Voluntary Blink Communication Protocols: Next-Generation Assistive Technology for Patients with Severe Motor Impairments

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of voluntary blink-controlled communication protocols, a critical assistive technology for patients with conditions such as locked-in syndrome, ALS, and severe brain injury.

Voluntary Blink Communication Protocols: Next-Generation Assistive Technology for Patients with Severe Motor Impairments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of voluntary blink-controlled communication protocols, a critical assistive technology for patients with conditions such as locked-in syndrome, ALS, and severe brain injury. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the neuroscientific foundations of blink control, details cutting-edge methodological approaches from computer vision and EEG-based systems, and addresses key optimization challenges like distinguishing intentional from involuntary blinks. The content synthesizes recent validation studies and performance comparisons, offering a roadmap for integrating these technologies into clinical trials and therapeutic development to enhance patient quality of life and create novel endpoints for neurological drug efficacy.

The Neuroscience of Blink Control and Its Clinical Imperative in Severe Motor Impairments

Blinking is a complex motor act essential for maintaining ocular surface integrity and protecting the eye. For researchers developing blink-controlled communication protocols, particularly for patients with severe motor disabilities such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or locked-in syndrome, a precise understanding of the neuromuscular and neurophysiological distinctions between voluntary and reflexive blinking is paramount [1] [2] [3]. These two blink types are governed by distinct neural pathways, exhibit different kinematic properties, and are susceptible to varying pathologies [4] [1]. This document provides a detailed experimental framework for differentiating these blinks, underpinned by quantitative data and protocols, to advance the development of robust assistive technologies.

Quantitative Kinematic and Physiological Differentiation

The following tables summarize the key characteristics that experimentally distinguish voluntary and reflexive blinks. These parameters are critical for creating algorithms that can accurately classify blink types in a communication protocol.

Table 1: Kinematic and Functional Characteristics of Blink Types

| Characteristic | Voluntary Blink | Reflexive Blink (Corneal Reflex) | Clinical/Experimental Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Control | Cortical & Subcortical circuits; involves pre-motor readiness potential [1] | Brainstem-mediated; afferent trigeminal (V) & efferent facial (VII) nerves [5] [6] | Voluntary control is essential for intentional communication; reflex is a protective indicator [2] |

| Primary Function | Intentional action (e.g., for communication) [2] | Protective response to stimuli (e.g., air puff, bright light) [5] [1] | Guides the context of use in assistive devices. |

| Closing Phase Speed | Slower than reflex [5] | Faster than spontaneous/voluntary [5] | A key kinematic parameter for differentiation via video-oculography [5] |

| Conscious Awareness | Conscious and intentional [1] | Unconscious and involuntary [1] | Fundamental to the paradigm of voluntary blink-controlled systems. |

| Muscle Activation Pattern | Complex, varied patterns in the orbicularis oculi [7] | Stereotyped, consistent patterns [7] | Can be detected with high-precision EMG to improve classification accuracy [7] |

| Typical Amplitude | Can be highly variable; often full closure [1] | Consistent, often complete closure [5] | Incomplete blinks can reduce efficiency in communication systems [1] |

| Habituation | Non-habituating | R2 component habituates readily [6] [8] | Important for experimental design; repeated reflex stimulation loses efficacy. |

Table 2: Electrophysiological Blink Reflex Components

| Component | Latency (ms) | Location | Pathway | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | ~12 (Ipsilateral only) | Pons | Oligosynaptic between principal sensory nucleus of V and ipsilateral facial nucleus [6] [8] | Stable, reproducible [6] |

| R2 | ~21-40 (Bilateral) | Pons & Lateral Medulla | Polysynaptic between spinal trigeminal nucleus and bilateral facial nuclei [6] [9] [8] | Variable, habituates [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Differentiation

This section outlines standardized methodologies for eliciting, recording, and analyzing the two blink types, providing a foundation for reproducible research.

Protocol 1: Video-Oculography for Kinematic Analysis

This non-contact method is ideal for measuring blink dynamics in patient populations [5].

- Objective: To quantify the speed and completeness of voluntary and reflexive blinks using high-speed video recording.

- Equipment:

- High-speed camera (e.g., capable of ≥240 fps) [5]

- Stable headrest (e.g., chinrest)

- Consistent, oblique illumination (e.g., LED lamps at 1300 ± 100 lux) [5]

- Air jet system for reflex elicitation (e.g., syringe or solenoid valve delivering ~20 ml air puff <150 ms) [5]

- Video processing software (e.g., MATLAB)

- Procedure:

- Position the subject in the chinrest, ensuring both eyes are in the camera's field of view.

- For reflexive blink recording: Randomly activate the air jet directed at one cornea without warning the subject. Record the resulting direct (ipsilateral) and consensual (contralateral) blinks [5].

- For voluntary blink recording: Instruct the subject to blink "naturally" when needed or to blink on a specific verbal command.

- Record a 60-second sequence containing both types of blinks.

- Off-line processing: Define a region of interest (ROI) around each eye. Calculate the light intensity diffused by the eye within the ROI for each video frame. Blinks will appear as sharp peaks in this intensity curve [5].

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the intensity curve to an Exponentially Modified Gaussian (EMG) function. The parameters (σ, μ, τ) describe the dynamics of the blink's closing and opening phases [5].

- Compare the closing speed (derived from EMG parameters) between voluntary and reflexive blinks. Reflexive blinks should demonstrate a significantly faster closing phase [5].

Protocol 2: Electrophysiological Blink Reflex Testing

This protocol assesses the integrity of the trigeminal-facial brainstem pathway, which is crucial for reflexive blinks [6] [8].

- Objective: To record and measure the R1 and R2 components of the blink reflex elicited by electrical stimulation.

- Equipment:

- Clinical electrophysiology recording system

- Surface recording electrodes

- Electrical stimulator (e.g., pediatric prong stimulator)

- Ground electrode

- Procedure:

- The subject lies supine in a relaxed state, eyes open or gently closed.

- Place surface recording electrodes on the orbicularis oculi muscles bilaterally. The active electrode (G1) is placed below the eye, lateral and inferior to the pupil. The reference (G2) is placed lateral to the lateral canthus [6].

- Place the ground electrode on the mid-forehead or chin.

- Stimulate the supraorbital nerve on one side by placing the stimulator over the eyebrow.

- Use a brief electrical shock (0.1-0.2 ms duration, 5-10 mA intensity, or 2-3 times sensory threshold) [8].

- Record the EMG response from both eyes simultaneously. Allow several seconds (e.g., 10+ seconds) between stimulations to prevent habituation of the R2 component [6] [9].

- Repeat 4-6 stimuli on one side, then perform the same procedure on the contralateral side.

- Data Analysis:

- Measure the latencies of the R1 (ipsilateral) and R2 (bilateral) responses from the stimulus artifact to the onset of the EMG potential.

- Compare latencies to normative data. An afferent pattern (delayed R2 bilaterally when stimulating the affected side) suggests trigeminal nerve pathology. An efferent pattern (delayed R2 on the affected side regardless of stimulation side) suggests facial nerve pathology [6] [8].

Protocol 3: Voluntary Blink Training for Timed Responses

This protocol is directly relevant to training patients to use voluntary blinks for communication [10].

- Objective: To train subjects to produce well-timed voluntary blink responses to a neutral conditional stimulus (CS).

- Equipment:

- Eyelid movement recording system (e.g., magnetic search coil or EOG) [10]

- Auditory or visual feedback system

- Procedure:

- Instruct the subject that they will hear a tone (CS) and should try to blink with a specific delay after it (e.g., 300 or 500 ms).

- Provide feedback to guide learning. This can be:

- Conduct a series of trials (e.g., 40 with feedback), followed by trials without feedback to test retention.

- The subject can be trained to associate different blink patterns (e.g., single vs. double blink) with distinct commands.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the percentage of correctly timed responses (onset >150 ms after CS and before the target).

