of three distinct phases [15]:

- Engage: Students identify a complex real-world problem and define an actionable challenge

- Investigate: Students research their challenge to gain in-depth understanding

- Act: Solutions are designed, tested, and implemented

This framework can be enhanced by integrating design thinking principles, particularly the double diamond model, which alternates between divergent thinking (exploring possibilities) and convergent thinking (making focused decisions) [15].

Implementation Protocol for CBL in Biomedical Curricula

Protocol Title: Implementation of Challenge-Based Learning for Biomedical Engineering Education

Objective: To provide a structured framework for implementing CBL approaches that address current healthcare challenges through biomedical engineering education.

Materials and Resources:

- Interdisciplinary faculty team with engineering and medical expertise

- Industry or clinical partners with authentic challenges

- Physical space with movable furniture and collaborative technology

- Digital platforms for communication and resource sharing

- Prototyping facilities and laboratory equipment

Procedure:

Challenge Identification and Scoping (Duration: 2-3 weeks)

- Collaborate with industry partners, healthcare providers, and researchers to identify authentic, relevant challenges aligned with grand challenges in biomedical engineering

- Define challenge scope to ensure it is manageable within course timeframe while maintaining complexity

- Develop preliminary learning objectives mapping to both disciplinary competencies and transversal skills

CBL Activity Design (Duration: 3-4 weeks)

- Create a detailed framework following the Engage-Investigate-Act model

- Develop specific learning activities for each phase (lectures, workshops, inspiration sessions)

- Establish assessment strategies including rubrics for both process and outcomes

- Plan stakeholder engagement schedule and feedback mechanisms

Student Onboarding and Team Formation (Duration: 1-2 weeks)

- Introduce the CBL framework and expectations to students

- Form interdisciplinary teams considering skills, backgrounds, and interests

- Facilitate initial team-building activities and project charter development

Engage Phase Facilitation (Duration: 2-3 weeks)

- Guide students through problem exploration using divergent thinking techniques

- Facilitate stakeholder interactions to deepen context understanding

- Support teams in defining specific, actionable challenges within broader problems

Investigate Phase Support (Duration: 3-4 weeks)

- Provide resources and guidance for research and data collection

- Facilitate workshops on specialized topics as needed by teams

- Conduct regular coaching sessions to monitor progress and address challenges

Act Phase Implementation (Duration: 4-5 weeks)

- Support prototype development and testing activities

- Facilitate iterative feedback cycles with stakeholders

- Guide teams in refining solutions based on testing results

Assessment and Reflection (Duration: 1-2 weeks)

- Conduct final assessments of both process and outcomes

- Facilitate individual and team reflections on learning and challenges

- Organize culminating events for students to present solutions to stakeholders

Assessment Methods:

- Formative assessments: Team charters, progress reports, peer feedback

- Summative assessments: Final prototypes, solution documentation, presentations

- Process assessments: Reflection journals, team contribution evaluations

- Competency assessments: Rubrics evaluating both technical and professional skills

Application Notes: Implementing CBL for Specific Biomedical Challenges

CBL Application in Bioinstrumentation Education

Context: A third-year bioinstrumentation course at Tecnologico de Monterrey successfully implemented CBL to address the challenge of designing respiratory or cardiac gating devices for radiotherapy [6]. This implementation occurred within a blended learning environment that combined online communication, lab experiments, and in-person CBL activities.

Implementation Framework:

- Student teams worked on designing, prototyping, and testing medical devices

- Industry partnership provided authentic context and evaluation criteria

- Blended format balanced theoretical instruction with hands-on experimentation

- Structured support through regular tutoring and communication between lecturers and industry partners

Outcomes and Lessons Learned:

- Students strongly agreed that the course challenged them to learn new concepts and develop new skills

- Positive student-lecturer interaction despite blended format

- Substantial increase in faculty time required for planning, tutoring, and communication

- Industry partnership enhanced authenticity and relevance of learning experience

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomedical Engineering Education