- Analyze the onset and peak latency of the blinks to assess timing accuracy. Studies show humans can voluntarily learn to time blinks with high accuracy, comparable to classically conditioned blinks [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Blink Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Camera (≥240 fps) | Captures rapid eyelid kinematics for detailed analysis of speed and completeness [5] | Video-oculography protocol for differentiating blink types [5] |

| Surface EMG Electrodes | Records electrical activity from the orbicularis oculi muscle [7] [6] | Blink reflex testing and studying muscle activation patterns [6] [8] |

| Electrical Stimulator | Elicits a standardized, quantifiable blink reflex via supraorbital nerve stimulation [6] [8] | Clinical neurophysiology assessment of cranial nerves V and VII [6] |

| Solenoid Valve Air Puff System | Delivers a consistent, brief air jet to the cornea to elicit a protective reflex blink [5] [10] | Kinematic studies of reflexive blinks without electrical stimulation [5] |

| Electrooculography (EOG) | Measures corneo-retinal potential to detect eye movements and blinks [2] [3] | Assistive device input for bed-ridden patients; detects high-amplitude voluntary blinks [2] |

| Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | Interfaces sensors (EMG, EOG, camera) with a computer for signal processing and analysis [2] | Core component of any custom-built blink recording or assistive device system [2] |

| MATLAB with Custom Scripts | For offline processing of video intensity curves, EMG signals, and kinematic parameter extraction [5] [10] | Data analysis in kinematic and voluntary blink training protocols [5] [10] |

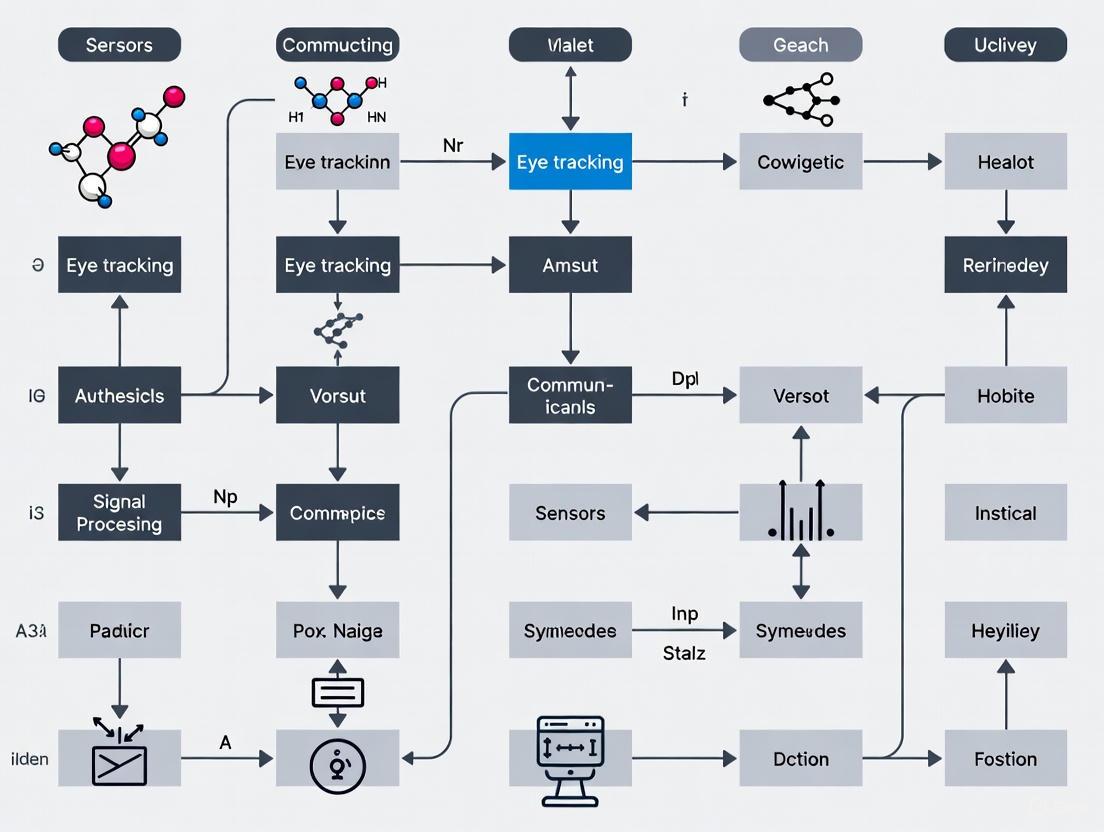

Neural Pathway Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the distinct neural circuits governing voluntary and reflexive blinks, which is fundamental to understanding their differential control.

Diagram 1: Neuromuscular Pathways of Blinking. The voluntary pathway (red/orange) involves cortical decision-making centers descending through subcortical structures to the brainstem. The reflexive pathway (green) is a brainstem-mediated loop involving the trigeminal and facial nerves, bypassing higher cortical centers for rapid protection.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Blink Differentiation. A unified protocol for distinguishing blink types through simultaneous kinematic and electrophysiological recording, culminating in data analysis that classifies blinks for use in assistive communication systems.

Epidemiological Data on TBI and ALS Risk

Recent large-scale epidemiological studies provide critical insights into the relationship between Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and the subsequent risk of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). The data reveals a complex, time-dependent association crucial for researchers to consider in patient population studies.

Table 1: Key Epidemiological Findings from a UK Cohort Study on TBI and ALS Risk [11] [12] [13]

| Parameter | Study Cohort (n=85,690) | Matched Comparators (n=257,070) | Hazard Ratio (HR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall ALS Risk | Higher incidence | Baseline reference | 2.61 (95% CI: 1.88-3.63) |

| Risk within 2 years post-TBI | Significantly higher incidence | Baseline reference | 6.18 (95% CI: 3.47-11.00) |

| Risk beyond 2 years post-TBI | No significant increase | Baseline reference | Not significant |

| Median Follow-up Time | 5.72 years (IQR: 3.07-8.82) | 5.72 years (IQR: 3.07-8.82) | - |

| Mean Age at Index Date | 50.8 years (SD: 17.7) | 50.7 years (SD: 17.6) | - |

This data suggests that the elevated ALS risk following TBI may indicate reverse causality, where the TBI event itself could be an early consequence of subclinical ALS, such as from falls due to muscle weakness, rather than a direct causative factor [11] [14]. For researchers, this underscores the importance of careful patient history taking and timeline establishment when studying these populations.

Locked-In Syndrome in ALS: Communication Protocols and Pathophysiology

Locked-In Syndrome (LIS), a condition of profound paralysis with preserved consciousness, represents a critical end-stage manifestation for a subset of ALS patients. Establishing reliable communication protocols is a primary research and clinical focus.

Table 2: Communication Modalities for LIS Patients [15]

| Modality Category | Description | Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| No-Tech | Relies on inherent bodily movements without tools. | Coded blinking, vertical eye movements, residual facial gestures. | Requires a trained communication partner; susceptible to fatigue and error. |

| Low-Tech | Utilizes simple, non-electronic materials. | Eye transfer (ETRAN) boards, letter boards, low-tech voice output devices. | Leverages preserved ocular motility; cost-effective and readily available. |

| High-Tech AAC | Employs advanced electronic devices. | Eye-gaze tracking systems, tablet-based communication software. | Offers greater communication speed and autonomy; requires setup and calibration. |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) | Uses neural signals to control an interface, bypassing muscles. | Non-invasive (EEG-based) systems; invasive (implanted electrode) systems. | The only option for patients with complete LIS (no eye movement); active research area. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Blink-Controlled Communication System

The following protocol outlines a standardized methodology for establishing and validating a blink-controlled communication system for patients with LIS, suitable for research and clinical application.

Phase 1: Assessment and Baseline Establishment

- Confirm Consciousness and Cognitive Capacity: Before establishing communication, confirm the patient's level of consciousness and ability to follow commands. This is a prerequisite for reliable communication [15] [16].

- Establish a Reliable "Yes/No" Response: Work with the patient to define a consistent, reproducible motor signal. Blinking is the most common, but vertical eye movements or a residual facial twitch may be used. Test for reliability by asking simple, verifiable questions [15].

- Document Baseline Function: Record the patient's specific motor capabilities, blink endurance, and any factors that may affect performance (e.g., fatigue, spasticity) [17].

Phase 2: System Implementation and Training

- Select the Encoding Method:

- Alphabet Board Scanning: A communication partner slowly points to letters or groups of letters on a board. The patient blinks to select.

- Coded Blink System: Implement a code, such as one blink for "yes," two for "no," and a more complex sequence (e.g., prolonged blink) to initiate spelling using a pre-agreed alphabet sequence.

- Calibration and Training Sessions: Conduct short, frequent training sessions to minimize fatigue. Begin with simple single-letter selection and progress to word formation. Quantify accuracy and speed [15] [18].

- Introduce Low-Tech Aids: Introduce an E-Tran (Eye Transfer) board—a transparent board with letters—allowing the partner to see where the patient is looking from the opposite side [15].

Phase 3: Validation and Proficiency Measurement

- Standardized Testing: Assess proficiency using standardized word- or sentence-spelling tasks. Calculate the information transfer rate (bits per minute) and accuracy percentage.

- Fatigue Monitoring: Record the maximum sustainable communication session duration and monitor for a decline in accuracy over time, which indicates fatigue.

- Quality of Life (QoL) Assessment: Use standardized QoL questionnaires, adapted for yes/no responses, to subjectively evaluate the impact of the communication system from the patient's perspective [15].

Phase 4: Advanced Integration (If Applicable)

- Transition to High-Tech Systems: For patients with stable blink control, consider transitioning to an eye-gaze tracking computer system, which can offer greater independence and access to more complex communication functions [15].

- BCI Evaluation: For patients who lose all voluntary muscle control, including blinking (progressing to complete LIS), evaluate for BCI systems that rely on neural signals alone [15] [17] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Tools for ALS and LIS Investigation [19] [17] [20]

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| ILB (LMW-Dextran Sulphate) | Investigational drug that induces release of Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), providing a neurotrophic and myogenic stimulus. | Used in Phase IIa clinical trials; administered via subcutaneous injection [19]. |

| BIIB105 (Antisense Oligonucleotide) | Investigational drug designed to reduce levels of ataxin-2 protein, which may help reduce toxic TDP-43 clusters in ALS. | Evaluated in the ALSpire trial; administered intrathecally [20]. |

| Medtronic Summit System | A fully implantable, rechargeable Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system for chronic recording of electrocorticographic (ECoG) signals. | Used in clinical trials to enable communication for patients with severe LIS by decoding motor intent [17]. |

| Riluzole | Standard-of-care medication that protects motor neurons by reducing glutamate-induced excitotoxicity. | Often a baseline treatment in clinical trials; patients typically continue use [17] [18]. |

| ALSFRS-R Scale | Functional rating scale used as a key efficacy endpoint in clinical trials to measure disease progression. | Tracks speech, salivation, swallowing, handwriting, and other motor functions [19]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The following diagrams visualize key pathophysiological concepts and experimental workflows relevant to ALS and LIS research.

TBI-ALS Risk Relationship Pathway

This diagram illustrates the hypothesized "reverse causality" pathway explaining the time-dependent association between TBI and ALS diagnosis.

Blink Communication Protocol Workflow

This diagram outlines the step-by-step experimental protocol for establishing a blink-controlled communication system, as detailed in Section 2.1.

The detection and interpretation of conscious awareness in patients with severe motor impairments represent a frontier in clinical neuroscience. This article details the experimental protocols and technological frameworks enabling the use of voluntary blink responses as a critical communication channel. We provide application notes on computer vision, wearable sensor systems, and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that decode covert awareness and facilitate overt communication for patients with disorders of consciousness, including locked-in syndrome (LIS). Structured data on performance metrics and a comprehensive toolkit for researchers are included to standardize methodologies across the field.

Consciousness assessment in non-responsive patients is a profound clinical challenge. An estimated 15–25% of acute brain injury (ABI) patients may experience covert consciousness, aware of their environment but demonstrating no overt motor signs [21]. Locked-in Syndrome (LIS), characterized by full awareness amidst near-total paralysis, further underscores the critical need for reliable communication pathways [15]. The eyelid and ocular muscles, often spared in such injuries, provide a biological substrate for interaction. Voluntary blinks, distinct in amplitude and timing from involuntary reflexes, can be harnessed as a robust voluntary motor signal for communication [10] [22]. This article outlines the protocols and technologies translating this biological signal into a functional communication protocol, bridging the gap between covert awareness and overt interaction.

Application Notes: Technologies for Blink Detection and Communication

Computer Vision-Based Detection

Overview: Computer vision algorithms can detect subtle, low-amplitude facial movements imperceptible to the human eye, allowing for the identification of command-following in seemingly unresponsive patients.

Key Evidence: The SeeMe tool, a computer vision-based system, was tested on 37 comatose ABI patients (Glasgow Coma Scale ≤8). It detects facial movements by tracking individual facial pores at a high resolution (~0.2 mm) and analyzing their displacement in response to auditory commands [21].

Performance Metrics:

- Earlier Detection: SeeMe detected eye-opening in comatose patients 4.1 days earlier than clinical examination [21].

- Higher Sensitivity: SeeMe identified eye-opening in 85.7% (30/36) of patients, compared to 71.4% (25/36) via clinical examination [21].

- Correlation with Outcome: The amplitude and frequency of SeeMe-detected responses were correlated with functional outcomes at hospital discharge [21].

Wearable Sensor-Based Interfaces

Overview: Wearable technologies, such as thin-film pressure sensors and smart contact lenses, offer an alternative to camera-based systems, providing continuous, portable, and robust blink monitoring.

Key Evidence:

- Pressure Sensors: Systems using thin-film pressure sensors capture delicate deformations from ocular muscle movements. One study evaluated six voluntary blink actions (e.g., single/double/triple, unilateral/bilateral) and found single bilateral blinks (SB) had the highest recognition accuracy (96.75%) and were among the most efficient and comfortable for users [23].

- Wireless Contact Lenses: A novel wireless "EMI contact lens" incorporates a mechanosensitive capacitor and inductive coil to form an RLC oscillating loop. Eyelid pressure during a conscious blink (approx. 30 mmHg) changes the lens curvature, altering the circuit's resonant frequency to encode commands. This system has enabled the control of external devices, such as drones, via multi-route blink patterns [24].

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) and AAC

Overview: For patients in a total LIS state without any voluntary eye movement, BCIs can translate neural signals directly into commands.

Key Evidence: BCIs are categorized as invasive or non-invasive. Non-invasive BCIs, which include interfaces that can be controlled by blinks, provide a vital communication link. The establishment of a functional system is a key component for maintaining and improving the quality of life for LIS patients [15]. The communication hierarchy progresses from no-tech (e.g., coded blinking) to low-tech (e.g., E-Tran boards) to high-tech (e.g., eye-gaze trackers and BCIs) solutions [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Summary of Blink Detection Technologies

| Technology | Key Metric | Performance Value | Study Population | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computer Vision (SeeMe) | Detection Lead Time | 4.1 days earlier than clinicians | 37 ABI patients | [21] |

| Sensitivity (Eye-Opening) | 85.7% (30/36 patients) | 37 ABI patients | [21] | |

| Pressure Sensor (SB Action) | Recognition Accuracy | 96.75% | 16 healthy volunteers | [23] |

| Wireless Contact Lens | Pressure Sensitivity | 0.153 MHz/mmHg | Laboratory and human trial | [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computer Vision for Covert Consciousness Detection

This protocol is designed to identify command-following in patients with ABI who do not respond overtly.

1.1 Participant Setup and Calibration

- Position a high-frame-rate camera (e.g., 30-60 fps) approximately 1-1.5 meters from the patient's face, ensuring clear visibility of the entire facial region.

- Conduct a baseline recording for 1 minute while the patient is at rest to establish individual movement baselines [21].

1.2 Auditory Command Stimulation

- Use pre-recorded auditory commands delivered via noise-isolating headphones to ensure consistency and minimize external noise. Core commands include: "Open your eyes," "Stick out your tongue," and "Show me a smile" [21].

- Present commands in blocks of 10 repetitions for each command type.

- Implement a variable inter-stimulus interval of 30-45 seconds (±1 sec jitter) to prevent habituation and prediction [21].

1.3 Data Acquisition and Processing

- Record video data throughout the session.

- Process videos using the SeeMe algorithm or similar computer vision pipeline, which involves:

- Facial Landmark Tracking: Identify and track key facial features or pores.

- Vector Field Analysis: Quantify the magnitude and direction of pixel movement between frames.

- Response Window Analysis: Analyze a window of 0-20 seconds post-command for significant movements in the relevant region of interest (e.g., mouth for "stick out your tongue") [21].

1.4 Data Analysis and Validation

- Compare algorithm outputs with simultaneous clinical scores (e.g., Coma Recovery Scale-Revised, Glasgow Coma Scale).

- Validate findings against independent, blinded human raters who review the video recordings [21].

Computer vision workflow for covert consciousness detection.