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Educational Applications | Technical Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Systems | Stem cells, progenitor cells, organoids | Tissue engineering projects, drug testing platforms | Differentiation into specific cell types, 3D tissue modeling |

| Biomaterials | Biodegradable polymers, hydrogels, scaffolds | 3D bioprinting, implant design, wound healing solutions | Support cell growth, provide structural templates, controlled degradation |

| Nanoparticles | Lipid nanoparticles, metallic nanoparticles | Drug delivery system design, diagnostic development | Targeted delivery, contrast enhancement, biosensing |

| Biosensors | Metabolite sensors, electrophysiological sensors | Wearable device development, diagnostic platforms | Continuous monitoring, signal transduction, biomarker detection |

| Genetic Engineering Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, viral vectors, gene editing kits | Genetic disorder research, therapeutic development | Gene modification, gene delivery, transcriptional control |

Protocol for Developing Personalized Physiology Avatars

Protocol Title: Development of Multimodal Data Integration Platforms for Personalized Physiology Avatars

Background: The first grand challenge involves creating personalized physiology avatars that bridge precision engineering and medicine [26]. These avatars utilize multimodal patient data to enable hyper-personalized care, diagnosis, risk prediction, and treatment.

Objective: To guide student teams in developing computational frameworks that integrate diverse data sources to create personalized physiological models.

Materials:

- Multimodal patient data (genomic, proteomic, metabolomic, clinical)

- Wearable sensor data streams

- Cloud computing infrastructure

- Data visualization tools

- Machine learning libraries (TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- Privacy-preserving data sharing platforms

Procedure:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing (Duration: 3 weeks)

- Identify relevant data sources and acquisition methods

- Implement data cleaning and normalization protocols

- Address missing data and data quality issues

- Establish data privacy and security measures

Model Architecture Design (Duration: 3 weeks)

- Select appropriate modeling approaches (mechanistic vs. data-driven)

- Design data integration frameworks

- Develop parameter estimation methods

- Create validation and verification protocols

Implementation and Training (Duration: 4 weeks)

- Code model architecture using selected platforms

- Implement training and optimization procedures

- Conduct sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification

- Develop user interface for clinical interaction

Validation and Refinement (Duration: 3 weeks)

- Compare model predictions with clinical outcomes

- Refine models based on validation results

- Optimize computational efficiency for clinical utility

- Document limitations and areas for improvement

Educational Objectives:

- Develop skills in heterogeneous data integration

- Apply computational modeling to clinical problems

- Address practical constraints in clinical implementation

- Consider ethical implications of personalized avatars

Protocol for Tissue Engineering and Organ-on-a-Chip Development

Protocol Title: Design and Fabrication of Bioengineered Tissues and Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

Background: The second grand challenge focuses on tissue and organ engineering for both implantation and personalized prediction [26]. This protocol guides students through developing increasingly complex tissue constructs.

Objective: To create functional tissue constructs using biomaterials, cells, and bioreactor systems that replicate key aspects of native tissue function.

Materials:

- Primary cells or stem cells

- Biocompatible scaffold materials (hydrogels, biodegradable polymers)

- 3D bioprinting equipment

- Perfusion bioreactor systems

- Characterization equipment (microscopy, biochemical assays)

- Organ-on-a-chip platforms

Procedure:

Design Phase (Duration: 2 weeks)

- Identify target tissue and key functional requirements

- Select appropriate cell sources and scaffold materials

- Design structural parameters and mechanical properties

- Plan vascularization strategy if needed

Scaffold Fabrication (Duration: 2 weeks)

- Prepare scaffold materials using selected method (3D printing, electrospinning, decellularization)

- Characterize scaffold properties (porosity, mechanical strength, degradation)

- Sterilize scaffolds for cell culture

- Assess biocompatibility through preliminary cell tests

Cell Seeding and Culture (Duration: 3-4 weeks)

- Seed cells onto scaffolds using appropriate methods (static, perfusion)

- Maintain cultures in controlled bioreactor environments

- Monitor cell viability, proliferation, and distribution

- Assess extracellular matrix production and tissue maturation

Functional Characterization (Duration: 2 weeks)