Protocol 2: Establishing a Voluntary Blink Communication Code

This protocol defines a method for creating a functional yes/no or choice-making system using voluntary blinks.

2.1 Establishing a Reliable "Yes/No" Signal

- Work with the patient and clinical team to define two distinct, reproducible blink patterns. A common standard is:

- "Yes": One voluntary blink.

- "No": Two voluntary blinks in quick succession.

- During training, present simple, verifiable questions (e.g., "Is your name John?"). Provide feedback to shape the accuracy and consistency of the response.

- Confirm response reliability by achieving >95% accuracy on a set of 10 verifiable questions before proceeding [15].

2.2 Implementing a Blink-Controlled AAC System

- For patients with preserved vertical eye movement, an E-Tran (Eye Transfer) board can be used. This is a transparent board with letters and common phrases arranged around the edges. The communication partner holds the board between themselves and the patient, and the patient communicates by looking toward specific areas on the board, often confirmed with a blink [15].

- For higher-throughput communication, integrate with a high-tech eye-gaze tracking device. Here, blinks can be used as a selection command. For example:

- The user looks at a virtual keyboard on a screen.

- A sustained blink (e.g., >500ms) acts as a "click" to select the letter or icon under gaze.

2.3 Coding Complex Commands with Blink Patterns

- Map more complex commands to specific blink sequences. The pressure sensor study suggests starting with the most robust actions [23]:

- Single Bilateral Blink (SB): Primary selection command.

- Double Bilateral Blink (DB): "Go back" or cancel command.

- Single Unilateral Blink (SU): Mode shift or secondary menu access.

- System training should focus on these core actions before introducing more complex patterns like triple blinks.

Protocol for establishing a blink communication code.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Voluntary Blink Communication Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Camera | Captures facial movements and blink kinematics for computer vision analysis. | Frame rate ≥60 fps; resolution ≥1080p; used in the SeeMe protocol for tracking subtle facial movements [21]. |

| Thin-Film Pressure Sensor | Detects mechanical deformation from eyelid movements for wearable blink detection. | Small size, low power consumption; placed near the eye to detect blink force with high accuracy (~96.75% for single blinks) [23]. |

| Wireless Smart Contact Lens | Encodes blink information via changes in intraocular pressure and corneal curvature. | Contains a mechanosensitive capacitor and inductive coil (RLC loop); enables wireless, continuous monitoring and command encoding [24]. |

| Electrooculography (EOG) | Records the corneo-retinal standing potential to detect eye and eyelid movements. | Traditional method for capturing blink dynamics; provides excellent temporal synchronization [22]. |

| Eye Openness Algorithm | Classifies blinks from video by estimating the distance between eyelids, rather than relying on pupil data loss. | Provides more detailed blink parameters (e.g., duration, amplitude) compared to pupil-size-based methods; available in some commercial eye trackers (e.g., Tobii Pro Spectrum) [22]. |

| E-Tran (Eye Transfer) Board | A no-tech communication aid for patients with voluntary eye movements. | A transparent board with letters/words; the user looks at targets to spell words, often confirmed with a blink [15]. |

| Eye-Gaze Tracking System | A high-tech AAC device that allows control of a computer interface via eye movement. | The user looks at on-screen keyboards; a voluntary blink is often used as the selection mechanism [15]. |

Application Note: Biological Foundations and Quantitative Analysis

Voluntary eye blinks represent a robust biological signal emanating from a preserved oculomotor system, making them ideal for alternative communication protocols in patients with severe motor disabilities such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) [25]. This application note details the biological basis, measurement methodologies, and experimental protocols for implementing blink-based communication systems. By leveraging the neurological underpinnings of blink control and modern computer vision techniques, researchers can develop non-invasive communication channels that remain functional even when other motor systems deteriorate. The core advantage lies in the preservation of oculomotor function despite progressive loss in other motor areas, providing a critical communication pathway for affected individuals.

Neurobiological Basis of Blink Control

The human blink system involves complex neural circuitry that remains functional in various pathological conditions:

- Dual Control System: Blinks are regulated through both reflexive pathways (brainstem-mediated) and voluntary pathways (cortical-mediated) [26]. This dual control system ensures that even when reflexive blinks occur approximately 15 times per minute spontaneously, voluntary blinks can be independently controlled for communication purposes.

- Muscle Kinetics: A blink involves the rapid inhibition of the levator palpebrae muscle followed by contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle, creating a characteristic down-phase (75-100 ms) and up-phase (longer duration) [26]. The entire blink cycle typically lasts 100-400 milliseconds, with voluntary blinks demonstrating distinct kinematic profiles from spontaneous blinks [27] [26].

- Perceptual Stability Mechanisms: Crucially, the brain maintains perceptual continuity during blinks through active suppression mechanisms [26]. This neurological filtering allows voluntary blinks to be used as intentional signals without causing significant visual disruption to the user.

Quantitative Blink Parameters for Communication Systems

Table 1: Clinically Significant Blink Parameters for Communication Protocol Design

| Parameter | Typical Range | Communication Significance | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | 100-400 ms [27] | Determines minimum detection window; affects communication rate | High-frame-rate video (240+ fps) [27] or eye-openness signal [22] |

| Amplitude | Complete vs. Incomplete closure [22] | Distinguishes voluntary from spontaneous blinks; enables multiple command levels | Eye-openness signal or eyelid position tracking [22] |

| Velocity | Down-phase: 16-19 cm/s [26] | Kinematic signature of intentionality | Derivative of eyelid position signal [27] |

| Temporal Pattern | Variable inter-blink intervals | Enables coding of complex messages through timing patterns | Timing between sequential voluntary activations [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Frame-Rate Video Blink Detection

Purpose and Scope

This protocol details a non-contact method for quantifying blink parameters using high-frame-rate video capture, suitable for long-term monitoring in natural environments [27]. The approach overcomes limitations of traditional bio-signal methods like electro-oculography (EOG) that require physical attachments and are susceptible to signal artifacts from facial muscle contractions [27].

Equipment Setup

- Camera System: High-frame-rate camera capable of ≥240 fps capture (e.g., Casio EX-ZR200 or smartphone with high-speed video capability) [27]

- Spatial Resolution: Minimum 512×384 pixels, though higher resolutions (1920×1080) improve accuracy [27]

- Lighting: Consistent ambient lighting to minimize pupil adaptation effects

- Positioning: Camera mounted above display monitor, focused on participant's facial region

Data Acquisition Procedure

- Participant Positioning: Position participant 50-70 cm from camera with face centered in frame

- Calibration: Record 30-second baseline with participant maintaining open gaze for reference measurements

- Task Administration: Present visual stimuli on monitor while recording facial video

- Duration: Capture sessions of 10-15 minutes, allowing for natural variation in blink patterns

Data Processing Pipeline

Table 2: Video Processing Workflow for Blink Parameter Extraction

| Processing Stage | Algorithm/Method | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Face Detection | Haar cascades or deep learning models | Bounding coordinates of facial region |

| ROI Extraction | Facial landmark detection | Specific eye region coordinates |

| Blink Segmentation | Grayscale intensity profiling or event signal generation [27] | Putative blink sequences (excluding flutters/microsleeps) |

| Parameter Quantification | Frame-by-frame eyelid position analysis [27] | Duration, amplitude, velocity metrics |

| Classification | Threshold-based or machine learning classification | Voluntary vs. spontaneous blink identification |

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based Voluntary Blink Detection

Purpose and Scope

This protocol implements a real-time blink detection system using machine learning classification to distinguish voluntary blinks from spontaneous blinks for human-computer interaction [25]. The system operates using consumer-grade hardware, enhancing accessibility and deployment potential.

System Architecture

- Hardware: Standard webcam (30 fps minimum, higher rates preferred)

- Software Pipeline: Face detection → face alignment → ROI extraction → eye-state classification [25]

- Auxiliary Components: Rotation compensation, ROI quality assessment, temporal filtering

Training Dataset Development

- Data Collection: Capture eye-state images under varied lighting conditions and head positions

- Dataset Annotation: Manually label images as "open", "closed", or "partial" states

- Dataset Partitioning: Create separate training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15 split)

Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Train both CNN (non-linear classification) and SVM (linear separation) models for comparison [25]

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score

- Cross-Validation: Test performance across multiple datasets (e.g., CeW, ZJU, Eyeblink) [25]

- Real-Time Implementation: Optimize model for inference speed to achieve real-time performance

Visualization of Blink Processing Workflows

Blink Detection and Classification Pathway

Neural Control of Voluntary Blinking

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Blink Communication Research

| Item | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Speed Camera | ≥240 fps, ≥512×384 resolution [27] | Captures blink kinematics with sufficient temporal resolution |

| Eye-Openness Algorithm | Pixel-based eyelid distance estimation [22] | Quantifies blink amplitude and completeness directly |

| Blink Classification Dataset | YEC and ABD datasets [25] | Trains and validates machine learning models for eye-state classification |

| Video Processing Pipeline | ROI extraction + intensity profiling [27] | Segments blink events from continuous video data |

| Temporal Filter | Moving average or custom algorithm [25] | Reduces classification noise and improves detection accuracy |

| Performance Metrics Suite | F1-score, accuracy, precision, recall [25] | Quantifies system reliability and communication accuracy |

Communication is a fundamental human need, and its loss represents one of the most profound psychosocial stressors an individual can face. For patients with severe motor impairments resulting from conditions such as Locked-In Syndrome (LIS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and brainstem injuries, the inability to communicate leads to devastating social isolation and significantly diminished quality of life [28] [29]. This application note explores the intricate relationship between communication loss and psychosocial well-being, framed within the context of emerging blink-controlled communication protocols. We provide a comprehensive analysis of the neurobiological impact of isolation, detailed experimental protocols for blink-based communication systems, and standardized metrics for evaluating their efficacy in restoring social connection and improving patient outcomes.

Psychosocial and Neurobiological Impact of Communication Loss

The Isolation-Health Pathway

Communication loss creates a cascade of detrimental effects on mental and physical health through multiple pathways. Social isolation and loneliness are established independent risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality, with evidence pointing to plausible biological mechanisms [30].

Mental Health Correlates: Robust longitudinal studies demonstrate that social isolation and loneliness significantly increase the risk of developing depression, with the odds more than doubling among those who often feel lonely compared to those rarely or never feeling lonely [30]. Mendelian randomization studies suggest a bidirectional causal relationship, where loneliness both causes and is caused by major depression [30].

Cognitive Consequences: Strong social connection is associated with better cognitive function, while isolation presents risk factors for dementia. Meta-analyses involving over 2.3 million participants show that living alone, smaller social networks, and infrequent social contact increase dementia risk [30].

Physical Health Implications: Substantial evidence links poor social connection to increased incidence of cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and diabetes mellitus [30]. The strength of this evidence has been acknowledged in consensus reports from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the US Surgeon General [30].

Neurobiological Mechanisms

Animal models and human studies reveal specific neurobiological alterations induced by social isolation stress:

HPA Axis Dysregulation: Social separation stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing basal corticosterone levels and inducing long-lasting changes in stress responsiveness [31]. These alterations are particularly pronounced when isolation occurs during critical neurodevelopmental periods [31].

Monoaminergic System Alterations: Early social isolation stress induces long-lasting reductions in serotonin turnover and alterations in dopamine receptor sensitivity [31]. These neurotransmitter systems are implicated in addictive, psychotic, and affective disorders, providing a mechanistic link between isolation and mental health pathology.

Neural Circuitry Changes: Social isolation during development alters functional development in medial prefrontal cortex Layer-5 pyramidal cells and enhances activity of inhibitory neuronal circuits [31]. Human studies of severely deprived children show alterations in white matter tracts, though early intervention can rescue some of these changes [31].

Table 1: Neurobiological Correlates of Social Isolation Stress

| Biological System | Observed Alterations | Behavioral Correlates |

|---|---|---|

| HPA Axis | Increased basal corticosterone, CRF activity, glucocorticoid resistance [31] | Heightened stress response, affective dysregulation |

| Serotonin System | Reduced serotonin turnover, altered 5-HIAA concentrations [31] | Increased depression and anxiety-like behaviors |

| Dopamine System | Altered receptor sensitivity [31] | Reward processing deficits, increased addiction vulnerability |

| Neural Structure | Dendritic loss, reduced synaptic plasticity, altered myelination [31] | Impaired executive function, facilitated fear learning |

Blink-Controlled Communication Systems: Technical Approaches

System Classifications and Modalities

Blink-controlled communication systems represent a critical technological approach to restoring communication for severely paralyzed patients. These systems can be broadly categorized into three main types:

No-Tech Systems: Communication relies solely on bodily movements without additional materials. Examples include using specific eye movements (blinking, looking up-down, or right-left) with predetermined meanings [28]. These approaches require both communication partners to be aware of the specific movement-language mapping.

Low-Tech Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC): Incorporates materials such as letter boards (e.g., Eye Transfer [ETRAN] Board or EyeLink Board) where selection occurs via eye fixation or blinking [28]. These systems are low-cost but require constant caregiver presence for interpretation.

High-Tech AAC: Utilizes technology including eye-gaze switches, eye tracking, or brain-computer interfaces (BCI) to control electronic devices for communication [28] [29]. These systems offer greater independence but vary significantly in cost and complexity.

Table 2: Comparison of Blink-Controlled Communication Modalities

| System Type | Examples | Cost Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Tech | Blink coding, eye movement patterns [28] | None | Immediately available, no equipment | Limited vocabulary, requires trained partner |

| Low-Tech AAC | E-tran board, EyeLink board [28] [29] | ~$260 [29] | Low cost, portable | Requires observer, slower communication rate |

| High-Tech Sensor-Based | Tobii Dynavox, specialized eye trackers [29] | $5,000-$10,000 [29] | Independent use, larger vocabulary | High cost, technical complexity |

| High-Tech Vision-Based | Blink-To-Live, Blink-to-Code [29] [32] | Low (uses standard hardware) | Cost-effective, adaptable | Lighting dependencies, calibration required |

Specific System Architectures

Blink-To-Live System: This computer vision-based approach utilizes a mobile phone camera to track patient's eyes through real-time video analysis. The system defines four key alphabets (Left, Right, Up, and Blink) that encode more than 60 daily life commands as sequences of three eye movement states [29]. The architecture includes:

- Facial landmarks detection using MediaPipe's face mesh with 468 facial landmarks [32]

- Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR) calculation for blink detection

- Sequence decoding with native speech output

Blink-to-Code System: This implements Morse code communication through voluntary eye blinks classified as short (dot) or long (dash) [32]. The system operates through:

- Real-time EAR calculation from eye landmarks

- Duration-based classification (short blink: 1.0-2.0 seconds, long blink: ≥2.0 seconds)

- Character commitment after pause exceeding 1.0 second, word space after 3.0 seconds

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Metrics

Protocol for Blink-Based Communication Assessment

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and usability of blink-controlled communication systems in patients with severe motor impairments.

Participant Selection:

- Inclusion: Diagnosis of LIS, ALS, or severe brainstem injury with preserved eye movements and cognitive function

- Exclusion: Significant visual impairment, profound cognitive deficits, or inability to provide consent

- Sample Size: 5-20 participants based on feasibility (similar to [33] [32])

Experimental Setup:

- Environment: Well-lit, controlled environment with minimal distractions

- Equipment: Standard webcam or mobile device camera positioned approximately 50cm from participant [32]

- Software: Computer vision pipeline (OpenCV, MediaPipe) for facial landmark detection [32]

Assessment Protocol:

- Calibration Phase: Individual calibration of EAR thresholds and blink duration parameters (5 minutes)

- Training Phase: Familiarization with system operation and basic commands (10 minutes)

- Testing Phase:

- Simple phrase communication ("SOS", "YES/NO") - 5 trials each

- Complex phrase communication ("HELP", daily needs) - 5 trials each

- Free communication: Expression of needs or discomfort - 5 minutes

Data Collection:

- Accuracy: Percentage of correctly interpreted commands [32]

- Response Time: Time from initiation to correct message completion [32]

- User Experience: Subjective feedback on ease of use and comfort

- Psychosocial Measures: Pre-post assessment of mood, isolation, and communication satisfaction