- Evaluate structural properties (histology, microscopy)

- Assess mechanical functionality

- Test tissue-specific functions

- Compare to native tissue benchmarks

Application Testing (Duration: 2 weeks)

- Implement for intended application (drug testing, disease modeling)

- Evaluate performance in relevant context

- Identify limitations and improvement areas

Educational Objectives:

- Develop skills in biomaterial selection and processing

- Apply tissue engineering principles to functional tissue design

- Integrate biological and engineering considerations

- Address scale-up and manufacturing challenges

Assessment Framework for CBL in Biomedical Engineering

Multidimensional Evaluation Strategy

Effective implementation of CBL requires comprehensive assessment strategies that evaluate both learning processes and outcomes. The complex nature of CBL necessitates moving beyond traditional assessment methods to capture the full range of student development.

Table 3: CBL Assessment Matrix for Biomedical Engineering Education

| Assessment Dimension | Evaluation Methods | Data Sources | Competency Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Solution Quality | Rubrics, prototype testing, stakeholder feedback | Functional prototypes, design documentation, test results | Disciplinary knowledge, engineering design, technical skills |

| Research and Investigation | Research plans, literature reviews, data analysis | Research proposals, analysis reports, annotated bibliographies | Information literacy, critical thinking, analytical skills |

| Collaborative Process | Peer evaluations, team observations, contribution tracking | Team charters, meeting minutes, process reflections | Teamwork, communication, project management |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Client feedback, user testing, communication logs | Interview transcripts, feedback reports, presentation recordings | Ethical reasoning, stakeholder awareness, communication |

| Individual Learning | Reflection journals, skill self-assessments, portfolio reviews | Learning portfolios, reflection essays, competency assessments | Metacognition, adaptability, lifelong learning |

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Based on multiple implementations of CBL in biomedical engineering education [6] [15], several key factors emerge as critical for success:

Stakeholder Management: Establish clear agreements with industry or clinical partners regarding their level of involvement, time investment, and intellectual property arrangements [15]

Faculty Development: Train a diverse faculty team capable of supporting the unpredictable nature of CBL where students may explore diverse solution pathways [15]

Resource Allocation: Recognize that CBL implementation requires substantial time increases in planning, student tutoring, and constant communication [6]

Balanced Structure: Provide sufficient scaffolding at the beginning of challenges while gradually reducing structure as student projects diverge and teams gain independence [15]

Technology Integration: Utilize both online learning environments for communication and resource sharing, and versatile physical spaces that support collaborative work and prototyping [15]

Challenge-based learning represents a transformative approach to biomedical engineering education that directly addresses the pressing healthcare challenges of our time. By engaging students in authentic, complex problems aligned with the grand challenges of biomedical engineering [26], CBL develops both the technical competencies and professional skills needed to drive healthcare innovation forward. The implementation frameworks, protocols, and assessment strategies outlined in this document provide a roadmap for educators seeking to bridge the gap between educational preparation and real-world healthcare needs. As biomedical engineering continues to evolve at the intersection of technological advancement and human health, educational innovation through CBL will play an increasingly critical role in preparing the next generation of biomedical innovators.

Implementing CBL: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Structured Implementation Frameworks for Biomedical Engineering Courses

Biomedical engineering (BME) education faces the persistent challenge of bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application, preparing graduates for careers in industry, research, and clinical practice. Challenge-based learning (CBL) has emerged as a robust pedagogical framework to address this need by immersing students in authentic, complex problems derived from professional practice [19]. This approach moves beyond traditional lecture-based models to create learning experiences where students collaboratively develop solutions to open-ended challenges, simultaneously building disciplinary knowledge and essential professional competencies [6].

The implementation of structured CBL frameworks is particularly critical in BME due to the field's interdisciplinary nature and the high stakes of its clinical applications. These frameworks provide the scaffolding necessary to ensure that educational experiences systematically develop both technical and professional skills, creating industry-ready engineers equipped to navigate the complexities of medical technology development, regulatory affairs, and healthcare innovation [28]. This document outlines evidence-based frameworks, protocols, and implementation strategies for effectively integrating CBL into biomedical engineering curricula.