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: Blink-Based Communication System Performance

| Performance Metric | Reported Values | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Message Accuracy | 62% average (range: 60-70%) [32] | Controlled trials with 5 participants |

| Response Time | 18-20 seconds for short messages [32] | "SOS" and "HELP" messaging tasks |

| ON/OFF State Prediction | AUC-ROC = 0.87 [33] | Parkinson's disease symptom monitoring |

| Dyskinesia Prediction | AUC-ROC = 0.84 [33] | Parkinson's disease symptom monitoring |

| MDS-UPDRS Part III Correlation | ρ = 0.54 [33] | Parkinson's disease symptom severity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Blink Communication Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| MediaPipe Face Mesh | Facial landmark detection for EAR calculation [32] | 468 facial landmarks, real-time processing |

| OpenCV Library | Computer vision operations and image processing [32] | Open-source, supports multiple languages |

| Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR) | Metric for blink detection from facial landmarks [32] | EAR = (‖p2−p6‖+‖p3−p5‖)/(2⋅‖p1−p4‖) |

| Standard Webcam | Video capture for vision-based systems | 720p minimum resolution, 30fps |

| Electromyography (EMG) | Measurement of electrical muscle activity for alternative blink detection [34] | Requires electrodes, higher accuracy but less comfortable |

| E-Tran Board | Low-tech communication reference for validation [29] | Transparent board with printed letters |

| Tobii Dynavox | High-tech eye tracking system for comparative studies [29] | Commercial system, $5,000-$10,000 |

Visualizing System Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Blink Detection and Classification Workflow

Isolation-Communication-Psychosocial Pathway

The implementation of blink-controlled communication protocols represents a critical intervention for addressing the profound psychosocial consequences of communication loss. Evidence demonstrates that these systems can effectively restore basic communication capabilities, thereby mitigating the detrimental effects of social isolation on mental and physical health. While current systems show promising accuracy and usability, further research is needed to optimize response times, expand vocabulary capacity, and enhance accessibility across diverse patient populations and resource settings. The integration of standardized assessment protocols and quantitative metrics, as outlined in this application note, will facilitate comparative effectiveness research and accelerate innovation in this vital area of assistive technology.

Implementing Blink Detection Systems: From Computer Vision to Brain-Computer Interfaces

The Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR) is a quantitative metric central to many modern, non-invasive eye-tracking systems. It provides a computationally simple yet robust method for detecting eye closure by calculating the ratio of distances between specific facial landmarks around the eye. The core principle is that this ratio remains relatively constant when the eye is open but approaches zero rapidly during a blink [35]. This modality is particularly valuable for developing voluntary blink-controlled communication protocols, as it allows for the reliable distinction between intentional blinks and involuntary eye closures using low-cost, off-the-shelf hardware like standard webcams [36] [35]. Its non-invasive nature and high accuracy make it a cornerstone for assistive technologies aimed at patients with conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or locked-in syndrome, enabling communication through coded blink sequences without the need for specialized sensors or electrodes [37] [3].

Core Computational Methodology and Key Parameters

EAR Calculation and Blink Identification

The implementation of EAR begins with the detection of facial landmarks. A typical model identifies six key points (P1 to P6) around the eye, encompassing the corners and the midpoints of the upper and lower eyelids [35]. The EAR is calculated as a function of the vertical eye height relative to its horizontal width, providing a scale-invariant measure of eye openness.

The formula for the Eye Aspect Ratio is defined as follows:

EAR = (||P2 - P6|| + ||P3 - P5||) / (2 * ||P1 - P4||)

where P1 to P6 are the 2D coordinates of the facial landmarks. This calculation results in a single scalar value that is approximately constant when the eye is open and decreases towards zero when the eye closes [35]. A blink is detected when the EAR value falls below a predefined threshold. Empirical research has identified 0.18 to 0.20 as an optimal threshold range, offering a strong balance between sensitivity and specificity [35]. For robust detection against transient noise, a blink is typically confirmed only if the EAR remains below the threshold for a consecutive number of frames (e.g., 2-3 frames in a 30 fps video stream).

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics and parameters for EAR-based blink detection systems as established in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics and System Parameters for EAR-based Blink Detection

| Parameter / Metric | Reported Value / Range | Context and Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal EAR Threshold | 0.18 - 0.20 | Lower thresholds (e.g., 0.18) provide best accuracy; higher values decrease performance. | [35] |

| Typical Open-Eye EAR | ~0.28 - 0.30 | Baseline value for an open eye; subject to minor individual variation. | [35] |

| Accuracy (Model) | Up to 99.15% | Achieved by state-of-the-art models (e.g., Vision Transformer) on eye-state classification tasks. | [38] |

| Spontaneous Blink Rate | 17 blinks/minute (average) | Varies with activity: 4-5 (low) to 26 (high) blinks per minute. | [35] |

| Blink Duration (from EO signal) | ~60 ms longer than PS-based detection | Eye Openness (EO) signal provides more detailed characterization. | [22] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, efficiency, real-time performance | Requires only basic calculations on facial landmark coordinates. | [35] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Real-Time Blink Detection for Communication

This protocol outlines the steps to implement a real-time blink detection system for a voluntary blink-controlled communication aid.

- Hardware Setup: Use a standard computer or smartphone with a built-in or external webcam. Ensure adequate and consistent lighting on the user's face to minimize shadows and glare [39].

- Software Initialization:

- Initialize the camera with a resolution of at least 640x480 pixels and a frame rate of 30 fps.

- Load a pre-trained facial landmark detector (e.g., the 68-point model from Dlib).

- System Calibration:

- Position the user so their face is clearly visible to the camera.

- The system may optionally record a short (5-10 second) baseline video of the user with eyes open and closed to fine-tune the EAR threshold, though a default of 0.18 can be used [35].

- Real-Time Processing Loop:

- Frame Capture: Acquire a video frame.

- Face and Landmark Detection: Detect the face in the frame and localize the 6 periocular landmarks for each eye.

- EAR Calculation: Compute the EAR for each eye using the formula in Section 2.1.

- Blink Classification: Compare the EAR to the threshold. If the EAR is below the threshold for 3 consecutive frames, register a "blink" event.

- Communication Protocol Logic:

- Implement a state machine to interpret blink sequences. For example:

- A short blink (below a duration threshold, e.g., 1 second) could select a menu item.

- A long blink (exceeding a duration threshold) could activate a command.

- A series of two blinks in quick succession could represent a special command.

- Map decoded sequences to pre-defined phrases or commands, which are then displayed on screen or converted to synthesized speech [36].

- Implement a state machine to interpret blink sequences. For example:

Protocol for Validation Against Ground Truth

To validate the accuracy of an EAR-based blink detector, the following protocol is recommended.

- Dataset Curation:

- Utilize publicly available datasets such as the MRL Eye Dataset, Eyeblink8, or TalkingFace which contain annotated videos of eyes in open and closed states [35] [38].

- Alternatively, create a custom dataset with simultaneous recording using a high-speed camera and a validated method like Electrooculography (EOG) to establish ground truth [22].

- Annotation:

- Manually or semi-automatically label every frame in the validation dataset with the ground truth eye state ("open" or "closed").

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Run the EAR detection algorithm on the dataset.

- Compare the algorithm's output against the ground truth labels frame-by-frame.

- Calculate standard classification metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve [35] [38].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Facial Landmark Detector | Detects and localizes key facial points (eyes, nose, mouth) required for EAR calculation. | Dlib's 68-point predictor; Multi-task Cascaded Convolutional Networks (MTCNN). |

| Eye State Datasets | Provides standardized data for training and validating blink detection models. | MRL Eye Dataset [38]; TalkingFace Dataset [35]; NTHU-DDD [38]. |

| Computer Vision Library | Provides foundational algorithms for image processing, video I/O, and matrix operations. | OpenCV (Open Source Computer Vision Library). |

| Webcam / Infrared Camera | The hardware sensor for capturing video streams of the user's face. | Standard USB webcam (for visible light); IR-sensitive camera with IR illuminators (for dark conditions). |

| Video-Oculography (VOG) System | A high-accuracy, commercial reference system for validating blink parameters and eye movements. | Tobii Pro Spectrum/Fusion (provides eye openness signal) [22]; Smart Eye Pro. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Enables the development and deployment of advanced models for gaze and blink estimation. | TensorFlow, PyTorch; Pre-trained models like VGG19, ResNet, Vision Transformer (ViT) [37] [38]. |

System Integration and Workflow Visualization

The integration of EAR detection into a functional communication system involves a multi-stage pipeline. The workflow below illustrates the pathway from image acquisition to command execution, which is critical for building robust assistive devices.

Diagram 1: Real-Time Blink Detection and Command Workflow. This flowchart outlines the sequential process of capturing video, processing each frame to detect blinks using the Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR), and translating consecutive blinks into a functional command for communication.

The logic for classifying blinks and interpreting them into commands relies on a well-defined state machine. The following diagram details the decision-making process for categorizing blinks and managing the timing of a communication sequence.

Diagram 2: Blink Classification and Sequence Logic. This chart details the process of classifying a detected blink by its duration and managing the timing for concluding a command sequence, which is fundamental for protocols like Blink-To-Live [36].

Electroencephalography (EEG) provides a non-invasive method for detecting voluntary eye blinks, which is a critical capability for developing brain-computer interface (BCI) systems for patients with severe motor impairments. These systems enable communication by translating intentional blink patterns into control commands. The detection of blinks from EEG signals leverages the high-amplitude artifacts generated by the electrical activity of the orbicularis oculi muscle and the retinal dipole movement during eye closure [40] [9]. This document details the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for reliably identifying and classifying blink events from EEG data, with a specific focus on applications in assistive communication devices.

Physiological Basis of the EEG Blink Signal

The blink artifact observed in EEG recordings is a complex signal originating from both myogenic and ocular sources. Blinking involves the coordinated action of the levator palpebrae superioris and orbicularis oculi muscles [40]. This muscle activity generates electrical potentials that are readily detected by scalp electrodes. Furthermore, the eye itself acts as a corneal-retinal dipole, with movement during a blink causing a significant shift in the electric field, which is picked up by EEG electrodes [9].

The resulting blink artifact is characterized by a high-amplitude, sharp waveform, often exceeding 100 µV, which is substantially larger than the background cortical EEG activity [40]. This signal is most prominent over the frontal brain regions, particularly at electrodes Fp1, Fp2, Fz, F3, and F4, due to their proximity to the eyes [40]. The stereotypical morphology and high signal-to-noise ratio make blinks an excellent candidate for detection and classification in BCI systems.

Table 1: Key Electrode Locations for Blink Detection

| Electrode | Location | Sensitivity to Blinks |

|---|---|---|

| Fp1 | Left frontal pole, above the eye | Very High |

| Fp2 | Right frontal pole, above the eye | Very High |

| Fz | Midline frontal | High |

| F3 | Left frontal | Moderate to High |

| F4 | Right frontal | Moderate to High |

Detection Methodologies and Performance

Research has explored a wide spectrum of methodologies for blink detection, from traditional machine learning to advanced deep learning architectures. The choice of methodology often involves a trade-off between computational efficiency, required hardware complexity, and classification accuracy.

Hardware Configurations and Comparative Performance

Recent studies demonstrate that effective blink detection is achievable even with portable, low-density EEG systems, enhancing the practicality of BCI for everyday use.

Table 2: Comparison of Blink Detection Modalities and Performances

| Modality / Approach | Key Methodology | Reported Performance | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portable 2-Channel EEG [41] | 21 features + Machine Learning (Leave-one-subject-out) | Blinks: 95% acc.; Horizontal movements: 94% acc. | High portability, quick setup, comparable to multi-channel systems |

| 8-Channel Wearable EEG [42] | XGBoost, SVM, Neural Network | Multiple blinks classification: 89.0% accuracy | Classifies no-blink, single-blink, and consecutive two-blinks |

| 8-Channel Wearable EEG [42] | YOLO (You Only Look Once) model | Recall: 98.67%, Precision: 95.39%, mAP50: 99.5% | Superior for real-time detection of multiple blinks in a single timeframe |

| Wavelet + Autoencoder + k-NN [43] | Crow-Search Algorithm optimized k-NN | Accuracy: ~96% across datasets | Combines robust feature extraction with optimized traditional ML |

| Deep Learning (CNN-RNN) [40] | Hybrid Convolutional-Recurrent Neural Network | Healthy: 95.8% acc. (5 channels); PD: 75.8% acc. | Robust in clinical populations (e.g., Parkinson's disease) |

Signaling Pathway of the Blink Reflex

The following diagram illustrates the neural pathway involved in the blink reflex, which underlies the generation of the observable EEG signal.

Experimental Protocols for Blink Detection

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for setting up an experiment to acquire EEG signals for voluntary blink detection, based on standardized methodologies from recent literature.

Protocol: EEG Data Acquisition for Voluntary Blinks

Objective: To collect high-quality EEG data corresponding to predefined voluntary blink patterns for developing a BCI communication system.

Materials:

- EEG system (amplifier and cap, minimum 2 channels, 8+ recommended)

- Electrolyte gel or saline solution

- A computer with stimulus presentation software (e.g., PsychoPy, E-Prime, or custom MATLAB/Python script)

- Electrically shielded and quiet room

Procedure:

Participant Preparation:

- Obtain informed consent and explain the task.

- Fit the EEG cap, ensuring electrodes Fp1, Fp2, Fz, F3, and F4 are correctly positioned according to the 10-20 international system.

- Apply electrolyte gel to achieve electrode impedances below 10 kΩ, which is critical for obtaining a clean signal.

Experimental Task Design:

- Present visual or auditory cues on a computer screen to instruct the participant to perform specific blink actions. A sample trial structure is as follows [42]:

- Rest Period (3-5 seconds): A fixation cross is displayed. The participant is instructed to relax and avoid blinking.

- Cue Period (2 seconds): A text or symbol cue indicates the required blink pattern. Standard cues include:

- "Single Blink"

- "Double Blink" (two consecutive blinks)

- Execution Period (3 seconds): The participant performs the cued blink action.

- Repeat each trial type (e.g., no-blink, single-blink, double-blink) for a minimum of 30-50 repetitions to gather sufficient data for model training and validation. Randomize the trial order to prevent habituation.

- Present visual or auditory cues on a computer screen to instruct the participant to perform specific blink actions. A sample trial structure is as follows [42]:

Data Recording:

- Set the EEG amplifier to a sampling rate of at least 250 Hz (512 Hz is common) [40].

- Apply an online band-pass filter (e.g., 0.1 - 30 Hz) during acquisition to attenuate high-frequency noise and slow drifts [42].

- Record trigger signals from the stimulus presentation software synchronously with the EEG data to mark the onset of each cue and execution period.

Data Processing and Feature Extraction Workflow

The raw EEG data must be processed and transformed to extract meaningful features for blink classification. The following workflow is recommended.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Pre-processing:

- Filtering: Apply a zero-phase band-pass filter (e.g., 1-15 Hz) to isolate the frequency components most relevant to blinks and remove high-frequency muscle noise and slow drifts [42] [40].

- Segmentation: Segment the continuous EEG data into epochs (e.g., -0.5 to +3 seconds relative to the cue onset) for each trial.

Feature Extraction:

- Extract a suite of features from each EEG epoch to characterize the blink signal. The following features have proven effective [42] [43]:

- Time-Domain Features: Maximum amplitude, Root Mean Square (RMS), Signal Magnitude Area (SMA).

- Amplitude-Driven Features: Peak-to-peak amplitude, Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- Statistical Features: Mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis of the signal.

- Time-Frequency Features: Apply Wavelet Transform (e.g., using Morlet wavelets) to capture joint time-frequency information, which is highly effective for representing non-stationary blink signals [43].

- Extract a suite of features from each EEG epoch to characterize the blink signal. The following features have proven effective [42] [43]:

Model Training and Classification:

- Model Selection: For rapid prototyping, begin with traditional machine learning models like Crow-Search-Optimized k-NN [43] or Support Vector Machines (SVM) [42], which offer high performance with interpretable results.

- Deep Learning: For maximum accuracy, especially in complex classification tasks (e.g., single vs. double blinks), implement a hybrid CNN-RNN architecture [40] or the YOLO model [42].