Theoretical Foundation and Efficacy Data

Challenge-based learning operates on the fundamental principle that students learn more effectively when they actively participate in open learning experiences rather than passively receiving information in structured activities [19]. In the context of BME, this approach typically involves students collaborating with faculty, industry partners, and clinical professionals to address meaningful challenges that mirror real-world problems in healthcare technology and medical innovation.

The efficacy of CBL is supported by multiple institutional implementations. At Tecnologico de Monterrey, the Tec21 educational model has made CBL one of its four fundamental pillars, specifically aiming to develop both disciplinary competencies (knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values for professional practice) and transversal competencies (versatile skills useful across multiple domains) [19]. Research publications on CBL have grown exponentially since 2006, indicating increasing academic interest and validation of this educational approach [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Assessment of CBL Implementation in a Bioinstrumentation Course

| Assessment Metric | Pre-CBL Implementation | Post-CBL Implementation | Measurement Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Student Satisfaction | Moderate (Baseline) | Significant increase | Institutional student opinion survey [6] |

| Skill Development | Theoretical knowledge focus | New concept acquisition and skill development | Self-reported competency development [6] |

| Industry Preparedness | Limited clinical/industrial exposure | Enhanced practical understanding | Industry partner feedback and project assessment [6] |

| Interdisciplinary Integration | Discipline-specific knowledge | Effective cross-disciplinary collaboration | Observation of team dynamics and project outcomes [6] |

The NICE (New frontier, Integrity, Critical and creative thinking, Engagement) strategy represents another structured framework implemented in BME education, specifically designed to address identified gaps in traditional curricula [29]. This approach integrates cutting-edge technological awareness with ethical reasoning, critical thinking, and direct industry engagement, creating a comprehensive educational experience that aligns with CBL principles.

Framework Implementation Protocols

CBL Integration Protocol for Core BME Courses

The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for integrating challenge-based learning into undergraduate biomedical engineering courses, based on successful implementations in bioinstrumentation and design courses [6] [14].

Phase 1: Challenge Design and Partner Engagement

- Duration: 4-6 weeks pre-semester

- Objectives: Identify authentic challenges, establish industry partnerships, define learning outcomes

- Procedures:

- Industry Partner Identification: Collaborate with medical device companies, clinical departments, or research institutions to identify current, relevant problems. These organizations are formally designated as "training partners" [19].

- Challenge Formulation: Develop challenge statements that are open-ended yet scaffolded to align with course learning objectives. Example: "Design, prototype, and test a respiratory or cardiac gating device for radiotherapy" [6].

- Scope Definition: Establish clear parameters including budget constraints, regulatory considerations (e.g., FDA guidelines), and clinical requirements.

- Assessment Planning: Develop detailed rubrics evaluating both technical solutions and process skills (teamwork, communication, project management).

Phase 2: Course Structure and Support Systems

- Duration: Semester-long implementation

- Objectives: Create learning environment conducive to CBL, provide appropriate scaffolding

- Procedures:

- Team Formation: Organize students into interdisciplinary teams of 3-5 members, ensuring diversity of backgrounds and skillsets.

- Kickoff Workshop: Conduct an initial session where training partners present the challenge context and clinical/industry significance.

- Blended Learning Activities: Combine online communication platforms, laboratory experiments, and regular in-person CBL activities [6].

- Mentor Assignment: Provide each team with faculty and industry mentors who offer guided support without dictating solutions.

Phase 3: Iterative Solution Development

- Duration: 8-12 weeks within semester

- Objectives: Guide students through engineering design process, foster critical thinking

- Procedures:

- Need Identification: Teams conduct interviews with clinical experts to identify and validate unmet needs [29].

- Concept Generation: Employ structured ideation techniques (brainstorming, bio-inspired design, TRIZ) to generate multiple solutions [30].

- Prototype Development: Create physical or computational prototypes using available fabrication facilities (3D printing, micro fabrication labs) [31].