- Validation: Use leave-one-subject-out (LOSO) cross-validation to rigorously evaluate model generalizability to new, unseen users [41].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for EEG Blink Detection

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-channel EEG System | Recording electrical brain activity. | BioSemi Active II, Ultracortex "Mark IV" headset [42] [44]. A portable 2-channel system can be sufficient [41]. |

| Electrolyte Gel | Ensuring high-conductivity, low-impedance connection between scalp and electrodes. | Standard EEG conductive gels. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Delivering precise visual/auditory cues to guide voluntary blink tasks. | PsychoPy, E-Prime, MATLAB, Python. |

| Signal Processing Toolboxes | Pre-processing, feature extraction, and model implementation. | EEGLAB, MNE-Python, BLINKER toolbox [44]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Building and training blink classification models. | Scikit-learn (for SVM, k-NN), XGBoost, PyTorch/TensorFlow (for CNN, RNN, YOLO) [42] [43] [40]. |

Electrooculography (EOG) leverages the corneo-retinal standing potential inherent in the human eye to detect and record eye movements and blinks. This potential, which exists between the positively charged cornea and the negatively charged retina, acts as a biological dipole. When the eye rotates, this dipole moves relative to electrodes placed on the skin around the orbit, producing a measurable change in voltage [45]. Blinks, characterized by a rapid, simultaneous movement of both eyelids, induce a distinctive high-amplitude signal due to the upward and inward rotation of the globe (Bell's phenomenon). This technical note details the application of EOG within a research framework focused on developing a voluntary blink-controlled communication protocol for patients with severe motor disabilities, such as those in advanced stages of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) or Locked-In Syndrome (LIS). The non-invasive nature and relatively simple setup of EOG make it a viable tool for creating assistive technologies that rely on intentional, voluntary blinks as a binary or coded control signal.

Key Principles and Quantitative Blink Data

A comprehensive understanding of blink characteristics is fundamental to designing robust detection algorithms. Blinks are categorized into three types: voluntary (intentional), reflexive (triggered by external stimuli), and spontaneous (unconscious). For communication protocols, the reliable identification of voluntary blinks is paramount. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics for spontaneous blinks, which serve as a baseline for distinguishing intentional blinks, derived from eye-tracking studies [45].

Table 1: Quantitative Characteristics of Spontaneous Blinks in Healthy and Clinical Populations

| Characteristic | Healthy Adults (Baseline) | Parkinson's Disease (PD) Patients | Notes and Correlations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blink Rate (BR) | 15-20 blinks/minute | Significantly reduced | In PD, BR is negatively correlated with motor deficit severity and dopamine depletion [45]. |

| Blink Duration (BD) | 100-400 milliseconds | Significantly increased | In PD, increased BD is linked to non-motor symptoms like sleepiness rather than motor severity [45]. |

| Blink Waveform Amplitude | 50-200 µV (EOG) | Not specifically quantified in search results | Amplitude is highly dependent on electrode placement and individual physiological differences. |

| Synchrony | Tendency to synchronize blinking with observed social cues [46] | Not reported | This synchrony is attenuated in adults with ADHD symptoms, linked to dopaminergic and noradrenergic dysfunction [46]. |

Experimental Protocol: EOG Setup and Blink Detection for Communication Paradigms

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for establishing an EOG system to acquire corneo-retinal potentials for the purpose of voluntary blink detection.

Research Reagent and Equipment Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for EOG-based Blink Detection Research

| Item | Function/Explanation | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Disposable Ag/AgCl Electrodes | To ensure stable, low-impedance electrical contact with the skin for high-quality signal acquisition. | Pre-gelled, foam-backed, 10 mm diameter. |

| Biopotential Amplifier & Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | To amplify the microvolt-level EOG signal and convert it to digital data for processing. | Input impedance >100 MΩ, Gain: 1000-5000, Bandpass Filter: 0.1-30 Hz. |

| Electrode Lead Wires | To connect the skin electrodes to the amplifier. | Shielded cables to reduce 50/60 Hz power line interference. |

| Skin Prep Kit (Alcohol wipes, Abrasive gel) | To clean and reduce dead skin cells, thereby lowering skin impedance for a clearer signal. | 70% Isopropyl Alcohol wipes, mild skin preparation gel. |

| Electrode Adapters/Strap | To secure electrodes in place around the eye orbit. | Headbands or specialized adhesive rings. |

| Signal Processing Software | To implement real-time or offline blink detection algorithms (thresholding, template matching). | MATLAB, Python (with libraries like SciPy and NumPy), or LabVIEW. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Participant Preparation and Electrode Placement:

- Inform the participant about the procedure and obtain consent. Ensure they are seated comfortably.

- Clean the skin areas around both eyes with an alcohol wipe and allow to dry.

- Apply five electrodes per eye for robust differential measurement:

- Right Outer Canthus (ROC): ~1 cm lateral to the right eye's outer corner.

- Left Outer Canthus (LOC): ~1 cm lateral to the left eye's outer corner.

- Above Right Eye (Supraorbital): ~2 cm above the eyebrow on the forehead.

- Below Right Eye (Infraorbital): ~2 cm below the lower eyelid.

- Reference (Ground): On the center of the forehead or mastoid bone.

- Connect the lead wires to the corresponding electrodes.

System Calibration and Signal Acquisition:

- Connect the leads to the biopotential amplifier and DAQ system.

- Instruct the participant to look straight ahead at a fixed point to establish a baseline.

- Perform a calibration routine: Ask the participant to look sequentially at targets (e.g., left, right, up) to map E signal voltage to eye position.

- Initiate data recording. The vertical EOG channel (difference between supraorbital and infraorbital electrodes) will be the primary source for blink detection.

Blink Detection Algorithm (Offline/Real-time):

- Bandpass Filter: Apply a digital bandpass filter (e.g., 0.1-15 Hz) to the raw EOG signal to remove slow drifts and high-frequency noise.

- Threshold Detection: Calculate the signal's moving average and standard deviation. Define a blink event when the signal amplitude exceeds a set threshold (e.g., 4-5 times the standard deviation above the baseline).

- Morphological Check: Implement checks based on blink duration (e.g., 100-500 ms) to distinguish true blinks from noise spikes or saccades.

- Voluntary Blink Identification: For communication protocols, use timing patterns (e.g., a double blink within a specific time window) or count-based sequences (e.g., three blinks for "yes") to decode intentional commands from spontaneous blinks.

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for a blink-controlled communication system and the underlying neurophysiological pathway.

Experimental Workflow for Blink-Controlled Communication

Neurophysiological Pathway of a Voluntary Blink

Discussion and Application in Patient Research

The primary application of this protocol is the development of a voluntary blink-controlled communication system. Such a system translates specific blink patterns into commands, enabling patients to spell words, select pre-defined phrases, or control their environment. The reliability of this system hinges on accurately differentiating voluntary blinks from spontaneous and reflexive ones, a task that can be improved by analyzing the subtle differences in their duration and waveform morphology [45].

Furthermore, the EOG signal itself may offer insights beyond mere command detection. As blink rate and duration are modulated by central dopamine levels [45] [46], longitudinal EOG recording could potentially serve as a non-invasive biomarker for tracking disease progression or therapeutic efficacy in neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease within clinical trial settings. The documented attenuation of blink synchrony as a social cue in conditions like ADHD [46] further underscores the potential of EOG to probe the integrity of neural circuits underlying social cognition, opening avenues for research in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Voluntary blink-controlled communication protocols represent a critical advancement in the field of assistive technology, enabling individuals with severe motor impairments, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or paralysis, to communicate through intentional eye movements [23]. These systems function by translating specific blink patterns into discrete commands, forming a complete encoding scheme from simple alerts to complex character-based communication similar to Morse code. The fundamental premise involves using blink duration, count, and laterality (unilateral or bilateral) as the basic encoding units for information transmission. This approach leverages the fact that eye movements often remain functional even when most other voluntary muscles are paralyzed, making blink-based systems particularly valuable for patients who have lost other means of communication [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Blink Detection System Design

Research into blink-controlled interfaces has employed various detection methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations [23]:

- Pressure Sensor Systems: Thin-film pressure sensors capture delicate surface muscle pressure alterations around the ocular region. This approach provides excellent temporal synchronization, avoids the need for conductive gels, and maintains stable operation under various environmental conditions without being affected by illumination, noise, or electromagnetic interference [23].

- Computer Vision Methods: These systems use camera-based tracking of eye movements and blink gestures. While inexpensive and obtainable, they involve complex image processing algorithms, require significant computational power, restrict head movements, and are sensitive to environmental lighting conditions [23].

- Bioelectrical Signal Detection: Surface electromyography (sEMG) electrodes capture electrical signals from muscles involved in blinking. Though offering good temporal resolution, these signals are sensitive to interference and typically require conductive gels that cause discomfort during prolonged use [23].

- Infrared-Based Methods: These systems provide higher recognition accuracy but are highly susceptible to light interference and potentially pose risks with prolonged eye exposure to infrared radiation [23].

Table: Comparison of Blink Detection Methodologies

| Method | Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|